#mammal

Black and white Lemur, taken at the Erie Zoo.

I’m really proud of this one!

As you should be!

Post link

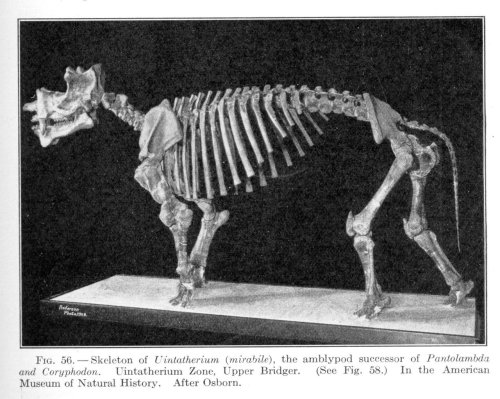

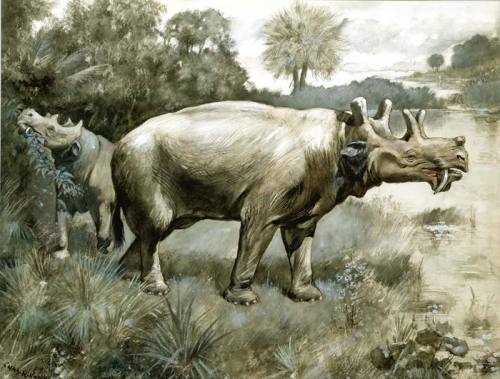

Uintatherium

Mounted specimen from American Museum of Natural History, and currently part of the traveling Extreme Mammals exhibit.

Reconstruction by Charles Knight

When: Eocene (~49 to 39 million years ago)

Where: North America

What:Uintatherium is one of the first large mammalian herbivores. It stood about 6 feet (~1.8 meters) high at the shoulder and was roughly 13 feet (~4 meters) long. This isn't that large for an animal today, but in the Eocene it was a giant! It lived in the lush sub-tropical forests of mid-Eocene North America, most likely eating a combination of terrestrial bushes and shrubs along with aquatic plants from lakes and marshes. Uintatherium has a nasty pair of upper canines, not what you would expect from a herbivore! It is thought that these teeth were involved in sexual display, as they appear to be much larger in males than females. Uintatherium vanishes from the fossil record in the late Eocene, at about the time the temperature of North America was falling and the vegetation was thinning out.

Uintatherium was also one of the fossils involved in the great ‘Bone Wars’ between Cope and Marsh. It was by far the largest of the fossils to come out of the Fort Bridger fossil localities in Wyoming (this fort gives its name to a land mammal age - The Bridgerian!), and thus highly prized. Cope and Marsh both applied multiple names to specimens from this region which would later prove to all belong to the same species. The name Uintatherium wasn’t even one applied by Cope OR Marsh. Joseph Leidy named this creature in 1872, just barely edging out Marsh’s names of Dinoceras and Tinoceras. So that particular battle in the bone wars was won by someone who didn’t even have much of an interesting in fighting!

Uintatherium is not thought to have any living descendants, it is possible that the Eocene Uintatherium was the last of its kin. However, the position of Uintatherium and its brethren (grouped as the Dinocerata) within the mammal family tree is highly uncertain. They are well accepted as placental mammals, but beyond that? It is highly debated, and in my opinion, nobody has really done a rigorous enough study to support any one position over another.

Post link

Obdurodon

Skull on display at the American Museum of Natural History, NYC

Reconstruction by Anne Musser

When: Late Oligocene to Miocene (~25 to 12 Million years ago)

Where: Australia

What: Obdurodon is a fossil platypus, as is fairly obvious from a look at its skull. Though upon closer inspection there are some very important differences; Obdurodon had a larger bill than the living platypus and retained teeth as an adult. Modern adult platypus are toothless, shedding all their teeth as juveniles. These teeth are important as they help us place monotremes (platypus and the echidna are the modern representatives) into the mammal family tree. It is now the consensus that marsupials and placentals are more closely related to one another than either is to the monotremes, but there are a great deal of extinct groups of mammals that may fall between therians and the monotremes - such as the multituberculates. Fossils such as Obdurodon which are most assuredly related to modern monotremes, but preserve more primitive features, are critically important for this phylogenetic issue. So then why is it still an issue? All we have of Obdurodon is a skull, despite the full body reconstruction above, and while there are fossils of even older monotremes they are even more scrappy - just isolated teeth or jaw fragments (that still enjoy full body reconstructions…).

How did Obdurodon live compared to the modern platypus? Well, the living form uses its bill in the water to help it sense prey, and as Obdurodon had an even larger bill, it seem likely it also was aquatic, though without a postcranial skeleton it is unknown if it had the same swimming and digging adaptions seen in its extant relatives.

Post link

Palaeolagus

When: Late Eocene to Mid Oligocene (~38 to 27 million years ago)

Where: North America

What:Palaeolagus is a fossil lagomorph. Lagomorpha is an order of mammals, that contains rabbits, hares, and pikas. Within the bunny-order rabbits and hares are more closely related to either other than either is to the pikas. If you are not familiar with pikas go check out some pictures! They are really cute little guys that resemble guinea pigs more than they do rabbits, but they are most assuredly lagomorphs. Palaeolagus falls outside all living lagomorphs in their evolutionary lineage. It can be thought of as representative of the common ancestor of all living lagomorphs.

Palaeolagus lived in North America in the late Eocene, after the dense forests had left and the grasslands of the plains started to expand. This 10 inch (~25 cm) long herbivore spread throughout the continent during the Oligocene as the grasslands grew. Palaeolagus could not hop, its hind legs show none of the features that make a hopping locomotion style possible in living rabbits.This ancient bunny is known from a large amount of fossil specimens, some of which are almost complete skeletons, but most are fragmentary pieces of bone or teeth. Most of these Palaeolagus specimens likely met their end as the lunch of one of the many predators roaming the grass lands of prehistoric North America.

Post link

Procoptodon - The giant short faced kangaroo

Mounted skeleton on display at Victoria Fossil Cave, Naracoorte Caves National Park, South Australia

Reconstruction by Peter Trusler.

When: Pleistocene (~ 2 million to 15,000 years ago)

Where: Throughout Australia

What:Procoptodon is a giant fossil kangaroo. Exactly how ‘giant’ it is has been a bit exaggerated, heights of up to 10 feet (~3 meters) have been reported, but this would have been its maximum height when it reared up fully on its hind legs, with its arms reaching up for high branches. Procoptodon was capable of this posture, but (like living kangaroos) it did not stand fully upright most of the time. In its normal feeding (and most everything else) poster it would have stood about 6.5 feet (~ 2 meters) tall; about the same height as the largest of the modern red kangaroos. Procoptodon was not the same size as these animals though, it was much more massive and would have been over twice the weight of a red kangaroo of equivalent height.

Procoptodon was very well adapted for the semiarid conditions that characterized much of Australia during the Pleistocene, but fossil remains have also been found in the more hospitable regions of prehistorical Australia. The marsupials of Australia are well known for their convergence evolution upon forms from other continents (such as the tasmanian tiger and the marsupial mole), but the kangaroo does not look like any placental mammal known. However, in terms of its lifestyle, the ecological niche that it inhabits, the group is convergent upon hoofed animals, such as deers! Procoptodon overlapped with human habitation of Australia, and it is thought some Aboriginal folktales are about this massive kangaroo.

Procoptodon is a member of the group Sthenurinae - the shortfaced kangaroos. As you probably guessed these kangaroos had much shorter snouts than the modern species of kangaroos. This group is completely extinct. It is one of the subgroups of the Macropodidae, the clade of marsupials that contains all kangaroos and wallabies, as well as a few other groups. It has been proposed that within the Macropodidae the closest living relative of Procoptodon is the Banded hare-wallaby, though this is not universally accepted.

In the prehistoric outback Procoptodon would have co-exsited with the largest marsupial of all time Diprodoton and was a hunted by the marsupial lion Thylacoleo. And the second link you can see this marsupial predator hunting a close relative of Procoptodon!

Post link

While the vaquita is not deliberately hunted by humans, its downfall has been the extensive fishing of the totoaba, a fish whose swim bladder is a delicacy in China. Gill nets used to catch totoaba have quite literally massacred the vaquita - over 80% of their population disappeared between 2008 and 2015.

Government efforts to preserve the species were perfunctory - “vaquita-safe” nets proved nowhere near as effective as the old gill nets, fishermen rioted when a related fishery was shut down for fear of it being used as a cover for tatoaba poaching (ironic, as that fishery used safer nets), and compensatory monthly checks to men losing their livelihood were meager, sometimes less than a man could make in a single day’s fishing. The export of tataobas was banned and a marine reserve established, but poaching and smuggling is rampant, and there is little incentive to stop it. A single tatoaba bladder can bring in $20 000, while the fine for being caught poaching is about $500. Even now, the controversial Sea Shepherd is one of the few ships patrolling for poachers, and they can do little but film and report them. In the meantime, dead vaquita continue to be pulled from the waters.

The latest estimates say there may be only 12 vaquita left in the world. If the vaquita goes extinct, it will be the first extinction of a marine mammal since the loss of the baijiin 2006.

Post link

Thevaquita has the most restricted range of any marine cetacean, as they are endemic to the northern end of the Gulf of California. They have evolved to live in shallow, murky water, sometimes so shallow that their backs protrude from the water. Unlike many other marine animals, they can also cope with the rapid and extreme temperature changes that can occur in shallow water.

Post link