#black voices

MasterClass Launches Free Offering in Honor of Black History Month • EBONY

“Since 1976, the nation has celebrated the contributions and achievements of Black Americans each February. This commemorative moment in the yearly calendar serves as a reminder of where we’ve been, as well as how far we’ve come. MasterClass, an online education subscription platform, is making a glimpse of that history available to everyone for free this month, releasing a three-part, 54-lesson class entitled “Black History, Black Freedom, and Black Love.”

“Through the insight and wisdom of Jelani Cobb, Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, Angela Davis, Nikole Hannah-Jones, Sherrilyn Ifill, John McWhorter and Cornel West, the complimentary class examines the nature of race relations in America.”

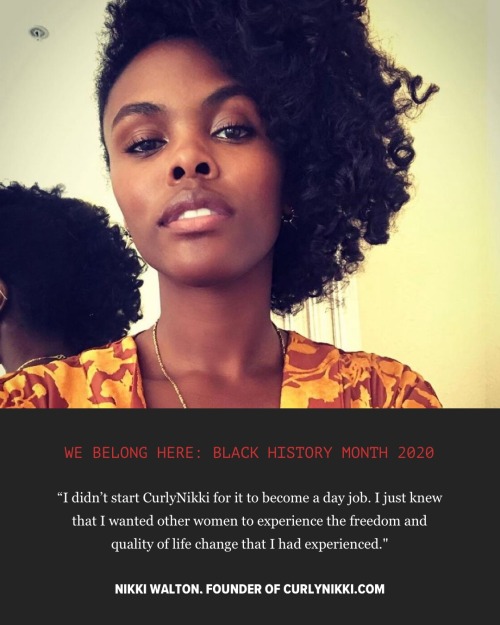

3 Natural Hair Bloggers Reminisce About The Early Days Of The Movement

Nikki Walton, author of “Better Than Good Hair” and “When Good Hair Goes Bad,” helped build and shape the online community around natural hair with her blog CurlyNikki.

“In 2008, I launched CurlyNikki.com with, like, 300 readers from other curl talk and natural hair care forums,” Walton told HuffPost. “I didn’t start CurlyNikki for it to become a day job. I just knew that I wanted other women to experience the freedom and quality of life change that I had experienced. To go from being concerned about my hair 24/7, whether it was for a job interview or graduate school interview or vacation ― the first thought I always had was, ‘What am I gonna do with my hair?’ To be able to help women get over those hurdles and see past their families while they stood firm in their own self-confidence, that is what I wanted to help people do.”

Over the last 20 years, women have found advice and sisterhood in the network of blogs, social media accounts and YouTube channels focused on Black hair. For our Black Hair Defined project, we spoke with three women who have been pioneers in the space.

Head here to read the full story.

Post link

On Episode 6, I was asked on my opinion on WAP and whether or not Cardi and Megan should be considered as role models to young children. What do you guys think? Should entertainers be held to the “role model” standard?

Episode 6: Listerine Things - Talkin’ With Tish

Episode 6 is available now!

Talkin With Tish Face Masks are available now for $14!! Let me know if you are interested in purchasing one!!! Purple writing available as well. (White Writing pictured above!)

On Episode 4, I give advice to a listener getting out a toxic situation with her ex

Available wherever you get podcasts!

On Episode 1, I spoke on the comparison between black on black violence & police brutality. Needless to say, there’s not a comparison

Episode 4: Self Love Is The Best Love - Talkin’ With Tish

Talkin’ With Tish is available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google, and wherever you get your podcasts!

Episode 3: I Love Y’all, For Real - Talkin’ With Tish

Talkin’ With Tish is available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google, and wherever you get your podcasts!

Episode 2: Personality Type - Talkin’ With Tish

Talkin’ With Tish is available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google, and wherever you get your podcasts!

Jemina-Ben For 2024 - Think Outside The Box!

Join Jemima Greenand Ben Rice (not related to Condoleeza Rice) in 2024.

Portraying Jemima was a little tricky, since the logos are difficult to work with. Candidate Jemima is based on the logos from the 50’s until the late 80’s, model Anna Short Harrington who promoted the brand until 1953, and blues singer Edith Wilson who became the first AJ to appear on TV and Radio. I kept her curves but no more head scarf.

Follow me on Instagram.

Post link

#BlackDisabledGirlMagic Series: Kerima Cevik, Disabled Writer, Activist, & Redefining the Rules

Photo of Kerima Cevik, a brown-skinned Black woman. Kerima is facing away from the camera, with her beautiful gray hair covering her face. She is leaning against window blinds, with the light from the window softly hitting her face.

It is so important for Black disabled women to have a village – a group of individuals who understand her fully. A group of uplifters, motivators, and truth sayers…

#BlackDisabledGirlMagic Series: Heather Watkins, Disabled Writer, Mom, & Community Leader

Image of Heather Watkins, light-skinned Black woman who is standing in front of a off-white colored door. Heather is smiling directly to the camera, and is wearing a black-and-white multi-striped top with black pants. Heather has her hands placed on her hips, which are in a relaxed pose.

As we continue with the #BlackDisabledGirlMagic series, we have seen the various perspectives about the lives…

Photo of Keri Gray, light-skinned Black women with a small afro who is smiling into the camera and throwing up the peace sign. Keri is dressed in business attire and is standing near a black podium. The podium has a white sign on the front of it that reads: “national youth transition center.”

For Women’s History Month, I want to spotlight the phenomenal Black women I know who are trailblazers and…

Black-ish & Speechless: The Night Primetime TV Got It Right

Despite the seemingly limitless TV programming options that exist for our entertainment pleasure, very few target the identities I have in a manner that are affirmative and validating. However, this month, two shows managed to meet this feat. Black-ishandSpeechlessaired episodes that touched on difficult topics that rarely are discussed as candidly as they should – race relations and…

Image of a group of protestors outside of a school building holding signs to show solidarity to the injustice committed to a disabled student.

The intersection of race and disability is often ignored when we discuss the injustices that disadvantage disabled students of color within our schools. This oversight can mean grave consequences to students who live within these margins. The…

During this period I had about despaired of the power of love in solving social problems. I thought the only way we could solve our problem of segregation was an armed revolt. I felt that the Christian ethic of love was confined to individual relationships. I could not see how it could work in social conflict.

Perhaps my faith in love was temporarily shaken by the philosophy of Nietzsche.

The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr.

“I was proud of my crime”

At the jail, an almost holiday atmosphere prevailed. People had rushed down to get arrested. No one had been frightened. No one had tried to evade arrest. Many Negroes had gone voluntarily to the sheriff’s office to see if their names were on the list, and were even disappointed when they were not.

-

Ordinarily, a person leaving a courtroom with a conviction behind him would wear a somber face. But I left with a smile. I knew that I was a convicted criminal, but I was proud of my crime. It was the crime of joining my people in a nonviolent protest against injustice. It was the crime of seeking to instill within my people a sense of dignity and self-respect. It was the crime of desiring for my people the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. It was above all the crime of seeking to convince my people that noncooperation with evil is just as much a moral duty as is cooperation with good.

The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr.

I took an active part in current social problems. I insisted that every church member become a registered voter and a member of the NAACP and organized within the church a social and political action committee—designed to keep the congregation intelligently informed on the social, political, and economic situations. The duties of the Social and Political Action Committee were, among others, to keep before the congregation the importance of the NAACP and the necessity of being registered voters, and—during state and national elections—to sponsor forums and mass meetings to discuss the major issues.

I joined the local branch of the NAACP and began to take an active interest in implementing its program in the community itself. By attending most of the monthly meetings I was brought face-to-face with some of the racial problems that plagued the community, especially those involving the courts.

Around the time that I started working with the NAACP, the Alabama Council on Human Relations also caught my attention. This interracial group was concerned with human relations in Alabama and employed educational methods to achieve its purpose. It sought to attain, through research and action, equal opportunity for all the people of Alabama. After working with the Council for a few months, I was elected to the office of vice-president. Although the Council never had a large membership, it played an important role. As the only truly interracial group in Montgomery, it served to keep the desperately needed channels of communication open between the races.

I was surprised to learn that many people found my dual interest in the NAACP and the Council inconsistent. Many Negroes felt that integration could come only through legislation and court action—the chief emphases of the NAACP. Many white people felt that integration could come only through education—the chief emphasis of the Council on Human Relations. How could one give his allegiance to two organizations whose approaches and methods seemed so diametrically opposed?

This question betrayed an assumption that there was only one approach to the solution of the race problem. On the contrary, I felt that both approaches were necessary. Through education we seek to change attitudes and internal feelings (prejudice, hate, etc.); through legislation and court orders we seek to regulate behavior. Anyone who starts out with the conviction that the road to racial justice is only one lane wide will inevitably create a traffic jam and make the journey infinitely longer.

The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr.

In Beirut’s Palm Beach Hotel, I luxuriated in my first long sleep since I had left America. Then, I went walking-fresh from weeks in the Holy Land: immediately my attention was struck by the mannerisms and attire of the Lebanese women. In the Holy Land, there had been the very modest, very feminine Arabian women-and there was this sudden contrast of the half-French, half-Arab Lebanese women who projected in their dress and street manners more liberty, more boldness. I saw clearly the obvious European influence upon the Lebanese culture. It showed me how any country’s moral strength, or its moral weakness, is quickly measurable by the street attire and attitude of its women-especially its young women. Wherever the spiritual values have been submerged, if not destroyed, by an emphasis upon the material things, invariably, the women reflect it. Witness the women, both young and old, in America-where scarcely any moral values are left. There seems in most countries to be either one extreme or the other. Truly a paradise could exist wherever material progress and spiritual values could be properly balanced.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X

The story is not complicated. Since that time in the hospital, I’d asked my uncle about it again and again. I was born when my parents were both twenty-six. Then when I was three, they got into a car accident coming back from a party. My dad was driving, and when they got a block away from home, my dad accidentally hit the accelerator instead of the brake and mowed into a lamppost before swerving the car and hitting the outside wall of a donut shop. It was nearly morning and the streets were empty, so nobody came when he screamed for help. So he stumbled home to get my uncle to help him get my mom out of the car. She won’t move, he kept saying. She won’t wake up! My uncle’s voice gets quiet when he tells that part of the story. My dad’s nose was broken and he had cuts on his hands and arms. My uncle was babysitting me. Before the three of us could get back to the car, the cops pulled up beside us and arrested my dad for leaving the scene of a crime. And for drunk driving.

He kept saying to me, my uncle told me, ‘Go get her. Please go make her wake up.’

My mother was six days away from her thirtieth birthday. But by the time the cops booked my father, my mother had been dead for hours. She will always be twenty-nine.

Harbor Me, Jacqueline Woodson

OSSIE DAVIS ON MALCOLM X

[Mr. Davis wrote the following in response to a magazine editor’s question: Why did you eulogize Malcolm X?] You are not the only person curious to know why I would eulogize a man like Malcolm X. Many who know and respect me have written letters. Of these letters I am proudest of those from a sixth-grade class of young white boys and girls who asked me to explain. I appreciate your giving me this chance to do so.

You may anticipate my defense somewhat by considering the following fact: no Negro has yet asked me that question. (My pastor in Grace Baptist Church where I teach Sunday School preached a sermon about Malcolm in which he called him a “giant in a sick world.”) Every one of the many letters I got from my own people lauded Malcolm as a man, and commended me for having spoken at his funeral.

At the same time-and this is important-most of them took special pains to disagree with much or all of what Malcolm said and what he stood for. That is, with one singing exception, they all, every last, black, glory-hugging one of them, knew that Malcolm-whatever else he was or was not_Malcolm was a man_!

White folks do not need anybody to remind them that they are men. We do! This was his one incontrovertible benefit to his people.

Protocol and common sense require that Negroes stand back and let the white man speak up for us, defend us, and lead us from behind the scene in our fight. This is the essence of Negro politics. But Malcolm said to hell with that! Get up off your knees and fight your own battles. That’s the way to win back your self-respect. That’s the way to make the white man respect you. And if he won’t let you live like a man, he certainly can’t keep you from dying like one!

Malcolm, as you can see, was refreshing excitement; he scared hell out of the rest of us, bred as we are to caution, to hypocrisy in the presence of white folks, to the smile that never fades. Malcolm knew that every white man in America profits directly or indirectly from his position vis-avis Negroes, profits from racism even though he does not practice it or believe in it.

He also knew that every Negro who did not challenge on the spot every instance of racism, overt or covert, committed against him and his people, who chose instead to swallow his spit and go on smiling, was an Uncle Tom and a traitor, without balls or guts, or any other commonly accepted aspects of manhood!

Now, we knew all these things as well as Malcolm did, but we also knew what happened to people who stick their necks out and say them. And if all the lies we tell ourselves by way of extenuation were put into print, it would constitute one of the great chapters in the history of man’s justifiable cowardice in the face of other men.

But Malcolm kept snatching our lies away. He kept shouting the painful truth we whites and blacks did not want to hear from all the housetops. And he wouldn’t stop for love nor money.

You can imagine what a howling, shocking nuisance this man was to both Negroes and whites. Once Malcolm fastened on you, you could not escape. He was one of the most fascinating and charming men I have ever met, and never hesitated to take his attractiveness and beat you to death with it. Yet his irritation, though painful to us, was most salutary. He would make you angry as hell, but he would also make you proud. It was impossible to remain defensive and apologetic about being a Negro in his presence.

He wouldn’t let you. And you always left his presence with the sneaky suspicion that maybe, after all, you _were_ a man!

But in explaining Malcolm, let me take care not to explain him away. He had been a criminal, an addict, a pimp, and a prisoner; a racist, and a hater, he had really believed the white man was a devil. But all this had changed. Two days before his death, in commenting to Gordon Parks about his past life he said: “That was a mad scene. The sickness and madness of those days! I’m glad to be free of them.”

And Malcolm was free. No one who knew him before and after his trip to Mecca could doubt that he had completely abandoned racism, separatism, and hatred. But he had not abandoned his shock-effect statements, his bristling agitation for immediate freedom in this country not only for blacks, but for everybody. And most of all, in the area of race relations, he still delighted in twisting the white man’s tail, and in making Uncle Toms, compromisers and accommodationists-I deliberately include myself-thoroughly ashamed of the urbane and smiling hypocrisy we practice merely to exist in a world whose values we both envy and despise.

But even had Malcolm not changed, he would still have been a relevant figure on the American scene, standing in relation as he does, to the “responsible” civil rights leaders, just about where John Brown stood in relation to the “responsible abolitionists in the fight against slavery. Almost all disagreed with Brown’s mad and fanatical tactics which led him foolishly to attack a Federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, to lose two sons there, and later to be hanged for treason.

Yet today the world, and especially the Negro people, proclaim Brown not a traitor, but a hero and a martyr in a noble cause So in future, I will not be surprised if men come to see that Malcolm X was, within his own limitations, and in his own inimitable style, also a martyr in that cause.

But there is much controversy still about this most controversial American, and I am content to wait for history to make the final decision.

But in personal judgment, there is no appeal from instinct. I knew the man personally, and however much I disagreed with him, I never doubted that Malcolm X, even when he was wrong, was always that rarest thing in the world among us Negroes: a true man. And if to protect my relations with the many good white folk who make it possible for me to earn a fairly good living in the entertainment industry, I was too chicken, too cautious, to admit that fact when he was alive, I thought at least that now when all the white folks are safe from him at last, I could be honest with myself enough to lift my hat for one final salute to that brave, black, ironic gallantry, which was his style and hallmark, that shocking _zing_ of fire-and-be-damned-to-you, so absolutely absent in every other Negro man I know, which brought him, too soon, to his death.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X

My hotel’s dining room, when I went to breakfast, was full of more of those whites-discussing Africa’s untapped wealth as though the African waiters had no ears. It nearly ruined my meal, thinking how in America they sicked police dogs on black people, and threw bombs in black churches, while blocking the doors of their white churches-and now, once again in the land where their forefathers had stolen blacks and thrown them into slavery, was that white man.

Right there at my Ghanaian breakfast table was where I made up my mind that as long as I was in Africa, every time I opened my mouth, I was going to make things hot for that white man, grinning through his teeth wanting to exploit Africa again-it had been her human wealth the last time, now he wanted Africa’s mineral wealth.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X

With less than fifteen minutes left, I began preparing an outline. In the midst of this, however, I faced a new and sobering dilemma: how could I make a speech that would be militant enough to keep my people aroused to positive action and yet moderate enough to keep this fervor within controllable and Christian bounds? I knew that many of the Negro people were victims of bitterness that could easily rise to flood proportions. What could I say to keep them courageous and prepared for positive action and yet devoid of hate and resentment? Could the militant and the moderate be combined in a single speech?

The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr.

But he looked to me, as I grew older, like pictures I had seen of African tribal chieftains: he really should have been naked, with war-paint on and barbaric mementos, standing among spears. He could be chilling in the pulpit and indescribably cruel in his personal life and he was certainly the most bitter man I have ever met; yet it must be said that there was something else in him, buried in him, which lent him his tremendous power and, even, a rather crushing charm. It had something to do with his blackness, I think—he was very black—with his blackness and his beauty, and with the fact that he knew that he was black but did not know that he was beautiful.

He claimed to be proud of his blackness but it had also been the cause of much humiliation and it had fixed bleak boundaries to his life. He was not a young man when we were growing up and he had already suffered many kinds of ruin; in his outrageously demanding and protective way he loved his children, who were black like him and menaced, like him; and all these things sometimes showed in his face when he tried, never to my knowledge with any success, to establish contact with any of us. When he took one of his children on his knee to play, the child always became fretful and began to cry; when he tried to help one of us with our homework the absolutely unabating tension which emanated from him caused our minds and our tongues to become paralyzed, so that he, scarcely knowing why, flew into a rage and the child, not knowing why, was punished. If it ever entered his head to bring a surprise home for his children, it was, almost unfailingly, the wrong surprise and even the big watermelons he often brought home on his back in the summertime led to the most appalling scenes. I do not remember, in all those years, that one of his children was ever glad to see him come home.

From what I was able to gather of his early life, it seemed that this inability to establish contact with other people had always marked him and had been one of the things which had driven him out of New Orleans. There was something in him, therefore, groping and tentative, which was never expressed and which was buried with him. One saw it most clearly when he was facing new people and hoping to impress them. But he never did, not for long. We went from church to smaller and more improbable church, he found himself in less and less demand as a minister, and by the time he died none of his friends had come to see him for a long time.

He had lived and died in an intolerable bitterness of spirit and it frightened me, as we drove him to the graveyard through those unquiet, ruined streets, to see how powerful and overflowing this bitterness could be and to realize that this bitterness now was mine.

Notes of a Native Son, James Baldwin, 1955

We came to see that, in the long run, it is more honorable to walk in dignity than ride in humiliation. So in a quiet dignified manner, we decided to substitute tired feet for tired souls, and walk the streets of Montgomery until the sagging walls of injustice had been crushed by the battering rams of surging justice.

When the opposition discovered that violence could not block the protest, they resorted to mass arrests. As early as January 9, a Montgomery attorney had called the attention of the press to an old state law against boycotts. On February 13 the Montgomery County Grand Jury was called to determine whether Negroes who were boycotting the buses were violating this law. After about a week of deliberations, the jury, composed of seventeen whites and one Negro, found the boycott illegal and indicted more than one hundred persons. My name, of course, was on the list.

The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr.

I want tell you the story of Perrito. He was my dog. He was part Doberman, part Labrador. He was the best dog. He was my best friend. He spoke Spanish and English. Sometimes, when Ms. Laverne asks us to write in class, it’s hard for me. The words don’t want to come. I see you guys all writing and writing and I want to do that too. But the words I write want to come out in Spanish, not English. And people are always saying, ‘Speak English! Speak English!’ Not you guys! When you see me and Esteban talking in Spanish, you just say, ‘Teach me.’ You don’t say mean things. Once when me and my mom were walking down the block speaking in Spanish, this guy yelled at us, ‘This is America! Speak English!’ But I’m from Puerto Rico, and Puerto Rico is part of the United States of America too, so Spanish should be American, right?

We all agreed. Amari was drawing but he kept nodding with the rest of us. Tiago’s quiet was beginning to make sense to us.

But me and my mom didn’t say anything, Tiago said. Because that guy was big and he looked mad. If Perrito had been with us, I bet that guy wouldn’t have said anything. Perrito was big too. And the Doberman part of him was mad protective of us. When me and my mom got to the next block, we started talking again, but my mom was whispering and I was sad that that guy with his red angry face made my mom quieter.

The four of you guys—he pointed to me, Ashton, Holly and Amari—you guys onlyspeak English, and I’m not saying there’s something wrong with that—

But, dude, Amari said, Puerto Rico’s a part of this country and you speak English too.

Yeah, I know, Tiago said. But I only speak in Spanish with my family. And in PR, even though we had to speak English and Spanish in school, I still liked speaking in Spanish better. His voice dropped and he looked down at his hands. And because I came from Puerto Rico, I’m safe. I don’t have to worry. Not for myself and my family. Just for my friends.

He stared at the voice recorder for a long time.

My mom, when she’s at home, she loves to sing in Spanish. She talks in Spanish. She cooks in Spanish. It feels like she even laughs in Spanish, because her smile gets so, so big. But when she goes outside now, she is very quiet, because she’s afraid another person like that guy will look inside her mouth and see Puerto Rico there. Not the beach or the sparkling blue ocean. Not the awesome pastelillos or the quenepas that are so sweet, you can’t stop eating them. She thinks they’ll see her small town of Isabela, where her dad raised chickens and on holidays her abuela made arroz the old way, on a fire outside, and everybody begged for the pegao—the crispy rice that stuck to the bottom of the pot. She thinks people here will say, ‘Go back to your country.’ Even though this is her country.

And it hurts her. It makes her sad and ashamed. Because if somebody keeps saying and saying something to you, you start believing it, you know. My mom has the past dreams of Puerto Rico and the future dream of this place. And this place acts like it doesn’t have any future dreams of us.

Harbor Me, Jacqueline Woodson

“In your land, how many black people think about it that South and Central and North America contain over _eighty million_ people of African descent?” he asked me.

“The world’s course will change the day the African-heritage peoples come together as brothers!”

I never had heard that kind of global black thinking from any black man in America.

From Lagos, Nigeria, I flew on to Accra, Ghana.

I think that nowhere is the black continent’s wealth and the natural beauty of its people richer than in Ghana, which is so proudly the very fountainhead of Pan-Africanism.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X