#linguistic maps

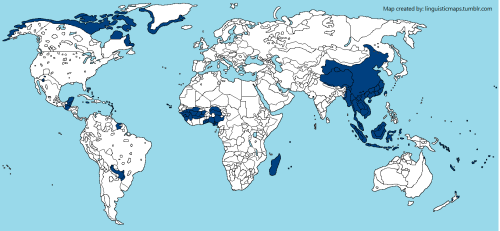

Aspirated plosives

Aspirations occurs in English in initial onsets like in ‘pat’ [pʰæt], ‘tack’ [’tʰæk] or ‘cat’ [’kʰæt]. It is not phonemic, since it doesn’t distinguish meanings, but it’s distinctive in Mandarin e.g. 皮 [pʰi] (skin) vs. 比 [pi] (proportion).

Non-phonemic aspiration occurs in: Tamazight, English, German, Swedish, Norwegian, Kurdish, Persian, Uyghur.

Phonemic aspiration: Sami languages, Icelandic, Faroese, Danish, Mongol, Kalmyk, Georgian, Armenian, North Caucasian languages, Sino-Tibetan languages, Hmong-Mien languages, Austroasiatic languages, Hindi-Urdu, Punjabi, Marathi, Gujarati, Odya, Bengali, Nepali, Tai-Kadai languages, Nivkh, many Bantu languages (Swahili, Xhosa, Zulu, Venda, Tswana, Sesotho, Macua, Chichewa, and many Amerindian languages (Na-Dene, Siouan, Algic, Tshimshianic, Shastan, Mayan, Uto-Aztecan, Mixtec, Oto-Manguean, Quechua, Ayamara, Pilagá, Toba, etc.)

Post link

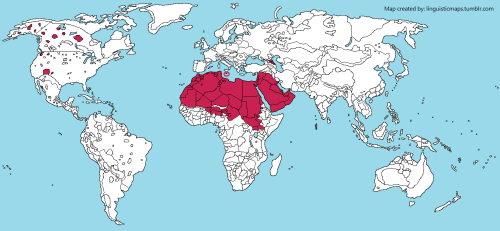

Glottal Stop

Languages that have a phonemic glottal stop /ʔ/ - about 40% of all human languages. This is a very widespread consonant except in Indo-European, Niger-Congo, Turkic, Uralic, Mongolic, Dravidian, Koreanic and Japonic languages.

It’s almost universally present in the indigenous languages of the Americas, in Afro-Asiatic languages, in Austroasiatic and Austronesian languages, in Papuan languages, North Caucasian langauges, and in some Khoe, Sino-Tibetan, Daic, Uralic, Iranian, Turkic and Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages. It’s also present in Estuary and Scouse English as in ‘watter’ as /woːʔɐ/.

Post link

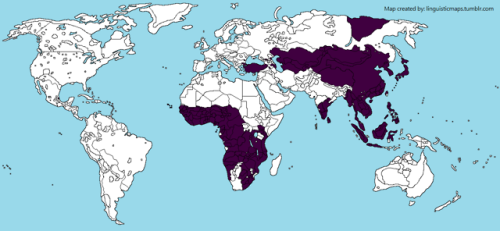

Tenseless languages

Language that do not possess the grammatical category of “tense”, although obviously, they can communicate about past or future situations, but they do it resorting to adverbs (earlier, yesterday, tomorrow), the context (pragmatics), but mostly aspect markers, that show how a situation relates to the timeline (perfective, continuous, etc.) or modal markers (obligation, need, orders, hipothesis, etc.)

Tenseless languages are mostly analytic/isolating, but some are not. They occur mainly in East and Southeast Asia (Sino-Tibetan, Austroasiatic, Austronesian, Kra-Dai, Hmong-Mien), Oceania, Dyirbal (in NE Australia), Malagasy, Yoruba, Igbo, Hausa, Ewe, Fon and many Mande languages of Western Africa, most creole languages, Guarani, Mayan languages, Hopi, some Uto-Aztecan languages, and Greenlandic and other Inuit dialects.

Post link

Prefixing and suffixing languages

- Mostly prefixing - Most Berber languages, Bantu languages, Guarani, many Macro-Ge languages, Mayan languages, Oto-Manguean, Mixtec, Siouan, Navajo and many Na-Dene languages, some languages in northwest Papua and northwest Australia.

- Mostly suffixing - Indo-European, most Afro-Asiatic, Turkic, Mongolic, Dravidian, Austronesian, Northeast Caucasian, Eskimo-Aleut, Uralic, Koreanic-Japonic, most Pama-Nyungan languages.

- Equally prefixing and suffixing - Cree, Ojibwe, O’odham, Tarahumara, Pilagá, Carib, Central Atlas Tamazight, Tuareg, Iraqi Arabic, Zande, Krio languages, Ewe, Toba, many languages in east Papua-New-Guinea, Basque, Nortwest Caucasian, Celtic.

- Little affixation - typical of isolating languages, in Sino-Tibetan, Austroasiatic, Hmong-Mien, Nilo-Saharan, Mande, languages of West Africa, many Austronesian languages.

Based off and simplified from: https://wals.info/feature/26A#2/22.6/153.1

Post link

Pronounciation of the digraph <OU>

- [ow] - Spanish (very rarely), Northern European Portuguese and formal register of Brazilian Portuguese, Galician, Catalan, Romanian, Czech, Slovak, Finnish, Karelian, Estonian, Sami languages.

- [o] - Portuguese (European, and informal Brazilian)

- [ɔw] - Somali, Occitan, Catalan and Flemish.

- [əw] - Afrikaans, Europen Portuguese (Oporto city region).

- [aw] - Dutch.

- [u] - French (also for /w/), Breton, Cornish, and Greek, shown here for comparison althoug it is more precisely <ου> (o+ipsilon).

- [aʊ, ʌ, oʊ/əʊ, ʊ, u:] - English as in <out>, <trouble>, <soul>, <could> and <group>, respectively.

Maybe I missed a few languages that use <ou>; if you know any more, point them out, please.

Post link

Relativization strategies

How do languages form relative clauses like “the man that ate bread went home”.

- Relative pronoun/particle/complementizer - “the man [that/whoate bread] went home”. Typical of Indo-European, Uralic and Semitic languages.

- Correlative relative (non-reduction) - “the man [who ate bread], [that man] went home or “the man [he ate bread] went home” - this strategy involves an anaphor, repeating the antecedent with a noun/pronoun. Pronoun retention is also lumped in here. This strategy occurs in Indo-Aryan languages (Hindi, Bengali, Punjabi, Gujarati, Marathi, etc.), in Mande languages (e.g Bambara in Mali), Yoruba, Lakhota, Warao, Xerente, Walpiri, etc.

- Nominalized/participial relative - “the [bread eating] man went home” or “the [bread eaten] man went home” - I lumped this two together because the behaviour is very similar - used in Turkic, Mongolic, Koreanic, Dravidian, and Bantu languages.

- Genitive relative - “[ate bread]’s man went home" - used in Sino-Tibetan, Khmer, Tagalog, Minangkabau, and Aymara.

- Relative affix - “the man [ate-REL bread] went home” - used in Seri, Northwest and Northeast Caucasian languages and Maale (Omotic).

- Adjunction - “the man [ate bread] went home”, with no overt marker just justapositions modifying the main clause. Used in Japanese, Thai, Shan, Lao, Malagasy.

- Internally headed relative - "[the man ate the bread] went home", the nucleous is in the relative clause itself. Used in Navajo, Apache, Haida.

If you know about the languages left in blank, please let me know!

Post link

Nonconcatenative morphology

Nonconcatenative morphology, also called discontinuous morphology and introflection, is a form of word formation in which the root is modified and which does not involve stringing morphemes together sequentially.

It may involve apophony (ablaut), transfixation (vowel templates inserted into consonantal roots), reduplication, tone/stress changes, or truncation.

It is very developed in Semitic, Berber, and Chadic branches of Afro-Asiatic. It also occurs extensively among other language families: Nilo-Saharan, Northeast Caucasian, Na-Dene, Salishan and the isolate Seri (in Mexico).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nonconcatenative_morphology

Post link

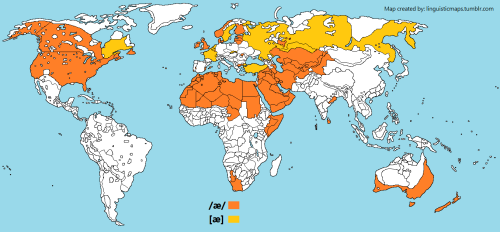

(near) Open/low front unrounded vowel

This is the vowel used in English “sad”. It exists as an allophone of other vowels in Turkish, Russian, Dutch, Slovak, Swedish and French (as a nasal vowel).

Phonemically, it exists in English, all Arabic languages/dialects, all Berber languages, Somali, Afrikaans, Norwegian, Finnish, Estonian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Danish, Kurdish, Azeri, Persian, Qazaq, Uzbek, Turkmen, Uyghur, Bashkir, Orya, Sinhalese, and in some dialects of Portuguese, Andalusian Spanish, Greek, Romanian.

Post link

Light verb constructions

A light verb is a verb deprived of its basic meaning. Many languages employ them in extensive constructions of verb+noun, instead of forming new verbs.

In English, the verb “make” can be a light verb, as in “make the bed”. It doesn’t mean that you are going to literally “build a bed”. But in many languages these constructions are the norm for new verbs that enter the language and are extremely common.

In many languages, like Basque, Persian, Hindi, or Japanese, instead of “to clean” one can have “do cleaning”, or instead of “to speak”, “to make talk”, or instead of “to hug”, “to give hug”.

A light verb is in the midway between a full lexical verb and an auxialiry verb. In English a few verbs can function as light verbs (do, make, give, take, have) but these constructions are not the norm.

If you know more languages that use these constructions frequently (I’m not sure about Turkic languages), please inform me.

Post link

Languages where 3rd person singular pronouns are the same or derived from demonstrative determiners

For example, “o” in Turkish is both “he/she/it” and “that”.

Source: https://wals.info/feature/43A#3/32.99/28.92

Post link

Comparative constructions

Ex: “My father is older than my mother”.

Types:

1. Locative comparatives: “From my mother, my father is old” - a movement pre/postposition or case like “from, to, at, on, for” (includes genitive constructions).

2. Exceed comparatives: “My father old exceed my mother” - a verb meaning “to exceed” or “to surpass”.

3. Conjoined comparative: “My father old, my mother young” - two clauses, with antonyms or a negation of the opposite, or just justaposition of the terms.

4. Particle comparative: “My father is older than my mother” - particle “than” with or without a marker on the adjective.

Some languages use a mixed strategy, like Russian, Romanian, Portuguese or Italian. Only the most used strategy is shown in some cases.

Source: https://wals.info/chapter/121

Post link

Languages that use “ciao” or a similar version descended from Italian as a greeting or an informal goobye

Present in: Portuguese (tchau), Spanish from Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Paraguay, Colombia, Venezuela, Panama, Costa Rica, Catalan, Sicilian, Maltese, Venetian, Lombard, Romansh, German (tschau), Swiss German, every Slavic language except Polish and Belarussian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Estonian (tsau), Greek, Albanian (qao), Romanian (ceau), Hungarian (csaó), Somali, Amharic, Tigrinya, Malaysian. The Vietnamese “chào” is not related to Italian, so it’s unmarked there.

Edit: the map only includes those languages that use ‘ciao’ as the most common informal way of greeting/goodbye, not as part of slang, argots or people who use it just to sound cool. For example, in Portuguese, Maltese or Latvian it has surpassed the older forms of saying goodbye in informal situations for all social classes.

Post link

Ideophones

Ideophones are a word class (part of speech) that occur independently in some languages, mostly in Africa and in Asia. They can be quite extensive, like nouns and verbs, or they can be a small class.

Ideophones are words which exhibit sound symbolism, are iconic, can involve onomatopoeias, and are frequently used in narrations, frequentely reduplicated, and show moods, states, forms, colours, movements, etc. They differ from interjection by the sound symbolism and non-isolate distribution (unlike interjections, which can stand alone like “ouch”).

Japanese is a good example:

doki doki (ドキドキ) — heartbeat: excitement

kira kira (キラキラ) — glitter

shiin (シーン) — silence

niko niko (ニコニコ) — smile

Jiii (じ-) — stare

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ideophone

If you know more languages that use ideophones, please let me know, because there’s relatively few literature about this. Be aware that not all onomatopoeias are ideophones, though.

Post link

Nasal harmony

Nasal harmony is a tendency for assimilation of other consonants and vowels to the nasality of a neighbouring nasal vowel or nasal consonant. For exemple in Guaraní certain affixes have alternative forms according to whether the root includes a nasal (vowel or consonant) or not. For example, the reflexive prefix is realized as oral je- before an oral stem like juka “kill”, but as nasal ñe- before a nasal stem like nupã “hit”. The ã makes the stem nasal.

Nasal harmony occurs in many South American languages like Guaraní, other Tupi languages, Emberá, Otomi languages, Chibchan languages (e.g. Ngäbere) and some Bantu languages (like Umbundu and Kimbundu).

These languages are mainly in central and South America and in Africa. If you know other languages that exhibit this phenomenon please let me know!

Post link

Orthographic depth

Languages have different levels of othographic depth, that means that a language’s orthography can vary in a spectrum of a very irregular and complex orthography (deep orthography) to a completely regular and simple one (shallow orthography).

English, French, Danish, Swedish, Arabic, Urdu, Tibetan, Burmese, Thai, Khmer, Lao, Chinese, and Japanese have orthographies that are highly irregular, complex and where sounds cannot be predicted from the spelling. These writing systems are more difficuld and slow to be learned by children, who may take years. In the medium of the scale there’s Spanish, Portuguese, German, Polish, Greek, Russian, Persian, Hindi, Korean, where there are some irregularities but overall the correspondence of one sound to one phoneme is not that bad. At the positive end of the scale there’s Italian, Serbo-Croat, Romanian, Finnish, Basque, Turkish, Indonesian, Quechua, Ayamara, Guarani, Mayan languages, and most African languages (because there were no history of spelling, so a new one of scratch was made as very regular), they all have very simple and regular spelling systems, with usually a one-to-one correspondence between sounds and letters. These are very easily learned by children.

Orthographic depth has several implications for the study of psycholinguistics and the study of language processing and also acquisition of reading and writing by children.

Note: remember that there’s no objective numbering on the three categories I made, there are more than just these three categories, because it works like a spectrum. Three categories were used just as a means for simplification.

Post link

The Latin alphabet digraph <CH>

- [ʃ, ɕ] in Portuguese, Northwestern Mexican Spanish, Southwestern Andalusian Spanish, French, Breton, Norwegian, Danish, Northern and Finland Swedish

- [tʃ, tɕ] in English (excluding the Greek and Latinate pronounciations with [k]), Spanish, Galician, Qazaq, Uzbekh, Vietnamese, Quechua, Aymara, Mapuche, Nahuatl, Otomi, Mixtec, Mayan languages, Q’ich’e, Navajo, Lakhota, Cree, Payute, Shoshone, Salishan languages, Shipibo-Konibo, Othern Amazonian languages, Shona, Chichewa, Bemba, Swahili, and many other eastern african languages

- [x] in Welsh, Netherland’s Dutch, Southern Swedish, Polish, Czech, Slovak, Lithuanian, Afrikaans, Yiddish

- [x~ç] in Flemish and German

- [k] in Catalan (rare, only word finally), Italian, Sardinian, Sicilian, Neapolitan, Venetian, Emilian, Romanian, Vietnamese (only word finally)

- [xᶲ, xʷ, ɧ] in Central Swedish

- [ts] in Occitan

- [k|ʰ] (click sound) in Xhosa and Zulu.

Post link

Pronounciation of the Latin alphabet letter <Ç>

(it includes the Cyrilic letter Ç, which is homographic with the former)

- [s] in Portuguese, French, Catalan and Occitan.

- [tʃ] in Albanian, Friulian, partly in Manx (Çh), Turkish, Kurdish, Azeri, Turkmen, Tatar.

- [θ] in Bashkort.

- [ɕ] in Chuvash.

Post link

Pronounciation of the Latin alphabet letter <U>

It’s pronounced [u] in most orthographies, but in French, Occitan, Azorean and inner-central European Portuguese, Dutch, Afrikaans, Icelandic and Occitan, <u> represents [y]. In Afrikaans it also represents the more common [œ].

In Swedish, Norwegian, Somali, Faroese, Southern Sami, Ume Sami, Maori, Madeiran Portuguese and Californian English it’s central [ʉ].

In English it has a variety of values namely [ʌ] as in “cut”, [juː] as in “music” and [ʊ] as in “put”. Less commons values are: [ɪ] as in “busy” or [ɛ] as in “bury”.

In Northern Welsh it’s [ɨ] and in Southern Welsh it’s [i].

Post link

Present and past perfect auxiliaries

Periphrastic constructions of tense-aspect with auxiliaries is common for modern Indo-European languages. The present perfect (I have eaten) and the past perfect (I had eaten) both use “to have” (possession verb) as an auxiliary. That’s also the case for Portuguese, Spanish (although no longer with a possession sense), Catalan, Icelandic, Norwegian, Danish, Swedish, Greek, Albanian, Bulgarian, Macedonian, Romanian, and Amharic.

Some languages have both “to have” and “to be” depending on the type of the main verb. French, Italian, German and Dutch have “to be” for unaccusative verbs (including reflexive verbs and intransitive motion verbs, etc.) and “to have” for all other verbs.

Slavic languages, Armenian, and Indo-Iranian languages tend to use “to be” for the same effect. Also, many Bantu languages but only for the past perfect.

Some languages use a verb or particle derived from “to finish” or “already”, such as Arabic, Afrikaans, Meithei, Burmese, Karen, Thai, Lao, Khmer, Khmu, Malay, Indonesian, Sundanese, Javanese, Minangkabau, Aceh, Toba, Tagalog.

Note: not all languages share the same meanings when using the present or past perfect of English, even though the literal translations may be the same. In Portuguese “tenho comido” (lit. I have eaten) means “I have been eating [over and over again]”

Post link

We’ve reached the 10 000 followers line, so thank you everyone for the interest, knowledged and suggestions shared with me. To mark the occasion, please let me know some ideas for maps you’d like to see here.

Null object languages

Languages that allow the object to be omitted if it can be recovered from the context. For example in Portuguese:

“Eu fui ver roupas, mas não quis comprar. “

“I went to see clothes, but I didn’t want to buy [them]”

In English you have to add and recover the meaning using a pronoun (them). In Portuguese the object of the verb “comprar” (to buy) can be omitted.

Note that this is different from verb phrase ellision.

If you guys know more languages with this feature (null object) that are not marked, please let me know.

Post link

Plural Marking typology

How languages mark the plural number on nouns.

Many Bantu languages use a prefix system (also with gender).

Most Indo-European languages have suffixes, although the Germanic languages, and, to a lesser extent French, have a mixed strategy that involves apophony/umlaut, and in the case of French, many irregular plurals, that totaly change the pronounciation of the word.

Arabic, Berber, Hebrew, some Nilo-Saharan languages have this mixed strategy with vowel changes in the middle of the words, and suffixes.

Dinka and Nuer (South Sudan) have only a stem change (apophony).

A few African languages just change the tone of the word. French, Tibetan, Burmese, Vietnamese, Khmer, Philippines’ languages and many Polynesian languages, and the Mande languages West Africa, use a particle before the noun, usually. In French this is the definite article la/le vs. les, because the final -s of nouns is not pronounced, so the plural is only noun in the spoken language from this particle.

Indonesian and Malay have full reduplication (orang - person; orang-orang - people).

Many East Asian languages (Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Thai) don’t mark plural at all.

Post link

![Aspirated plosivesAspirations occurs in English in initial onsets like in ‘pat’ [pʰæt], ‘tack’ [’tʰæ Aspirated plosivesAspirations occurs in English in initial onsets like in ‘pat’ [pʰæt], ‘tack’ [’tʰæ](https://64.media.tumblr.com/336a13765fb031784e1593639b0bb427/49a2b1dfe50b20fa-60/s500x750/989e8050d39083e2ca55c99084db868956ce4409.png)

![Pronounciation of the digraph <OU> [ow] - Spanish (very rarely), Northern European Portuguese Pronounciation of the digraph <OU> [ow] - Spanish (very rarely), Northern European Portuguese](https://64.media.tumblr.com/d59b3ffbdcb3f395a34a64913e12b2f4/becbddcc5ea3ae1b-27/s500x750/a2a543cc14367111cf601d0394b32b2d01114ab1.png)

![The Latin alphabet digraph <CH>[ʃ, ɕ] in Portuguese, Northwestern Mexican Spanish, Southwester The Latin alphabet digraph <CH>[ʃ, ɕ] in Portuguese, Northwestern Mexican Spanish, Southwester](https://64.media.tumblr.com/0c0357340580591c5ec0d321deef81d7/tumblr_py0xk1mO191uuqf4fo1_500.png)

![Pronounciation of the Latin alphabet letter <U>It’s pronounced [u] in most orthographies, but Pronounciation of the Latin alphabet letter <U>It’s pronounced [u] in most orthographies, but](https://64.media.tumblr.com/5451afbc4bccadda6ccb7884286e7e53/tumblr_pxox5279XT1uuqf4fo1_r1_500.png)