#palmyra

Ruins of Palmyra, Félix Ziem, 19th century.

The Central Bank of Syria “CBS” announced that it has released a new Syrian 5,000-pound banknote that went into circulation on Sunday 24th January, noting that the time has become suitable for that according to the current economic indicators.

A top quality Chocolate made by Patsy’s Candies, in existence since 1903, these Chocolates are sure to delight. In stock and moving fast, stop by the store at the Lebanon Valley Mall #cbd #cbdbenefits #cbdwellness #cbdmomlife #hemp #hemptodaynews #lebanon #lancaster #lebanonweekly #lebanontimes #lancasterpa #lancastercounty #harrisburgpa #manheimpa #elizabethtown #columbia #palmyra (at Lebanon Valley Mall)

https://www.instagram.com/p/CavrlhRspg5/?utm_medium=tumblr

Post link

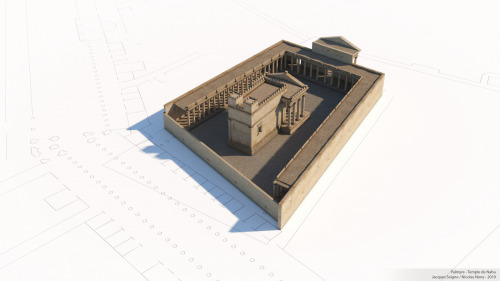

Temple of Bel (3D)

Palmyra (Tadmor),Syria

32 CE

Part I (exterior) || Part II (interior) || Part III (surrounding precinct)

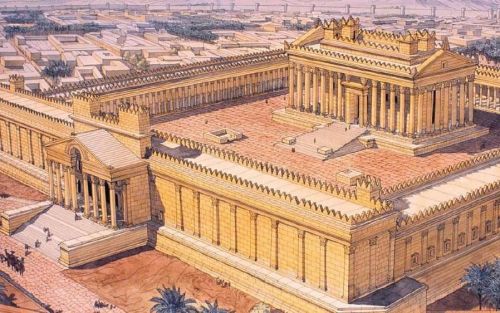

The Temple of Bel (Baal) was a temple located in Palmyra, and consecrated to the Mesopotamian god Bel, worshipped at Palmyra in triad with the lunar god Aglibol and the sun god Yarhibol, who together formed the center of religious life in Palmyra.

The temple was built on a tell with stratification indicating human occupation that goes back to the third millennium BCE. The area was occupied in pre-Roman periods with a former temple that is usually referred to as “the first temple of Bel” and “the Hellenistic temple”. The walls of the temenos and propylaea were constructed in the late first and the first half of the second century CE. The names of three Greeks who worked on the construction of the temple of Bel are known through inscriptions, including a probably Greek architect named Alexandras (Greek: Αλεξάνδρας). However, many Palmyrenes adopted Greco-Roman names and native citizens with the name Alexander are attested in the city.

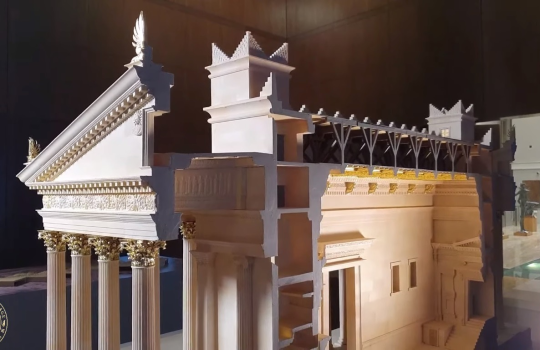

A discussion of its architectural features demonstrates both the plurality of artistic and architectural styles in the ancient Mediterranean, and the numerous cultures that frequently overlapped and inter-mixed there. Although an inscription attests to the temple’s dedication in 32 CE, its completion was gradual with major architectural elements added over the course of the first and second centuries.

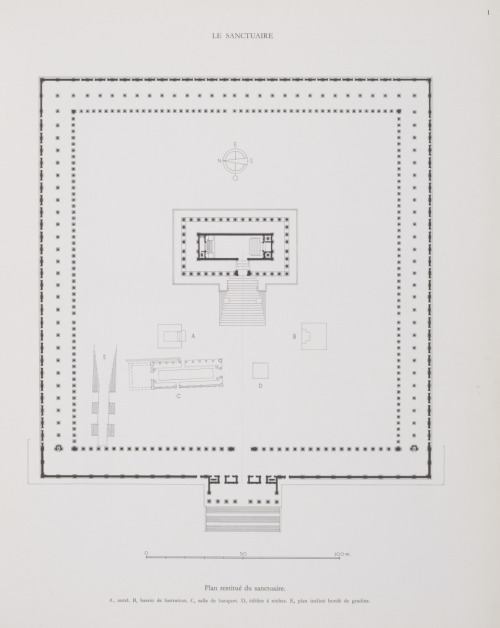

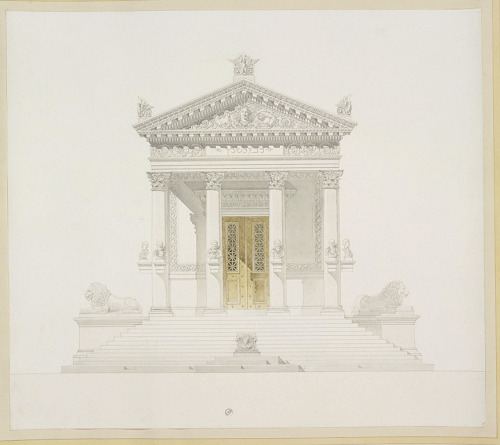

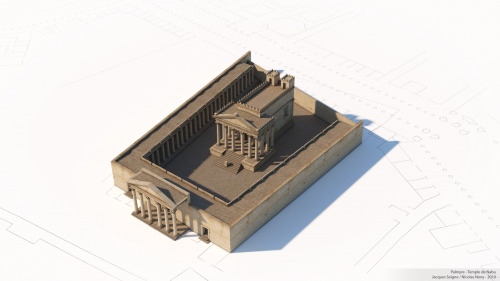

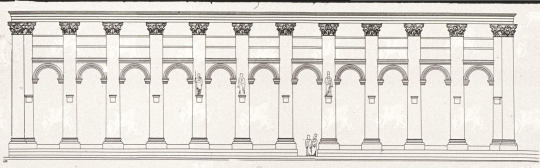

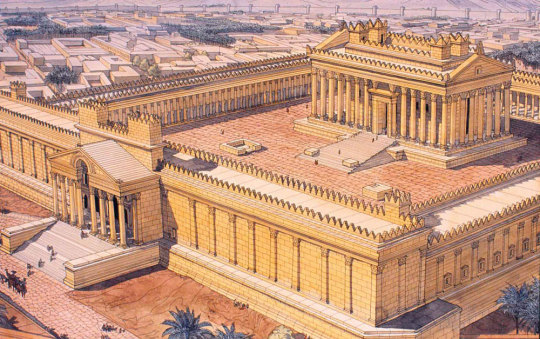

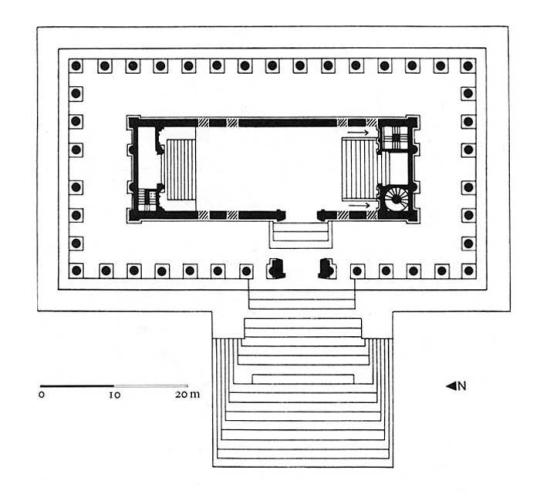

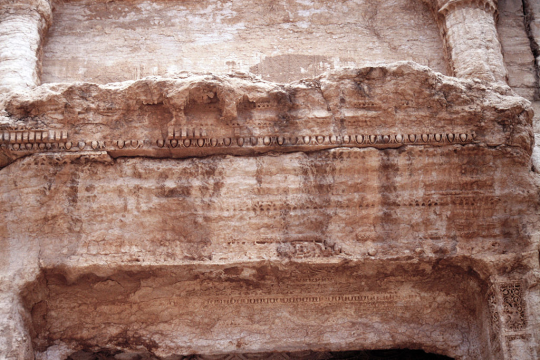

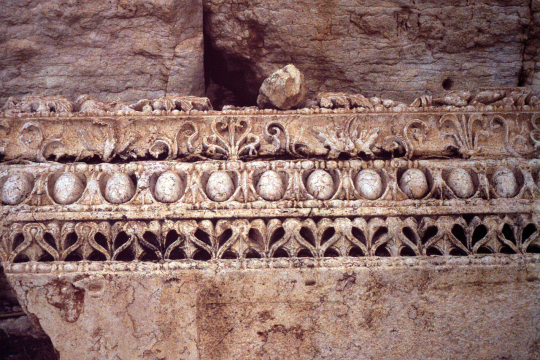

The organization of the temple’s ground plan derive from the traditions of eastern ritual architecture, including independent shrines for distinct divinities and, notably, the bent-axis approach to the cult (i.e. the architecture requires the celebrant to enter the temple and turn 90 degrees in order to view the offering table and cult area). The architectural elements employed in the temple’s elevation however, derive from the Graeco-Roman canon, including the use of the Corinthian order as well as various architectural elements of that adorn the frieze course and roofline .In its outward appearance, the temple seems to derive from the canon of Hellenistic Greek architecture .The temple itself sits within a bounded, architectural precinct measuring approximately 205 meters per side. This precinct, surrounded by a portico (a colonnaded entryway), encloses the temple of Bel as well as other cult buildings. The temple itself has a very deep foundation that supports a stepped platform. At the level of the stylobate (the platform atop the steps) the area measures 55 x 30 meters and the cella (the inner chamber of the temple that held the cult statue), stands over 14 meters in height and measures 39.45 x 13.86 meters.

Palmyra’s remarkable 2,000-year-old Temple of Bel was demolished in an atrocious crime against mankind and history in August 2015 by the Islamic militant group ISIS. (post-destruction 3D)

Fragments in the courtyard

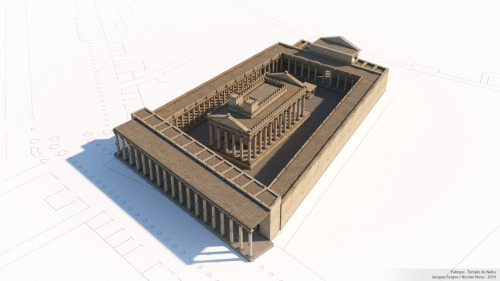

Temple of Bel (3D)

Palmyra (Tadmor), Syria

32 CE

Part I (exterior) || Part II(interior) || Part III (surrounding precinct)

The Temple of Bel (Baal) was a temple located in Palmyra and consecrated to the Mesopotamian god Bel, worshipped at Palmyra in a triad with the lunar god Aglibol and the sun god Yarhibol, who together formed the center of religious life in Palmyra.

A discussion of its architectural features demonstrates both the plurality of artistic and architectural styles in the ancient Mediterranean and the numerous cultures that frequently overlapped and inter-mixed there. Although an inscription attests to the temple’s dedication in 32 CE, its completion was gradual with major architectural elements added over the course of the first and second centuries.

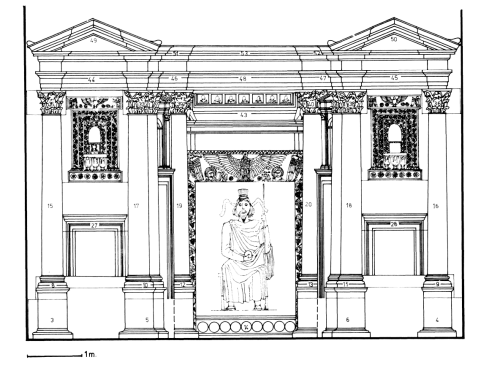

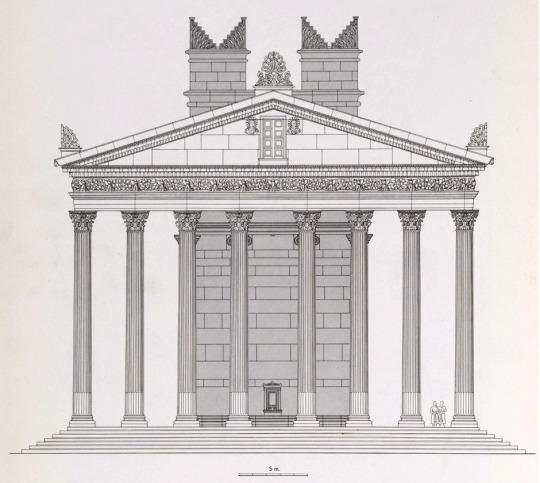

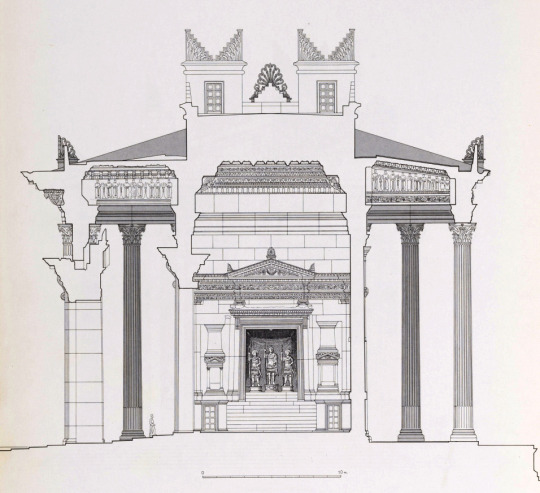

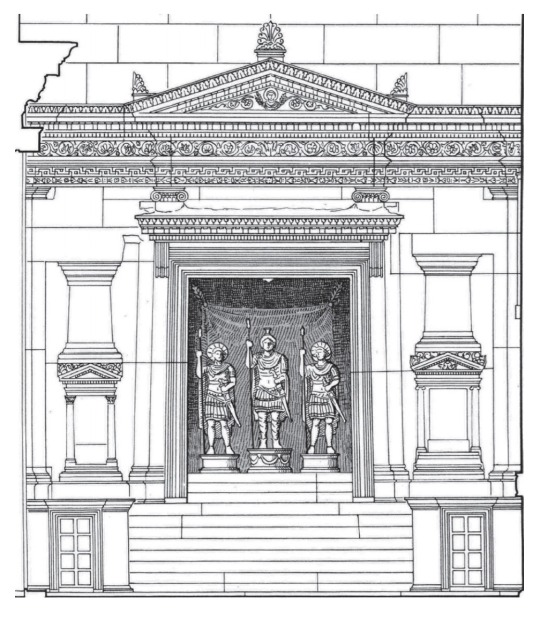

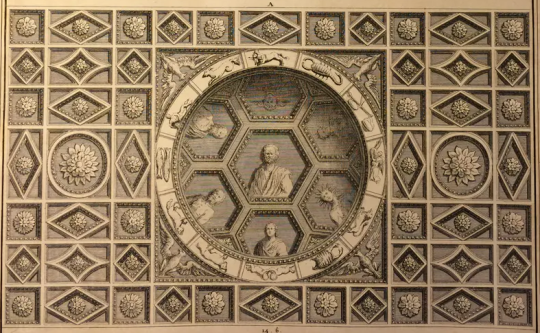

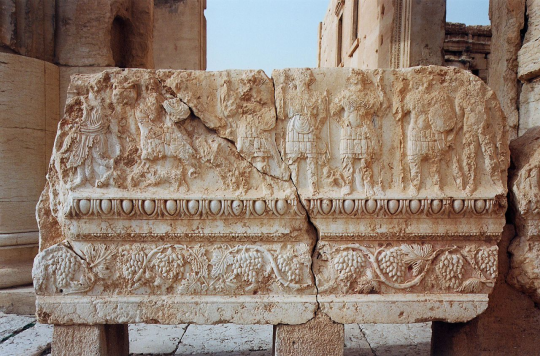

The cella is designed according to the Near Eastern tradition of the bent-axis approach and incorporates two separate shrines (thalamoi). A ramp and central stair, with an off-center doorway, grants access to the cella. The columnar arrangement is pseduoperipteral (free-standing columns at the porch with engaged columns on the sides and back) and includes an arrangement of 8 x 15 (height = 15.81 meters) fluted, Corinthian columns. The cella also has exterior Ionic half-columns at each of its ends. Merlons (crenellations) crowded the roof and the ceilings were coffered. From masons’ marks and graffiti found on the site, it seems that there were craftspeople of various background, including Greeks and Romans alongside the Palmyrenes.

Both the North and the South chambers had monolithic ceilings. The Northern chamber’s ceiling highlighted seven planets surrounded by twelve zodiac carvings as well as a camel procession, a veiled women, and what is believed to be Makkabel, the god of fertility.

Palmyra’s remarkable 2,000-year-old Temple of Bel was demolished in an atrocious crime against mankind and history in August 2015 by the Islamic militant group ISIS. (post-destruction 3D)

North adyton (3D)

South Adyton (3D)

Art

Temple of Bel (3D)

Palmyra (Tadmor), Syria

32 CE

Part I (exterior) || Part II (interior) || Part III (surrounding precinct)

The Temple of Bel (Baal) was a temple located in Palmyra, and consecrated to the Mesopotamian god Bel, worshipped at Palmyra in triad with the lunar god Aglibol and the sun god Yarhibol, who together formed the center of religious life in Palmyra.

The temple was built on a tell with stratification indicating human occupation that goes back to the third millennium BCE. The area was occupied in pre-Roman periods with a former temple that is usually referred to as “the first temple of Bel” and “the Hellenistic temple”. The walls of the temenos and propylaea were constructed in the late first and the first half of the second century CE. The names of three Greeks who worked on the construction of the temple of Bel are known through inscriptions, including a probably Greek architect named Alexandras (Greek: Αλεξάνδρας). However, many Palmyrenes adopted Greco-Roman names and native citizens with the name Alexander are attested in the city.

A discussion of its architectural features demonstrates both the plurality of artistic and architectural styles in the ancient Mediterranean, and the numerous cultures that frequently overlapped and inter-mixed there. Although an inscription attests to the temple’s dedication in 32 CE, its completion was gradual with major architectural elements added over the course of the first and second centuries.

The organization of the temple’s ground plan derive from the traditions of eastern ritual architecture, including independent shrines for distinct divinities and, notably, the bent-axis approach to the cult (i.e. the architecture requires the celebrant to enter the temple and turn 90 degrees in order to view the offering table and cult area). The architectural elements employed in the temple’s elevation however, derive from the Graeco-Roman canon, including the use of the Corinthian order as well as various architectural elements of that adorn the frieze course and roofline.In its outward appearance, the temple seems to derive from the canon of Hellenistic Greek architecture.The temple itself sits within a bounded, architectural precinct measuring approximately 205 meters per side. This precinct, surrounded by a portico (a colonnaded entryway), encloses the temple of Bel as well as other cult buildings. The temple itself has a very deep foundation that supports a stepped platform. At the level of the stylobate (the platform atop the steps) the area measures 55 x 30 meters and the cella (the inner chamber of the temple that held the cult statue), stands over 14 meters in height and measures 39.45 x 13.86 meters.

The cella was lit by two pairs of windows cut high in the two long walls. In three corners of the building stairwells could be found that led up to rooftop terraces. In the court there were the remains of a basin, an altar, a dining hall, and a building with niches. And in the northwest corner lay a ramp along which sacrificial animals were led into the temple area. There were three monumental gateways, of which the entry was through the west gate.

Palmyra’s remarkable 2,000-year-old Temple of Bel was demolished in an atrocious crime against mankind and history in August 2015 by the Islamic militant group ISIS. (post-destruction 3D)

Main gate

North side

Art from the sanctuary

Post link

Temple of Ba’al Shamin

Palmyra (Tadmor), Syria

131 CE

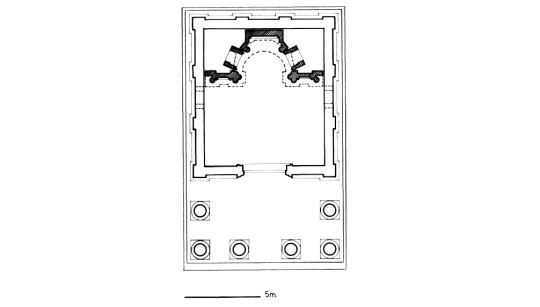

The temple of Baalshamin was a prostyle (having free standing columns on the façade only), tetrastyle (four columns across the façade) temple of the Corinthian order with a deep porch (visible in the photo below). As with other Palmyrene architecture, the sanctuary of Baalshamin demonstrated hybridity of design—incorporating both Near Eastern and Graeco-Roman elements.

The temple was set within a colonnaded precinct. The temple building dated to c. 130 CE with its altar was built in 115 CE and represents an addition to a sanctuary that already existed by 17 CE. The temple itself is conventional in its external design, meaning it conforms to what one would expect from a Classical Graeco-Roman structure. The four freestanding columns across the façade are complemented by engaged pilasters at the sides and back.

The temple’s cult is dedicated to Baalshamin or Ba'al Šamem, a northwest Semitic divinity. The name Baalshamin is applied to various divinities at different periods in time, but most often to Hadad, also known simply as Ba’al. Along with Bel, Baalshamin was one of the two main divinities of pre-Islamic Palmyra in Syria and was a sky god.

The colonnaded precinct experienced several phases of development during the first century CE. (prior to the addition of the current temple). By the time of the temple’s construction, the colonnade had become a so-called Rhodian peristyle—meaning one flank was taller than the other three. The complex continued to develop across the course of the second century.The temple itself adopts a Near Eastern motif of including a window in each of the cella’s flanks, a trait that is not Graeco-Roman but that finds comparison in contemporary temples in Lebanon. These windows reflect the belief that the divinity dwelled in the temple.

The temple was originally a part of an extensive precinct of three courtyards and represented a fusion of ancient Syrian and Roman architectural styles. The temple’s proportions and the capitals of its columns were Roman in inspiration, while the elements above the architrave and the side windows followed the Syrian tradition. The highly stylized acanthus patterns of the Corinthian orders also indicated an Egyptian influence. The temple had a six-column pronaos with traces of corbels and an interior which was modelled on the classical cella. The side walls were decorated with pilasters.

The temple would have been closed during the persecution of pagans in the late Roman Empire in a campaign against the temples of the East made by Maternus Cynegius, Praetorian Prefect of Oriens, between 25 May 385 to 19 March 388. With the spreading of Christianity in the region in the 5th century CE, the temple was converted to a church.

Post link

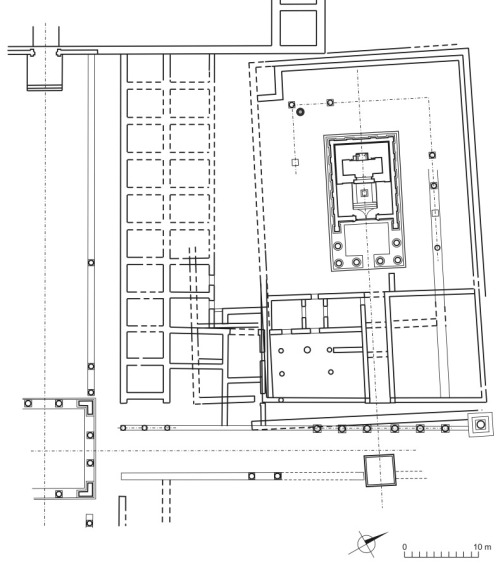

Temple of Nabu

Palmyra (Tadmor), Syria

2nd century CE

The temple was a Corinthian Hexastyle Peripteral temple dedicated to Mesopotamian god of wisdom and writing, and was Eastern in its plan; the outer enclosure’s propylaea led to a 20-by-9-metre podium through a portico of which the bases of the columns survives. The peristyle cella opened onto an outdoor altar.

The temple is characterized by its eastern style and architectural and cultural features which still exist at the site, according to Assaf.

He clarified that there are three entrances towards the long street and a main entrance in the southern side, surrounded by corridors and columns with Corinthian crowns with decorations on either side and three rooms directly connected to the inner hallway, which leads to a courtyard with a temple in center.

Post link

Temple of Allat

Palmyra (Tadmor), Syria

1st century CE

The sanctuary of Allat included a temple which is clearly younger than the temenos itself. The same is true of the temple of Ba῾alshamin, and the two are very similar to each other, even if that of Allat is preserved only in its lower courses. Both are prostyle of Roman type with a Corinthian porch of four columns in front and two intercolumnia deep, facing East, both are articulated on three other sides with pilasters, both stand on low podiums and had plain pediments in front and back.

The Lion of Al-lāt is statue that adorned the Temple, of a lion holding a crouching gazelle, was made from limestone ashlars in the early first century CE and measured 3.5 m (11 ft) in height, weighing 15 tonnes. The lion was regarded as the consort of Al-lāt. The gazelle symbolized Al-lāt’s tender and loving traits, as bloodshed was not permitted under penalty of Al-lāt’s retaliation. The lion’s left paw had a partially damaged Palmyrene inscription which reads: tbrk ʾ[lt] (Al-lāt will bless) mn dy lʾyšd (whoever will not shed) dm ʿl ḥgbʾ (blood in the sanctuary).

The temple of Allat can be dated from the internal evidence of two incomplete inscriptions as having been built in CE 148 or slightly later, barely twenty years or so after the cella of Ba῾alshamin. It is also clear that the same families were involved in the two sanctuaries. The fragmentary text from the doorway of Allat mentions two buildings: “this naos” and “the old hamana”. The latter term is Aramaic and applies to some sort of shrine. Here, for the first time, it can be ascribed with practical certainty to material remains.

These remains consist of the foundations of a small rectangular building, broader than it is deep (7.35 through 5.50 m), with very thick walls around a narrow room, barely large enough for the door wings to open inwards. This shrine has been piously preserved within the second century temple in such a way that the new walls enclose the old, leaving between them a space averaging only 6 cm wide. Stone of a different kind was used in each case. As the floor of the old building was laid practically on the ancient ground level, and as it continued to be used, the internal level of the new temple was lower than expected: the front columns set on a bench around the porch and the floor of the cella a few steps down from the porch.

The foundations of the new building also go deeper into the ground, which would have been no easy affair: they would have had to undermine the old shrine partly while keeping it intact at all costs. The cella is thus nothing more than a box containing the ancient tabernacle which remained in use as the adyton, the inner sanctum and seat of the goddess. This is apparently the only known case of such survival in Syria: usually, the adyton is built together with the temple, even if it may take the aspect of an independent building, as the two adytons of Bel, or incorporate some elements taken from the older phase, as in the case of Ba῾alshamin.

The exterior changed radically and became Classical in inspiration, Hellenistic for Bel, Vitruvian for the other two. In each case, however, these Corinthian temples were meant to impress the viewer and proclaim their belonging to the modern Roman world, but they were just a disguise. All three keep in different ways the memory of smaller, simpler tabernacles dedicated to the same godheads in the same places, but only the temple of Allat actually preserved its predecessor intact.

As the hamana of Allat remained complete, it would be pointless to roof the new cella above it. Indeed, there are good reasons to believe that the place was left open: not only has an outlet been arranged for rainwater, but more importantly, the pre-existing altar was left in front of the tabernacle but inside the temple, standing on a stone pavement not linked to either building; it could be used only if open to the sky. On the other hand, the porch should have been covered in the normal way. The narrow room inside the primitive shrine could not have any windows, as its walls are over 2 m thick. It was closed with two-winged doors which, when opened, revealed a statue inside a niche.

We have recovered several fragments of the framing, consisting of jambs covered with vine-scrolls and of a lintel featuring a spread eagle. The slab on which the statue was placed is preserved in place and bears a series of grooves and mortises suggesting a graphic restoration. This is possible thanks to several small replicas of the enthroned goddess, seated between two lions and holding a long sceptre. The statue was probably not of one piece but composite, and could perhaps have been moved from the throne to be carried in processions.

This is in sharp contrast to rituals that we can envisage for the relief images of other temples. But then, the idol of Allat was much older than the appearance of frontality in the art of Palmyra, and with it the possibility to represent the gods on a flat surface offered for viewing and veneration in other temples. Dated monuments allow us to fix the advent of frontality in the brackets between 15 and 30 CE. For its part, the idol of Allat (called “Lady of the House”), was offered by a certain Mattanai, being an ancestor of someone who mentioned the fact five generations later in 115 CE. This would bring back the original foundation to about 50 BCE at the latest (Gawlikowski 1990: 101–108).

By the same token, the first shrine of Allat becomes the oldest known in Palmyra and the first of which some remains are still in place. Another inscription found nearby mentions a hamana built in 31/30 BCE for the solar god Shamash. A square foundation 4 m to the side is still to be seen there, exactly on the axis of the Allat temple. It could have once contained a small inner room and the inscription could once have been placed in its wall, though we cannot establish this with absolute certainty. Another similar foundation was found a few years ago very close to the Allat temple. Possibly, the original temenos contained several such chapels, each for a different god. The Vitruvian cella had intruded in its midst about 150 CE without changing the character of the cult and scrupulously keeping the old installations in place.

The temple of Allat was destroyed twice: it was sacked once in 272 by the Roman troops of the emperor Aurelian and again, definitely, by a Christian mob at the end of the fourth century. In the meantime, the sanctuary remained in use within the limits of a legionary camp for over a century. One may imagine that access to it was restricted as far as the civilian population was concerned. The temple’s interior was radically changed during this time. Indeed, the old tabernacle contained within the cella had been destroyed together with the statue on the first occasion, while the walls of the cella seem to have remained intact.

At any rate, a restoration effort occurred very soon afterwards. Instead of trying to rebuild the shrine, its foundations were left in place and covered with a kind of platform including some sculptured fragments, which were thus piously preserved. We could recover some votive reliefs of the first to third centuries and some elements of the niche once framing the seated statue of the goddess. The cult image itself had to be replaced. Four short columns were brought in and set up in front of the masonry preserving the broken remains to support roofing in the form of a square canopy or perhaps a shelter from wall to wall over the whole ruin of the primitive shrine.

Under the canopy a new statue was fixed. Fallen and broken during the second sack, it has survived for the most part and could be reassembled. The statue is a second century copy of a statue of Athena, executed in Pentelic marble. It is clear that the original was Athenian and conceived in the circle of Pheidias. It has replaced an old and venerable, but no doubt primitive statue, and this in a time right after a military disaster and economic collapse. It could hardly be imported from Greece in these conditions, but could rather have embellished some profane public building in the city before receiving divine honours in the restored temple. The late restoration was probably an initiative of a Roman legionary legate under Aurelian, who wanted to reconcile the destitute local goddess, seeing in her no doubt Minerva, one of the standard Roman army cults. If so, the statue does not provide evidence for the cult of Allat, but is rather one of a series of Classical marbles imported to Palmyra for adornment of public buildings.

Post link

- Heard of Mars,Roman2nd century C.E. marble

- Head of ManCypriot5th century B.C.E.

- Tomb portrait of Tiklak, daughter of Aphshi, Palmyra, Syria, inscription in Palmyrene Aramaic, 3rd century C.E.

Post link

The Pitfalls of “Charismatic Archaeology” - Part One: What’s in a Name?

All right, as promised, we’re going to take a look at the phenomenon of “charismatic archaeology” (Munawar 2017, 41) as it applies to the so-called Arch of Triumph in Palmyra, which was destroyed by Islamic State militants in 2015 and whose modern cultural context has seemingly superseded its archaeological context in the years since. Because there’s a lot to go over here, I’m going to have to split this up into a few parts. But the main takeaway of this series is that this arch—or tripylon—is still fascinating, even if it isn’t necessarily as ‘Roman’ as we are led to believe and that branding it as such does a disservice to the local Palmyrene builders responsible for its innovative construction in the late second to early third centuries AD (but more on that in later installments).

We already encounter an issue with the classification of this monument as a triumphal arch. Once it was torn down by the Islamic State in October 2015, the tripylon was introduced to the public on a global scale. In their reporting, numerous international news outlets used this term to describe the structure. However, this inaccurate classification pre-dates the arch’s destruction: my thesis advisor told me that when she last visited Palmyra in 2005, the archaeological park guided tourists to the monument and the adjacent section of the city’s Great Colonnade with a sign that read “Triumph Arc (sic) and the Long Street.” That said, the vast majority of the archaeological literature that was written prior to 2015 more accurately designates it as simply a monumental arch or, more commonly in the German-speaking world, a tripylon.

Other common misattributions the monumental arch is given are those of “Hadrian’s Arch/Gate” and the “Arch of Septimius Severus,” though the former is more often a fixture in the German-speaking world (where it’s called the Hadrian BogenorHadrianstor). In AD 129/130, Hadrian did himself travel to Palmyra, and during his stay, he granted the city his name (Hadriana Palmyra; Browning 1979, 27). And while it is true that there was an uptick in monumental civic construction and ‘Romanization’ in the city afterwards, the tripylon had not begun to be built until roughly the late Antonine period, around AD 175/180 (Barański 1995, Fig. 1; Tabaczek 2001, 128), so it could not have feasibly been built for Hadrian (in contrast to Hadrian’s Arch in Gerasa, Jordan). Similarly, this start date places its chronology too early to have been built for Septimius Severus, either, as his reign lasted from AD 193–211. That said, a number of scholars do date its construction to his reign or to post-212 more broadly (e.g. Browning 1979, 88; Burns 2017, 245; or Will 1983, 74). However, in doing so, they fail to take into consideration that a structure as large and complicated as the tripylon (more on that later) would have taken years and years to complete, and it was most likely finished sometime in the late Severan period (Tabaczek 2001, 38. 130). Therefore, any commemorative/honorific purpose for this arch is called into question (though statues to Odenathus and his family were placed in niches in the central passageway well after its initial construction in the mid-late 3rd century AD; Burns 2017, 245).

The monument’s designation as a ‘triumphal’ arch or the Arch of Hadrian/Septimius Severus immediately brings it firmly into the realm of ‘Roman’ archaeology, but naming it as such ignores the tripylon’s indigenous Palmyrene context, which in itself tells a much richer story than its apparent association with the Roman Empire. It should be stressed that the term ‘triumphal arch’ was seldom used in antiquity (Cassibry 2018, 246) and that scholars from over a century ago had even expressed the need to use caution when defining these monuments as such (Densmore Curtis 1908, 27). Not only does this term signal the ‘Romanness’ of these structures, but it tends to evoke a sense of particular importance or gravitas to the modern layperson on account of how modern Western powers have adapted the architectural form and used it to express their own “cultural statement,” whether at home or abroad in colonized territories (e.g. the Arc de Triomphe in Paris or the Gateway of India in Mumbai; Ball 2016, 286).

In reality, the eastern Roman territories of Syria and Provincia Arabia have no known ‘true’ triumphal arches, such as those that we’d associate with the city of Rome itself (e.g. the Arch of Septimius Severus or the Arch of Constantine; Ball 2016, 286), but there are three known commemorative/honorific arches to the emperors Trajan (Dura Europos) and Hadrian (Jerusalem and Gerasa; Segal 1997, 131). The point of such monuments was to serve as imperial propaganda “in Wort und Bild” (“in word and image”; Kader 1996, 184). As we will see in later parts of this series, this was not necessarily the case where Palmyra’s tripylon is concerned.

Speaking of cultural statements and propaganda, it is also possible that the concept of triumph was used to the advantage of the Institute for Digital Archaeology of Oxford and Harvard Universities when it decided to use digital methodologies to create a physical reconstruction of the tripylon in 2016 (and believe me, there will be an entire separate post about everything that was wrong with this replica). The IDA’s branding of the tripylon as such in the wake of the Islamic State’s retreat from Palmyra may have delivered a different kind of political message in the sense that the arch and its subsequent reconstruction could represent a triumph of the Syrian people and their cultural heritage over the militants and their wanton destruction of it—perhaps as a 21st-century parallel to Zenobia’s liberation of Palmyra from the Roman Empire (Munawar 2019, 152). Whatever the reason, the emphasis on the monument’s charismatic ‘triumphal’ nature obfuscates its ancient urbanistic context, which will be discussed more in detail in the next part of this series.

Thanks for reading!

Works Cited:

W. Ball, Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire, 2nd Edition (London 2016).M. Barański, The Great Colonnade of Palmyra Reconsidered, Aram Periodical 7(1), 1995, 37–46.

R. Burns, Origins of the Colonnaded Streets in the Cities of the Roman East (Oxford 2017).

I. Browning, Palmyra (Park Ridge 1979).

K. Cassibry, Reception of the Roman Arch Monument, AJA 122 (2), 2018, 245–275.

C. Densmore Curtis, Roman Monumental Arches (New York 1908).

I. Kader, Propylon und Bogentor. Untersuchungen zum Tetrapylon von Latakia und anderen frühkaiserzeitlichen Bogenmonumenten im Nahen Osten (Mainz am Rhein 1996).

N. Munawar, Reconstructing Cultural Heritage in Conflict Zones: Should Palmyra be Rebuilt?, EX NOVO Journal of Archaeology 2, 2017, 33–48.

N. Munawar, Competing Heritage: Curating the Post-Conflict Heritage of Roman Syria, Bulletin - Institute of Classical Studies 62(1), 2019, 142–165.

A. Segal, From Function to Monument: Urban Landscapes of Roman Palestine, Syria and Provincia Arabia (Oxford 1997).

M. Tabaczek, Zwischen Stoa und Suq. Die Säulenstraßen im Vorderen Orient in römischer Zeit unter besonderer Berücksichtigung von Palmyra (Diss. University of Cologne 2001).

E. Will, Le développement urbain de Palmyre, Syria 60, 1983, 69–81.

Image Source: x (the first is from a PowerPoint I presentation I gave in January)

Post link

Ancient Worlds - BBC Two

Episode 6 “City of Man, City of God”

Palmyra2010

Part II

Palmyra, Syria

Post link

Ancient Worlds - BBC Two

Episode 6 “City of Man, City of God”

Palmyra2010

Part I

Palmyra, Syria

Post link

Ancient Worlds - BBC Two

Episode 6 “City of Man, City of God”

Palmyra was one of the most important cultural centres of the ancient world. Located in an oasis in the Syrian desert, it was a vital caravan stop for travellers crossing the desert. Palmyra grew steadily in importance as a city on the trade route linking Persia, India and China with the Roman Empire -it was made part of the Roman province of Syria in the mid-first century AD-. In 129, Palmyra was visited by emperor Hadrian, who granted it the status of a free city.

Palmyra exerted a decisive influence on the evolution of neoclassical architecture and modern urbanization, uniting the forms of Graeco-Roman art with indigenous elements and Persian influeces. Unique creations came into existence, notably in the domain of funerary sculpture.

Outside the ancient walls, along the four main access roads to the city, stood four cemeteries, Valley of the Tombs, which feature different types of tomb. The oldest and most distinctive group is represented by the funerary towers, tall multi-storey sandstone buildings belonging to the richest families. Some towers had four storeys and could accommodate up to 300 sarcophagi.

Valley of the Tombs, Palmyra -Tadmur- Syria

Post link

Gavin Hamilton, Wood and Dawkins Discovering Palmyra.

Oil on canvas, 310 × 389 cm (10 ft 2 in × 12 ft 9 in).

National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Post link

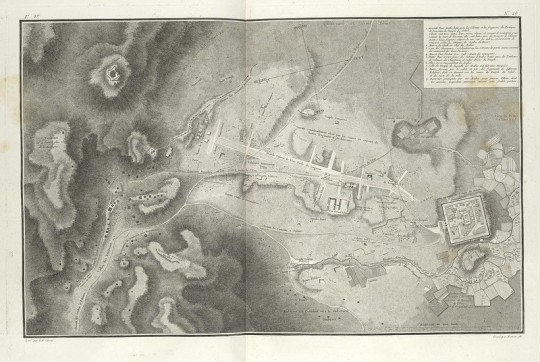

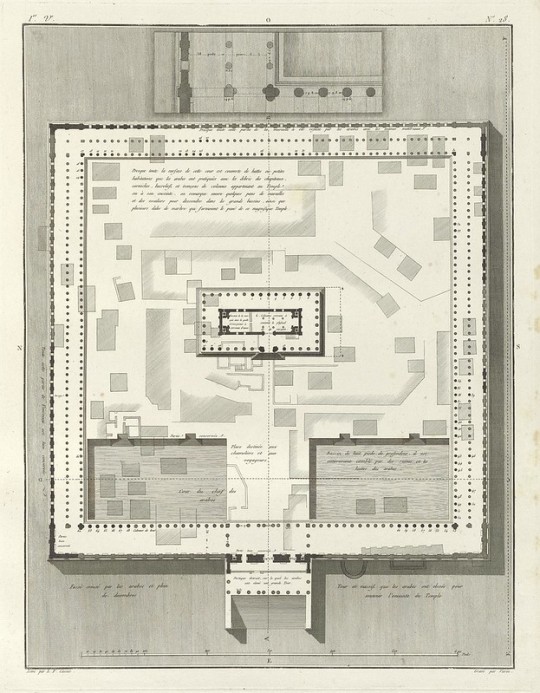

Three plates from Robert Wood’s The Ruins of Palmyra, Otherwise Tedmor, in the Desart (London, 1753).

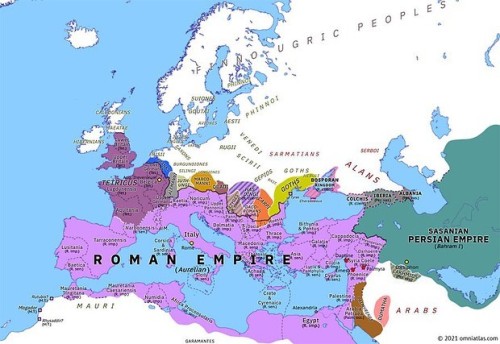

NEW MAP: Europe 273: Revolt of Firmus (July 273) https://buff.ly/3ete3vW No sooner had Aurelian crossed into Europe after his defeat of Zenobia, than Palmyra rebelled again. Racing back east, the emperor sacked the city in retribution, only to face a pro-Palmyrene uprising in Egypt. This too Aurelian crushed, although in the fighting the Brucheion quarter of Alexandria, which housed the famous Great Library, was almost entirely destroyed. #thirdcentury #ancientrome #romanegypt #ancientegypt #aurelian #cartography #dacia #europe #europeanhistory #historia #historian #historic #historylesson #historylover #historymaker #historymatters #spqr #classicalera #map #mapping #maps #alexandria #palmyra #roman #romanempire #romanhistory #romans #romansyria #greatlibrary #newmap (at Alexandria, Egypt)

https://www.instagram.com/p/CMT2eArgY9b/?igshid=fcuqbsbqgn9k

Post link

NEW MAP: Europe 272: Downfall of Zenobia (summer 272) https://buff.ly/3c7Cv30 After his victory at Immae, Aurelian marched south and decisively defeated the Palmyrenes at Emesa. Zenobia fled to Palmyra, but was captured, along with her city, by Aurelian in late summer 272. Roman rule in the East had been restored. #thirdcentury #3rdcentury #ancientrome #aurelian #zenobia #cartographer #europe #europeanhistory #heritage #historian #histories #historyclass #historydegree #historyfacts #historyinthemaking #historylesson #historymuseum #historynerd #persianempire #maps #palmyra #phoenicia #spqr #roman #romanempire #romanhistory #romans #ancientsyria #teachinghistory #newmap (at Palmyra, Syria)

https://www.instagram.com/p/CMB15OzgCX1/?igshid=ernlowt3se19

Post link

NEW MAP: Europe 272: Battle of Immae (spring 272) https://buff.ly/2NHTXD1 While traveling east to face Zenobia, Aurelian concluded that Dacia was indefensible and pulled the remaining legions from that province south of the Danube. He then crossed into Asia Minor in early 272 and, marching rapidly on Syria, defeated Zenobia at Immae a few months later. #3rdcentury #ancientrome #cappadocia #dacia #europe #europeanhistory #galatia #historic #historisch #history #historybuff #historydegree #historyschool #maps #aurelian #moesia #oldmaps #palmyra #spqr #roman #romancivilwar #romancivilwars #romanempire #romanhistory #imperialrome #romans #romansyria #palmyra #zenobia #newmap (at Antakya, Hatay)

https://www.instagram.com/p/CLv31MUAeMK/?igshid=16j6ckzw7ajzv

Post link