#obstetrician

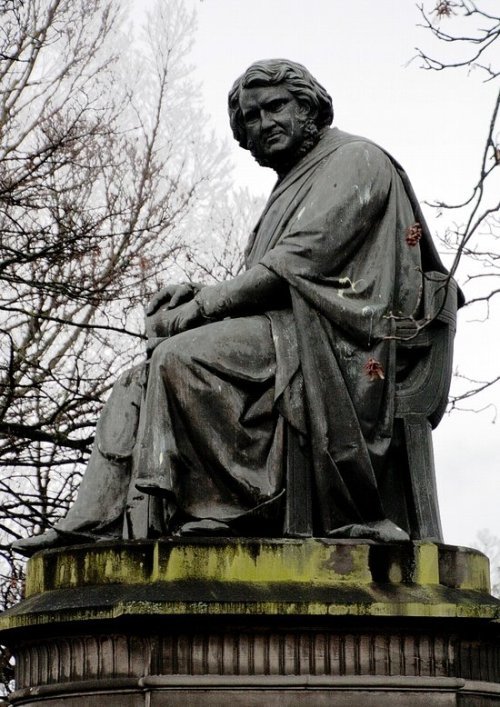

May 6th 1870 Sir James Young Simpson, the Scottish physician, died.

James was born the seventh son and eighth child of poor baker on 7th June 1811 in Bathgate, West Lothian. He was apprenticed to his father, but spent his spare time working on scientific matters, and, thanks to a scholarship and help from his elder brother, he entered the arts classes of the University of Edinburgh in 1825, at the age of fourteen, an began the study of medicine in 1827.

He studied under Robert Liston and received his authorisation to practice medicine – licentiate of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh – in 1830. He was then 19 years old and subsequently worked for some time as a village physician in Inverkip near Wemyss Bay on the Clyde. Two years later he returned to Edinburgh where he received his medical doctorate in 1832. The professor of pathology, John Thomson entrusted him with some lectures, and in 1835 he was made senior president of the Royal Medical Society of Edinburgh.

Following hard efforts, Simpson in 1839 at the age of twenty-eight years, was appointed to the chair of obstetrics at the University of Edinburgh. Lecturing in obstetrics had been somewhat neglected at the university, but Simpson’s lectures soon attracted large numbers of students, and his popularity as a physician reached such proportions that he could soon count women from all over the world among his patients. Besides his activities as a scientist and teacher he had a very busy – enormous, really – practice.

Simpson was president of the Royal College of Physicians in 1849, in 1852 he was elected president of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, and one year later was elected foreign member of the French academy of medicine. He received several honours and awards, in 1856 the golden medal from the Académie des sciences and a Monthyon prize. In 1847 he was appointed one of the Queen’s physicians for Scotland. In 1866 he was knighted and that year also became doctor of honour of law at the University of Oxford. In 1869 he received the freedom of the city of Edinburgh.

That’s the qualifications out of the way, ordinarily this would be enough for any leading man of medicine to be remembered by, but Simpson was no ordinary man, let’s get down to the nitty gritty.

Simpson combined intellectual brilliance with compassion. Distraught after witnessing the practice of surgery without anaesthesia, Simpson wrote of “that great principle of emotion which both impels us to feel sympathy at the sight of suffering in any fellow creature, and at the same time imparts to us delight and gratification in the exercise of any power by which we can mitigate and alleviate that suffering.”

So he started working on ways to deviate the pain felt in the neglected world of obstetrics, namely childbirth. At first this seemed a forlorn hope. Simpson tried mesmerism, but the hypnotic method brought only limited results. After trying other medical means like ether he read about chloroform being used in dentistry and surgery in the US, yes it had been used before, but never in in his field, and it was he who pioneered it’s use. In these days religion played a big part in everyone’s lives, and the belief that women were meant to suffer pain in childbirth was the main argument against his work.

It has been written there was a savage religious response, especially in Presbyterian Scotland, to his use of chloroform – in reality the attack on Simpson’s enthusiastic promotion of chloroform was brief, sporadic and of little moment. Simpson’s carefully constructed counter to criticism of anaesthesia, drawing on considerable theological and linguistic expertise, reveals a complexity at odds with the simplicity of his faith. Simpson was a great orator and by all means a charismatic man, his arguments for it’s used won over the vast majority of it’s critics, the rest, as they say, is history.

I’m not one to usually member honours bestowed on people by royalty, but you have to admit in this case it was merited, In 1866 Simpson was the first man ever to be knighted for his services to medicine.

Post link

Adding choline to pregnancy diet can improve sustained attention in kids.

[image: the card I carry with to explain epidurals during labor, created by Penny Simkin]

I had a few requests for me to share my epidural informed consent ‘script’, so here it is in it’s MOST general version. Please remember that this is just an idea of what I might say, and it would definitely be different when I am with a laboring person, as I take their specific health and priorities and concerns and personality into consideration when I discuss this with them. This script is for someone who is undecided during labor about whether or not they want an epidural and is asking for more information.

*Of note: I don’t bring pain medication up without them starting the conversation unless I see them truly suffering. If I bring it up and they say no, I don’t bring it up again.

The conversation usually includes a few parts:

- Explaining what an epidural is and how it works

- Explaining the process for inserting the epidural

- Discussing risks, benefits, and alternatives

- Reviewing everything, answering questions, and then stepping out of the room to give them time to discuss if they would like that.

- Occasionally it may include offering a vaginal exam ahead of time if they think the information gleaned from the exam would change their decision

“I remember from your birth plan that you didn’t want to talk about pain medication unless you brought it up yourself - now that you’ve mentioned that you might want an epidural, do you feel like you’d like to talk about it? There’s no rush since I KNOW that you can do this and ARE doing this in the exact right way for you right now.”

If yes, I continue.

“Epidural anesthesia is a pain medication that numbs you from here [show them the top of the uterus/diaphragm area] down to your toes. Everyone experiences them differently, so some people are completely numb and cannot even move their legs, while most people have some control over their legs but are numb enough to not feel the intensity of the contractions any longer. While you won’t feel the intensity, you will still likely feel the pressure of contractions or of the baby’s head as the descend in your pelvis, and you will still feel touch to the skin. You will definitely feel the baby’s head coming out, and that may be painful or intense even with the epidural in place. Our anesthesiologists usually do an epidural that allows for your legs to move, and so we will definitely help you into whatever position you need - sitting up, lying down, squatting, hands-and-knees, lying on your side - as long as you are still in the bed. It’s not usually safe to try standing with the epidural since most people don’t have enough sensation in their legs to hold their weight.

“The way they place the epidural is they have everyone but one partner/doula/support person step out of the room and you sit at the edge of the bed with your shoulders slumped over. The anesthesiologist will give you a numbing shot to the skin on your low back which some people say is the most painful part of the whole ordeal - it feels like a bee sting. Once that area is numb, they insert a larger needle into the epidural space, in your spine. [I carry an illustration of this to explain what I mean.] Then just like an IV in your arm, a tiny plastic catheter (tube) is threaded into that space and the metal needle is removed. The epidural medicine drips in a small amount at a time through the catheter. This way we can give you more or less medication at any time depending on what you want or need. Sometimes we will increase the medication if the regular rate isn’t strong enough, or we will decrease if you need more sensation to move or push. It usually takes about 15 minutes to place the epidural and 15 minutes for it to start working.

“In order to have an epidural placed you will need an IV running fluids through your arm, continuous fetal monitoring, and a urinary catheter since you won’t have enough sensation to empty your bladder yourself.”

When it comes to talking about pros and cons I talk specifically about each person’s scenario instead of more generally, since the person I’m talking to is in labor! They don’t have much ability or desire to be thinking about anything that isn’t directly pertinent to them. Because of this I will discuss the epidural’s effects on the part of labor that they’re in now vs the future, but ignore the past. As in, if they’re in active labor I won’t talk about how an epidural might slow down early labor, but I might talk about it’s effects on pushing. For example:

“At this point you are in what we call ‘early labor,’ which means that your labor is still ramping up. It doesn’t mean that early labor is necessarily easier or that you will be in this place for much longer, but I have seen labors slow down when people get an epidural at this time. If that happens, we will talk about trying to stimulate your labor again either by position changes (though slightly limited in bed), nipple stimulation, membrane sweep, or pitocin. If you are coping well and able to go another hour without pain relief, I would recommend that we continue without. However the minute you tell me you have decided on epidural pain management, I will call the anesthesiologist. You are the only one who knows what’s right for your body.”

Another option for someone in active labor:

“At this point in your labor it’s unlikely that your contractions will slow down if you get an epidural, and in fact it’s possible that the relaxation of your pelvic muscles that comes with an epidural could allow baby to descend more and help to open your cervix with the pressure of their head. There’s no knowing what will happen either way.”

“The main risks to an epidural are the possibility that:

- Your contractions may space out [discuss what this would mean for their labor]

- The possibility of a postpartum headache (this headache happens to about 1 in 100 people and is treatable with pain meds, but is still a very frustrating experience in the postpartum period)

- The possibility that your blood pressure will drop and therefore your baby’s heart rate will slow (if this happens you can expect us to move you from one side to another, give you a ‘bolus’ aka large about of IV fluid, and maybe give you oxygen through a mask. Sometimes this can be scary because many Drs & RNs will come into the room all at once to address the issue. Though this may seem scary, when it is treated with the usual measures, it does not cause harm to baby or increase the risk for cesarean birth.)

- The possibility that the epidural won’t work at all or will have a small ‘window’ in which the epidural doesn’t work. If that happens our options are to grin and bear it, to try boosting the dose, or to take it out and try replacing it entirely.”

Here is a more extensive chart from LaborPains that I bring out sometimes when people are interested/in the right mind space to discuss further:

“The research is ambiguous when it comes to whether or not the medications passing through the epidural will affect the baby as well as the laboring person. There are no known long term disadvantages for babies. Babies are much less affected by epidurals than other medications used in labor that are administered by IV.”

“There are other things we could use as well to support you in coping with these contractions:

- Nitrous oxide - laughing gas (aka gas and air)

- IV medications (Morphine, Stadol, Fentanyl, Nubain, Demerol)

- Hydrotherapy - hot water in the tub or shower

- Sterile water injections - local pain relief without medications for back pain

- TENS units

- Massage, position changes, labor support”

See my post going into depth on those topics here.

“What questions do you have? Would you like me to step out for a moment so you can discuss this with your partner/doula/support person?”

Occasionally, if I think it would be useful, I will offer a vaginal exam before an epidural. For some people going through transition, the knowledge that they are close can give them some very needed encouragement. Vice versa, the knowledge that the cervix has not changed in many hours can also give people the information they need to decide that they would like an epidural.

“Would you like a vaginal exam before you decide on whether you would like pain medication or not? Many homebirth midwives will almost never use vaginal exams since they are quite right in thinking that vaginal exams don’t change the course of labor. However, in a hospital setting things change. There are interventions like epidurals to be considered, and a vaginal exam can give useful information to someone deciding on using an intervention. The exam itself IS an intervention in its own right. The information derived from a vaginal exam may tell us what stage of labor you are at right now. It does not tell us what will happen in the next 5 minutes (I’ve seen people dilate from 5cm to 10cm in 5 minutes) or in the next 5 hours (I’ve seen people be fully dilated for 5 hours before starting to push or giving birth). A vaginal exam is not required before you get an epidural, though. If you know for sure that’s what you want right now I will call the anesthesiologist right away.”

Resources:

Pain Medication Preference Scale - by Penny Simkin, for use before labor

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279567/