#funerary art

Cremation Chest (Cinerarium), Roman, A.D. 20-40 @thegetty

In the first century A.D., the dead were usually cremated rather than buried. Their ashes were placed in a marble cinerarium that was laid in a niche in the family tomb. The flower and bird motifs decorating this cinerarium symbolize fertility and rebirth. The name of the deceased would have been carved or painted on the rectangular panel, but this chest is not labeled. *

* museum label.

Post link

Effigy of His Eminence Cardinal Henry Beaufort (c. 1375 – 11 April 1447), Bishop of Winchester(1404), Bishop of Lincoln (1398) created Cardinal in 1426.

He served three times as Lord Chancellor and played an important role in English politics. He was a member of the royal House of Plantagenet, being the second son of the four legitimised children of John of Gaunt (third son of King Edward III) by his mistress (later wife) Katherine Swynford.

Post link

“Funerary altar of Iulia Victorina. Marble. Last quarter of the 1st century CE. The altar is dedicated to the en:manes of Iulia Victorina dead at 10 years and 5 months old. Purchase 1863. Louvre museum (Paris, France). Portrait on the front of the 10 year old girl at her death, garlanded in a floral frame, and on the back as the young matrona she would never become. Trees on each (side). Color by @chapps on twitter.

While Julia Victorina is only one child in the unhappy statistic that half of all Roman children died by the age of ten, her death in the last quarter of the 1st century CE is personalized by the unique and costly monument her parents set up in her memory. With this elegant altar, now in the Louvre Museum in Paris, Gaius Julius Saturninus and Lucilia Procula, who are otherwise unknown by rank, ancestry, or situation, memorialized their grief and hopes for a young daughter taken from them prematurely. The monument would have been placed in a family tomb and held a cinerary urn containing the child’s ashes. It is a rectangular block of white marble, elaborately carved on all four sides and crowned by a marble cover gracefully decorated with motifs (mouldings, volutes, and blossoms) that echo those carved on the front and back of the lower stone. The front of the altar bears the dedicatory inscription and features a portrait bust in high relief of the lovely face of a girl, framed by a wide border of acanthus leaves and variegated flowers, symbols in the Mediterranean world of eternal life. Julia Victorina, gazing pensively off to her right, wears ball-shaped pendent earrings, probably of gold; her shoulders are draped, her hair is styled almost boyishly and is crowned by a crescent moon, at once a symbol of eternity and association with Diana in her role as the moon-Goddess. On the back of the altar she appears again, similarly framed with botanicals, but now as a young matrona, as her parents had hoped in a few years to enjoy her; her face is solemn and thinner but recognizable as the child she was. She looks directly at the viewer, wearing the married woman’s stola, a palla draped over one shoulder and the same pendent earrings; her hair is arranged in a more matronly style, topped by a radiate crown that symbolizes her apotheosis in the heavens and her immortality. The short sides of the altar are decorated with a flourishing laurel tree, an evergreen sacred to Apollo, God of the sun; within its branches hover two birds, possibly ravens, his sacred bird, seen here together with laurel-crowned Apollo in his shrine. This extraordinary altar, with its portrait busts and floral designs promising immortality, offers moving testimony to the grief of Victorina’s parents over the loss of a beloved child.

The dedicatory inscription is crowded into the space below the child’s bust, which awkwardly divides the girl’s cognomen. The words are written in square capitals over five lines of diminishing size, with prominence given to the Di Manes and the girl’s name. The letters are well formed and centered, with medial dots (interpuncts) separating the words in lines 3-6.

Latin:

D[is] M[anibus]

IVLIAE VIC TORINAE

QVAE• VIX[it]• ANN[is] • X• MENS[ibus]• V•

C[aius]• IVLIVS• SATVRNINVS• ET

LVCILIA• PROCVLA• PARENTES

FILIAE• DVLCISSIMAE• FECERVNT

English:

To the spirits of the dead

Julia Victorina

Who lived for ten years and five months

Gaius Julius Saturninus and

Lucilia Procula

Parents of this sweetest daughter

Had this monument made

Notes to Funerary Inscription for Victorina:

Di Manes, m. pl.

the collective spirits of the dead, the divine spirits. DM is a common abbreviation for the dedication of a funerary monument to the spirits of the dead and thus is in the dative case. These letters or the words they stand for are regularly found at the head of funerary inscriptions dating from the end of the 1st century BCE through the 2nd century CE.

Iulia, -ae f.

Julia is the proper name of women born into the gens Iulia. Victorina appears to have inherited the nomen gentilicium from her father. The name of the deceased is either in the dative case as the dedicatee of the inscription, or the genitive as the possessor of the DM.

Victorina, -ae f.

The dead girl’s cognomen.

menses, menses m.

month. Both annis and mensibus are ablatives of time following vixit. Some inscriptions included days as well.

Saturninus, -i m.

The cognomen of Victorina’s father is found during the Republic and the Empire. There was a centurian named Gaius Iulius Saturninus who came from Chios and served under the Flavians in a unit of Spaniards in Egypt, but no firm connection can be made.

Lucilia, -ae f.

Lucilia is the proper name of women born into the gens Lucilia; Victorina’s mother’s cognomen is Procula.

parens, -entis m./f.

parent. It is in the nominative plural, in apposition with Saturninus and Procula, who are the subjects of the verb fecerunt.

dulcis, -e

sweet, lovely, dear, kind. The adjective is in the superlative degree. It modifies filiae; both are in the dative case, in apposition with Iuliae Victorinae.

[hoc monumentum]

this phrase normally follows the verb of dedication (fecit/fecerunt) in funerary inscriptions. Monumentum is the regular word for a Roman tombstone. Sometimes the entire formula is omitted as unnecessary or for lack of space or money.”

-taken from feminaeromanae, vroma, and wikipedia

More pictures and sources on my blog: https://paganimagevault.blogspot.com/2022/05/funerary-altar-of-iulia-victorina-1st-c.html

Old Kingdom of Egypt / Couple, probably Isi and his wife / 2300 BC

-

Raymond Mason / Le Voyage / 1966-2010

Post link

Ancient Worlds - BBC Two

Episode 6 “City of Man, City of God”

Palmyra was one of the most important cultural centres of the ancient world. Located in an oasis in the Syrian desert, it was a vital caravan stop for travellers crossing the desert. Palmyra grew steadily in importance as a city on the trade route linking Persia, India and China with the Roman Empire -it was made part of the Roman province of Syria in the mid-first century AD-. In 129, Palmyra was visited by emperor Hadrian, who granted it the status of a free city.

Palmyra exerted a decisive influence on the evolution of neoclassical architecture and modern urbanization, uniting the forms of Graeco-Roman art with indigenous elements and Persian influeces. Unique creations came into existence, notably in the domain of funerary sculpture.

Outside the ancient walls, along the four main access roads to the city, stood four cemeteries, Valley of the Tombs, which feature different types of tomb. The oldest and most distinctive group is represented by the funerary towers, tall multi-storey sandstone buildings belonging to the richest families. Some towers had four storeys and could accommodate up to 300 sarcophagi.

Valley of the Tombs, Palmyra -Tadmur- Syria

Post link

Ancient Worlds - BBC Two

Episode 2 “The Age of Iron”

“Lion Hunt dagger”. Bronze dagger inlaid with silver and gold from Mycenae.

The dagger is decorated with a scene depicting warriors with spears and shields fighting lions. It was found in Shaft Grave IVofGrave Circle A at Mycenae and it’s dated to the 16th century BC- Late Bronze Age.

Grave Circle A was part of a large cemetery outside Mycenae’s acropolis walls. It comprises six shaft graves, where nineteen bodies were buried. The wealth of the grave gifts reveals the high social rank of the deceased: gold jewelry and vases, gold death masks, decorated swords, bronze objects and artefacts made of imported materials like amber, lapis lazuli and ostrich eggs. The large number of weapons found shows that some of the dead were very good an important warriors. The site was excavated by the archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann in 1876.

The dagger was not used in actual warfare but held importance as decorative burial good for a powerful and wealthy Mycenaean citizen. The golden artwork on the dagger reflects Minoan influences like the introduction of animal figures, the delicate patterns and the shields of the hunters.

National Archaeological Museum of Athens, Athens, Greece

Post link

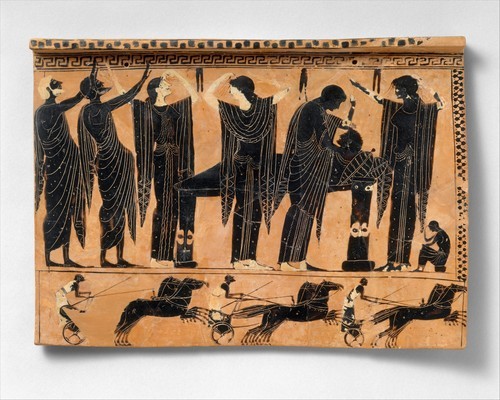

Ancient Worlds - BBC Two

Episode 3 “The Greek Thing”

A chariot driven by a charioteer. Terracota figurine. Votive offering from the 8th century BC on display at the Ancient Agora Museum ofAthens.

The Ancient Agora Museum is housed in the -reconstructed- Stoa of Attalos (a stoa was a covered portico) in the Agora of Athens, built c. 150 BC. The exhibition in the museum gallery holds archaeological finds from the ancient Agora. The collection of the museum includes clay, bronze and glass objects, sculptures, coins and inscriptions from the 7th to the 5th century BC. The earliest antiquities, potsherds, vases, terracotta figurines and weapons, dating from the Neolothic, Bronze Age, Iron Age and Geometric period, come from wells and tombs excavated in the area of the Athenian Agora and its surroundings.

Terracota figurines were a mode of artistic and religious expression, familiar objects to the ancient Greeks. Figurines are found in settlements, in graves and shrines. They stood in houses as mere decorations, or served as cult images in small house shrines. Some of them functioned as charms to ward off evil, others were brought to temples and sanctuaries as offerings to the gods and deposited in graves either as possessions of the deceased, gifts, or protective devices.

Ancient Agora Museum, Stoa of Attalos, Athens, Greece

Post link

Ancient Worlds - BBC Two

Episode 6 “City of Man, City of God”

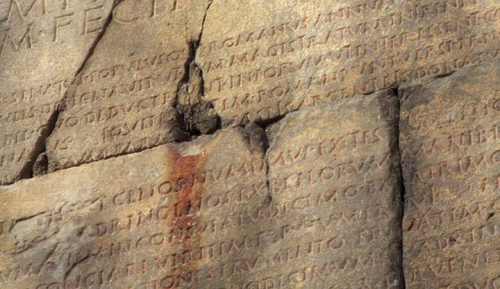

TheRes Gestae Divi Augusti, (The Deeds of the Divine Augustus) is the political testament, official autobiography and funerary inscription of the first Roman emperor, Augustus (63 BC – 14 AD

The text, written by Augustus himself, gives a first-person record of his life and accomplishments and tell us us how he wanted to be remembered. The work is very impersonal and selective; he doesn’t mention his failures, only his achievements. He wrote it as an Elogium (formal funerary oration) and as propaganda. Augustus may have intended it to be read out in the Senate after his death. In accordance with his wishes, it was inscribed on two bronze pillars in front of his mausoleum in Rome.

The achievements of the Divine Augustus were copied and inscribed on monuments throughout the empire. The best preserved version is on the Temple of Rome and Augustus in Ancyra, Galatia (modern Ankara, Turkey), known as the Monumentum Ancyranum.

Monumentum Ancyranum, Ankara, Turkey

Post link

I want you to understand how guilty I feel sometimes just for being alive.

I want to know what soldiers died who would have lived better lives than I have. I want to know what college students have surrendered and swallowed the pills and not been saved. I want to know what I can do to save them. I want to know if they want to be saved. I want to know if, for some suicides, death really is the better option, the path we would all choose in their situation, like euthanasia for the terminally ill, or a medieval traitor who chooses decapitation over being disemboweled.

I want to know what I ever did to deserve a good life.

FRAGMENTVMBecause

Ut intellegas quantum vivo me mihi misero interdum scelus sit; noscere milites mortuos qui probius me vixissent atque iuvenes qui mortem medicamine sibi consciverunt nec impediebantur; ego iam impedire hos si velint; scire quo tempore mors omnibus quaerenda sit, sicut aegri somnum vel ad asperrimas poenas damnati secuti feriri quam exinterari malvolunt; scire quae fecerim ut sim dignus beata vita volo.

Another exploration of Düsseldorf’s Nordfriedhof, in the twilight of the evening hour and short before rain set in. It’s becoming a habit and I keep being surprised by how much splendor and pomp but also food for thought this place has to offer. Some facts:

The graveyard is the closest nearby place, where I can enjoy a bit of calm and solitude in “nature”. There are wild parts, reminiscent of English landscape gardens, which occur quite magical to the senses. On the other hand, the majority of graves is fostered with an accuracy resembling that of miniature baroque gardens. The ballast bed trend is also taking over people’s last place of rest. There are exceptions, with lush planting gone wild, such as the grave covered in columbine, which is pictured above.

The caretakers seem to employ ecological concepts and care for biodiversity. E.g. I found an abandoned sandy part, previously covered in black nightshade, and now filled with fragrant phacelia, which is a soil conditioner and attracts a multitude of pollinating insects, not only honey bees. There are bee hives being implemented on this graveyard. There is a small pond visited by various water fowl as well grey herons and I spotted at least one large bird of prey, a common buzzard. The entrance on one side smells heavily like fox. There is a huge population of rabbits digging burrows all across the graveyard, which is probably not to the liking of all bereaved, but partly amusing to observe.

There is an abundance of large and impressive family gravesites as well as memorials for the victims of WWI and WWII. The annexed stonemason does an admirable job with the restoration of the historical gravesites.

It is easy to become enticed by the romanticism conveyed through the abundance and sheer beauty of the place and its funerary art. Yet I am also finding something oppressive or at least overwhelming about this. There is some money flowing into the maintenance of these graves, which are also a symbol of status and an ultimate expression of people’s egos. This in turn touches upon my own ego and leaves me behind with mixed feelings.

As much as I am occupied with the topic of death and the dead, I am part of a generation that will likely not enjoy the luxury of such post-mortem vanity. In truth, it has always been only a small part of humanity to take part in such luxury. Further, the fate of today’s youth is likely, to dissolve into spirit and not leaving much traces of physical existence behind. The larger mankind grows, the less space it will have for its exponentially growing amount of bodies. Neither are the monuments built over decades to last forever. However, they help to implement and strengthen the status of a few over a certain period.

Yet I keep returning to these places, which exhibit at least 2 centuries of opulent European grave culture, while caught in a dichotomy between the modern world and the past, between ego obsessions and spiritual ideals, between personal emotions and the need for detachment.

World Goth Day, Observation and Contemplation Another exploration of Düsseldorf’s Nordfriedhof, in the twilight of the evening hour and short before rain set in.Corinium Museum, Cirencester; Medieval Period

Wool Mark of John Fortey (d. 1459

From his brass in Northleach Parish Church

my notes;

Monumental brasses are a kind of memorial which grew in popularity during the 13th century, allowing detailed representations of the dead to be made for much less money than full stone or wooden effigies, which could be laid into the floors and therefore take up much less space. They were a favoured style of funerary art until the 16th century across Europe, the vast majority of these brasses survive in England (totalling around 4000). A great many of these are found in the eastern counties, although there is a large concentration of them around Cirencester, Northleach, and Lechlade.

Post link

Corinium Museum, Cirencester; Medieval Period

Replica brass of Reginald Spycer (d. 1442)

This depicts Spycer and his four wives, Margaret, Juliana, Margaret and his widow Joan, a vivid testimony to the mortality rate amongst women.

From Trinity Chapel, Cirencester Parish Church

my notes;

Monumental brasses are a kind of memorial which grew in popularity during the 13th century, allowing detailed representations of the dead to be made for much less money than full stone or wooden effigies, which could be laid into the floors and therefore take up much less space. They were a favoured style of funerary art until the 16th century across Europe, the vast majority of these brasses survive in England (totalling around 4000). A great many of these are found in the eastern counties, although there is a large concentration of them around Cirencester, Northleach, and Lechlade.

Post link