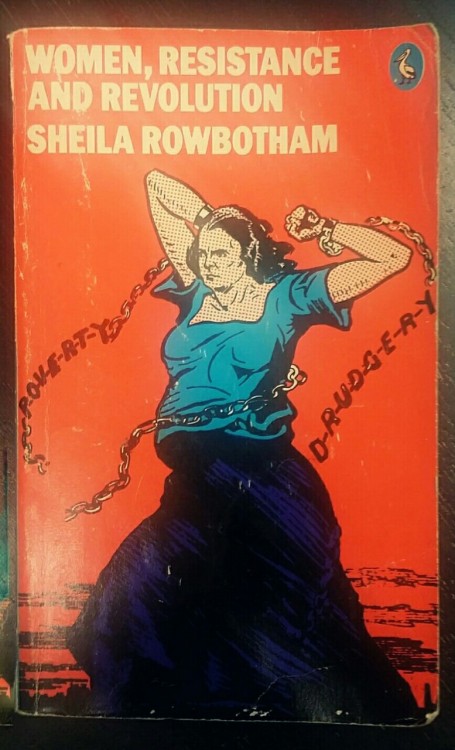

#penguin books

“It is only through writing that I become myself”

― Werner Herzog

“Read, read, read, read. Read, read. Read.”

― Werner Herzog

(We cannot agree more)

As we explained in the previous post, we love books. And again, it’s a pleasure when we participate in a publication with one of our images on the cover. But we must say that this one is a very, very special one for us because of the author of the book: Werner Herzog.

Herzog is someone who we highly admire. His films, documentaries, books, articles, courses and his philosophy of life has influenced the way we work. So, we feel honored with the humble contribution of our image to the cover of “The Twilight World”

In this novel, Herzog tells the incredible story of Hiroo Onoda, a Japanese soldier who defended a small island in the Philippines for twenty-nine years after the end of World War II.

Looking forward to reading it soon (to be released by Penguin on 07/07/2022)

Thank you very much to Penguin Books for having thought of our work for the cover of Herzog’s novel.

PS: “Read, read, read, read. Read, read. Read.”

A WORD FROM THE AUTHOR

Mona Awad, author of 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl

Daredevils by Shawn Vestal

By Josh Hanagarne

Every time I read a book in which Mormonism–in this case, its most fundamentalist strain–is the backdrop, I fear that I lose all objectivity. I was raised in the LDS church and had a very happy childhood. Since I’ve left, I’ve been forced to confront some of the darker aspects of the organization and have experienced predictable periods of anger, resentment, doubt, et cetera. When I read a book where Mormons of any strain are potrayed eccentrically and I catch myself thinking, “Yeah, what a bunch of weirdos!,” I take a step back to see if I think I’m being overly biased. I don’t like it when the members of a church–or any church–are rendered like Flannery O’Connor’s or Carson McCuller’s southern grotesques.

It’s temping. It’s occasionally deserved. But it doesn’t serve the reviewer or the reader.

Happily, there are two things I can say about Daredevilsright out of the gate:

It gets fundamentalist Mormonism right, particularly the mood of such in the 70’s, and Shawn Vestal’s writing and storytelling gifts are such that I didn’t find my own history interrupting my reading at all.

Daredevilsoffers a unique take on the Coming of Age Tale. Loretta is a fourteen year old living in a Fundamentalist Mormon community. She lives in one of the communities that tend to get raided by the feds.

She frequently sneaks out to fool around with an older man who promises her that he’ll take her away from it all very soon.

It doesn’t happen soon enough. Shortly after the book begins, she learns that she’s been “promised” to one of the community elders. Now she’s going to become yet another of his wives. Her early interactions with her new husband are some of the most depressing pages I’ve read. Loretta is trapped already, and now she knows she’s adding another layer to her captivity and there’s nothing she can do about it.

This is all happening during the period when the daredevil Evel Knievel is preparing to make his Snake River Canyon jump on the motorcycle. Right away we’re set up for the idea that Loretta breaking away from her upbringing and faith is every bit (or more) the daredevil act, just as much as anything Knievel could come up with.

I’d say her situation is way more intriguing. Knievel at least had a parachute. Loretta is fifteen, with all the limitations that can accompany the age, complicated further by her status in the religion.

After she marries, her new husband (Dean Harder, like something out of porn) moves his family. Loretta has to go with him and this is where the story really begins. Her husband’s nephew, Jason, a boy of endless pop culture enthusiasm and a devotee of Knievel, gives her a chance to be a kid again. They make an impulsive choice and hit the road together, along with one of Jason’s friends.

The trip they take is every bit as sad, frustrating, and fun as you might imagine, There were few things I enjoyed as much as teenage roads trips, and I never had anything to escape from. I just liked to go and laugh with friends. Loretta’s dash for freedom is worth cheering about and I enjoyed every page.

There are also some immensely enjoyable scenes where someone who may be Evel Knieval pops in and out.

Vestal writes wonderful dialogue and has such an obvious affection for Idaho, for Loretta, and for his lucky readers, that Daredevilswas irresistible for me from word one.

The child forced to grow up too soon is an endlessly fascinating trope. This is a portrayal of a child forced to grow up too soon in some very odd circumstances. Full of heart and joy, Daredevilsis one to read at least twice.

Post link

Libraries and Me

By Elizabeth George

I’m a lucky woman. I have enough money to buy all the books I want, and as a result I’ve filled my own library, my office, my assistant’s office, and my bedroom with books. I have never been without a book to read for as long as I can remember, and while I’m reading one book, there is another waiting. When I reach the last page of a book, I sigh, feel immensely gratified, sometimes write to the author, and then grab for the next one.

I began buying books when I was in seventh grade and began babysitting for neighbors. Books—along with Christmas presents—were how I spent that first earned money. I’m aware, though, that not everyone is as lucky as I am, and for this reason we have libraries.

Prior to my having that aforementioned babysitting money, I had no funds to purchase books and although I always received a book at Christmas, as did my brother, we made short work of them and we usually finished reading them before New Year’s Eve. So early on, my father took us to the Mountain View Public Library.

In those days, Mountain View, California, was not the place it is today: abloom with techies—and the industries they work for—and filled with restaurants, coffee houses, and some of the most expensive real estate in the state. Then—in the 1950s—Mountain View stood on the edge of farming land, huddled alongside the south end of San Francisco Bay where, picturesquely, the city dump was a sea gull’s paradise. Downtown featured a shoe store, a dress shop, a real Italian delicatessen, an equally real meat market, and a grocery store with saw dust on the floor. Tucked nearby this store—ah, I recall its name: Purity—was the public library. This was a storefront, and when we went inside, we were greeted by a librarian whom I can see at this moment, mostly because she had a mustache. We were allowed to wander along this tiny library’s few tall bookshelves and we could select as many books as we wanted. So we did. Some we read in the car on the way home. Others we set aside and doled out to ourselves. For we didn’t go to the library every week, only when the books were due, two weeks later.

In the summer, there were reading contests. When you finished a book, a balloon was colorfully filled in on a dittoed sheet of paper with your name on it. This featured a clown holding a whole slew of balloons, and it was with a source of pride that I saw my clown’s balloons get filled in quickly, faster than anyone’s.

Ultimately, a bigger library was built as the little town began to grow. A fine building not far from the Catholic church now housed the city’s books, and I can remember going there repeatedly and gnawing at the bit until the moment the next Anne of Green Gables book was returned by whoever had borrowed it. That same library is even larger now, but I haven’t been inside. Long ago, I moved away from Mountain View to seek libraries elsewhere.

My favorite was the old and wonderful library in the British Museum. My British publisher arranged for me to have a card there. I remember exactly what he wrote: “Please allow our distinguished author Elizabeth George entrance to the library,” and upon this merit, I was given a card. How proudly I passed the people in line to get into the museum when it opened. I didn’t have to wait in that line because the library was already open and…I had my card.

The library was a quirky and wonderful place where you could sit exactly where some of the great writers of English literature sat before you. You occupied a position in a large circle, row upon row of curved spaces upon which you could do your reading. Up above you: a deep blue ceiling. All around you: individuals studying, scribbling away on notepads, creating masterpieces….Who really knew? I was there to find books that would assist me in my understanding of the Pakistani experience in Great Britain in advance of writing a novel that I called Deception on His Mind. But…there was something about the British Museum’s great library that I didn’t understand at first.

The library is vast. Its books are not on view. There were no stacks to wander along. What you had to do was put your request in and wait and wait and wait—sometimes days—for the book to arrive. What I learned later from my publicist who had worked in the library was this: The stacks occupied an enormous place below ground, so enormous that unless the librarian assistants below had more than one book requested from a given area, they didn’t fetch the one you requested. Until, of course, they had another request! Consequently, it was many days of returning to the library before I finally received my books. I’m happy to say that they were very helpful. How irritating it would have been had they not been so.

Libraries exist for reasons. One of those reasons is scholarship. The other—and far more important, I think—is accessibility. Libraries give young children an access to a reading experience they might not otherwise have. They allow people who cannot afford to buy a volume of their own a chance to read the latest book in a series they love or a best seller that they’ve read about. Now, as a novelist who supports herself by selling books, I want people to frequent bookstores, of course. But I also want them to support their local library for what it can offer anyone—like the child I was—who walks inside.

Post link

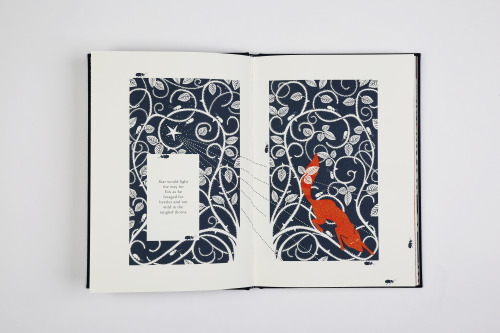

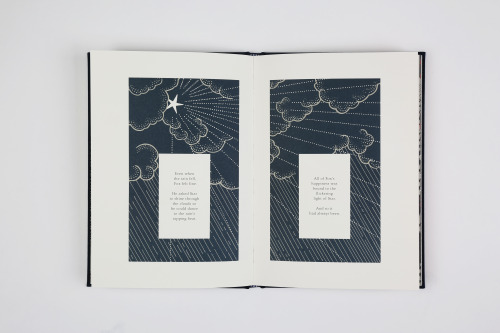

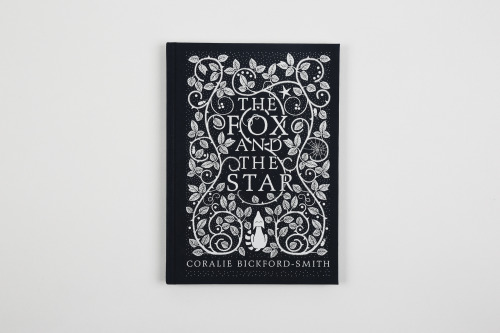

Be sure to check out the beautifully drawn fable The Fox and the Star by Coralie Bickford-Smith. You may her work as she is also the talented artist behind our gorgeous Penguin Classics Hardcovers.

Post link

A WORD FROM THE AUTHOR

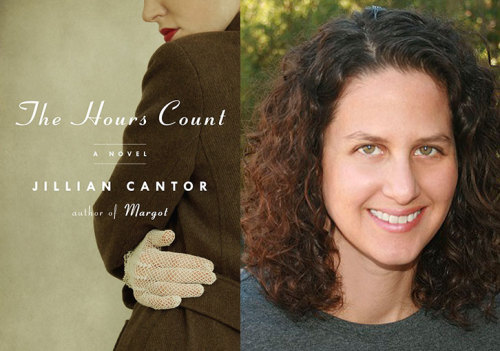

A letter from Jillian Cantor, author of The Hours CountandMargot

My favorite place to go as a kid was my local library. Every summer my mom would take my sister and me, let us check out ten books (the limit at the time), and then promise to bring us back when the books were all read to check out ten more. For me, that would usually be two or three days later. I’d spend my entire summer vacation devouring books outside by our pool, staying up late into the night reading in bed. One summer, when I was maybe eleven or twelve, I read through every single age-appropriate book the library owned by mid-July. The librarian then started setting aside adult books for me; she’d have a pile already waiting when I showed up to return my previous ten. I think that was the summer I read through Stephen King.

As an adult and a mom, I make just as many trips to my local library. My kids started young, going to story times as toddlers and leaving with overflowing armfuls of picture books. Now they have bigger arms, and they check out bigger books, but still, we always leave the library with piles of books almost too much to carry. When we moved a few years back, one of the first things we did was find our closest library.

A few years ago, on one of those many library trips with my kids, I grabbed a book for myself, as I often do. It was an anthology of women’s letters, and it was perfect to read through a little at a time with my busy kids in the house. I didn’t know it then, but this anthology would become the starting point for my new novel, The Hours Count, which re-imagines the years leading up to the arrest and execution of the Rosenbergs through the eyes of a fictional neighbor.

There were two letters in that anthology that really gave me the inspiration for my novel. The first was a letter a woman wrote to her friend in the early 1950s about her experience of giving birth. She recounted how she smoked cigarettes the whole time she was in labor and how she was knocked out for the actual birth. Though I found these details shocking, I learned they were not so shocking for the time, and it made me start to think about how motherhood was different (and the same) in the 1950s. The second letter was the one that Ethel and Julius Rosenberg wrote to their sons on the morning of their execution in 1953, imploring them to remember that they were innocent.

Even after I returned the anthology to library, I wanted to know more, and so I checked out a book about the Rosenbergs’ case. As I began to research, I quickly came to believe that Ethel really was innocent. The only evidence against her was her brother’s testimony that she typed up notes, which years later, he admitted was a lie. I also learned that when she executed, Ethel’s sons were just six and ten (only a little older than my own sons at the time). And I read that on the day Ethel was first arrested she left her sons with a neighbor. This was where my novel began to take shape, as I invented a fictional neighbor, Millie Stein, with which to tell my story.

InThe Hours Count, my fictional Millie is also a young mother, struggling with her child who won’t speak and a suffocating marriage. But when she moves into Knickerbocker Village in 1947, she befriends Ethel Rosenberg. My novel is ultimately an exploration of motherhood and friendship in the late 1940s and early 1950s, but it is set against the backdrop of the true and terrifying historical events that unfolded as the Rosenbergs were arrested and then executed, leaving their two young sons orphaned in 1953.

WhenThe Hours Count is published this October, I look forward to visiting it in my local library, where I hope other voracious readers and frequent library-goers like myself will pick it up. In the meantime, I’m still making weekly trips to the library with my kids. I know, somewhere inside, there is already another book waiting for me that could lead to the idea for my next novel.

Post link