#ancientry

GIOVANNI BATTISTA TIEPOLO

ITALIAN, 1696–1770

THE CHARIOT OF AURORA

c. 1734

Oil on canvas

19 7/16 x 19 1/8 in. (49.3 x 48.6 cm)

The chariot of Aurora, goddess of the dawn, ascends into the sky to begin a new day. Sunflowers turn toward the light, while a bat flees with the darkness. A winged boy, or putto, awakens Aurora’s brother, the sun god Helios.

The broad brushstrokes and small scale of this canvas suggest that it was made as a sketch for a larger painting. Its subject matter would have been perfectly appropriate for the ceiling of a bedroom in an opulent eighteenth-century home.

From the Clark Institute Website.

Nymphs and Satyr

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, 1873, oil on canvas.

Inspired by a passage of Statius’ Silvae.

For forty years at the beginning of the 20th century, the painting was hidden away in storage because its buyer deemed it too provicative for public display.

THE WEDDING OF PELEUS AND THETIS

This month we’re going to take a look at Classical mythology and history and it’s reception in later art !!!

A scene super popular in Archiac Greek pottery, the subject of Joachim Anthonisz Wtewael’s painting The Wedding of Peleus and Thetis in 1612.

Check out the Clark art gallery for more info

Marble head of a Greek general

Roman, 1st–2nd century A.D., copy of a 4th C. Greek bronze.

NY Met. 24.97.32.

Post link

A selection of Graeco-Roman gems from the Penn Museum

29-128-939; 29-128-1867; 29-128-910; 29-128-2235; 29-128-2124; 29-128-1969; 29-128-2023; 29-128-2428; 29-128-2236.

Post link

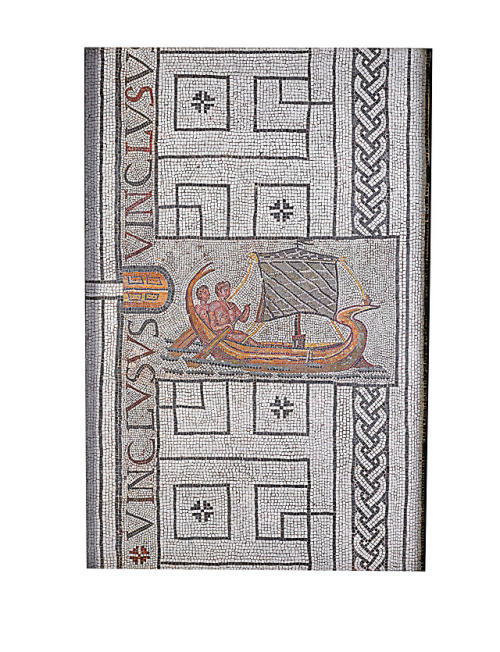

THESEUS ESCAPES THE LABYRINTH

c.200-250 AD

Tunisia, Zeugitana, Carthage

https://www.penn.museum/collections/object/340922

Post link

QUEEN PUABI’S HEADDRESS (2/2)

Ur, Iraq

c.2500 BCE

So many different displays, each rather telling…

“Her name and title are known from the short inscription on one of three cylinder seals found on her person. Although most women’s cylinder seals at the time would have read “wife of ___,” this seal made no mention of her husband. Instead, it gave her name and title as queen. The two cuneiform signs that compose her name were initially read as “Shub-ad” in Sumerian. Today, however, we think they should be read in Akkadian as “Pu-abi” (or, more correctly, “Pu-abum,” meaning “word of the Father”). Her title “eresh” (sometimes mistakenly read as “nin”) means “queen.”

In early Mesopotamia, women, even elite women, were generally described in relation to their husbands. For example, the inscription on the cylinder seal of the wife of the ruler of the city-state of Lagash (to the east of Ur) reads “Bara-namtara, wife of Lugal-anda, ruler of the city-state of Lagash.” The fact that Puabi is identified without the mention of her husband may indicate that she was queen in her own right. If so, she probably reigned prior to the time of the First Dynasty of Ur, whose first ruler is known from the Sumerian King List as Mesannepada. Inscribed artifacts from the Seal Impression Strata (SIS) layers above the royal tombs at Ur name Mesannepada, King of Kish, an honorific used by rulers claiming control over all of southern Mesopotamia.”

https://www.penn.museum/collections/highlights/neareast/puabi.php

Post link

Queen Paubi’s headdress (½)

c.2500 BCE

Ur, Iraq

“This ornate headdress and pair of earrings were found with the body of Queen Puabi in the Royal Cemetery at Ur. The headdress is made up of 20 gold leaves, two strings of lapis and carnelian, and a large gold comb. In addition, she wore chokers, necklaces, and large lunate-shaped earrings. Her upper body was covered by strands of beads made of precious metals and semiprecious stones that stretched from her shoulders to her belt. Ten rings decorated her fingers. A diadem or fillet made up of thousands of small lapis lazuli beads with gold pendants depicting plants and animals was apparently on a table near her head. Two attendants were in the chamber with Puabi, one crouched near her head, the other at her feet. Various metal, stone, and pottery vessels lay around the walls of the chamber.”

https://www.penn.museum/collections/highlights/neareast/puabi.php

Post link

RAM IN THE THICKET

Ur, Mesopotamia

c.2600-2500 BCE

“Sir Leonard Woolley dubbed this statuette the “ram caught in a thicket” as an allusion to the biblical story of Abraham sacrificing a ram. It actually depicts a markhor goat eating the leaves of a tree. One of two such objects excavated from The Great Death Pit at Ur, the other is housed at the British Museum. Little of the original Ram survived when Woolley excavated it, which he did by pouring wax on it and using waxed muslin strips to stabilize it. In Woolley’s original reconstruction of the Ram, he miscalculated the height of the animal and placed the tree too deeply into the base, causing the Ram’s legs to dangle above the tree’s branches.”

https://www.penn.museum/collections/highlights/neareast/ram.php

Post link

Jar with a Mistress of the Wild Animals

7th Century BCGreek, Cretan

http://carlos.digitalscholarship.emory.edu/items/show/8548

Post link