#longitude

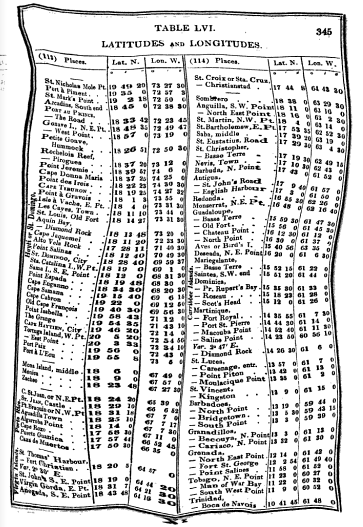

Distorted table of latitudes and longitudes.

From p. 345 of A New and Complete Epitome of Practical Navigation by John William Norie (1839). Original from Oxford University. Digitized October 24, 2006.

Post link

Summers end buts cry’s for that latitude / longitude of Venice…

.

.

.

#travelaway #venice #venezia #vistitaly #visitvenice #travel #travelgram #igtravel #thehappynow #travelbrilliantly #manmeetsfashion #lifestyle #tbt #italiano #italy #travelphotography #travelguide #beautifuldestinations #beautifulmatters #latitude #longitude #destination #igersvenice #igersitalia #venicecanals (at Venice, Italy)

https://www.instagram.com/p/BoytO8SHx0m/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=59fx9xue0vrs

Post link

A very loose map of the Galapagos Islands… definitely a fun one to draw. Recent cover for Longitude Books’ 2018 catalog.

Post link

ART AND SCIENCE I: Claude Mellan

The early 17th-century invention of the telescope facilitated the close observation of the topography, phases and motion of the moon. This type of astronomical inquiry had political and economic benefits. Before the invention of a sea-worthy chronometer in the 18th century, maritime longitude was calculated by using the moon’s consistent rate of motion relative to the stars. Seeking to improve the reliability of this method, astronomer Pierre Gassendi (1592-1655) and humanist Nicolas Pereisc (1580-1637) compiled a mass of data concerning the visible features of lunar surface for possible use in the maritime determination of longitude.

To illustrate their findings, Gassendi and Pereisc hired engraver Claude Mellan to produce large, detailed images of the moon informed by their research. Mellan was given access to a telescope in Aix-en-Provence, which he was instructed to use to generate large, detailed engravings of the moon in its various stages. He returned to Paris in 1637 with completed engravings for three images only to learn that Pereisc had died a year earlier. Although this effectively ended the project, the undertaking was not unproductive: Mellan’s suberb engravings derived from his own telescopic observations constituted the one of the major early modern convergences of artistic training and scientific endeavour.