#asimov

“Fantastic Voyage” (1966).

The film was good, but Isaac Asimov’s novelization was even better.

Post link

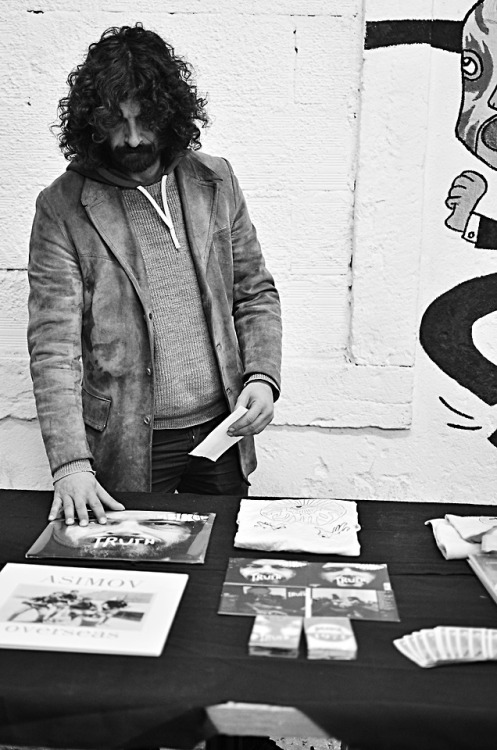

Isaac Asimov (signed prints)© Iván García

Pencils, markers and digital.

Signed prints, martelec paper 240 gr.

3 Sizes:

- 148 x 210 mm (A5)

- 297x210 mm (A4)

- 420x297 mm (A3)

Now you can get all my prints at https://www.etsy.com/shop/IvanGshop

or message me

My sitessite-etsy-facebook-tumblr-instagram

Post link

By Isaac Asimov

The Skeptical Inquirer, Fall 1989, Vol. 14, No. 1, Pp. 35-44

I RECEIVED a letter the other day. It was handwritten in crabbed penmanship so that it was very difficult to read. Nevertheless, I tried to make it out just in case it might prove to be important. In the first sentence, the writer told me he was majoring in English literature, but felt he needed to teach me science. (I sighed a bit, for I knew very few English Lit majors who are equipped to teach me science, but I am very aware of the vast state of my ignorance and I am prepared to learn as much as I can from anyone, so I read on.)

It seemed that in one of my innumerable essays, I had expressed a certain gladness at living in a century in which we finally got the basis of the universe straight.

I didn’t go into detail in the matter, but what I meant was that we now know the basic rules governing the universe, together with the gravitational interrelationships of its gross components, as shown in the theory of relativity worked out between 1905 and 1916. We also know the basic rules governing the subatomic particles and their interrelationships, since these are very neatly described by the quantum theory worked out between 1900 and 1930. What’s more, we have found that the galaxies and clusters of galaxies are the basic units of the physical universe, as discovered between 1920 and 1930.

These are all twentieth-century discoveries, you see.

The young specialist in English Lit, having quoted me, went on to lecture me severely on the fact that in every century people have thought they understood the universe at last, and in every century they were proved to be wrong. It follows that the one thing we can say about our modern “knowledge” is that it is wrong. The young man then quoted with approval what Socrates had said on learning that the Delphic oracle had proclaimed him the wisest man in Greece. “If I am the wisest man,” said Socrates, “it is because I alone know that I know nothing.” the implication was that I was very foolish because I was under the impression I knew a great deal.

My answer to him was, “John, when people thought the earth was flat, they were wrong. When people thought the earth was spherical, they were wrong. But if you think that thinking the earth is spherical is just as wrong as thinking the earth is flat, then your view is wronger than both of them put together.”

The basic trouble, you see, is that people think that “right” and “wrong” are absolute; that everything that isn’t perfectly and completely right is totally and equally wrong.

However, I don’t think that’s so. It seems to me that right and wrong are fuzzy concepts, and I will devote this essay to an explanation of why I think so.

When my friend the English literature expert tells me that in every century scientists think they have worked out the universe and are always wrong, what I want to know is how wrong are they? Are they always wrong to the same degree? Let’s take an example.

In the early days of civilization, the general feeling was that the earth was flat. This was not because people were stupid, or because they were intent on believing silly things. They felt it was flat on the basis of sound evidence. It was not just a matter of “That’s how it looks,” because the earth does not look flat. It looks chaotically bumpy, with hills, valleys, ravines, cliffs, and so on.

Of course there are plains where, over limited areas, the earth’s surface does look fairly flat. One of those plains is in the Tigris-Euphrates area, where the first historical civilization (one with writing) developed, that of the Sumerians.

Perhaps it was the appearance of the plain that persuaded the clever Sumerians to accept the generalization that the earth was flat; that if you somehow evened out all the elevations and depressions, you would be left with flatness. Contributing to the notion may have been the fact that stretches of water (ponds and lakes) looked pretty flat on quiet days.

Another way of looking at it is to ask what is the “curvature” of the earth’s surface Over a considerable length, how much does the surface deviate (on the average) from perfect flatness. The flat-earth theory would make it seem that the surface doesn’t deviate from flatness at all, that its curvature is 0 to the mile.

Nowadays, of course, we are taught that the flat-earth theory is wrong; that it is all wrong, terribly wrong, absolutely. But it isn’t. The curvature of the earth is nearly 0 per mile, so that although the flat-earth theory is wrong, it happens to be nearly right. That’s why the theory lasted so long.

There were reasons, to be sure, to find the flat-earth theory unsatisfactory and, about 350 B.C., the Greek philosopher Aristotle summarized them. First, certain stars disappeared beyond the Southern Hemisphere as one traveled north, and beyond the Northern Hemisphere as one traveled south. Second, the earth’s shadow on the moon during a lunar eclipse was always the arc of a circle. Third, here on the earth itself, ships disappeared beyond the horizon hull-first in whatever direction they were traveling.

All three observations could not be reasonably explained if the earth’s surface were flat, but could be explained by assuming the earth to be a sphere.

What’s more, Aristotle believed that all solid matter tended to move toward a common center, and if solid matter did this, it would end up as a sphere. A given volume of matter is, on the average, closer to a common center if it is a sphere than if it is any other shape whatever.

About a century after Aristotle, the Greek philosopher Eratosthenes noted that the sun cast a shadow of different lengths at different latitudes (all the shadows would be the same length if the earth’s surface were flat). From the difference in shadow length, he calculated the size of the earthly sphere and it turned out to be 25,000 miles in circumference.

The curvature of such a sphere is about 0.000126 per mile, a quantity very close to 0 per mile, as you can see, and one not easily measured by the techniques at the disposal of the ancients. The tiny difference between 0 and 0.000126 accounts for the fact that it took so long to pass from the flat earth to the spherical earth.

Mind you, even a tiny difference, such as that between 0 and 0.000126, can be extremely important. That difference mounts up. The earth cannot be mapped over large areas with any accuracy at all if the difference isn’t taken into account and if the earth isn’t considered a sphere rather than a flat surface. Long ocean voyages can’t be undertaken with any reasonable way of locating one’s own position in the ocean unless the earth is considered spherical rather than flat.

Furthermore, the flat earth presupposes the possibility of an infinite earth, or of the existence of an “end” to the surface. The spherical earth, however, postulates an earth that is both endless and yet finite, and it is the latter postulate that is consistent with all later findings.

So, although the flat-earth theory is only slightly wrong and is a credit to its inventors, all things considered, it is wrong enough to be discarded in favor of the spherical-earth theory.

And yet is the earth a sphere?

No, it is not a sphere; not in the strict mathematical sense. A sphere has certain mathematical properties - for instance, all diameters (that is, all straight lines that pass from one point on its surface, through the center, to another point on its surface) have the same length.

That, however, is not true of the earth. Various diameters of the earth differ in length.

What gave people the notion the earth wasn’t a true sphere? To begin with, the sun and the moon have outlines that are perfect circles within the limits of measurement in the early days of the telescope. This is consistent with the supposition that the sun and the moon are perfectly spherical in shape.

However, when Jupiter and Saturn were observed by the first telescopic observers, it became quickly apparent that the outlines of those planets were not circles, but distinct ellipses. That meant that Jupiter and Saturn were not true spheres.

Isaac Newton, toward the end of the seventeenth century, showed that a massive body would form a sphere under the pull of gravitational forces (exactly as Aristotle had argued), but only if it were not rotating. If it were rotating, a centrifugal effect would be set up that would lift the body’s substance against gravity, and this effect would be greater the closer to the equator you progressed. The effect would also be greater the more rapidly a spherical object rotated, and Jupiter and Saturn rotated very rapidly indeed.

The earth rotated much more slowly than Jupiter or Saturn so the effect should be smaller, but it should still be there. Actual measurements of the curvature of the earth were carried out in the eighteenth century and Newton was proved correct.

The earth has an equatorial bulge, in other words. It is flattened at the poles. It is an “oblate spheroid” rather than a sphere. This means that the various diameters of the earth differ in length. The longest diameters are any of those that stretch from one point on the equator to an opposite point on the equator. This “equatorial diameter” is 12,755 kilometers (7,927 miles). The shortest diameter is from the North Pole to the South Pole and this “polar diameter” is 12,711 kilometers (7,900 miles).

The difference between the longest and shortest diameters is 44 kilometers (27 miles), and that means that the “oblateness” of the earth (its departure from true sphericity) is 44/12755, or 0.0034. This amounts to l/3 of 1 percent.

To put it another way, on a flat surface, curvature is 0 per mile everywhere. On the earth’s spherical surface, curvature is 0.000126 per mile everywhere (or 8 inches per mile). On the earth’s oblate spheroidal surface, the curvature varies from 7.973 inches to the mile to 8.027 inches to the mile.

The correction in going from spherical to oblate spheroidal is much smaller than going from flat to spherical. Therefore, although the notion of the earth as a sphere is wrong, strictly speaking, it is not as wrong as the notion of the earth as flat.

Even the oblate-spheroidal notion of the earth is wrong, strictly speaking. In 1958, when the satellite Vanguard I was put into orbit about the earth, it was able to measure the local gravitational pull of the earth–and therefore its shape–with unprecedented precision. It turned out that the equatorial bulge south of the equator was slightly bulgier than the bulge north of the equator, and that the South Pole sea level was slightly nearer the center of the earth than the North Pole sea level was.

There seemed no other way of describing this than by saying the earth was pear-shaped, and at once many people decided that the earth was nothing like a sphere but was shaped like a Bartlett pear dangling in space. Actually, the pear-like deviation from oblate-spheroid perfect was a matter of yards rather than miles, and the adjustment of curvature was in the millionths of an inch per mile.

In short, my English Lit friend, living in a mental world of absolute rights and wrongs, may be imagining that because all theories are wrong, the earth may be thought spherical now, but cubical next century, and a hollow icosahedron the next, and a doughnut shape the one after.

What actually happens is that once scientists get hold of a good concept they gradually refine and extend it with greater and greater subtlety as their instruments of measurement improve. Theories are not so much wrong as incomplete.

This can be pointed out in many cases other than just the shape of the earth. Even when a new theory seems to represent a revolution, it usually arises out of small refinements. If something more than a small refinement were needed, then the old theory would never have endured.

Copernicus switched from an earth-centered planetary system to a sun-centered one. In doing so, he switched from something that was obvious to something that was apparently ridiculous. However, it was a matter of finding better ways of calculating the motion of the planets in the sky, and eventually the geocentric theory was just left behind. It was precisely because the old theory gave results that were fairly good by the measurement standards of the time that kept it in being so long.

Again, it is because the geological formations of the earth change so slowly and the living things upon it evolve so slowly that it seemed reasonable at first to suppose that there was no change and that the earth and life always existed as they do today. If that were so, it would make no difference whether the earth and life were billions of years old or thousands. Thousands were easier to grasp.

But when careful observation showed that the earth and life were changing at a rate that was very tiny but not zero, then it became clear that the earth and life had to be very old. Modern geology came into being, and so did the notion of biological evolution.

If the rate of change were more rapid, geology and evolution would have reached their modern state in ancient times. It is only because the difference between the rate of change in a static universe and the rate of change in an evolutionary one is that between zero and very nearly zero that the creationists can continue propagating their folly.

Since the refinements in theory grow smaller and smaller, even quite ancient theories must have been sufficiently right to allow advances to be made; advances that were not wiped out by subsequent refinements.

The Greeks introduced the notion of latitude and longitude, for instance, and made reasonable maps of the Mediterranean basin even without taking sphericity into account, and we still use latitude and longitude today.

The Sumerians were probably the first to establish the principle that planetary movements in the sky exhibit regularity and can be predicted, and they proceeded to work out ways of doing so even though they assumed the earth to be the center of the universe. Their measurements have been enormously refined but the principle remains.

Naturally, the theories we now have might be considered wrong in the simplistic sense of my English Lit correspondent, but in a much truer and subtler sense, they need only be considered incomplete.

Taken from: http://chem.tufts.edu/answersinscience/relativityofwrong.htm

We get enough people at book fairs, sellers included, asking us what Speculative Fiction is that we thought an explanation was merited.

Note: I have no intention of arguing the case that science fiction and fantasy are as much skilled works of art as regular literature; that argument has been covered enough times and it bores me. Time determines what is art not genre.

As the term suggests speculative fiction is fiction that involves some element of speculation. Of course, one can argue that all fiction is speculative insofar as it speculates what could happen if various elements of a story were combined. Yet we feel that this term is descriptive enough to encompass the type of literature we want to categorise. First, a word about genre

Book genre is of limited use and is often more harmful than good. If you went into a bookshop and asked for literature, you’d be taken to the fiction section. If you said that you were looking for any Darwinian literature you’d be sent to the science section. At some point it was determined that literature suggested artistic merit. Yet we also use it to cover a particular grouping of written works. The point is that classifying the written word is a little futile as common usage will usually dictate what that classification envelops, and common usage is of course open to interpretation. Genre does however allow boundaries to be set for marketing purposes; if a reader enjoyed a number of books in a certain genre then there’s a reasonable chance they’d enjoy other books in the same genre. From a critical perspective, understanding genre helps align a work of literature with one’s expectations; certain tropes and mechanisms are, to some extent, more acceptable in one genre than another.

Now, this element of speculation. The speculation in speculative fiction isn’t concerned solely with speculation over how various story elements might interact, but speculation over the fabric of those elements. A work of speculative fiction takes one or more elements of an otherwise perfectly possible story and speculates as to what would happen if that element existed outside of current understanding or experience. Essentially, it’s writing about things that aren’t currently possible. The Road by Cormac McCarthy is a father-son story of survival, nearly everything is contemporaneously possible, except one thing the setting of the story is plausible future.

When you pick up an Agatha Christie, a Jane Austen or a Graham Greene, regardless of how the story unfurls, and how perhaps unlikely the story, it’s always within the realm of possibility (poor writing and deus ex machina aside). Yet a Philip K. Dick, a Tolkien or a Stephen King will always seem impossible, given current understanding.

The word current is key, to allow inclusion of scientific speculation. A seminal work like Kim Stanley Robinson’s Red Mars has a lot of the science in place to explain how the colonisation of Mars might / could take place (I assume the science is correct; it doesn’t matter to me personally but I know a lot of readers are particular in this area). The speculation is on how plausible, but currently theoretical, scientific and technological advances might solve a problem.

There is a slight grey area where such scientific knowledge and its technical implementation exists and is currently possible and a good story has been written about it. Imagine a book about travelling to the moon written in 1969. Imagine it’s not an adventure, it explores personal relationships between the characters and their heroic journey. For someone unfamiliar with planned space travel such a book would seem like science fiction, yet it was of course entirely possible in 1969. I personally wouldn’t classify such a work as speculative fiction as it doesn’t fit the definition, but I’d certainly class it as science fiction if I were to market it as it would fit the bill for many readers. Similarly a book like Psycho, it’s a work of horror but there’s no supernatural element and it’s plausible and possible given current understanding.

For books like The Hobbit orCarriethecurrent part of the definition becomes less important; Middle-Earth neither has nor probably will exist, neither will telekinesis. Of course, as science progresses some things that are currently implausible will be come plausible, if not possible. Space travel being a great example; progress is constantly being made.

Speculative fiction is also an umbrella term so includes the majority of works in the fantasy, science fiction and horror genres, also smaller genres such as magic realism, weird fiction and more classical genres such as mythology, fairy tales and folklore. Many people break speculative fiction into two categories though: fantasy and science fiction, the former being implausible the latter being plausible (in simplistic terms). This is helpful for those interested in having some sort of technical foundation upon which to build their speculation, and those who aren’t.

When one thinks of science fiction, one thinks back to the 1930’s and the Gernsback era, perhaps earlier to Wells and Verne. One might even cite Frankenstein. When one thinks of fantasy one thinks of Tolkien, perhaps Victorian / Edwardian ghost stories, Dracula, perhaps Frankenstein. It seems comfortable to think of these things as modern endeavours. Anything earlier often falls under the general category of literature (in the non-speculative fiction sense). Take More’s Utopia,you’d find that under literature or classics, not under fantasy. Similarly Gulliver’s Travels. Again, this is just marketing; there’s no reason why Gulliver’s Travels should not be shelved next to Lord of the Rings other than to meet a reader’s expectation.

At Hyraxia Books we like to think of certain classic works not simply as works that have contributed to the literary canon, but also as works that have contributed to the speculative fiction canon. For us, Aesop’s Fables,Paradise Lost, The Divine Comedy, Otranto, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Iliad, The Prose Edda, Beowulf and the Epic of Gilgamesh are not simply classics, but also speculative fiction classics. We don’t like to think of the genre starting in the last two hundred years, we like to think of literature (in the non-speculative fiction sense) having branched off from the speculative rather than the other way round. We like to see how that story has played out over the millennia.

That is how we define speculative fiction for the basis of our stock. Of course, we stock other items too, many of which we are very fond of.

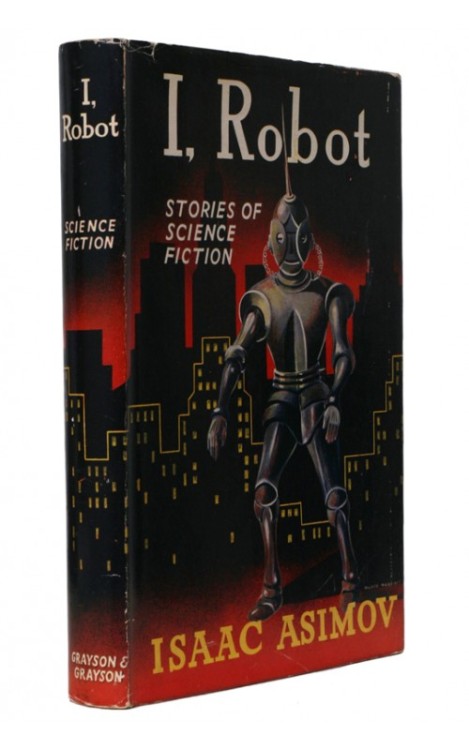

Isaac Asimov - I, Robot - Grayson and Grayson, 1952, UK First Edition

London, Grayson & Grayson, 1952. Hardback first edition and first impression. The book and jacket are near fine. Owner’s stamp to front end paper, owner’s plate to title page (covering owner’s stamp). Some soiling to page edges. Jacket is near fine also with a couple of neat closed tears, and a few creases. A very nice copy.

Post link

why cant i be normal whenever i see a handsome man im never like “wow good looking dude” im immediately like “wow this is exactly like when daneel olivaw”

yeah well this is what happens when you tell someone that Fox owns the rights to your identity Goyer

we need more foundation ads with demerzel for season 2, i want to be confronted with her incessantly i want everyone to have to deal with her

Hummin: I don’t suppose you saw Demerzel?

Hari: Who’s Demerzel?

Hummin: I saw Demerzel at a grocery store in the Imperial District yesterday. I told him how cool it was to meet him in person, but I didn’t want to be a douche and bother him and ask him for photos or anything. He said, “Oh, like you’re doing now?”

I was taken aback, and all I could say was “Huh?” but he kept cutting me off and going “huh? huh? huh?” and closing his hand shut in front of my face. I walked away and continued with my shopping, and I heard him chuckle as I walked off. When I came to pay for my stuff up front I saw him trying to walk out the doors with like fifteen Milky Ways in his hands without paying.

The girl at the counter was very nice about it and professional, and was like “Sir, you need to pay for those first.” At first he kept pretending to be tired and not hear her, but eventually turned back around and brought them to the counter.

When she took one of the bars and started scanning it multiple times, he stopped her and told her to scan them each individually “to prevent any electrical infetterence,” and then turned around and winked at me. I don’t even think that’s a word. After she scanned each bar and put them in a bag and started to say the price, he kept interrupting her by yawning really loudly.

Laura Birn + Foundation shirt

more hot daneel olivaws please

Laura Birn’s Demerzel Daneeling Absolute Olivaw

Bonus Kurosuke (which is canon imo)

reminder that daneel/demerzel based the design of the Imperial Palace off of Aurora ❤️

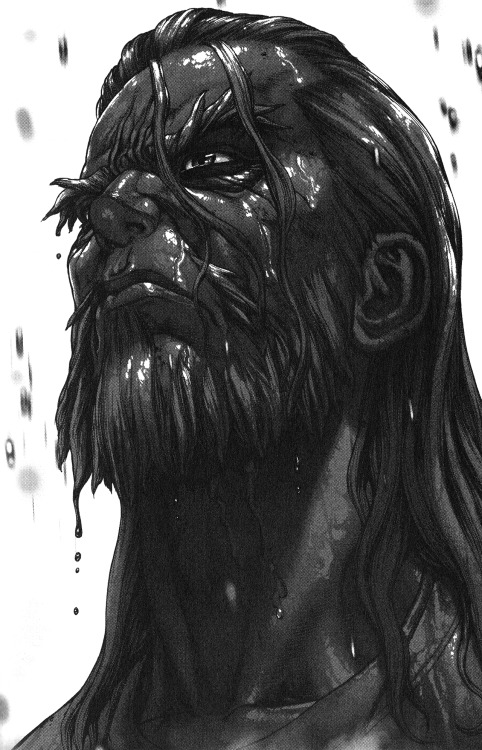

*We are the robots playing in the background* Art inspired by Asimov’s “The Positronic Man”

Post link

I am very proud of how page 50 came out. UwU

I wanted to have a big action shot of Gunvolt and Asimov fighting, and also wanted to include Copen and Gunvolt speaking over it. I wasn’t…totally sure how to break the page down as far as panels went, but then I decided to try out a series of much smaller panels with close-ups of Copen and Gunvolt’s faces, and I really like how it looks.

The curvy, question mark-shaped arc of the speech bubbles pleases me. :T

Post link

I was reviewing earlier pages to examine the way I drew flashback scenes in the early parts of the comic, and learned two things:

1) I actually had flashbacks confined to panels originally, and did not stick them inside of nebulous panel spaces made of dark color.

2) I…already had Gunvolt summarize what happened between him, Joule, and Asimov in their backstory, making this page redundant and forcing me to rewrite some dialogue to compensate for it. :T

ANYWAY, THIS PAGE IS ON TWITTERRRRRRR

Post link