#historical film

Our focus on Black films continues with this week’s FFR episode on Julie Dash’s landmark 1991 release Daughters of the Dust, a daring film of remarkable beauty, rich with meaning and emotion, whose influence is still keenly felt today.

Listen on your favorite podcast app of choice.

NEW style of 18th Century stays in my store!

If you follow me, you’ve probably figured out that I’m a rebel. I don’t intentionally TRY to be salty, but with age truly comes wisdom and I’ve just reached a point in my life where I don’t seek the approval of others. The only approval I need is that of my clients who invest their hard-earned cash for a costume and it’s my job to offer them the highest quality I can.

Like many times in the past, real life situations inspire me to come on here and vent or just offer my perspective as a professional. I don’t claim to be “all knowing” or to have ingested every book publicized on historical clothing. I simply leave an open mind for further knowledge, and as such, I am constantly learning and improving because it’s hard-wired into my character to operate from a place of integrity.

The situation that stimulated THIS particular post happened this morning wherein I received a message in my Etsy store. It was completely innocuous, but it gave me an opportunity to remember why I have adopted the following philosophy. They actually used it in a scene in Outlander, but it’s an old Scottish witticism: “Bees with honey in their mouths, still have a sting in their tails.” Now, stick with me here because I have a salient point to make. Not everyone is going to agree with my opinions, and that’s fine with me. I march to the beat of my own drum and not everyone appreciates the tune.

I received a “question” via Etsy messenger in which she stated, “Fellow designer here. Wondering what documentation you have for the box-pleats on the doublet collar? Very unique.”

She was speaking about these particular doublets that I have made for clients and are listed in my store and on my website.

The following is my response, and in it lies the salient points I am attempting to make:

“Hello XXX,

Sadly, I’ve been the victim of some very “vicious” gatekeeping and censure on the part of other historical costumers, so I really am reluctant to enter any discussion of this nature. I hate how rude that sounds, and it’s not meant to be. I understand the limitations of writing rather than speaking and how it can lend itself to misinterpretation as the other party cannot judge my tone or intent.

I’ve had women, perfect strangers, come on my website, and here in my Etsy store over the past 10 years, solely for the purpose to tell me in no uncertain words that I had no “right” to call myself a historical costumer because “such-and-such” has no documentation, etc. Every single encounter has begun exactly as your question, then quickly dissolved into a situation wherein I’m being judged and criticized. You can understand, I hope, why this question leaves me reluctant to respond as I cannot judge whether such curiosity comes from a place of genuine interest, or if like all the other times it is a trap wherein I ultimately found myself the victim of bullying. :(

So, instead of offering specific documentation, I will simply beg your indulgence and ask you the following thought-provoking questions: What does it matter? Does every nuance a designer uses have to be based on a portrait, or wood etchings, etc.? I will say this much: all of my costumes are based on a historically accurate “cut” or pattern. I have an extensive library and I am constantly working to improve my craft. I use tailoring techniques on my doublets and men’s frock coats, and I try to guide my clients to fabrics that may “appear” more accurate, but there is no such thing in 2021 - with the exception of wool or linen. I have spent 20 years in research and bring that knowledge into my costuming.

I ask you with respect and absolutely zero shade: Why do we have to prove ourselves to strangers, or edit our creativity in fear of garnering the sanctions of those in the amateur costuming world who have set themselves up as the scions we must emulate, when none of them possess a degree? In truth, those who have felt justified in attacking me in the past are in essence simply homegrown hobbyists who, while following their passion, have adopted rigid, self-imposed rules in order to feel accepted by the “mean girls club.”

I have purposefully rejected that particular club. I don’t participate on any historical costume pages on Facebook because I don’t condone the snobbery and the vitriol, nor do I refuse to watch historically based films because the “costuming is inaccurate” like they do. Rather, I simply watch it because I am grateful and happy that such movies are made. I know that Hollywood is a business. They don’t make historical pieces for the passion, but for money. The more viewers these films have, results in MORE films of that nature being made. I understand that boycotting them for the inaccuracy of the costumes in reality just cuts off my nose to spite my face, so how is that a victory?

Please forgive the lengthy diatribe, this is my effort to empower you as an artist. I’m going to tell you what I wish all these self-righteous women would have offered me rather than scorn: If you love something, just enjoy it! If in your creativity you find yourself wanting to venture into something that is slightly more historically adjacent rather than something strictly reproduced from extant portraiture, just do it! In truth, NONE of our costumes are historically accurate. It’s impossible, unless we plan to weave our own fabric, dye it using extant mordants, and sew it completely by hand.

Be an individual, and express your passion likewise, and don’t concern yourself with having to document every single aspect of your work. Who cares if a ruff is box pleated or gathered. My only concern is producing pieces of the highest quality that look as if they walked off a filmset. If I love it, and my clients are happy, and I have more work than I can physically manage, then I have been successful. That’s my ultimate goal.

All the best!”

WHAT’S YOUR DOCUMENTATION:

That question may seem innocuous, but if you’ve ever been on the receiving end of the kind of bullying and vitriol I have, you will understand why it nettles me. Why do people participate in this damn debate? Is it that they see someone who’s enjoying a modicum of success and they are upset because they aren’t booked out a year in advance?

I spent about 20 years learning, living, and then teaching emotional intelligence. I’ve worked with many victims of abuse and with PTSD, and the concepts helped me to successfully parent two teenagers who grew to be wonderful adults, and to enjoy a successful and happy marriage of 27 years (before his untimely death in 2009).

Ask a psychologist, and they will tell you that the need to feel superior to others is a major cause of putting others down. Psychology says those who feel this need, bully in order to knock others down because by making another person feel small, the person who bullies feels bigger. They may feel superior in that they can assert their self-acclaimed superiority over another person. It could also make them feel strong or powerful to beat another person down. This need comes from a lack of stability regarding this person’s self-worth, and the bullying is simply a defense mechanism they have developed to shield themselves.

Unfortunately, the effects of this solution to feeling superior are short lived. The damage done to the person they bullied is much longer-lasting. Which is EXACTLY why I now grow suspicious when someone asks me to show my “documentation.” That’s totally MY stuff, but I just refuse to enter that debate.

Whether it’s the fact that I machine sew my costumes, or serge the edges of my pattern pieces, or take inspiration from “not-so-accurate” historical techniques, the bullying I’ve experienced is beyond the pale! However, the lesson here is that I don’t let it forestall my creativity. I keep pushing forward, experimenting, and improving where “I” judge I need to improve my work; and I am my own worst critic.

Simply put, I’m not going to defend myself when asked that question, which is why I kindly turned it around and instead of delving into offering “documentation” I offered thought provoking questions.

We have to STOP with the gatekeeping in this industry! I’m not the only one who has spoken out recently in that regard. It’s insidious! Outside of high school, I’ve never experienced the same kind of pettiness as I have since going public with my costuming.

I ask you: How does my use of box pleats, or a headdress that is historically adjacent, truly effect you personally? Examine your reasons for the censure of other costumers, especially those enjoying success. If you’re upset at the success of another, rather than become judgmental and pick apart the inaccuracies of their work maybe instead work to up YOUR game to produce the same quality of work. Maybe instead you can appreciate the meticulous craftmanship and seek to improve your own skills rather than point fingers and say, “That’s not historically accurate!” So what?! There are plenty of designers I’ve taken inspiration from whose work is NOT 100% historically accurate, and I have NEVER considered asking THEM for documentation!

Perhaps I “protest too much,’ but look, I approach my costuming with this thought: Could it have been possible during that era? Do the portraits we see of historical figures represent all that was possible in terms of embellishments or flourishes? The answer to that is NO. And even if it was a Yes, how am I hurting you by using box pleats, or serging the edges of my fabric or cut patterns to prevent fraying? How am I hurting YOU by machine sewing my costumes rather than hand sewing?

In the immortal words of Rodney King, “Can’t we all just get along?” Why do humans have to behave so hateful to each other? If you deem it justified to attack someone verbally, it CAN lead to the justification of other types of abuse, so just knock it off already!

I make it a habit to ENCOURAGE other costumers EVEN, or more especially, if their work isn’t on par with mine because I REMEMBER where I started, and I do not want anyone else to feel the way these woman have made ME feel. If you could see the stuff I made starting out! YIKES! But I kept working and improving, and practicing with one singular goal in mind: To produce clothing that looks as if it walked off the set of a film. Admittedly, that’s not always a good thing, but I’m speaking to the level of craftmanship rather than the level of accuracy.

It took me ten years to reach a place in my craft where I don’t feel the need to compete with my fellow costumers or defend elements of my work that veer into the realm of “historically adjacent.” There is a market for everyone’s work. I pay attention to my own business and seek to individually please each client who entrusts me with their money. I have not set myself up to be a ‘scion” in the industry, I leave that to The Tudor Tailor!

So, let us leave some space for individuality and just encourage and appreciate each other for our shared passion and leave a mark on the world for positivity. Can we do that?

In this century, when we think of “calico” we more than likely envision a cotton with a small print a la Little House on the Prairie, but calico in the 18th century was just a name for printed cottons and had nothing to do with a specific pattern or design.

It’s interesting to note just “how” printed fabrics were accomplished. A wood carver would create a wooden block of a pattern - such as a cluster of flowers, etc. That block or “stamp” would then be brushed with mordant to make the dye adhere to the fabric. The artisan would then stamp the design on the fabric, then dye the whole piece. It would then be rinsed to reveal the stamped design.

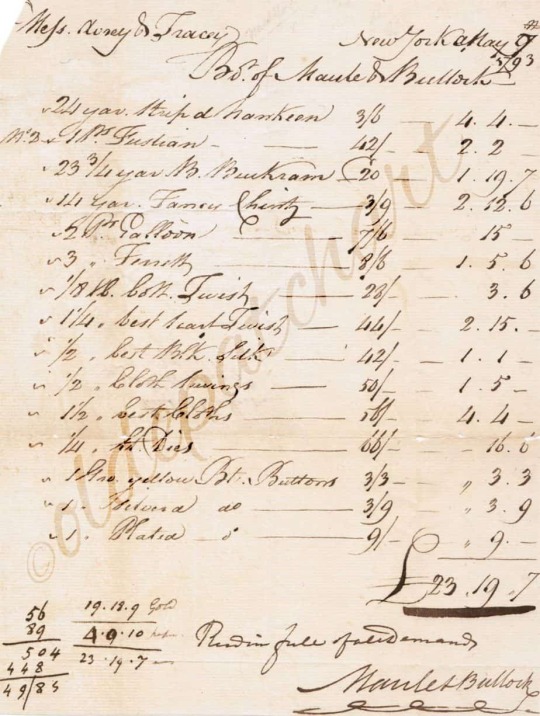

Attached is a copy of a bill of goods from New York dated 1793. I needed to know how much a yard of printed cotton would cost for one of my novels that is set in 1773. As a writer, research of such minutiae is par for the course, but as a costumer I was doubly curious.

“Chintz” was a type of printed cotton produced in India, The Calico Acts (1700, 1721) banned the import of most cotton textiles into England, followed by the restriction of sale of most cotton textiles. It was a form of economic protectionism, largely in response to India (particularly Bengal), which dominated world cotton textile markets at the time. Parliament began to see a decline in domestic textile sales, and an increase in imported textiles from places like China and India. Seeing the East India Company and their textile importation as a threat to domestic textile businesses, Parliament passed the Calico Acts as an attack on textile importation. This is the same reasoning Elizabeth-1 enacted sumptuary statutes on “black dyed woolen hats.” But I leave that topic for another time! The point being is that protecting English trade by banning certain imports was not a new device.

During the 18th century the monetary system in the colonies was in pounds shilling and pence. There were 20 Shillings to the pound and 12 Pence per Shilling. Also at the same time each colony had their own currency system. For instance the New York pound was worth 30% less than British sterling, with a NY shilling equivalent to only 8 pence sterling instead of the usual 12. Among the list of goods purchased on the 7th of May 1793 according to the bill of sale pictured, is a 14 x yards length of ‘Fancy Chintz’. It cost 3 shillings 9 pence per yard with the total cost coming to two pounds, twelve shillings and 6 pence.

Now, do not quote me as an expert. I’ve drawn my information from several on-line sources and it’s been suggested that these prices are very likely listed at wholesale, or purchased for “cost,” as the buyers themselves were merchants and would mark it up to make a profit.

Let’s consider wages in the time period of 1773 thereabouts. According to what I’ve been able to source on-line, the average wage for a farmer would be about 10 pounds per year. A day laborer, or farm hand, would make about 6 shillings per month. When you work out the comparison using wages of each era and try to calculate how much ONE yard of chintz would cost, it appears that it was equivalent to approximately three quarters of a day’s wage (in 1793).

Depending on the width of the fabric a typical round gown, which is a gown that isn’t split up the front and worn with a decorative petticoat, would take about 6 yards or more. I’m making that estimate based on what “I” would purchase for a textile that is 45" wide. That means the cost of ONE gown would equal to about a week’s wages! HOLY COW!

For us in 2021, cotton is an inexpensive textile. A polished cotton or chintz now days costs about $20 a yard. The brown and ivory fabric I used in the recent gown I shared cost about $19 a yard because it was a historical reproduction, but on average printed cottons cost about $10 a yard, while wool fetches a price of anywhere from $25 to $40 a yard! In the 18th century wool would have been much more affordable than cotton chintz or calico.

I’ve included some of my FAVORITE cotton prints that I’m anxious to have an opportunity to use on a robe a’ la polonaise! They are ALL available on Spoonflower. They are NOT historical reproductions, but… close enough to pass some prints from the 18th Century.

You can view my full “collection” of cotton prints on my Pinterest page:https://www.pinterest.com/…/cotton-prints-historical…/

A blog I used for reference: https://oldepatchart.com.au/…/11/18/yard-chintz-cost-1793/

Other sources were found on a Google search.