#incunable

If you’re in the habit of reading descriptions of old books—and why wouldn’t you be?—you’ve likely come across something described as bound in period style or in a sympathetic binding. This typically means the book was rebound relatively recently, but rebound in a style consistent with the time period of the book’s original publication.

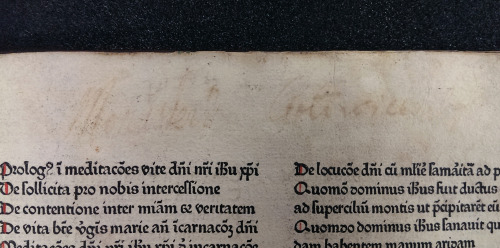

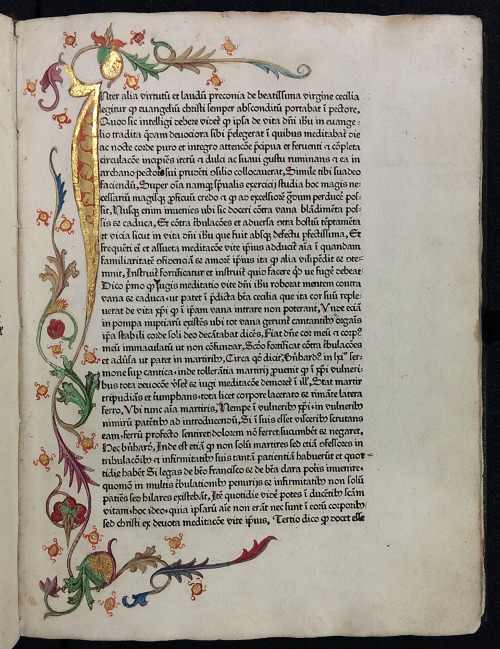

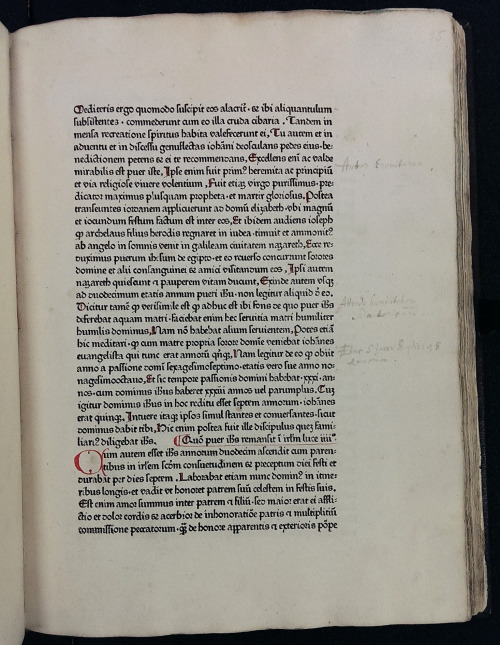

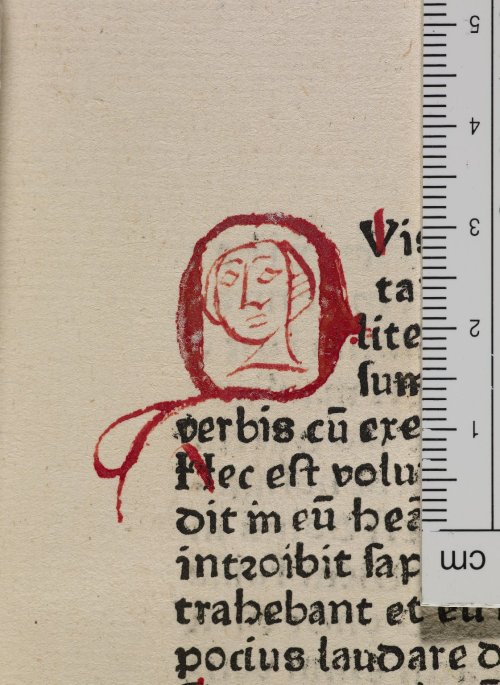

For example, our first edition of the Meditationes Vitae Christi (Meditations on the Life of Christ) was rebound in such a way. You can read more about this work—a recent acquistion—here.

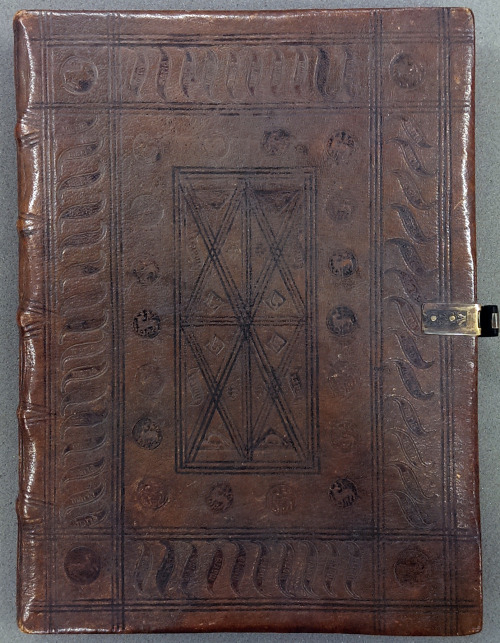

And shortly after the Meditations arrived, we received the first printed Greek edition of Aristotle (it was a very good summer), which underscored just how well done this period-style binding was. Although the books were likely bound about 400 years apart—the Aristotle around 1500 and the Meditations around 1900—the styles are strikingly similar. The combination of borders built up from different tools, surrounding a central diaper pattern, was a familiar style when both were published. The Aristotle binding is almost certainly German, so it’s no surprise that the binding of the Meditations, which was printed in Augsburg in 1468, emulates a 15th-century German style.

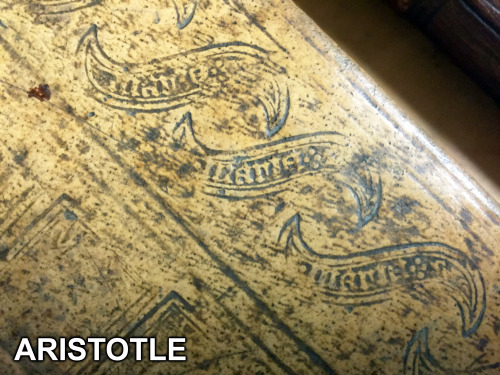

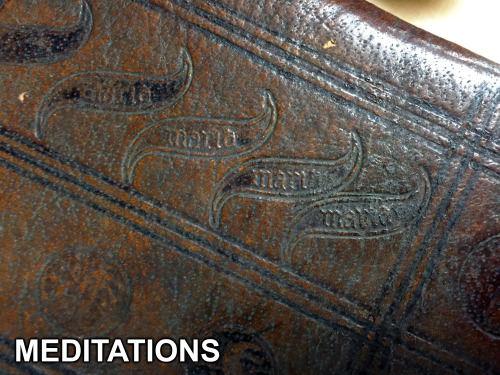

Of all the similarities, what most caught our eyes was a particular tool used to decorate the boards. While obviously similar, small differences distinguish them. The Aristotle version, for example, has four tiny dots following Maria, while the Meditations version has no dots; a double border surrounds the Aristotle tool—thick on the outside, thin on the inside—while the Meditations tool has a single border; the Aristotle tool measures over 3 cm from end to end, while the Meditations tool measures just under 3 cm. The sheer volume of such tiny differences among tools is staggering. The Einbanddatenbank, a database of 15th- and 16th-century finishing tools used on German bindings, records more than 600 versions of the Mariatool.

How do we know the Meditations binding isn’t original? There are a number of clues, the general as-new appearance being a big one, but subtler evidence is there. The spine edges of wooden boards were commonly beveled in the late 15th century, but they aren’t here. Spines were seldom decorated at this time, yet the binder of the Meditations couldn’t help but to add some restrained decoration. Could these features be found on bindings from the late 15th century? Sure. But the accumulated weight of the evidence favors something done later in period style.

Make no mistake, the Meditations binder was good. Even the endpapers are period-appropriate leaves removed from an old book. This binding was absolutely the product of a skilled craftsperson with a thorough understanding of period styles—and perhaps the product of a binder with the skill and patience to make their own finishing tools.

~Pat

Post link

One way to measure the popularity of a given text is to count the number of times it’s been published. For example, the immense popularity of The Imitation of Christ, which went through 78 editions in the 15th century, has been said to trail only the popularity of the bible itself as a devotional text. Compare these to 15 editions of Dante’s Divine Comedy in the 15th century and one can begin to appreciate just how popular Christian devotional literature once was. As it happens, MSU has one of just eight known copies of a rare 1495 editionofThe Imitation of Christ.

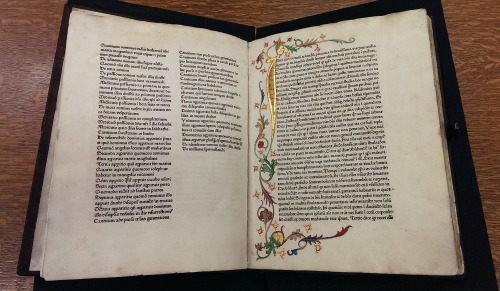

Not far behind the popularity of The Imitation of Christ, with at least 65 editions appearing in the 15th century, is the Meditations on the Life of Christ. MSU is very fortunate to have recently acquired the first printed edition of the Meditations—the very first of those many editions to appear in the 15th century (pictured above). Published in 1468, this edition has the distinction of being the first dated book printed in the city of Augsburg—and this at a time when fewer than a dozen cities in all of Europe had the technology to print books. This first appearance in print is a fine complement to our medieval manuscript of the text, and it also claims the honor of being one of the three oldest printed books to reside in Michigan.

On the front paste-down of our Meditations, afloat in a sea of booksellers’ annotations, is the bookplate of Hieronymus Baumgartner (1498-1565), a powerful advocate of the Protestant Reformation. Baumgartner enrolled at the University of Wittenberg in 1518, the very town in which just a year earlier Martin Luther allegedly nailed his Ninety-five Theses to a church door. In Wittenberg, Baumgartner befriended prominent reformers Philipp Melanchthon, Georg Major, and Joachim Camerarius, and he later helped found the Melanchthon Gymnasium in his hometown of Nuremberg in 1526. Baumgartner was an accomplished statesman, to be sure, but we’re particularly pleased because his bookplate, as far as we can tell, is the oldest bookplate in MSU’s collection.

~Pat

This Provenance Project guest post was written by Patrick Olson, Rare Books Librarian at Michigan State University Special Collections.

Post link

Auct. 4Q 4.18 Sermones de tempore et de sanctis by Peregrinus Strasbourg: Printer of Henricus Ariminensis, c.1474-7 (bodley30.bodley.ox.ac.uk)

Post link