#john william waterhouse

Some day I want to paint like Waterhouse. Until then I guess there’s fancy brushes and texture overlays in photoshop.

Post link

(A Mermaid, 1900/ John William Waterhouse; 1849-1917)

Circe Offering the Cup to Odysseus by John William Waterhouse

Miss Margaret Henderson (1900), by J.W. Waterhouse

The Alexander Henderson family was of considerable importance at the turn of the century. He had gained a fortune by investing in real estate and the railway industry and together with two of his sons, they used their wealth for buying prominent art. Waterhouse became befriended with them, which resulted in several commissions and some people argue that all his later works were made to please the family. The portrayed figure is probably the 21-year old daughter, although no other images from her are known to exist and little is known about her life. Nowadays it is hard to imagine how patriarchal society was in those days.

The portrait is in many ways traditional: its warm colours against a dark background and the probably idealized beauty of the subject. Waterhouse gave it a personal touch by adding the rose to the garment. The expression of the woman, with a touch of fear, suggests her mind is with much bigger subjects than posing for a 30 years older painter.

Post link

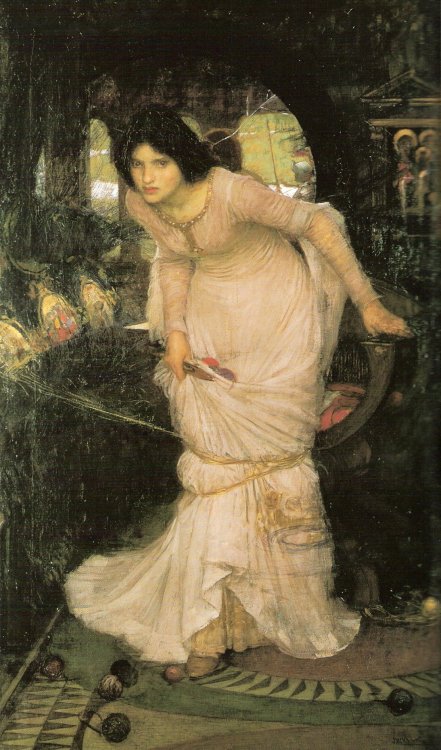

The Lady Clare (1900), by J.W. Waterhouse

Waterhouse was a fan of Alfred Tennyson and used his poems as subject for several of his paintings. The poem with the same title as this painting was published in 1842 (together with The Lady of Shalott and Mariana in the South) and describes the victory of true love over class. Lady Clare appears on her wedding day in a peasant’s dress to reveal her poor heritage to her rich lover – Waterhouse liked to paint women taking destiny in their own hands. Fortunately, Lord Ronald decides to marry her anyway so this story has a happy ending.

The painting was exhibited to support impoverished colleagues and raised £450 when it was sold to the barrister Ernest Moon.

The Lady Clare

It was the time when lilies blow,

And clouds are highest up in air,

Lord Ronald brought a lily-white doe

To give his cousin, Lady Clare.

I trow they did not part in scorn-

Lovers long-betroth’d were they:

They too will wed the morrow morn:

God’s blessing on the day!

‘He does not love me for my birth,

Nor for my lands so broad and fair;

He loves me for my own true worth,

And that is well,’ said Lady Clare.

In there came old Alice the nurse,

Said, 'Who was this that went from thee?’

'It was my cousin,’ said Lady Clare,

'To-morrow he weds with me.’

'O God be thank’d!’ said Alice the nurse,

'That all comes round so just and fair:

Lord Ronald is heir of all your lands,

And you are not the Lady Clare.’

'Are ye out of your mind, my nurse, my nurse?’

Said Lady Clare, 'that ye speak so wild?’

'As God’s above,’ said Alice the nurse,

'I speak the truth: you are my child.

'The old Earl’s daughter died at my breast;

I speak the truth, as I live by bread!

I buried her like my own sweet child,

And put my child in her stead.’

'Falsely, falsely have ye done,

O mother,’ she said, ’ if this be true,

To keep the best man under the sun

So many years from his due.’

'Nay now, my child,’ said Alice the nurse,

'But keep the secret for your life,

And all you have will be Lord Ronald’s,

When you are man and wife.’

'If I’m a beggar born,’ she said,

'I will speak out, for I dare not lie.

Pull off, pull off, the brooch of gold,

And fling the diamond necklace by.’

'Nay now, my child,’ said Alice the nurse,

'But keep the secret all ye can.’

She said, 'Not so: but I will know

If there be any faith in man.’

'Nay now, what faith?’ said Alice the nurse,

'The man will cleave unto his right.’

'And he shall have it,’ the lady replied,

'Tho’ I should die to-night.’

'Yet give one kiss to your mother dear!

Alas, my child, I sinn’d for thee.’

'O mother, mother, mother,’ she said,

'So strange it seems to me.

'Yet here’s a kiss for my mother dear,

My mother dear, if this be so,

And lay your hand upon my head,

And bless me, mother, ere I go.’

She clad herself in a russet gown,

She was no longer Lady Clare:

She went by dale, and she went by down,

With a single rose in her hair.

The lily-white doe Lord Ronald had brought

Leapt up from where she lay,

Dropt her head in the maiden’s hand,

And follow’d her all the way.

Down stepped Lord Ronald from his tower:

'O Lady Clare, you shame your worth!

Why come you dressed like a village maid,

That are the flower of the earth?’

'If I come dressed like a village maid,

I am but as my fortunes are:

I am a beggar born,’ she said,

'And not the Lady Clare.’

'Play me no tricks,’ said Lord Ronald,

'For I am yours in word and in deed.

Play me no tricks,’ said Lord Ronald,

'Your riddle is hard to read.’

O and proudly stood she up!

Her heart within her did not fail:

She look’d into Lord Ronald’s eyes,

And told him all her nurse’s tale.

He laugh’d a laugh of merry scorn:

He turn’d and kiss’d her where she stood:

'If you are not the heiress born,

And I,’ said he, 'the next in blood-

'If you are not the heiress born,

And I,’ said he, ’ the lawful heir,

We two will wed to-morrow morn,

And you shall still be Lady Clare.’

Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Post link

A Mermaid (1900), by J.W. Waterhouse

Ever after he we was elected as member of the Royal Academy of Arts, Waterhouse studied on a Diploma Work. Sketches dating back to 1892, finally resulted in this work that was donated in 1901. The young woman’s desire of human love, the attention to her hair and the association with water can be traced all the way back to one of Waterhouse’s earliest paintings (Undine in 1872).

Mermaids were a very popular theme in English art after Hans Christian Andersen wrote his fairy tale “The Little Mermaid” in 1836.

Post link

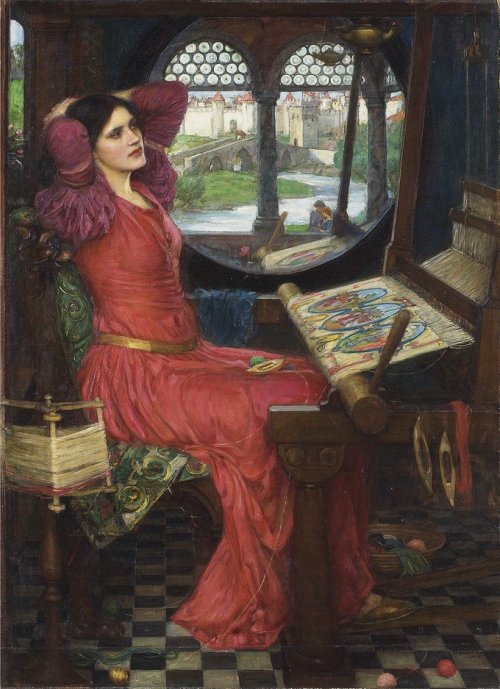

Destiny (1900), by J.W. Waterhouse

This work was painted by Waterhouse to support the injured soldiers and widows of the British army that fought in the Boer War against South African rebels (1899-1902). More than 300 artworks were sold for a total of 12,000 pound sterling.

The work resembles the 1894 version of The Lady of Shalott, but the red and white dress and blue cup represent the colours of the Union Jack, clearly stating that this is a British lady looking at a departing army that is visible in the mirror.

Post link

Mrs Arthur Kenworthy (ca. 1899), by J.W. Waterhouse

Waterhouse was not famous because of his portraits, but towards the end of his life he painted more and more of them. It is a first sign of the general public losing interest in his works. His later paintings were sold at lower prices, so Waterhouse relied on commissions for extra income. The appointed portraits however needed to resemble the sitter, whereas Waterhouse preferred to show his ideals of female beauty on the canvas.

This is the portrait of his wife’s sister in law: Louise. She was married to Arthur Kenworthy. Whether it was painted as a gift or for a commission is not known.

In 1900, Esther and John William Waterhouse moved from the studio on Primrose Hill to 10, Hall Road in St. John’s Wood in the City of Westminster. It was the former home of the sculptor and co-member of the Art Workers Guild: Harry Bates, who had died in 1899.

Post link

The Awakening of Adonis (1899), by J.W. Waterhouse

Adonis was commissioned to the underworld by Zeus, but every spring, when the anemones start to flower, he is kissed back to life by his lover Aphrodite. To the right, we see Cupid reviving the glowing torch of life and Waterhouse’s favourite birds, the pigeons also fly into the scene.

Already during his life, the painting was criticized for being too mellow and also the technique does not match Waterhouse’s usual standards. It may have been rushed to be finished in time for the 1899 summer exhibition of the Royal Academy. Andrew Lloyd Webber added it to his art collection in 2016.

Post link

Juliet (1898), by J.W. Waterhouse

This lovely portrait of Shakespeare’s Juliet in a Venetian setting with a canal and a bridge in the background is also known as The Blue Necklace. Like so many of the Early Renaissance Italian painters, Waterhouse shows the girl in a perfect profile to display her exceptional beauty.

The painting always resided in private collections of which Sir Frederick Morris Fry, a member of the Council of the City and Guilds of the London Technical Institute and master of the notable Merchant Taylors’ School, was the first. During his life he gathered a collection of at least five paintings by Waterhouse.

Post link

Flora and the Zephyrs (1898), by J.W. Waterhouse

Again based on Ovidius, Flora is the Roman goddess of spring, flowers and nature. Here she is shown being kissed on her arm by Zephyrus, the god of the benevolent western wind, who has brought his disciples: the Zephyrs. The god traps Flora in a chain of white roses.

The most famous depiction of the same scene is the Primavera from Botticelli. Besides the seduction, Botticelli also showed the pregnancy of Flora. She is therefore also the goddess of new life. Waterhouse highlighted that by the voluptuous breasts, which are well exposed by Flora’s raised arms.

The painting was commissioned by George McCulloch, a retired businessman who made a fortune in Australian silver mining.

Post link

Ariadne (1898), by J.W. Waterhouse

Another painting based on the 21 letters from Ovidius, collectively known under the name Heroides. The story of Ariadne is most renowned from her helping her beloved Theseus to kill the Minotaur and escape out of the labyrinth that her father had built. She did this by giving him a ball of thread so that he could find his way back. Here she is shown sleeping on a bench, while her lover is leaving her behind and sails away. The two panthers represent the god Dionysus who seduces her and makes her his wife.

In the Vatican Museum, there is a marble Hellenistic sculpture showing Ariadne in almost the same pose as on this painting. Waterhouse must have used it as a model. There are also obvious resemblances with the painting of Saint Cecilia (1895): the ship in the background, the balustrade separation and the sleeping woman to name just a few. In 1895, there was a large exhibition of Venetian art in London and its effect on his paintings is undeniable. Waterhouse becomes more and more influenced by the paintings of Botticelli and other works from the Italian Renaissance.

Post link

Mariana in the South (1897), by J.W. Waterhouse

This painting of Mariana refers again to a poem by Tennyson, this time published in 1830 (see below). The character originates from Shakespeare’s “Measure by Measure” in which Mariana withers by loneliness as her lover, Duke Angelo, chases another woman.

With blackest moss the flower-plots

Were thickly crusted, one and all:

The rusted nails fell from the knots

That held the pear to the gable-wall.

The broken sheds look’d sad and strange:

Unlifted was the clinking latch;

Weeded and worn the ancient thatch

Upon the lonely moated grange.

She only said, ‘My life is dreary,

He cometh not,’ she said;

She said, 'I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!’

Her tears fell with the dews at even;

Her tears fell ere the dews were dried;

She could not look on the sweet heaven,

Either at morn or eventide.

After the flitting of the bats,

When thickest dark did trance the sky,

She drew her casement-curtain by,

And glanced athwart the glooming flats.

She only said, 'The night is dreary,

He cometh not,’ she said;

She said, 'I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!’

Upon the middle of the night,

Waking she heard the night-fowl crow:

The cock sung out an hour ere light:

From the dark fen the oxen’s low

Came to her: without hope of change,

In sleep she seem’d to walk forlorn,

Till cold winds woke the gray-eyed morn

About the lonely moated grange.

She only said, 'The day is dreary,

He cometh not,’ she said;

She said, 'I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!’

About a stone-cast from the wall

A sluice with blacken’d waters slept,

And o'er it many, round and small,

The cluster’d marish-mosses crept.

Hard by a poplar shook alway,

All silver-green with gnarlèd bark:

For leagues no other tree did mark

The level waste, the rounding gray.

She only said, 'My life is dreary,

He cometh not,’ she said;

She said, 'I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!’

And ever when the moon was low,

And the shrill winds were up and away,

In the white curtain, to and fro,

She saw the gusty shadow sway.

But when the moon was very low,

And wild winds bound within their cell,

The shadow of the poplar fell

Upon her bed, across her brow.

She only said, 'The night is dreary,

He cometh not,’ she said;

She said, 'I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!’

All day within the dreamy house,

The doors upon their hinges creak’d;

The blue fly sung in the pane; the mouse

Behind the mouldering wainscot shriek’d,

Or from the crevice peer’d about.

Old faces glimmer’d thro’ the doors,

Old footsteps trod the upper floors,

Old voices call’d her from without.

She only said, 'My life is dreary,

He cometh not,’ she said;

She said, 'I am aweary, aweary,’

I would that I were dead!’

The sparrow’s chirrup on the roof,

The slow clock ticking, and the sound

Which to the wooing wind aloof

The poplar made, did all confound

Her sense; but most she loathed the hour

When the thick-moted sunbeam lay

Athwart the chambers, and the day

Was sloping toward his western bower.

Then, said she, 'I am very dreary,

He will not come,’ she said;

She wept, 'I am aweary, aweary,

O God, that I were dead!’

Post link

Pandora (1896), by J.W. Waterhouse

Because Prometheus had stolen the fire from Mount Olympus, Zeus punished mankind by creating Pandora. She was sent to earth with a jar that was not to be opened. But man’s thirst for knowledge was too strong and when she opened the box, sickness, death and all other of world’s evils escaped.

In a jar an odious treasure is

Shut by the gods’ wish:

A gift that’s not everyday,

The owner’s Pandora alone;

And her eyes, this in hand,

Command the best in the land

As she flits near and far;

Prettiness can’t stay

Shut in a jar.

Someone took her eye, he took

A look at what pleased her so

And out came the grief and woe

We won‘t ever be rid of,

For heaven had hidden

That in the jar.

In the works of Waterhouse in the 1890’s, the somewhat cold classicism was gradually replaced with a warmer English version of symbolism that some even call a late outburst of romanticism.

Post link

Hylas and the Nymphs (1896), by J.W. Waterhouse

Hylas is a character from Greek and Roman mythology as recorded in the Metamorphoses by the poet Ovidius. Whereas in 1893, Waterhouse painted only one nymph approaching the sleeping Hylas, we see here a group of seven water nymphs (naiads) surprising Hylas when he is filling his jar with water from the pond. The nymphs all have very similar faces to stress that they are no ordinary human beings. Their erotic desire makes them lure Hylas into the pond where he will drown. Waterhouse had a fascination for strong, but fatal women associated with water. One can only guess what this is based on.

In 2018, this painting attracted a lot of media attention when the Manchester Art Gallery moved it out of public display as a move “against the objectification and exploitation of women”. After a storm of protests against this form of censorship, the Manchester City Council ordered that the painting should be moved back in its original position.

Post link

The Shrine (1895), by J.W. Waterhouse

With this painting (top) Waterhouse returned to an old theme, which he last painted in 1890 (A Roman Offering, bottom). The stairs, flowers, a young woman – most traditional ingredients are there. Only the doves are absent …

The Victorian dress is sometimes referred to as an anachronism, but in fact there is no suggestion that Waterhouse wanted to paint a Roman scene. It can just as well be a garden in Victorian times. Waterhouse has often tried to paint the five senses. Here he is particularly successful with the sense of smell.

Post link