#university of tokyo

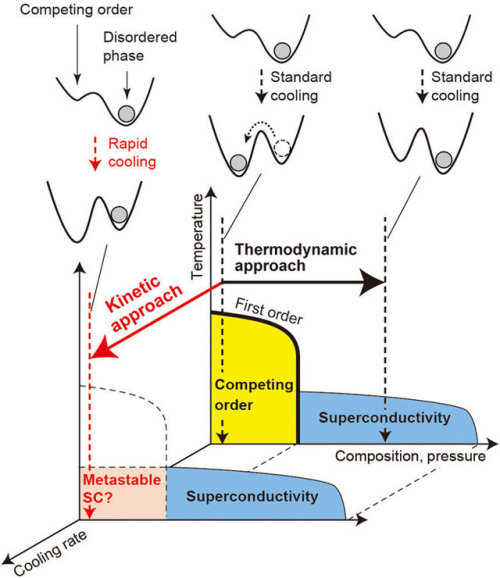

Forcing a metal to be a superconductor via rapid chilling

A team of researchers with the RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science and The University of Tokyo, both in Japan, has found a way to force a metal to be a superconductor by cooling it very quickly. In their paper published on the open access site, Science Advances, the group describes their process and how well it worked.

Scientists around the world continue to seek a material that behaves as a superconductor at room temperature—such a material would be extremely valuable because it would have zero electrical resistance. Because of that, it would not increase in heat as electricity passed through it, nor lose energy. Scientists have known that cooling some materials to very cold temperatures causes them to be superconductive. They have also known that some metals fail to do so because they enter a “competing state.” In this new effort, the researchers in Japan have found a way to get one such non-cooperative metal to enter a superconductive state anyway—and to stay that way for over a week.

Post link

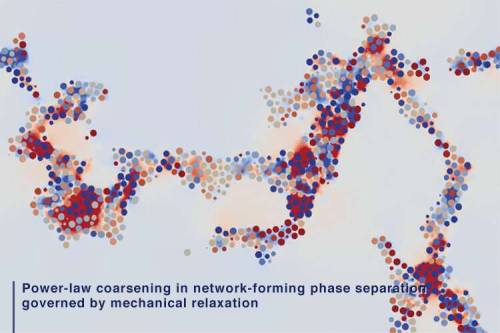

Discovery of a new law of phase separation

Researchers from Institute of Industrial Science at The University of Tokyo investigated the mechanism of phase separation into the two phases with very different particle mobilities using computer simulations. They found that slow dynamics of complex connected networks control the rate of demixing, which can assist in the design of new functional porous materials, like lithium-ion batteries.

According to the old adage, oil and water don’t mix. If you try to do it anyway, you will see the fascinating process of phase separation, in which the two immiscible liquids spontaneously “demix.” In this case, the minority phase always forms droplets. Contrary to this, the researchers found that if one phase has much slower dynamics than the other phase, even the minority phase form complex networks instead of droplets. For example, in phase separation of colloidal suspensions (or protein solutions), the colloid-rich (or protein-rich) phase with slow dynamics forms a space-spanning network structure. The network structure thickens and coarsens with time while having the remarkable property of looking similar over a range of length scales, so the individual parts resemble the whole.

Post link

Special nanotubes could improve solar power and imaging technology

Physicists have discovered a novel kind of nanotube that generates current in the presence of light. Devices such as optical sensors and infrared imaging chips are likely applications, which could be useful in fields such as automated transport and astronomy. In future, if the effect can be magnified and the technology scaled up, it could lead to high-efficiency solar power devices.

Working with an international team of physicists, University of Tokyo Professor Yoshihiro Iwasa was exploring possible functions of a special semiconductor nanotube when he had a lightbulb moment. He took this proverbial lightbulb (which was in reality a laser) and shone it on the nanotube to discover something enlightening. Certain wavelengths and intensities of light induced a current in the sample—this is called the photovoltaic effect. There are several photovoltaic materials, but the nature and behavior of this nanotube is cause for excitement.

“Essentially our research material generates electricity like solar panels, but in a different way,” said Iwasa. “Together with Dr. Yijin Zhang from the Max Planck Institute for Solid State Research in Germany, we demonstrated for the first time nanomaterials could overcome an obstacle that will soon limit current solar technology. For now solar panels are as good as they can be, but our technology could improve upon that.”

Post link

Electro-mechano-optical NMR detection

An international research project led by Kazuyuki Takeda of Kyoto University and Koji Usami of the University of Tokyo has developed a new method of light detection for nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) by up-converting NMR radio-frequency signals into optical signals.

This new detection method, appearing in the journal Optica, has the potential to provide more sensitive analysis compared with conventional NMR. Its possible utilization in higher-accuracy chemical analysis, as well as in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technology, are also of interest.

NMR is a branch of spectroscopy in which scientists measure the spin of an atom’s nucleus in order to determine its identity. Atomic nuclei subjected to a magnetic field induce radio-frequency signals in a detector circuit. Since different atoms cause signals at different frequencies, scientists can use this information to determine the compounds contained in a sample. The most well-known application of this is in MRI-based imagining, such as CT scans.

“NMR is a very powerful tool, but its measurements rely on amplification of electrical signals at radio-frequencies. That pulls in extra noise and limits the sensitivity of our measurements,” explains Takeda. “So we developed an experimental NMR system from scratch, which converts radio-frequency signals into optical ones.”

Post link

Having a ball: Crystallization in a sphere

Crystallization is the assembly of atoms or molecules into highly ordered solid crystals, which occurs in natural, biological, and artificial systems. However, crystallization in confined spaces, such as the formation of the protein shell of a virus, is poorly understood. Researchers are trying to control the structure of the final crystal formed in a confined space to obtain crystals with desired properties, which requires thorough knowledge of the crystallization process.

A research group at the Institute of Industrial Science, the University of Tokyo and Fudan University, led by Hajime Tanaka and Peng Tan, used a droplet of a colloid—a dispersion of liquid particles in another liquid, like milk—as a model for single atoms or molecules in a sphere. Unlike single atoms or molecules, which are too small to easily observe, the colloid particles were large enough to visualize using a microscope. This allowed the researchers to track the ordering of single particles in real time during crystallization.

“We visualized the organization process of colloid particles in numerous droplets under different conditions to provide a picture of the crystallization process in a sphere,” says Tan.

Post link