#book arts

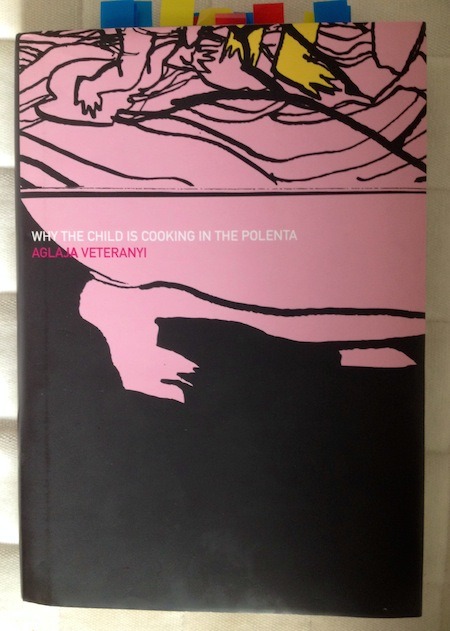

Our story sounds different every time my mother tells it.—Aglaja Veteranyi, Why the Child Is Cooking in the Polenta

My literary fathers tend to stick around. The late Gabriel Garcia Marquez lived a long, wild life, even if it ended in unjust and heartbreaking—yet poetic, inevitable—dementia. My literary mothers die untimely and tragic deaths.

Unless, of course, they’re Toni Morrison. But Toni is mother to us all; I can’t claim her for myself. She is the grand matriarch who refuses to lay down with every single word.

Yes, I have many mothers, but still I am waiting on my mother to come back for me. You—some of you few unlucky orphans—know this feeling. Having many literary mothers is a little like being raised by wolves. Having many mothers means you still nurse when the first mother looks away. Or when her body is scavenged by lesser animals, many of them inside of her.

My literary mother Angela Carter wrote her final novel after being diagnosed with cancer. Leaving behind a small son and husband, she still made a party of words. She wanted us to remember “What a joy it is to dance and sing!” In fact Wise Children—full of birthdays and babies and twins and magic and Shakespeare and Carnival—ends in incest between a seventy-five-year-old and her hundred-year-old uncle. What a way to go out, Angela. Mom, white-wine drunk again.

But I want to tell you today about my mother Aglaja Veteranyi, whom you probably never heard of, and who drowned herself in 2002 in Lake Zurich. A Swiss writer of Romanian origin, Veteranyi was part of a touring circus. Her stepfather was a clown and her mother an acrobat. She, herself, was made to juggle and dance. This is the subject of the novel Why the Child Is Cooking in the Polenta, which she published before she took her own life (other works were released posthumously).

My mother Aglaja is a child, herself. My mother is waiting for her own mother to return, because she has been abandoned at an orphanage. My mother Aglaja feels that “home is nowhere, betrayal is everywhere,” (195). She yearns for her mother’s polenta, which, in her native Romanian, mamaliga, translates roughly to “mother’s home cooking,” (197). Yet some part of her fighting for survival knows that to eat mamaliga is to eat poison. This, too, is how I know Aglaja is my mother.

The family was not Rom, but they were wanderers and outcasts, having fled poverty, austerity, and an illiterate Romanian dictator in 1967. The child narrator in Polenta feels dislocated because “Here [in this new place] everybody has warm water in their bathroom and a refrigerator in their heart,” (123). She understands that God is sad because he, too, is a foreigner. “Out of love for poor suffering humanity, God will eat polenta. He’s a foreigner himself, traveling from country to country. He’s sad because he has to start out on a long journey again,” (178).

WithPolenta, there is no dilution of Aglaja’s experience. Vincent Kling notes in his exquisite afterward, having had the vision to translate the work into English, that she is never detached. He explains that Aglaja’s voice offers the “adult retrospective viewpoint but at the same time the child’s passage through successive stages of awareness.” Every line is touching, funny, or pained. Everything is true. Always, she is with us.

I want to tell you about Aglaja Veteranyi because I read Polenta in a single sitting. I read this book looking up at Aglaja and thinking, how will I ever wear your clothes? I read this book thinking, Are you My Mother? I read this book thinking, You Can Be Nobody’s Mother. I read this and stopped every few sentences to write something. I read this believing that everybody should read this. I read this and felt afraid. I read this and thought of all those stories of the old witch who fattens children up to eat them. I read this and felt rage at not knowing the good-enough mother. I read this and thought how you can make a mother out of words. I read this and mourned because words are not always enough, not always. I read this and could not stop reading. I read this and knew what I wanted to be. I read this and knew where I came from. I read this and wanted to share my mother with you, so she could be your mother, too.

My father died of absence. My mother lives in helplessness. My sister is only my father’s daughter. I’ve grown up little by little. And I don’t want any children.—Aglaja Veteranyi

Recommended reading: Why the Child is Cooking in the Polenta, Aglaja Verteranyi, Dalkey Archive Press

EXTRA-SPECIAL JULY BONUS: Annie shares her smartypants annotations, saying “I am getting really intrigued by how people map texts (their own and others).”

We agree, and if you’ve any annotations or other visual media to share of your own literary mother (suggestions: altars to said idol, drawings, fan letters, collages, elaborate napkin notes, unsent sexts, autographs, marginalia, hair lockets, hair shirts, star maps, or assorted ephemera), send ‘em in, with or without an essay- we may add it as a regular feature!

Annie Liontas’ debut novel, LET ME EXPLAIN YOU, is forthcoming from Scribner in 2015. She is the recent recipient of a grant from the Barbara Deming Memorial Fund to conduct research in Trinidad for her newest work BADEYE, which also received Honorary Mention in the 2013 Dana Awards. Annie will be attending the 2014 Disquiet International Literary Program in Lisbon, Portugal on an Editor’s Choice Fellowship. Her story “Two Planes in Love” was selected as runner-up in BOMB Magazine’s 2013 Fiction Prize Contest and was published by BOMB in December. Other stories and poems have appeared in Ninth Letter,Night Train, and Lit. She graduated from Syracuse University’s MFA Program, where she was awarded the Creative Writing Department Fellowship and a 2013 Summer Fellowship. In 2003 and 2000 she received the Edna N. Herzberg Prize in Fiction at Rutgers University. Annie served as Editor-in-Chief of SALT HILL from 2012-2013. She co-hosts the TireFire Reading Series in Philly.

Decorative Paper Sunday

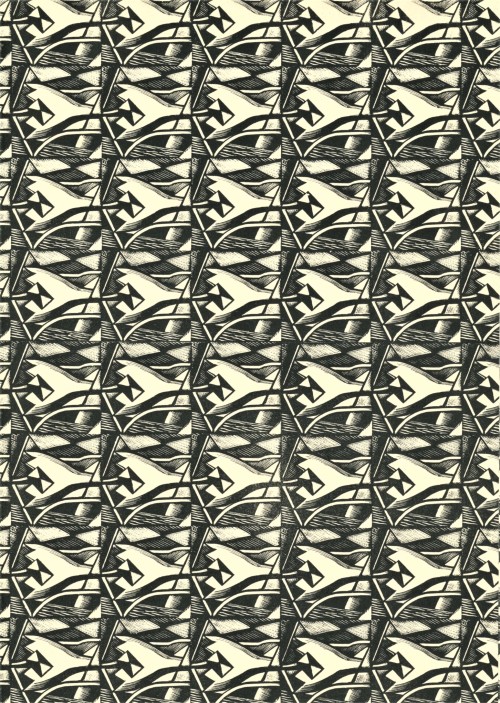

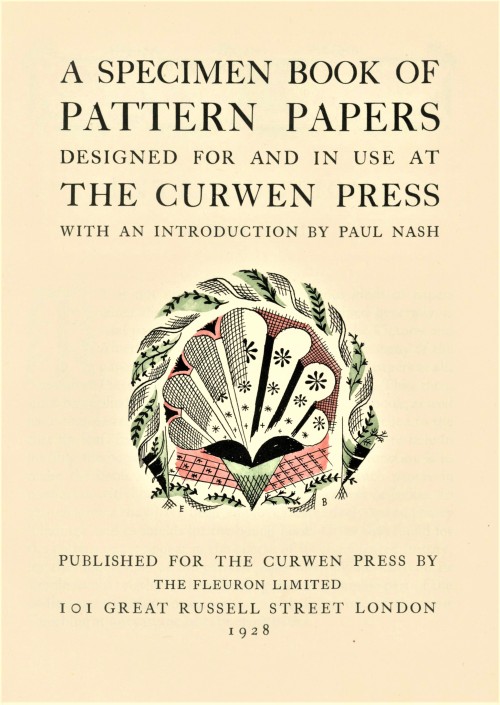

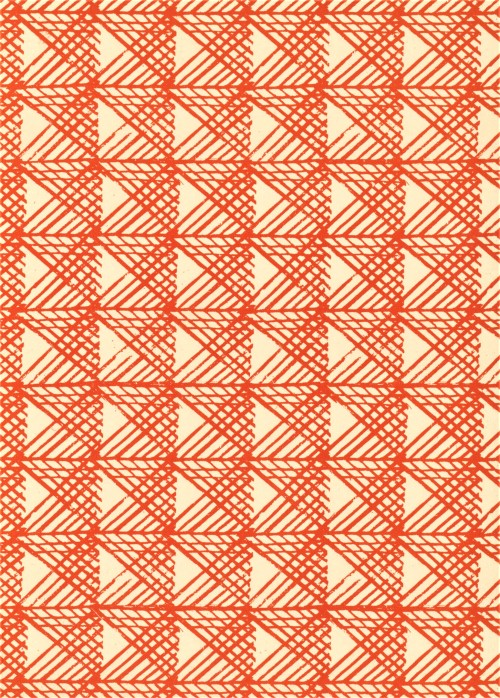

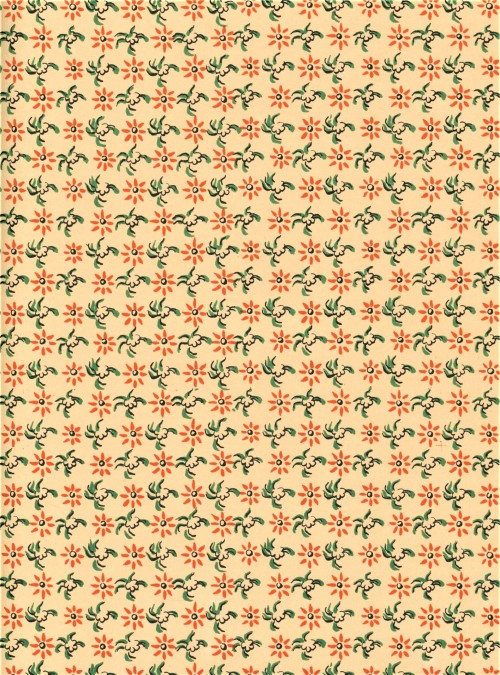

I’ve been excitedly waiting for this specimen book to make its way through processing and into our catalog so I can share these gorgeous decorative papers with you all. I hope some design nerds out there will share my enthusiasm. The book isA Specimen Book of Pattern Papers Designed For and in Use at the Curwen Press,published in London for the Curwen Press byThe Fleuron Ltd. in 1928 in a limited edition of 220, containing 31 samples of pattern paper, with an introductory essay by artist and Curwen collaborator Paul Nash.

From Nash’s introduction:

The papers in the following Collection are from designs reproduced by offset printing, the original key pattern being a line block from a drawing, or wood engraving … The latest designs are mostly from blocks engraved upon wood, sometimes with another colour applied either flat or grained. This notable output by an English printer is another sign of the steadily growing conviction that distinction of design is not only aesthetically, but commercially important. Every article, from the Shopman’s showcard to a motor-car, must have economy and beauty of form. It is a lesson we are learning very late, but if we can learn it intelligently, and not like parrots, we may yet recapture what has been so long lost with us, a pride in style.

The Reverend John Curwen established the Curwen Press in 1863 in order to produce hymn sheets for his congregation, where he was responsible for popularizing the tonic sol-fa method of sight singing. John’s grandson Harold Curwentook over management of the press in 1914. Inspired by William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement and invigorated by fresh design ideas after a sojourn in Leipzig, Harold led the firm in a new direction, focusing on typography, design, and collaboration with artists in print projects. The Curwen Press, together with its associates in the Design and Industries Association,were highly influential in 21st century printing and publishing in the West.

The Curwen Press closed in 1984, but the Curwen name lives on in the Curwen Studio. The studio was established in 1958 and managed by esteemed printmaker Stanley Jones and specializes in fine art lithographic printing.

See image captions for design attributions. This book was acquired with support from the John S. Best Fund.

You can find moreDecorative Sunday posts here.

Moreposts about the Curwen Press can be found here.

-Olivia, Special Collections Graduate Intern

Post link

‘does it hurt? / unprivate,’ 2020

mixed media

excerpts from artist’s book, invite my hungry mouth to eat

Peritextual collage: scratched-out bar code, printing and digitization statements, directions for use, author’s name.

From the back matter of Williams’s Letters: Letters Written in France in the Summer 1790 by Helen Maria Williams (1794). Original from the University of Michigan. Digitized November 15, 2005.

Post link

Tape repair.

From p.32-33 of The Tale of Old Mr. Crow by Arthur Scott Bailey (1917). Original from the University of Michigan. Digitized January 10, 2013.

Post link

Distorted map.

From the front matter of An Enquiry Into the Life and Writings of Homer by Thomas Blackwell (1757) Original from the New York Public Library. Digitized September 26, 2007.

Post link

Digitization equipment spread.

From the front matter of Catalogue of Stars by Caroline Lucretia Herschel and John Flamsteed (1798). Original from the Bavarian State Library. Digitized January 14, 2011.

Post link

1. Book printed.

2. Book microfilmed.

3. New print copy produced from microfilm copy.

4. New print copy digitized by Google Books.

Blank page from News from the Stars by Henry Newman (1691). Original from Indiana University. Digitized August 9, 2011.

Post link

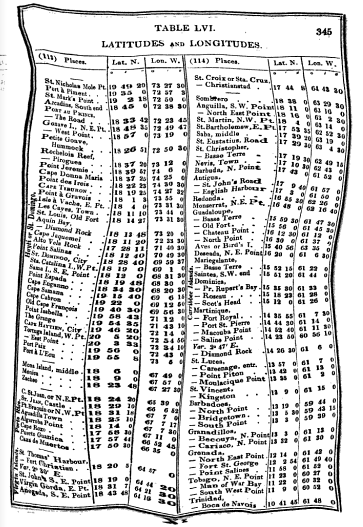

Distorted table of latitudes and longitudes.

From p. 345 of A New and Complete Epitome of Practical Navigation by John William Norie (1839). Original from Oxford University. Digitized October 24, 2006.

Post link

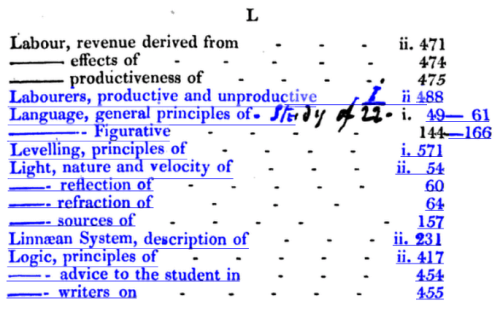

Blue links engage handwriting in the auto-table-of-contents.

From p. 598 of Systematic Education: or, Elementary Instruction in the Various Departments of Literature and Science, vol. 2 by William Shepherd (1822). Original from the University of California. Digitized August 31, 2007.

Post link

Rear cover swerve.

From the back matter of The Complete Works of the Rev. Andrew Fuller by Andrew Gunton Fuller (1848). Original from the University of Iowa. Digitized December 21, 2015.

Post link

Plates photographed through tissue.

Throughout Arthur’s Home Magazine, vol. 54 (1886). Original from Princeton University. Digitized April 18, 2008.

Post link

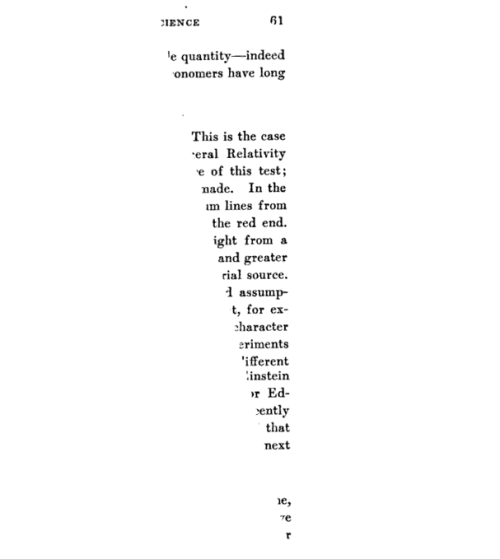

Acute textual triangle.

From p. 61 of University of North Carolina Extension Bulletin (1922). Original from the University of California. Digitized September 3, 2009.

Post link

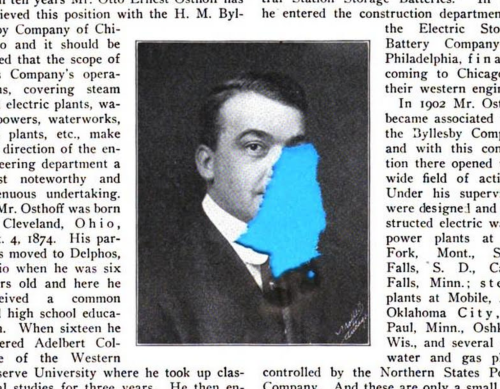

Hole photographed with blue paper behind it.

From p. 540 of Popular Electricity and the World’s Advance, vol. 4, edited by Henry Walter Young (1911). Original from the University of Michigan. Digitized May 11, 2011.

Post link

Employee’s hand.

From p. 72-73 of Red Feather: A Comic Opera in Two Acts by Reginald De Koven and Charles Klein (1903).

Post link

Illustration photographed through tissue.

The frontispiece toDotty Dimple Out West by Sophie May (1869). Original from Harvard University. Digitized March 25, 2008.

Post link

Foxing blurred by movement.

From the front matter of On the Present Balance of Parties in the State by John Benn-Walsh (1832). Original from Oxford University. Digitized April 10, 2006.

Post link

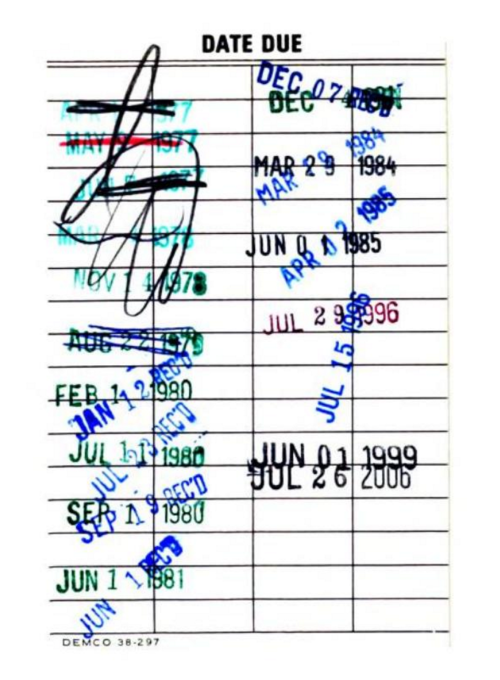

Circulation slip, with checkouts between and 1977 and 2006.

From the back matter of A Theory of Pure Design: Harmony, Balance, Rhythm by Denman W. Ross (1907). Original from Harvard University. Digitized March 7, 2007.

Post link