#medieval art

giraffe

travel miscellany (based on John Mandeville), Saxony 15th century

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Ms. germ. fol. 204, fol. 140r

Post link

multicolored cats

Worksop Bestiary, England c. 1185

NY, The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.81, fol. 46v

Post link

medieval facepalm

(drunken Noah, Ham, Shem and Japheth, Genesis 9:20-24)

Biblia Pauperum, Netherlands c. 1395-1400

BL, Kings 5, fol. 15r

Post link

hedgehog

Worksop Bestiary, England c. 1185

NY, The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.81, fol. 10v

Post link

snail hunt

Livre des merveilles du monde, France c. 1460

NY, The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M.461, fol. 78r

Post link

frozen souls

(Inferno XXXII)

Dante Alighieri, Divina Commedia, Italy ca. 1420-1430

BnF, Italien 74, fol. 95r

Post link

To Know How to Look Upward

The Cathedral Church of Saint Peter in Exeter (Devon, South West England, United Kingdom).

The monument was built between the 12th and the 13th century, in the style of Norman Gothic. Architecturally, the building has several notable features, as an early set of misericords, an astronomical clock and the longest uninterrupted vaulted ceiling in England.

(The photographs show, in order: the Lady Chapel, original photograph by David Iliff ; the nave, idem ; the facade, original photograph by Torsten Schneider ; the east window in Lady Chapel, original photograph by DeFacto ; the organ, original photograph by Karl Gruber ; the east window again, original photograph by Discovery1412 ; the nave, original photograph by David Iliff ; the ceiling, original photography by DeFacto ; The Great East Window, idem ; and finally, the astronomical clock, ditto. The original photographs have been modified)

The Most Poetic

The St. Andrew’s Cathedral in Wells, (Somerset, England).

Built between 1180 and 1490, this cathedral mixes different currents of English Gothic architecture.

One of the major architectural innovations of this building is the addition in the 14th century of inverted arches known as “scissor arches”, at the level of the transept crossing. This technique, which breaks the monotony of the traditional sequences of ogival arches, permits to better distribute and support the weight of the bell tower which rises at this location, while consolidating the entire structure.

(The photographs show, in order: the Lady Chapel, photograph by David Iliff ; the inverted arch, idem ; the facade at sunset, photograph by StuJoPhoto ; the arches, photograph by Gary Ullah ; the organ, photograph by David Iliff ; the bell tower, photograph by Prosthetic Head ; the nave, photograph by David Iliff ; detail of the facade, photograph by Hadrianus1959 ; the facade, photograph by Michael D Beckwith ; and finally, the vault, photograph by Texasrancher99. The original photographs have been modified)

Metamorphosis

The Saint-Maclou cathedral of Pontoise, (Val-d'Oise, Île-de-France, France).

Having the status of cathedral since 1966, this Gothic monument was built in the twelfth century. Given its initial nature as a church, the building has modest dimensions and including a very narrow transept. Elements of the Renaissance style will be added in the 16th century, such as side chapels, while the symmetry of the building will be broken.

Today, magnificent capitals and Romanesque keystones are still observable, while the cathedral contains remarkable religious sculptures.

(The photographs show, in order: the western facade, photograph by BastienM ; capitals of the southwest corner of the transept crossing, photograph by Pierre Poschadel ; altarpiece of the first chapel in front of the south aisle, idem ; the nave and the organ, photograph by BastienM ; funerary slab of Jean Desmons, doctor, died in 1695, photograph oby Pierre Poschadel ; the collateral north of the nave, idem ; La Charité, by Granier for the tomb of François de Guénégaud, sculpture made around 1688, idem ; the choir, idem ; south aisle, pilaster between 4th and 5th span, idem ; and finally, sculpture representing the Christ, Joseph of Arimathea, Madeleine, and John consoling the Virgin Mary, idem)

“Edinburgh would not be Edinburgh without it”

- Cameron Lees (1835-1913)

The Saint Giles’ Cathedral of Edinburgh, Scotland.

Built from the 12th century, many great and famous elements of this gothic monument will be added later, as the distinctive crown steeple, over the crossing, installed around 1490, while this spire is now one of the most known Edinburgh’s landmarks.

(The pictures show, in order: a global exterior view, original photograph by Carlos Delgado ; the blue screen inside new west porch, original photograph by Enchufla Con Clave ; a view on the nave, idem ; a view on the arcades, original photograph by Leandro Neumann Ciuffo ; the Thistle Chapel, original photograph by Enchufla Con Clave ; the crown steeple, original photograph by Stephencdickson ; detail of a stained glass window representing the Christ commanding the sea to be still, original photograph by Amy Mantravadi ; an interior view, original photograph by Enchufla Con Clave ; the nave, original photograph by Michael D Beckwith ; and finally, the sculptures above the west door, original photograph by Nilfanion. The original photographs have been modified)

Almost done! This week has been a good one, self improvement and pushing my skills to the limit. It’s only getting better from here.

HISTORY IN COLOR

Ultramarine

RGB: (18, 10, 143)Closest Pantone match: 2746 C

The name Ultramarine comes from the latin ultramarinus, meaning “beyond the sea”. During the 14th and 15th centuries, Ultramarine arrived in Europe through shipments coming from the mines of what is today Afghanistan. These mines produced the deep blue, semiprecious mineral lapis lazuli which was ground into a powder to make Ultramarine.The process was exhaustive, as it yielded only a small quantity of dye, and all but the finest stones produced a drab, washed-out color.

Due to its rare, precious origin and the costs of its production and shipment, the price of Ultramarine in Europe was exorbitant. During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance it was most often used in Christian art, tinting Mary’s robes the color of purity. As it was distributed through Italy, art using Ultramarine is rarer in the northern parts of Europe.

In 1824, the Societé d'Encouragement pour l'Industrie Nationale in France offered a prize to whomever could replicate the hues of Ultramarine through artificial means. The german chemist Christian Gmelin published his method of doing so in 1826, which led to one of the names for artificial Ultramarine being “Gmelin’s color”.

Post link

Noli me Tangere, Master of the Lehman Crucifixion (Jacopo di Cione?), between 1368 and 1377

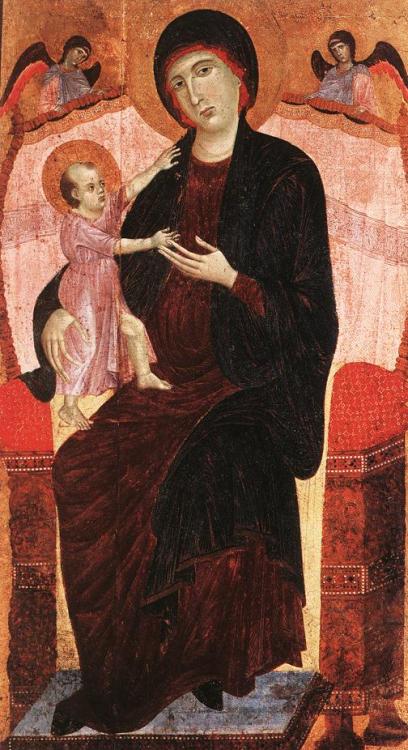

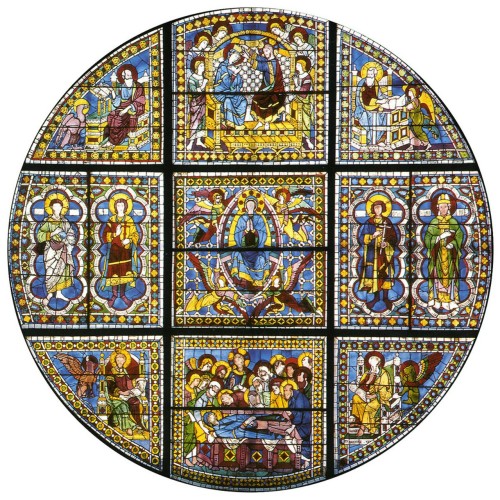

AN INCOMPLETE HISTORY OF MEDIEVAL ART V: The Social and Material Contexts of Duccio’s Rucellai Madonna

In 1285, the Florentine confraternity of the Laudesi comissioned the workshop of Duccio di Buoninsegna to paint an image of the Virgin and Child for the chapel they sponsored in the church of Santa Maria Novella. Like the other urban confraternities, the Laudesi provided care and services for each other at the time of a member’s demise, overseeing funeral rites, financially assisting surviving family members and collectively praying for the soul of the deceased. The latter took the form of laude, or hymns sung by the group in praise of the Virgin, begging her intercession on behalf of the defunct member. The lauds and other confraternity activities were performed in the group’s chapel, under the supervision of the Dominican friars. The panel painting of the Virgin and Child commissioned of Duccio was, therefore, was destined to serve as the visual focus of a devotional, musical performance by a prestigious, civic-minded group, conducted in a large stone-vaulted chapel.

In 1260, city-state of Siena defeated its long-standing rival Florence at the battle of Montaperti. This victory was attributed to the intervention of the Virgin, to whom the city of Siena had been dedicated the previous day. In the years following the battle, increased demand for representations of the Queen of the City caused Sienese artists to develop, elaborate and refine new Marian pictorial types and conventions. Thus, in 1285, Siena was where one went for high-quality, modern pictures of the Virgin by experienced artists, and Duccio was an established master painter of such images in that city. This fact must have complicated the prominent Florentine confraternity’s decision to choose Duccio over a local painter and indicates that the Sienese painter’s artistic reputation not only trumped even bitter, tenaciously-held political rivalries, but that it was more important to the Laudesi to have the best image of the Virgin available than it was to rehearse partisan loyalties.

The negotiations between artist and client are preserved in the contract, drawn up on 15 April 1285 and preserved in the archive at Santa Maria Novella. The contract stipulates that Duccio will paint an image in the Virgin and Child and angels on a panel previously prepared by a carpenter in return for the amount of 150 lire (approx. 91 florins). The confraternity had the right of refusal without payment “if the image did not please.” The contract does not specify anything about the style of painting, and no details of composition are mentioned, but it clearly enjoins the artist to use real gold for the background and genuine azzurro, the hugely expensive blue pigment made from ground lapis lazuli, for the large expanse of the Virgin’s robe. The expense of both materials was to be covered by the artist. The contract also states that the painting of the figures will be carried out by Duccio, and not by, one presumes, less-qualified workshop assistants. No delivery date is specified. Thus, at the level of the contract, what we think of as aesthetic issues are not mentioned at all. The value equivalent to 150 lire to be created by Duccio would lie in the conspicuous use of high-quality materials and the registration of the master’s hand in the work—preciousness and authority. These are the values one encounters again and again in medieval documents concerning the commission and/or evaluation of works of art, and they give us some sense of the period expectations viewers brought to the experience of looking at pictures.

TheRucellai Madonna is the largest 13th-century panel painting to survive.

The image of the Rucellai Madonna is accompanied by other pictures of the Virgin and Child by Duccio.

AN INCOMPLETE HISTORY OF MEDIEVAL ART:

I: Saint Denis and Gothic Art

II: The Carolingian Renovatio

III: The Monastic Scriptorium

IV: Grisaille, or The Abstention from Color

V: The Social and Material Contexts of Duccio’s Rucellai Madonna

VI: Beauvais Cathedral and the Limits of Gothic Verticality

VII: The Harrowing of Hell

VIII: The Sutton Hoo Ship Burial

IX: The Art of the Dark Ages

X: Simone Martini’s Saints

XI: Sainte-Foy de Conques

XII: The Cave Churches of Cappadocia

XIII: The Klosterneuburg Altar

Post link

ohn Uskglass, the Raven King crowned in ivy (in its entirety) by Soni Alcorn-Hender From Susanna Clarke’s book: Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell Pencil and acrylics, old paper, and digital.

Available here: http://www.redbubble.com/people/bohemianweasel/works/16013490-raven-king-in-ivy-1

Post link