#london history

FREE BOOK

yeah I saidFREE BOOK!!

Black London: Life Before Emancipation by Gretchen Gerzina (1995)

A glimpse into the lives of the thousands of Africans living in eighteenth century London.

more FREE BOOKS from lascasbookshelf.tumblr.com

||| Publisher’s Blurb|||

Gerzina has written a fascinating account of London blacks, focusing on the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Because of a paucity of sources from blacks themselves, Gerzina had to rely primarily on glimpses through white eyes, especially those of antislavery advocate Granville Sharp. Gerzina is quite adept at culling evidence of a rich, complex black life, with significant interaction (and intermarriage) with the white community.

more from Rutger’s University Press

Illustrations

Acknowledgements

1. Paupers and Princes: Repainting the Picture of Eighteenth-Century England

2. High Life below Stairs

3. What about Women?

4. Sharp and Mansfield: Slavery in the Courts

5. The Black Poor

6. The End of English Slavery

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Post link

FREE BOOK!

Ship and a Prayer: The Black Presence in Hammersmith and Fulham

Ethnic Communities Oral History Project, 1999

more FREE BOOKS from lascasbookshelf.tumblr.com

||| Publisher’s Blurb|||

Black people have been living and working in Britain since the 1550s. After the Second World War, mass migration from the Caribbean helped build the multi-cultural Britain we know today. This publication has been produced to celebrate the presence of the Black community in Hammersmith and Fulham over the past 100 years and the 50th anniversary of the arrival of the Empire Windrush. It is supported and funded by the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham. Its publication also commemorates the tenth anniversary of the Ethnic Communities Oral History Project’s (ECOHP) first African Caribbean publication, The Motherland Calls, in 1989. A Ship and a Prayer draws on interviews published by ECOHP during the past ten years.

Among the interviewees featured in A Ship and a Prayer are Randolph Beresford, a former Mayor of Hammersmith and Fulham who was made an MBE; Esther Bruce, whose autobiography received the Raymond Williams Prize for Community Publishing; and Connie Mark, who was awarded the British Empire Medal.

|||Contents|||

Before World War Two: Black Edwardians in Hammersmith and Fulham

The War Years (1939 - 45)

Empire Windrush

After Windrush

A Second Generation Perspective

Post link

A poster from the Underground Electric Railway Company in 1924. This particularly colourful poster illustrated the wide variety of contemporary London fashions at the time.

Post link

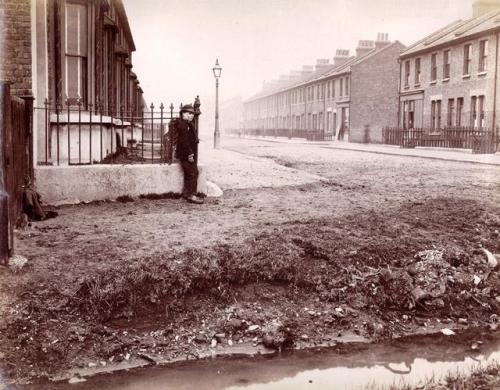

Navigators or “Navvies” building the London Underground in the late 1800’s - early 1900’s. Navvies were cheap labourers and mostly miners from Cornwall, or farmers from Scotland and Ireland. They were willing to go wherever there was work and found steady work with railway companies across Britain. Building the Underground was a long and dangerous process. There were many serious injuries and deaths during construction, including a horrific incident where two men were killed by an exploding boiler of a steam engine. They also had to contend with frequent floods. The Navvies also had a rather bad reputation of men who worked hard and played even harder, unwinding in the evenings with legendary drinking sessions that almost always ended in a mass brawl. The railway company was hit with several complaints from the police, landlords and members of the public, all of whom demanded that the men be properly managed.

Post link

Engineers on London’s Crossrail project find and unearth 25 graves from victims of the Black Death dated from around 1350. Signs have been found of more burials across Charterhouse Square and also the foundations of a building, possibly a chapel. Further examination of the bones suggest that these people lived lives of hard labour, suffered malnutrition and that almost half grew up outside of London.

Post link

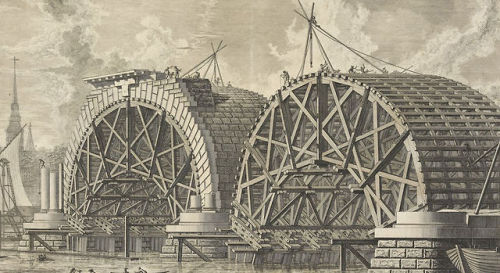

An engraving from part of the intended bridge at Blackfriars London by Giovanni Battista Piranesi showing the techniques of bridge building in 1763.

Post link

Rescuers free trapped passengers from a derailed train at the scene of the Harrow Train Crash where an incoming train crashed at speed into the rear of a local passenger train that had stopped at the station; within a few seconds of the collision an express train, travelling at speed in the opposite direction, crashed into the first train’s locomotive. The crash left 112 dead and 88 hospitalized, on the 8th of October 1952.

Post link

A crowd of poor people waiting in the snow, hoping to be let into a homeless shelter. East London,1857

Post link

On This Day in History May 31, 1859: The bell that was installed into the clock atop the 320-foot tall Elizabeth Tower known as “Big Ben” rings out for the first time. Why is it called Big Ben?

According to History.com:

“The name “Big Ben” originally just applied to the bell but later came to refer to the clock itself. Two main stories exist about how Big Ben got its name. Many claim it was named after the famously long-winded Sir Benjamin Hall, the London commissioner of works at the time it was built. Another famous story argues that the bell was named for the popular heavyweight boxer Benjamin Caunt, because it was the largest of its kind.”

Big Ben has withstood the elements and incendiary bombs during World War II to become on of the icons of the landscape of London.

#BigBen #HousesofParliament #BritishHistory #LondonHistory #ArchitecturalHistory #EngineeringHistory #History #Historia #Histoire #Geschichte #HistorySisco

https://www.instagram.com/p/CeOr3WUOhJm/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

Post link

Decades before he would take on the Nazis, Cadet Winston Churchill of the Royal Military College at Sandhurst launched his first foray into (politicall) battle as the (self-appointed) champion of sex workers, brandishing his wit against the “prudes” who demanded stricter regulation of prostitution.

It was the Naughty Nineties and Churchill, grandson of the Duke of Marlborough and son of the former Chancellor of the Exchequer, was caught up in the excitement of the popular reaction against Victorian Puritanism. The young soldier’s passion was the music hall and his favorite venue was the Empire, which featured a men’s bar alongside a promenade where dollymops and toffers strolled, advertising their services, showing off their wares and negotiating their fees.

When a crusader against prostitution with a name suited for a Monty Python sketch, Mrs. Ormiston Chant, succeeded in persuading local officials to separate the courtesans from their potential clients with a barricade, Churchill mustered his burgeoning skills as a political activist. He hocked his watch for funds to support a protest and on the evening of the third day of November, 1894, three weeks shy of his twentieth birthday, the cadet hopped onto a chair among the tipsy Empire clientele and declared, “I stand for Liberty!”

His first public speech triggered a lawless outburst which culminated in the destruction of the barricade. The sense he could motivate people with his words intoxicated Churchill. “It was I who led the rioters,” he wrote excitedly to his younger brother.

The victory was temporary. The London County Council sided with Mrs. Chant and the barrier keeping the vices of alcohol and prostitution separate reappeared. The Bishop of London chastised Churchill in The Times: “I never expected to see an heir of Marlborough greeted by a flourish of strumpets.”

Unapologetic, the heir of Marlborough wrote to his aunt, “It is hard to say whether one dislikes the prudes or the weak-minded creatures who listen to them most. Both to me are extremely detestable.”

Was Cadet Churchill a personal patron of the sex workers? Probably not, historians say. A music hall girl who spent the night with him reported, “Winston had done nothing but talk into the small hours on the subject of himself.”

In power, Churchill did not pursue formal decriminalization, but he continued to believe that using the legal system to oppose sex workers was, as he once told his father, “coercive and futile.” Prostitution flourished in London during the Second World War; even the streets of posh Mayfair were crowded with businesswomen offering succor to young soldiers. Cabaret star Florence Desmond sang what may have been a typical sales pitch:

I’ve got a cozy flat.

There’s a place for your hat.

I wear a pink chiffon negligee gown.

And do I know my stuff,

But if that’s not enough,

I’ve got the deepest shelter in town.

Churchill later recalled the Empire incident in his official biography. The old warrior said his speech had been “a serious constitutional argument upon the inherent rights of British subjects; upon the dangers of State interference with the social habits of law-abiding persons; and upon the many evil consequences which inevitably follow upon repression….”

(Additional sources: First Lady: The Life and Wars of Clementine Churchill by Sonia Purnell; The Last Lion: Winston Spencer Churchill by William Manchester; London in the Twentieth Century: A City and its People by Jerry White.)

Post link