#medieval europe

~ Aquamanile in the Form of a Rooster.

Date: 13th century

Place of origin: Lower Saxony, Germany

Medium: Copper alloy

Today, I’m making a quick and easy accompaniment to any medieval Irish meals you have planned - a bowl of praiseach (pronounced: prashock)! The basis of this is a simple savour porridge, that’s then flavoured with some sautéed mustard greens! Although wild mustard (charlock) greens are usually used, any suitably pungent edible greens can be used!

In any case, let’s now take a look at The World That Was! Follow along with my YouTube video, above!

Ingredients (for 4 portions)

Mustard Greens / Turnip Greens

2 cups oatmeal (or oat groats)

2 cups milk (or water)

butter

Method

1 - Prepare the Greens

To begin with, we need to chop some greens. Though praiseach is normally made using wild mustard (charlock), you can also use normal mustard greens, or even turnip greens (like I’m using here). They all have similar taste profiles - being pungent, slightly spicy greens - that react similarly when being cooked.

In any case, chop your greens finely, removing any untoward-looking leaves that escaped your prep-work.

2 - Sautee the Greens

When your greens of choice have been chopped to your liking, toss a knob of Irish butter into a pan, and let it melt. You can of course use local butter, I’m just totally not biased. When the butter has melted, toss in your chopped greens, and let everything sauté away over a medium heat for only a couple of minutes. Your greens may shrivel up, but this is normal! Take them off the heat when they’ve been coated in butter, and are lovely and fragrant.

3 - Prepare Praiseach

When your greens are cooling off, go start making your porridge base. Toss equal parts of oats and water (or milk, if you want to be fancy) into a pot, and place this over a medium-high heat. Keep stirring this so it doesn’t stick to the bottom of your pot.

While I used rolled oats here, which may have had a similar analogue in antiquity, whole oat groats would have been more commonly used (i.e. the whole, unhusked grains themselves, as opposed to the modern rolled, husked, and crushed grains used here). This would have had a higher fibre content than this dish.

When your oats have been cooked, but are still about 10 minutes from being served, toss in your cooked greens. Stir all of this together, and let it infuse for ten more minutes.

Serve up warm, in a bowl of your choice, and dig in!

The finished dish is quite thin and easy-going. It’s not overly flavourful, but has a nice background heat thanks to the mustard greens. By sautéing them, you cut the edge off the taste, and let it mellow out among the oats.

Oats are a wild grain, and can be grown in relatively poor-quality soils - such as those in parts of the midlands and west of Ireland - and as a result were seen as a “peasant grain” for much of the medieval period. Porridge is one of these peasant dishes that persist into the modern day, as it’s still a simple yet filling dish that can be altered with the addition of different ingredients!

This week, I’m going to be recreating a simple carrot and coriander soup that was popular in medieval French cuisine - the simple Potage de Crécy. Although I’m using orange carrots, which were rare in antiquity, carrots, parsnips, or any combination of these would work well here!

In any case, let’s now take a look at The World That Was! Follow along with my YouTube video, above! Check out my Patreon for some more recipes!

Ingredients (for 2-3 portions)

1 onion (or an equal volume to the amount of carrots) chopped

3 carrots (or an equal volume to the amount of onions) diced

2 cloves garlic

olive oil

ground coriander

500ml stock (e.g. chicken, vegetable, etc.)

Method

1 - Prepare and Cook Onion

To begin with, we need to peel and chop one whole onion. Onions of all kinds were a staple of most cuisines from the neolothic period to modernity, as they’re hardy, filling vegetables that have a multitude of uses. In any case, chop this into fine chunks, so they cook evenly. When this is done, toss some olive oil into a pot, and heat it up over a medium high heat.

When the oil is shimmering, toss a couple of crushed cloves of garlic into the oil, along with your onions. On top of this, sprinkle some salt, some freshly ground black pepper, and some freshly ground coriander. Put all of this back onto a medium high heat for a few minutes while you deal with your carrots.

2 - Prepare and Cook Carrots

Go peel a few carrots - aim for about an equal amount of carrots to onions. When they’re peeled, slice them into discs - making sure they’re all the same size, so they cook evenly. Although orange carrots were fairly rare in antiquity, they’re the dominant strain today. But remember that throwing in some parsnips or heriloom carrots wouldn’t hurt either!

When your carrots are prepared, add them to your onions when the pot smells lovely and fragrant, and the onions have turned translucent. On top of your carrots and onions, pour about 500ml of a soup stock of your choice. I went with chicken stock here, to add a more meaty background taste, but any stock would work well enough here!

3 - Cook

Place your pot over a high heat, and let it come to a boil. When it hits a rolling boil, turn the heat down to low and let it simmer away for about 30 minutes, or until a knife, when stabbed into a piece of carrot, comes out easily.

Serve up in a bowl of your choice, garnish with a little sprig of parsley or cilantro, and dig in!

The finished soup is rather sweet, thanks to the carrots and onions, and has a lovely zesty taste thanks to the coriander. The broth thickened up nicely, and the carrot chunks softened into a toothsome mouthful.

Today, I’m going to be recreating a recipe for a German apple pie from the Registrum Coquine - the contents of which are suited for a middle-class palette of medieval European world

In any case, let’s now take a look at The World That Was! Follow along with my YouTube video, above! Consider supporting me on Patreon if you like my recipes!

Ingredients

6 apples

2 cups flour

water

butter (or oil)

ground cinnamon

ground nutmeg

cloves (either whole or ground)

honey (if the apples are too tart)

Method

1 - Peel and Chop Apples

To begin making an apple pie, we need apples. Though the original recipe doesn’t state any particular apples, tart apples tend to make the best filling. Peel your apples, and chop them into fairly evenly-sized chunks so they cook evenly. I found that about 6 apples suited a pie fit for about four people.

2 - Prepare the Filling

When your apples are chopped, go toss some butter (or oil) into a pot, and let it melt. When it’s foaming, toss in your freshly-grated nutmeg, cinnamon, and a few cloves, and stir them around so they’re all covered in hot butter. You can, of course, crush your cloves, but I enjoy the sensation of biting into a whole clove - it’s up to you!

When your spices have cooked a little, toss in your chopped apples! Stir everything around so they’re all covered in butter and let it all cook away over a medium heat for a few minutes - until they soften and turn golden. At this point, take them off the heat and let them rest while you make your dough.

3 - Make Pie Dough

Since the original recipe assumes people know how to do this, we’re going to be using a cup or two of plain flour mixed with a little water. Add it little by little until it comes together into a cohesive dough. Knead this together until it’s smooth, and roll out using a rolling pin. Do this twice - once for the base of the pie, and twice for the lid. Roll the dough out fairly thin, as the whole pie won’t be baked for too long.

Pour some olive oil (or butter) into a pie dish, and stretch your pie dough over it, tamping it down with your knuckles into the corners.

4 - Assemble Pie

Pour the cooked apples into your pie dish, spreading it out evenly. When this is done, place your other circle of dough over the top. Crimp the edges of the two discs of dough together - it doesn’t matter if it doesn’t look too pretty! It’ll bake wonderfully, and taste delicious either way!

When your pie is ready, toss the whole thing into the centre of an oven preheated to about 180°C/356°F for about 25 minutes!

When the pie is done, take it out of the oven to cool down to room temperature before dividing up and digging in! Drizzle some honey over the slice you’re eating to really amplify it’s texture!

The finished pie is delicious and sweet, the spices forming a lovely warming sensation with each bite. The texture of the cooked apples is practically melt-in-your-mouth, and contrasts with the pie crust! As a side note, the pie crust itself - once cool - is rather tough. However the crust on the base of the pie is soaked in the juice from the apples during the cooking process, and is a much more palatable part of the pie. If I were to make this again, I’d either omit the top lid of the pie, or remove it before serving.

Today, I’ll be making a simple cherry pudding recorded in the 14th century AD - from the region of the Holy Roman Empire! Cherries were (and still are) a very popular fruit to eat, given the extensive range at which they can be grown. The original recipe is recorded in The Forme of Cury - a 14th century English manuscript - but the origin of this recipe likely comes from a central European source, given the variety of recipes recorded here.

In any case, let’s now take a look at The World That Was! Follow along with my YouTube video, above. Consider supporting me on Patreon if you like my recipes!

Ingredients

500g fresh ripe red cherries

200ml red wine

100g white sugar

1 tbsp unsalted butter

100g soft white breadcrumbs

salt

Edible flowers (e.g. clover, lavender, etc)

Method

1 - Prepare the Cherries

To begin with, we need to wash, de-stem, and stone the cherries. Do this by cutting into them carefully with a knife, before using your thumb to dig out the stone. Do this to about half a kilogram of cherries.

When your cherries have been stoned for their sins, place them into a bowl, along with 100ml (or a cup) of red wine - I used a merlot here, but a sweet dessert wine would work nicely. On top of this, also add about 50 grams of white sugar. Mix and mash everything together until it forms a very thick, lumpy soup.

2 - Cook the Pudding

At this stage, place a tablespoon of butter into a large saucepan or pot. Place this over a high heat until it starts to melt. At this point, place your breadcrumbs and cherry-wine mix into the pot, along with another 50g of sugar. Mix everything together. If it’s looking a little dry, add in another cup of wine. Put this onto a medium-high heat and let it cook away for about 10-15 minutes. Keep the whole thing stirring as you cook it, so nothing sticks and burns onto the pot.

3 - Cool and Serve

The pudding should thicken up considerably, and act like a porridge when it’s done. Let everything cool a little, before spooning into a bowl of your choice. The original recipe claims that you should decorate it with edible flowers.

The finished pudding is super sweet and flavourful. The breadcrumbs soaked up the cherry juice and wine mixture and became fantastically smooth, with a sharp undertone (thanks to the wine). If you wanted to make an alcohol-free alternative, you could use some grape juice instead!

The pudding itself can also be used as a pie or tart filling, and firms up quite nicely if baked.

Today, I’ll be making a 13th century cheesecake, from Andalucía - the South of Spain! The original text is from a medieval cookbook, by Ibn Razin al-Tujibi, and the audience seems to be for elite members of society. Though today, it’s a simple and easy cake that anyone can make inside an hour!

In any case, let’s now take a look at The World That Was! Follow along with my YouTube video above!

Ingredients

1 cup flour

1 cup milk

1tbsps yeast (or 1/3 cup sourdough starter)

250g ricotta (or other soft white cheese)

honey

olive oil

cinnamon

Method

1 - Prepare Dough

To begin with, we need to make a simple dough. Pour a cup of flour into a bowl, along with a tablespoon of yeast. Dry yeast wouldn’t have been available in antiquity, but wild yeast from a sourdough starter would have been used, and a third of a cup can be used here.

Pour in a cup of room-temperature milk on top of this, along with a splash of olive oil. The original recipe calls for “fat” which can be any one of a huge number of things - like butter, lard, or oils - but olive oil would have also been used. Mix everything together until it takes on a very runny texture. Add a little water if your dough is too dry.

Cover this with a towel and leave it to raise over an hour or so in a warm area.

2 - Assemble Cake

After an hour, go oil up a baking dish. Pour in a ladleful of your dough, and spread it around the base.

On top of this, place a few dollops of ricotta cheese. White cheese is specified here - which again could mean any one of a number of cheeses, but ricotta, or a soft feta, would work well here. Ladle in another layer of dough, before repeating the ricotta process. You can also add some honey between these layers. Though this wasn’t specified, it adds a nice kick of sweetness to the final dish.

Repeat this layering process until you run out of cheese or dough, making sure the top of the cake is covered in a layer of dough.

Place your cake into an oven preheated to 250° C /485° F or as high as your oven will go, and let this bake for a half an hour, rotating it halfway through so it cooks evenly.

3 - Finish Cake

It should be done when the top of it is golden and firm. Pour some honey over the top of this while it’s cooling in the baking dish, and sprinkle some cinnamon over the honey. If you want, you could also use some freshly-ground black pepper which adds a nice warm background to the finished cake.

Leave to cool a bit at room temperature, and serve up!

The finished dish is super light and sweet, and although some of the ricotta didn’t melt completely during the baking process, they have a nice texture when biting into a piece. The cake itself is more like a very light, sweet bread, but is still a really nice and simple dish to make!

I find a big stumbling block that comes with teaching Romeo and Juliet is explaining Juliet’s age. Juliet is 13 - more precisely, she’s just on the cusp of turning 14. Though it’s not stated explicitly, Romeo is implied to be a teenager just a few years older than her - perhaps 15 or 16. Most people dismiss Juliet’s age by saying “that was normal back then” or “that’s just how it was.” This is fundamentally untrue, and I will explain why.

In Elizabethan England, girls could legally marry at 12 (boys at 14) but onlywith their father’s permission. However, it was normal for girls to marry after 18 (more commonly in early to mid twenties) and for boys to marry after 21 (more commonly in mid to late twenties). But at 14, a girl could legally marry without papa’s consent. Of course, in doing so she ran the risk of being disowned and left destitute, which is why it was so critical for a young man to obtain the father’s goodwill and permission first. Therein lies the reason why we are repeatedly told that Juliet is about to turn 14 in under 2 weeks. This was a critical turning point in her life.

In modern terms, this would be the equivalent of the law in many countries which states children can marry at 16 with their parents’ permission, or at 18 to whomever they choose - but we see it as pretty weird if someone marries at 16. They’re still a kid, we think to ourselves - why would their parents agree to this?

This is exactly the attitude we should take when we look at Romeo and Juliet’s clandestine marriage. Today it would be like two 16 year olds marrying in secret. This is NOT normal and would NOT have been received without a raised eyebrow from the audience. Modern audiences AND Elizabethan audiences both look at this and think THEY. ARE. KIDS.

Critically, it is also not normal for fathers to force daughters into marriage at this time. Lord Capulet initially makes a point of telling Juliet’s suitor Paris that “my will to her consent is but a part.” He tells Paris he wants to wait a few years before he lets Juliet marry, and informs him to woo her in the meantime. Obtaining the lady’s consent was of CRITICAL importance. It’s why so many of Shakespeare’s plays have such dazzling, well-matched lovers in them, and why men who try to force daughters to marry against their will seldom prosper. You had to let the lady make her own choice. Why?

Put simply, for her health. It was considered a scientific fact that a woman’s health was largely, if not solely, dependant on her womb. Once she reached menarche in her teenage years, it was important to see her fitted with a compatible sexual partner. (For aristocratic girls, who were healthier and enjoyed better diets, menarche generally occurred in the early teens rather than the later teens, as was more normal at the time). The womb was thought to need heat, pleasure, and conception if the woman was to flourish. Catholics might consider virginity a fit state for women, but the reformed English church thought it was borderline unhealthy - sex and marriage was sometimes even prescribed as a medical treatment. A neglected wife or widow could become sick from lack of (pleasurable) sex. Marrying an unfit sexual partner or an older man threatened to put a girl’s health at risk. An unsatisfied woman, made ill by her womb as a result - was a threat to the family unit and the stability of society as a whole. A satisfying sex life with a good husband meant a womb that had the heat it needed to thrive, and by extension a happy and healthy woman.

In Shakespeare’s plays, sexual compatibility between lovers manifests on the stage in wordplay. In Much Ado About Nothing, sparks fly as Benedick and Beatrice quarrel and banter, in comparison to the silence that pervades the relationship between Hero and Claudio, which sours very quickly. Compare to R+J - Lord Capulet tells Paris to woo Juliet, but the two do not communicate. But when Romeo and Juliet meet, their first speech takes the form of a sonnet. They might be young and foolish, but they arein love. Their speech betrays it.

Juliet, on the cusp of 14, would have been recognised as a girl who had reached a legal and biological turning point. Her sexual awakening was upon her, though she cares very little about marriage until she meets the man she loves. They talk, and he wins her wholehearted, unambiguous and enthusiastic consent - all excellent grounds for a relationship, if only she weren’t so young.

When Tybalt dies and Romeo is banished, Lord Capulet undergoes a monstrous change from doting father to tyrannical patriarch. Juilet’s consent has to take a back seat to the issue of securing the Capulet house. He needs to win back the prince’s favour and stabilise his family after the murder of his nephew. Juliet’s marriage to Paris is the best way to make that happen. Fathers didn’t ordinarily throw their daughters around the room to make them marry. Among the nobility, it was sometimes a sad fact that girls were simply expected to agree with their fathers’ choices. They might be coerced with threats of being disowned. But for the VAST majority of people in England - basically everyone non-aristocratic - the idea of forcing a daughter that young to marry would have been received with disgust. And even among the nobility it was only used as a last resort, when the welfare of the family was at stake. Note that aristocratic boys were often in the same position, and would also be coerced into advantageous marriages for the good of the family.

tl;dr:

Q. Was it normal for girls to marry at 13?

A. Hell no!

Q. Was it legalfor girls to marry at 13?

A. Not without dad’s consent - Friar Lawrence performs this dodgy ceremony only because he believes it might bring peace between the houses.

Q. Was it normal for fathers to force girls into marriage?

A. Not at this time in England. In noble families, daughters were expected to conform to their parents wishes, but a girl’s consent was encouraged, and the importance of compatibility was recognised.

Q. How should we explain Juliet’s age in modern terms?

A. A modern Juliet would be a 17 year old girl who’s close to turning 18. We all agree that girls should marry whomever they love, but not at 17, right? We’d say she’s still a kid and needs to wait a bit before rushing into this marriage. We acknowledge that she’d be experiencing her sexual awakening, but marrying at this age is odd - she’s still a child and legally neither her nor Romeo should be marrying without parental permission.

Q. Would Elizabethans have seen Juliet as a child?

A. YES. The force of this tragedy comes from the youth of the lovers. The Montagues and Capulets have created such a hateful, violent and dangerous world for their kids to grow up in that the pangs of teenage passion are enough to destroy the future of their houses. Something as simple as two kids falling in love is enough to lead to tragedy. Thatis the crux of the story and it should not be glossed over - Shakespeare made Juliet 13 going on 14 for a reason.

Romeo and Juliet is the Elizabethan equivalent of ‘won’t someone please think of the children’ it’s a romantic tragedy not a romance romantic in that it’s a love story but not a romance in the sense that it is supposed to be emulated and is likely a social commentary of something happening at the time whether it was ongoing religious feuds which did tear families apart uprisings across the country or just general malaise with how the world was going in the 1590s it’s also worth noting that R+J was based heavily on a poem writen some 30ish years prior by Arthur Brooke known as The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet which in turn was based on the work of Matteo Bandello who supposedly based most of his work on real life events making his association to Lucrezia Gonzaga an Italian noblewoman who was married off at the age of 14 likely to solidify some sort of alliance during turbulent times all the more poignant Shakespeare was and never has been the reserve of the intellectual and elite that we are taught his work without historical context robs us of the true value of his work social commentary and this social commentary would like to have a few words with your false ideas of ‘historical accuracy’ (via@thebibliosphere)

I saw this in my emails and couldn’t see why I’d been tagged in it (all the while nodding vehemently along) and then I saw my tags and ah. Yep. Still forever mad at how badly Shakespeare is taught in most schools.

Wait but then why does Juliet’s mother talk about being already married younger than Juliet currently is?

Likely because her match to Juliet’s father was an arranged match to solidify family names and houses in order to avoid conflicts or to establish wealth. (It also serves to denote the tragic undercurrent of the play ie love is secondary to wealth and power.)

It wasn’t so uncommon for children of royalty or nobility to be betrothed from birth, or even symbolically married, in order to make alliances. But that doesn’t mean they were engaging in the kind of adult relationship we envision when we think of marriage today.

Which isn’t to say some people didn’t buck the norm and do horrible things Margaret Beaufort is a prime example of this, which the Tudors would likely be aware of. Her first marriage contract actually happened when she was one year old. It was later dissolved and she was remarried at the age of 12, and her second husband, Edmund Tudor, did in fact get her pregnant before dying himself. She was 13 years old when she gave birth, and it caused major health issues for her and nearly killed her. When she survived it was considered miraculous. Which should tell you just how not normal this kind of thing was thought of even back then.

I agree with absolutely everything in this thread of discussion. Even so, my long-standing fascination with both Shakespeare and late medieval / early renaissance history makes it impossible for me to to reblog without throwing in my extra few cents:

I. Margaret Beaufort

In my mind, there are few cases that better demonstrate the tensions between medieval norms and medieval realities than that of Margaret Beaufort. Like many other women of her time, she had only one child surviving to adulthood: Henry Tudor (later Henry VII and the founder of the Tudor dynasty). In that, Margaret wasn’t so remarkable: infant mortality made this a common enough outcome, though undoubtedly a tragic one.

Where Margaret’s case was exceptional is that Henry was also her only known pregnancy, without so much as a stillbirth, infant death, or even another pregnancy ever being mentioned in connection to her. In her own time, it was commonly assumed that her experience of childbirth at a very young age was what accounted for her barrenness, and even to us today, it doesn’t seem implausible to assume some kind of physical trauma that prevented later pregnancies from taking place, given all the medical knowledge we’ve accumulated about the risks of childbirth at either extreme of age.

But there was more to this. The vast Beaufort estate that came with Margaret’s young hand were so valuable that, to 15th/16th century English minds, it perfectly explained Edmund Tudor’s motives for having been so reckless with the health of his wife: having an heir of his own would ensure that her lands would stay with him, in the name of any children they might have together, whereas the lands would pass to someone else if she should die before having a child. Of course, most men in that situation would have waited anyway, as a child whose mother died in childbirth was much less likely to survive anyway, so contemporaries portrayed Edmund Tudor’s actions as short-sighted and foolhardy at best, amoral and cruel and worst. But Fate must have a sense of irony, because Edmund died before his son was even born, while Margaret lived, and as aristocratic women tended to do in those circumstances, she was remarried to Henry Stafford, 1st Duke of Buckingham.

Since Margaret was Stafford’s first (and only) wife, he would have depended on her to give himany heirs at all, to whom he could pass on the lands he alreadyhad, let alone any of Margaret’s own (and it would be logical to assume that the Beaufort inheritance would have been no less tempting to Stafford than it was to Tudor). He must have at least hoped for children from her, and at the time, there wasn’t any reason to expect she was totally barren either: there was the traumatic birth to consider, but she was more physically mature when she remarried, and there was room to hope that widowhood had given her time to recover. And yet, despite all this, it seems few people (if any) were surprised that Margaret did not bear any more children. It didn’t seem to doom her relationship with her second husband either: on the contrary, Margaret enjoyed a happy relationship with Stafford for well over a decade until his death, so if there was any bitterness on his part over his lack of heirs, he must have managed it well. Even in the contemporary sources (who don’t tend to be charitable towards female figures), any blame for her barrenness is laid squarely at the feet of the various men who were her guardians in her early life, who clearly abused their authority over her for their own benefit, rather than to safeguard Margaret’s well-being as guardians are supposed to do (one of them being Edmund Tudor himself… he wasn’t supposed to even be in the running for her wardship, but Henry VI actually outright broke a promise he had made to Margaret’s father to let Margaret’s mother be her guardian in the event of his death).

This indicates to me even more strongly that late-medieval / Tudor people would have not only been sympathetic towards what Margaret and women like her had suffered, but also understood that neglectful attitudes towards the health and happiness of dependents have consequences. Shakespeare’s own words make this clear, at the beginning of the play:

Paris: Younger than she are happy mothers made.

Capulet: And too soon marr’d are those so early made.Tudor audiences would have understood these lines as the words of a benevolent father protecting his daughter from the advances of an overeager young suitor, invoking what seems to have been a Tudor-era trope that early marriages do not make for happy endings… not for the woman, not for her family or husband, and certainly not for the children she might otherwise have borne. Because Capulet came off as the “good father” in the beginning of the play, it makes it all the more shocking when his attitude changes and he becomes the all-too-familiar figure of the cold, uncaring patriarch who regards his children only as pawns*. I imagine the juxtaposition would have invited Tudor audiences to feel Juliet’s sense of betrayal as if it were happening to them.

* Jane Grey, the famed “nine days’ queen” was also rumored to be such a victim of her parents’ ambition: they also saw fit to force her into a marriage that she seriously objected to, and historical records point a fairly consistent picture of their callous disregard towards her wishes and genuine happiness.

II. Consent in Medieval Marriages

Twelve and fourteen are actually also important numbers in their own right, and Shakespeare’s choice to place Juliet between those two ages has an important symbolic meaning. Late medieval Catholic doctrine defined marriage as a sacrament, like the Eucharist (Communion), or Holy Orders. Many of the sacraments require those who receive them to understand what they’re getting into for the sacrament to have the desired effect. To guarantee understanding (at least from a theological perspective), you would have to be above “the age of reason”, the age at which you were considered to be able to think for yourself. Conservative definitions of the “age of reason” sometimes defined it as the age of fifteen or fourteen (or older), but was later fixed at twelve. Since marriage was one of these sacraments, a marriage where both spouses had notfully and knowingly given their consent was no marriage at all.* Therefore, twelve was considered the absolute lower age limit at which a person could marry without compromising the very spiritual foundation of the marriage itself, while fourteen was considered a safer age at which to assume the person had full control of their reasoning capacities.

The other side of the “consent” coin when it came to marriage was that consent wasn’t just a necessary condition to finalize a marriage, it was also sufficient condition. If a man and a woman had given their knowing consent to marry one another, and if they had intentionally verbalized this promise to one another and consummated their marriage, then no earthly power could invalidate this pact for any reason (outside of a few very specific ones, like incest) without risking damnation. Witnesses were convenient as a way to prove that the marriage had taken place, if a family member or some segment of society disapproved of the match, but they weren’t needed in order to make the marriage spirituallyvalid. Basically, the Catholic Church at this stage somehow ended up putting the idea of consent at the very heart of the idea of what made a marriage valid or not, and this had consequencesnot only because of the threat of hellfire, but also because Church law was secular law when it came to domestic matters like marriage and divorce. And then it came to pass that the English Reformation left this specific area of the doctrine mostly untouched, so the Tudors would have had similar ideas surrounding the question of consent and marriage as did their late medieval forbears.

This theological point is not only the whole raison d’etre for the most central plot device in the play, but also adds an extra note of pathos to Juliet’s situation and an extra layer of moral judgment towards Lord Capulet’s behavior. If she did not insist on keeping her marriage vow, or if she married Paris knowing full well that she had already been married, both of those would be mortal sins for which she would risk damnation. And by extension, because he used duress against Juliet to try to make her comply with his sinful wish, Lord Capulet has also damned himself (albeit unknowingly, but even so, the narrative clearly presents forcing his daughter’s marriage as something he should know better than to do, anyway).

Until this point, Juliet’s marriage is characterized as an impulsive decision such as only foolish youth could make, but ironically, in that confrontation with Lord Capulet, this slip of a young girl is now portrayed as conducting herself with far more spiritual maturity and grace than any of the adults around her. Her parents are failing in their duty towards her by putting their dynastic concerns ahead of her health and happiness (when it’s been made clear they already know this is a Bad Idea), and her Nurse, who actually knows about the secret marriage and all the reasons why it cannotbe taken back, is actively pleading with her to just forget it and pretend Romeo never was. Juliet’s choice here is monumental, because it involves not only disregarding her parents, but also an active decision to completely break with the woman who has been with her for literally everything in her life up to that point, a break so thorough that even Nurse herself doesn’t know that it’s happened. This dramatic turning point is a bittersweet portrait of the girl losing her innocence and growing up into an adult, from one angle, and from another angle it’s a paean to the pure-hearted idealism (different from the limpid innocence of childhood in that it’s willful and risk-taking, and fiery in quality) that can only be found in the young. Either way, it does Juliet’s character AND Shakespeare’s dramatic talents a massive disservice to portray her situation as something so simplistic or reactionary as lovelorn pining after an absent boyfriend, or rebelling against her parents, or “staying true to her own heart”.

This wasn’t just a plot device for the stage: many real-life lovers leaned on this feature of the Church’s teachings, when faced with the opposition of their families and communities, and in many cases, the Church was indeed forced to side with the couple, however reluctantly. Margery Paston, the daughter of a genteel landowning family in the 15th century, and Richard Calle, the Paston family’s longtime housekeeper, were one such case of a real-life Romeo and Juliet: they mutually fell in love, and married in secret when they came up against heavy opposition from Margery’s family. The Pastons responded by separating them, firing Calle from his job and having him sent to London, while Margery remained in Norfolk under house arrest. There, she seems to have been subjected to ongoing and intense pressure to walk back her marriage… if the couple had been married formally in church, this would not have been possible, but secret marriages were vulnerable to challenges like this because they were secret. A witness would have helped her and Calle’s case and made it more airtight, but even if the couple had had any, apparently the Pastons had succeeded in intimidating them into silence.

But even though the Pastons seemed to be winning, it’s hard to believe that bystanders wouldn’t have objected to at least some of what the Pastons were doing to try and get their way. Otherwise, Calle could not have written Margery in 1469, during their separation, saying “I suppose if you tell them sadly the truth, they will not damn their souls for us”. Their situation was objectively quite bleak. For the months they were apart, it was made very clear to both Margery and Calle that, if the couple continued to insist on their marriage, the Pastons would disown Margery and throw her out of the house, therefore leaving her with few options for survival, let alone to find her way to Calle over a distance of a hundred miles. He mournfully acknowledges that their gamble might fail, and their worst fears might come true, but there is also defiance in his resignation, as he concludes, “if they will in no wise agree [to respect our marriage], between God, the Devil and them be it.”

Margery, for her part, was no less determined. When Margery was finally brought before the local bishop, he turned out to be sympathetic towards the Paston family, and gave Margery a long speech about the importance of pleasing her family and community (so much for the theological importance of consent, but then, clerical hypocrisy was nothing new to medieval people). But Margery remained steadfast (in fact, I am inclined to think from her next words that the bishop’s words only goaded her to greater resolve) and when she spoke, she not only continued to insist that she had said what she had said, but according to her mother she “boldly” added, “if those words made it not sure […] she would make it surer before she went thence, for she said she thought in her conscience she was bound [in marriage to Calle], whatsoever the words were.” Her wording left absolutely no room for doubt in the mind of even the most flexible theologian. And when Calle was cross-examined and his testimony found to match that of Margery’s, the bishop of Norfolk had no choice but to rule in the couple’s favor.

Margery’s mother did indeed make good on her word: she didboth disown Margery and throw her out of the house. She seemed to have done it more to save face, however, than to actually punish her daughter, since she does seem to have made arrangements behind the scenes for Margery to stay with sympathetic neighbors. In the end, Calle was right, the Pastons were not willing to risk their own souls. Margery and Richard Calle got their happy ending, and had at least three children (and we know about them because we know Margery’s mother left them money in her own will).

* This also meant that Edmund Tudor actually would have been Margaret Beaufort’s first husband, not her second. It was true that she had already been “in a marriage” before being married later to Tudor, but strictly speaking, it was only a precontract (what we today would think of as an engagement) with signficance limited to the secular realm; there are a lot of reasons this would not have really been considered a marriage at the time, but the most theologically pertinent one is that the bride’s consent could not have been involved, because she was too young to be able to give it. Consequently, this paper marriage was easily dissolved as soon as her guardians thought it more politically expedient to marry her to Edmund Tudor. And for all intents and purposes, Margaret Beaufort herself considered Tudor to be her first husband, not John de la Pole.

tl;dr: the study of Shakespeare cannot be separated from historical and societal understanding of the times he lived in, and frankly, it’s a terrible shame that English classes don’t emphasize this more, because then you’re throwing out about 80% of the meaning his works actually hold.Sorry to keep reblogging this long post but holy shit this is an excellent addition. Thank you for taking the time to write all that up.

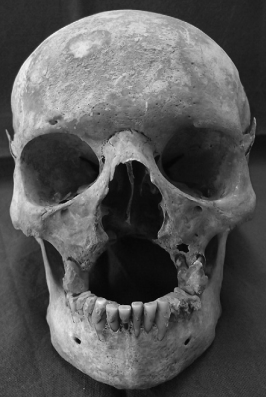

Some Good My Gentle Master for God’s Sake, acrylic on canvas, 2019

Source: Three skulls showing the effects of leprosy (middle images). Title references the text above a medieval illumination of a leper holding a bell (bottom image).

Lepers weren’t stigmatized in medieval Europe, and in fact were held in high regard. Their suffering on earth guaranteed them a place in heaven without having to spend time in purgatory first. The reason they were pictured with bells was because the disease affected the vocal chords which made speaking difficult. The bell was used for communication, not as a warning.

Post link

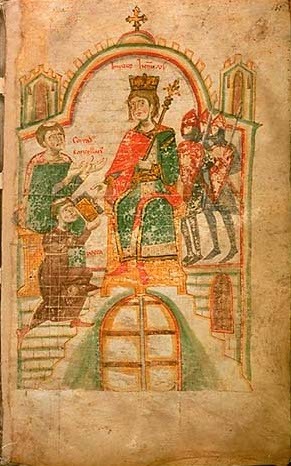

A Leaf From the Ebulo Codex - An Example of Poor-Quality Parchment

The Ebulo Codex was painted on sheepskin parchment, as can be deduced by its yellow tint in the first example photo. This parchment had evidently not undergone a complete scraping process, however. Residual layers of skin on the hide (inner) side of the parchment left it too greasy to retain the paint applied to it, leading to considerable chipping and fading.

Location:Burgerbibliotek, Bern (Switzerland)

Usage Rights: Public Domain

Reference:

Quandt, Abigail. “Recent Developments in the Conservation of Parchment Manuscripts.” Book and Paper Group Annual, vol.15. https://cool.conservation-us.org/coolaic/sg/bpg/annual/v15/bp15-14.html

Post link

The evolution of the pilcrow, or “paragraph symbol.”

“[…] [B]y the 12th century, scribes abandoned the K in favor of the C, for capitulum (“little head”) to divide texts into capitula (also known as “chapters”). Like the treble clef, the pilcrow evolved due to the inconsistencies inherent in hand-drawing, and as it became more widely used, the C gained a vertical line (in keeping with the latest rubrication trends) and other, more elaborate embellishments, eventually becoming the character seen at the top of this post.”

Post link

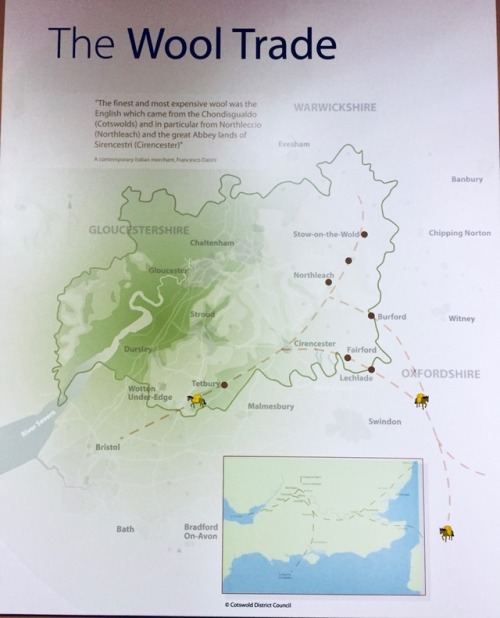

Corinium Museum, Cirencester; Medieval Period

Wool Mark of John Fortey (d. 1459

From his brass in Northleach Parish Church

my notes;

Monumental brasses are a kind of memorial which grew in popularity during the 13th century, allowing detailed representations of the dead to be made for much less money than full stone or wooden effigies, which could be laid into the floors and therefore take up much less space. They were a favoured style of funerary art until the 16th century across Europe, the vast majority of these brasses survive in England (totalling around 4000). A great many of these are found in the eastern counties, although there is a large concentration of them around Cirencester, Northleach, and Lechlade.

Post link

Corinium Museum, Cirencester; Medieval Period

The Wool Trade (my notes)

The production of wool was enormously important to England for many centuries, and for the Cotswolds in particular. The climate and terrain of the area made it idea for rearing sheep, and the native sheep breeds were prized for their rich golden wool. Towns and villages grew up along the trade routes, merchants amassed large amounts of money which was spent on lavish houses, and grand “wool churches” were built on the proceeds. A great number of the herds were owned by the numbers of Abbeys established in the area, furthering the success of already growing power of the church. By the 1100s, 50% of the economy of the Cotswolds was based in the rearing of sheep for their wool, and by the 14th century this was true for the income for the entire country.

Cirencester sits at one of the major crossroads in a prime location for both moving wool and other goods to and from major ports, but also for transportation into the Stroud valleys, which still contain a huge concentration of textile mills.

The Cotswold Lion

Sheep have grazed on the Cotswold hills for more than 2000 years. The most famous breed was the Cotswold Lion, the producer of a long curly fleece which became famous throughout Europe. An ideal wool for dyeing, it became a favourite for spinning and weaving. Merchants grew rich and built many churches with their profits.

This fine example (in image 2) comes from a local flock by the name of Noent, his own name is Emperor. Kindly donated by Mr E Freeman.

Post link

Corinium Museum, Cirencester; Medieval Period

Unidentified Grave Cover

Early 13th century decorated grave cover from Cirencester Abbey

Post link

Corinium Museum, Cirencester; Medieval Period

Replica brass of Reginald Spycer (d. 1442)

This depicts Spycer and his four wives, Margaret, Juliana, Margaret and his widow Joan, a vivid testimony to the mortality rate amongst women.

From Trinity Chapel, Cirencester Parish Church

my notes;

Monumental brasses are a kind of memorial which grew in popularity during the 13th century, allowing detailed representations of the dead to be made for much less money than full stone or wooden effigies, which could be laid into the floors and therefore take up much less space. They were a favoured style of funerary art until the 16th century across Europe, the vast majority of these brasses survive in England (totalling around 4000). A great many of these are found in the eastern counties, although there is a large concentration of them around Cirencester, Northleach, and Lechlade.

Post link

![The evolution of the pilcrow, or “paragraph symbol.”“[…] [B]y the 12th century, scribes aband The evolution of the pilcrow, or “paragraph symbol.”“[…] [B]y the 12th century, scribes aband](https://64.media.tumblr.com/8c283229680e039e2523c361fb7bee8c/tumblr_mqpexoGbki1sxhurao1_500.jpg)

![The evolution of the pilcrow, or “paragraph symbol.”“[…] [B]y the 12th century, scribes aband The evolution of the pilcrow, or “paragraph symbol.”“[…] [B]y the 12th century, scribes aband](https://64.media.tumblr.com/d7892ef2de8da431c0629027f1749fe4/tumblr_mqpexoGbki1sxhurao2_500.jpg)