#japanese prints

“Miyagino the filial”, (1847/1848 ?), Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861)

Print from the series “Stories of dutifulness and loyalty in revenge”.

Depicts one of the two sisters who avenged their father during the 17th century. Their story inspired the kabuki play “Go Taiheiki shiraishi banashi” for instance.

Here the older sister, Miyagino, is represented carrying both a naginata and a sake cup.

Post link

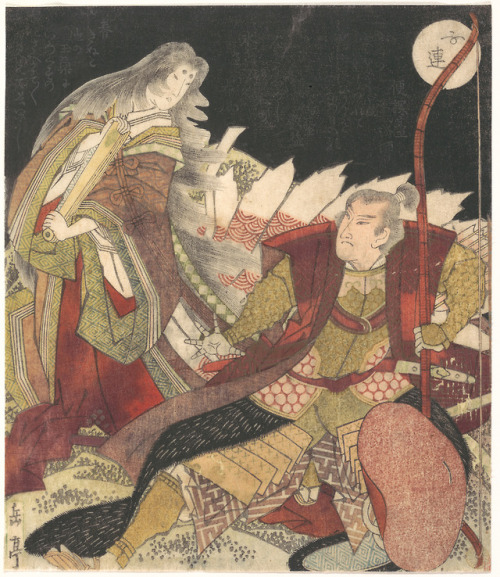

“Kiyoshi Hikariin” (1876), Toyohara Kunichika (1835-1900)

Print from the series “Thirty-six Good and Evil Beauties”

The princess Kiyoshi Hikariin draws her sword in order to avenge herself. The folding screen behind her is decorated with the mon (crest) of the powerful Tokugawa family, who ruled the shogunate during the Edo period.

Post link

Panchromatica Designs

Panchromatica Designs - reproductions of vintage illustrations available at wholesale prices

As I said in my last post, I used to have an online business on Etsy, known as Panchromatica Designs, selling reproductions of vintage illustrations. At its peak, I had about 600 items in that shop.

These included :

maps, theatre posters, Japanese prints, photographs, ocean liner postcards, propaganda posters, comic books, architectural illustrations, fashion plates and, a huge variety of other…

Today’s piece of gender non-conforming art history comes to us from 1790 Edo era Japan and features an onnagata, a word which loosely translates into “female impersonator [of the kabuki stage]”. (1) Onnagata became a theatrical staple once a law was passed mandating the exclusion of female actors in 1629. (2) Given the need for female characters to tell stories reflecting daily life, onnagata roles became wide spread. Given the sheer numbers, it is difficult to infer anything about the actors who portrayed these roles, but as some actors who specialized in onnagata roles chose to live as women off the stage, as well, (2, p. 28) these roles would likely have been pursued by people who, today, would be regarded as transgender women in the West.

Kabuki theater was originated in 1603 with all female troupes where, inversely, female actors played the male roles. (3) In 1629, the government banned women from the stage in an attempt to stem the widespread practice of their being available for sex work after the show. (3) The actresses were then replaced by wakashu (3) who were young men in their teens or early twenties and had not yet had their coming of age ceremony into adulthood. (4) The wakashu played both characters who were, themselves, wakashu, as well as female roles as onnagata, however, in 1642, the government banned both wakashu and onnagata parts because of the continued practice of the actors being available for sex work after the show. (3)

The government lifted the ban on wakashu theatrical characters in 1644 (as otherwise, during the ban, plays could only depict stories between adult males) and they lifted the ban on onnagata characters in 1652, however, in both cases it was with the caveat that the actors now had to shave the tops of their heads in the same manner that adult men were required to do. (3) The onnagata and theater wakashu then took up the practice of wearing head scarves to cover the shaven bald spot, as can be seen in this image. (3) Onnagata can be identified in art by their head scarves in combination with female hair styles which can be distinguished by the large comb running side to side across the top of the head.

This print is by Ryukosai Jokei from a book of prints entitled “Garden Puddles” and depicts the onnagata actor Nakamura Tomijuro standing in a garden under a blossoming cherry tree. (2, p. 34) Beginning in 1751, nigao-e, which were commercially available paintings or prints of popular actors, became widely available and very popular making Japan the first known place to develop a modern pop culture. Prior to nigao-e prints, which were made both for artistic purposes as well as for commercial advertisement, such art featured general stylized depictions of well known kabuki characters without attempting to portray the individual actors playing the roles. (2, p.34)

For this reason, onnagata in this era were frequently artistically depicted as idealized versions of cisgender women, though the public would have understood that they were onnagata performers, (2, p. 34) both because of their signature head scarves, but also because women were not allowed on the stage. (3) As a part of the trend of depicting individual actors rather than generic renditions of familiar characters, Ryukosai Jokei is thought to be the first artist to portray onnagata explicitly as assigned male actors playing female roles rather than as cisgender women as can be seen in the facial features in this illustration. (2, p. 34)

IMAGE SOURCE: Royal Ontario Museum

REFERENCES / FURTHER READING

(1) WIKIPEDIA ARTICLE: “Onnagata”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Onnagata

(2) Mostow, Joshua S. and Asato Ikeda. A Third Gender: Beautiful Youths in Japanese Edo-Period Prints and Paintings (1600-1868). Ontario: Royal Ontario Museum, 2016. Print.

(3) WIKIPEDIA ARTICLE: “Kabuki”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kabuki

(4) WIKIPEDIA ARTICLE: “Wakashu”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wakashū

WIKIPEDIA ARTICLE: “Kagema”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kagema

ISSENDAI ARTICLE: “Kaumro”

www.issendai.com/japanese-courtesans/kamuro.html

HYPERALLERGIC ARTICLE: “The Hidden History of Wakashu,; Edo Era Japan’s “Third Gender”

https://hyperallergic.com/367604/the-hidden-history-of-wakashu-edo-era-japans-third-gender/

Post link