#incunabula

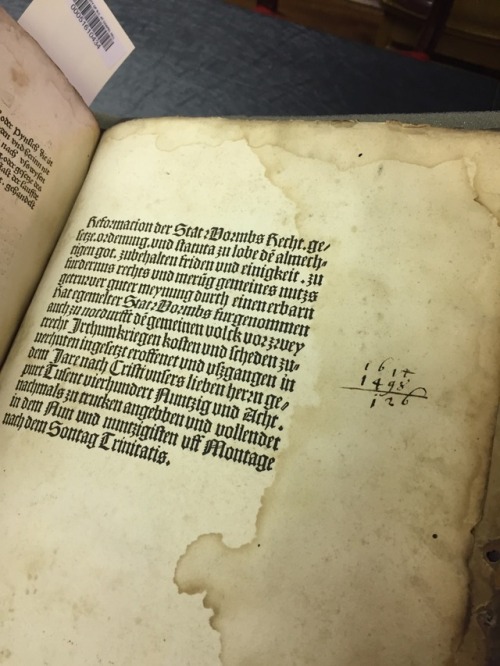

Today’s highlight from our Rare Books Collection is some charming marginalia from our copy Der Statt Wormbs Reformation . From what we can tell, the annotator was trying to figure out the time that had passed between the first printing of this text and the year 1614. However, this owner slightly bungled both the original publication date (1499, not 1498) and the math (the difference should have been 116)!

Despite those few mishaps, though, this piece of marginalia is still a favorite of mine. Although the annotation is small, this subtraction makes a nice addition to the work of anyone studying reader-text interactions!

Post link

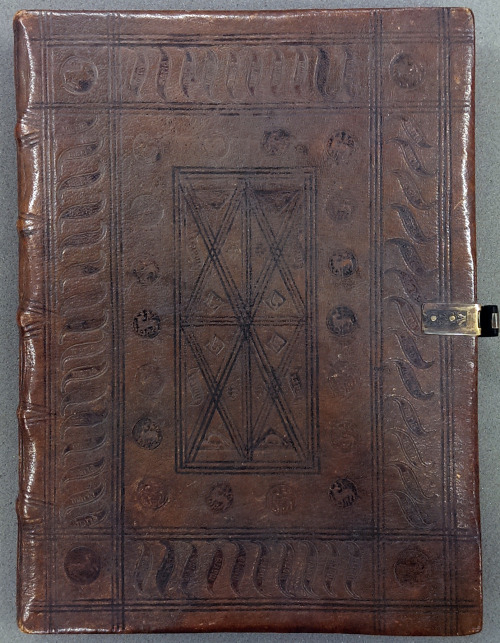

If you’re in the habit of reading descriptions of old books—and why wouldn’t you be?—you’ve likely come across something described as bound in period style or in a sympathetic binding. This typically means the book was rebound relatively recently, but rebound in a style consistent with the time period of the book’s original publication.

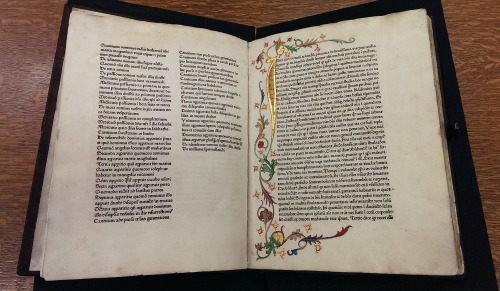

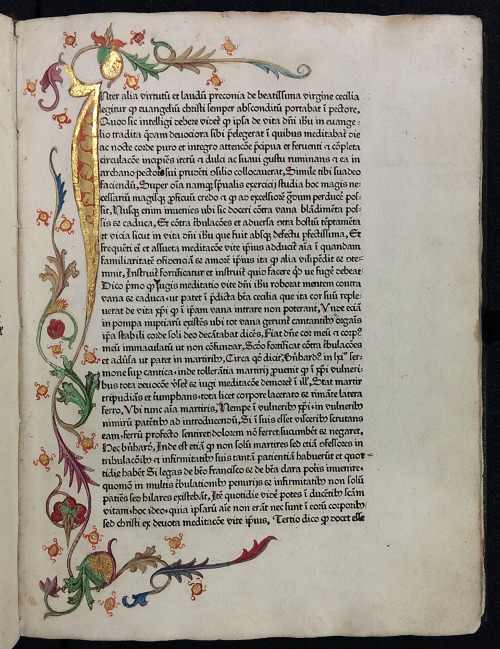

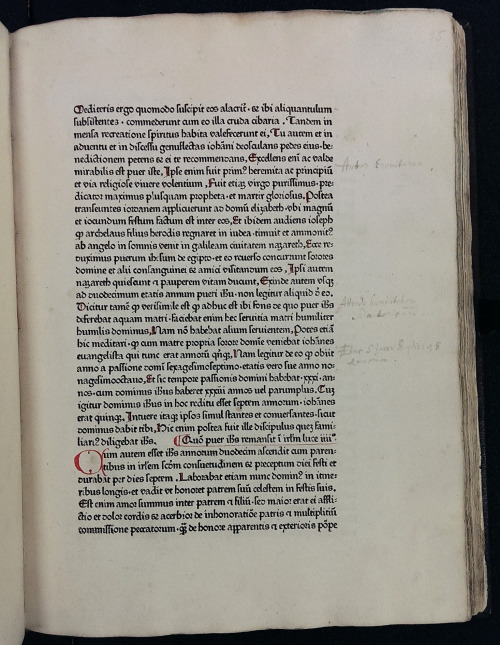

For example, our first edition of the Meditationes Vitae Christi (Meditations on the Life of Christ) was rebound in such a way. You can read more about this work—a recent acquistion—here.

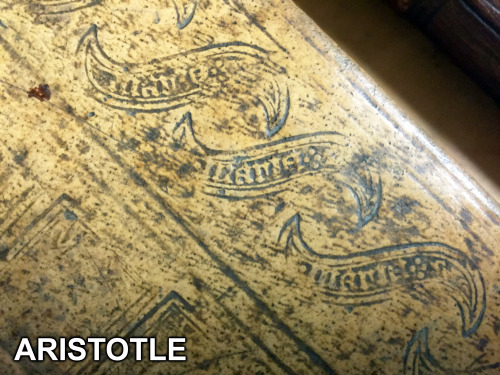

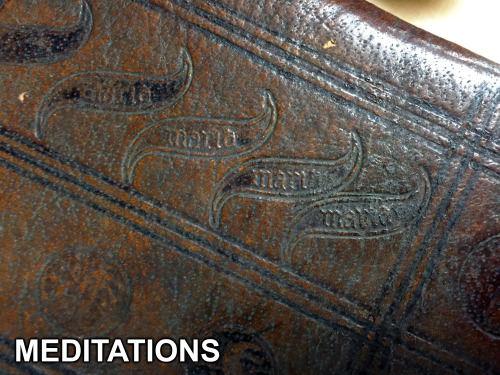

And shortly after the Meditations arrived, we received the first printed Greek edition of Aristotle (it was a very good summer), which underscored just how well done this period-style binding was. Although the books were likely bound about 400 years apart—the Aristotle around 1500 and the Meditations around 1900—the styles are strikingly similar. The combination of borders built up from different tools, surrounding a central diaper pattern, was a familiar style when both were published. The Aristotle binding is almost certainly German, so it’s no surprise that the binding of the Meditations, which was printed in Augsburg in 1468, emulates a 15th-century German style.

Of all the similarities, what most caught our eyes was a particular tool used to decorate the boards. While obviously similar, small differences distinguish them. The Aristotle version, for example, has four tiny dots following Maria, while the Meditations version has no dots; a double border surrounds the Aristotle tool—thick on the outside, thin on the inside—while the Meditations tool has a single border; the Aristotle tool measures over 3 cm from end to end, while the Meditations tool measures just under 3 cm. The sheer volume of such tiny differences among tools is staggering. The Einbanddatenbank, a database of 15th- and 16th-century finishing tools used on German bindings, records more than 600 versions of the Mariatool.

How do we know the Meditations binding isn’t original? There are a number of clues, the general as-new appearance being a big one, but subtler evidence is there. The spine edges of wooden boards were commonly beveled in the late 15th century, but they aren’t here. Spines were seldom decorated at this time, yet the binder of the Meditations couldn’t help but to add some restrained decoration. Could these features be found on bindings from the late 15th century? Sure. But the accumulated weight of the evidence favors something done later in period style.

Make no mistake, the Meditations binder was good. Even the endpapers are period-appropriate leaves removed from an old book. This binding was absolutely the product of a skilled craftsperson with a thorough understanding of period styles—and perhaps the product of a binder with the skill and patience to make their own finishing tools.

~Pat

Post link

One way to measure the popularity of a given text is to count the number of times it’s been published. For example, the immense popularity of The Imitation of Christ, which went through 78 editions in the 15th century, has been said to trail only the popularity of the bible itself as a devotional text. Compare these to 15 editions of Dante’s Divine Comedy in the 15th century and one can begin to appreciate just how popular Christian devotional literature once was. As it happens, MSU has one of just eight known copies of a rare 1495 editionofThe Imitation of Christ.

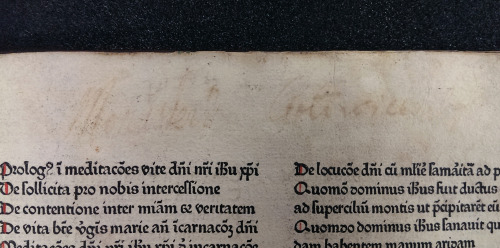

Not far behind the popularity of The Imitation of Christ, with at least 65 editions appearing in the 15th century, is the Meditations on the Life of Christ. MSU is very fortunate to have recently acquired the first printed edition of the Meditations—the very first of those many editions to appear in the 15th century (pictured above). Published in 1468, this edition has the distinction of being the first dated book printed in the city of Augsburg—and this at a time when fewer than a dozen cities in all of Europe had the technology to print books. This first appearance in print is a fine complement to our medieval manuscript of the text, and it also claims the honor of being one of the three oldest printed books to reside in Michigan.

On the front paste-down of our Meditations, afloat in a sea of booksellers’ annotations, is the bookplate of Hieronymus Baumgartner (1498-1565), a powerful advocate of the Protestant Reformation. Baumgartner enrolled at the University of Wittenberg in 1518, the very town in which just a year earlier Martin Luther allegedly nailed his Ninety-five Theses to a church door. In Wittenberg, Baumgartner befriended prominent reformers Philipp Melanchthon, Georg Major, and Joachim Camerarius, and he later helped found the Melanchthon Gymnasium in his hometown of Nuremberg in 1526. Baumgartner was an accomplished statesman, to be sure, but we’re particularly pleased because his bookplate, as far as we can tell, is the oldest bookplate in MSU’s collection.

~Pat

This Provenance Project guest post was written by Patrick Olson, Rare Books Librarian at Michigan State University Special Collections.

Post link

written by Katie Funderberg

Although less momentous than William Caxton’s first edition and certainly less ornate than the later Kelmscott Chaucer, Wynkyn de Worde’s The boke of Chaucer named Caunterbury tales (Incunabula Q. 821 C39c 1498) provides valuable insight into early English print history. As one of the most prolific English printers at the turn of the 16th century, de Worde’s initial years in the book trade—including the printing of the 1498 The boke of Chaucer—merit careful consideration. The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s copy, housed in the incunabula collection at the Rare Books and Manuscript Library, is a particularly useful case study example of de Worde’s early career at Westminster, as it is one of the most complete of the six copies known to exist. While several copies consist of only a few leaves, the volume owned by the RBML has 113 of the original 153 folia. Additionally, the leaves missing from the RBML copy were replaced with facsimiles produced by the British Museum in 1886, offering evidence of late 19th century attempts at book conservation as well as further information about the volume’s provenance.

According to the cataloger’s note in the page gutter of RBML’s copy, the university purchased The boke of Chaucer from Stonehill in 1956, over 450 years after its printing. The additional material pasted onto the front flyleaves make it clear that the book was previously owned by the British Museum before coming to reside in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library. On the recto of the second front flyleaf, there is a bill from Daniel C. Baxter to Major C. H. Fisher dated January 27, 1886 listing the charges for the facsimile leaves and woodcuts. The bill comes to a total of nine pounds, twelve shillings, and nine pence, with individual charges such as, “40,713 words, or 565 ½ folios, in ordinary writing at 2d per folio” costing £4.14.3 and “17 tracings of woodcuts in facsimile (charged for by time)” being £2.0.0. More information is provided on the recto of the fifth flyleaf in a short note dated January 28, 1886 and signed “Edward Ernest Stride, British Museum,” which reads: “The leaves supplied in MS. and the tracings of the woodcuts & of the printer’s mark have been executed by Mr D. C. Baxter, of the Dept. of Printed Books, British Museum.” Additionally, on the recto of the fourth flyleaf, someone—presumably Baxter—has written, “The following memorandum is pasted into the copy of this work in the British Museum, and is believed to have been inserted by Sir Thomas Grenville; who bequeathed this work with his library, to the Museum,” indicating that the missing text and illustrations have been copied from The boke of Chaucer in the Grenville collection, currently housed at the British Library.

Although Grenville’s donation of The boke of Chaucer made the additions to the copy possible, the resulting facsimile text, done in a 19th century cursive hand, is jarringly different than the original text used by de Worde, especially when they appear together on the same leaf. Contrary to the typical goals of 21st century conservationists, Baxter was more concerned with preserving the literary narrative than the unique condition of the incunabula. The woodcuts, however, are well executed and, despite being obviously pasted in, closely resemble the printed illustrations. RBML’s copy has a contemporary binding of brown, blind-tooled calf over wooden boards with two brass clasps on the back board and evidence of two additional clasps on the front board. Based on the eight-petaled flower watermark found throughout the copy, The boke of Chaucer was printed on paper made by John Tate the Younger, owner of the first paper mill in England. Instead of importing paper from France like most English printers, de Worde used Tate’s paper for several books, including his 1495 English translation of De proprietatibus rerum, in which the verse epilogue “makes the first known mention of paper making in England” by referencing the work of John Tate the Younger.

Fortunately, the stable physical condition of the RBML copy of de Worde’s The boke of Chaucer allows the book to be regularly used in class sessions at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library. In addition to courses focusing on English print history, the copy is also utilized for more general typography and graphic design instruction. The RBML copy of The boke of Chaucer is evidence, not only of Wynkyn de Worde’s legacy as one of the forefathers of English printing, but also how later bibliophiles and book restorers engage with his early work.

Johannes de Sacrobosco – Scientist of the Day

Johannes de Sacrobosco, an English cleric, astronomer, and teacher, lived in the first half of the 13th century; he was born before 1200 C.E., and died between 1236 and 1256 C.E.

read more…

Post link

Banned Books Week 2018

On Thursday evening (27 September), Fiona Oliver (Curator NZ and Pacific Publications), Anthony Tedeschi (Curator Rare Books and Fine Printing) and Mary Skarott (Research Librarian Children’s Literature), will present a good-humoured survey of some of the controversial and banned publications from the collections of the Alexander Turnbull Library and the National Children’s Collection.

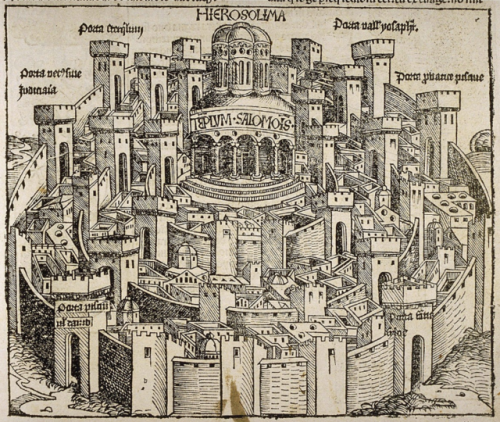

Among the items chosen from the Rare Books and Fine Printing Collection is the Liber chronicarum (1493), known more commonly as the Nuremberg Chronicle. The book came under censorship from the Holy See for its inclusion of an engraving depicting Pope Joan and her child (leaf clxix verso).

According to the legend, Joan disguised herself as a man and was elected Pope in 855. She was discovered when her water broke during a papal procession and she died shortly after giving birth to a son.

Pope Joan was believed to be a historical figure until the early-17th century when Pope Clement VIII refuted the story. The pope’s refutation - along with other criticism - resulted in the account and image of Pope Joan being excised, pasted over or otherwise defaced in a number of copies of the Liber chronicarum.

Other books being shown during the Banned Books event include: the first editions of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass (1855) and Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species (1859), the 1928 first edition of D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover published in Italy and Thomas Bowdler’s The family Shakespeare (1874 edition).

Post link

Newly Catalogued Incunabula

Earlier this year the Alexander Turnbull Library received a generous bequest from the estate of Mt John Barton, a New Zealand book collector resident in the town of New Plymouth.

Mr Barton (1931-2016) was born on Mersea Island off the coast of Essex, England. Around 1954, his family immigrated to New Zealand and settled in Taranaki. He followed suit two years later, first finding work with the Department of Lands and Survey before being employed as a radiographer at the Taranaki Base Hospital in New Plymouth where he remained until 1978. A few years later he took up employment with Kea Books, a second-hand bookshop located on Devon St. Barton’s bibliophilic mind was well suited to the work. He spent the rest of his working career there and retired as manager in 1991.

The bequest comprised 20 books printed during the 15th and early 16th centuries. Theology is the most prevalent subject, with the earliest publication being a collection of Pseudo-Augustinian tracts (shown here) printed in the town of Lauingen, Germany, in 1472 - one of only two titles printed in Lauingen during the 15th century. It is a remarkable little book typographically, as its roman type is one of the earliest produced in Germany and is unique to this edition.

Cataloguing of the collection is nearing completion and the books will soon be available for study.

Pseudo-Augustine, De anima et spiritu. Add: De ebrietate. De sobrietate. De quattuor virtutibus caritatis. De contritione cordis. [Lauingen: Printer of Augustinus, ‘De consensu evangelistarum’], 9 Nov. 1472, Alexander Turnbull Library, R407716.

Post link

Currentlyon view in our special collections is the first topographical view of a city in the Liber Cronicarum, this of Jerusalem, along with the page spread on the verso of this leaf which shows the construction of the Tower of Babel. This week only, these two page-spreads from our two Latin editions of the Nuremberg Chronicles; next week, new leaves, new views…

Post link

#TypographyTuesday: Anton Koberger was one of the most successful printers of the late 15th and early 16th centuries.⠀ ⠀ BX1308 .A3 1496⠀ ⠀ #antonkoberger #romantype #typography #bibliophile #bookstagram #booklover #rarebooks #specialcollections #librariesofinstagram #iglibraries #mizzou #universityofmissouri #ellislibrary #ifttt

Typography101 #1

Post link