#jonathan swift

by Jonathan Swift

What’s it about?

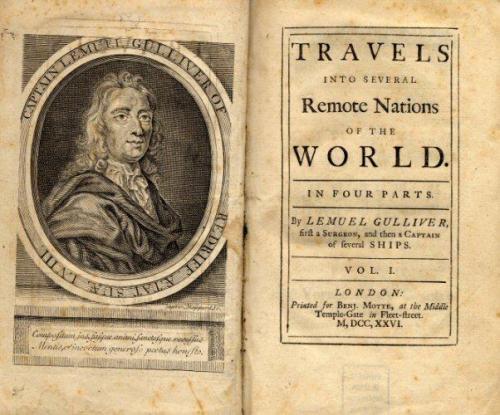

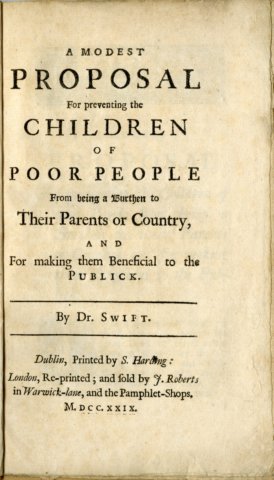

Printed three years before A Modest Proposal (a more obvious satire) Gulliver’s Travels can be read as a harmless children’s story. As with Animal Farm, however, in the hands of a politically-aware adult, it becomes something dangerous: an instrument of thought.

Yeah. That’s very clever. What’s it about?

It’s a record of travels to exotic lands. There are four parts to the book. By far the most well-known is the section dealing with the tiny people called Lilliputians, but there are other sections dealing with his travel to a land of giants, a land of wizards and scientists, and lastly to a land ruled by horses who consider their Yahoo subjects as ignorant peasants.

These Yahoos bear more than a passing resemblance to humans. A full understanding of Gulliver’s Travels would require a brief explanation of 18th-century English politics.

There is no way. No.

Don’t worry. The broad themes of greed, pride and inveterate political stupidity will be familiar to all. Although if you’ve read Game of Thrones and you’re put off by having to keep a bunch of political stuff in your head in order to understand the text, you should present yourself to the relevant authorities at first light.

What should I say to make people think I’ve read it?

“Political satire is always relevant.”

What should I avoid saying when trying to convince people I’ve read it?

Anything about the yahoo website.

Should I actually read it?

Yes. It’s a lot of fun and there’s a certain kick out of “getting” the sharper jokes.

“Most great writers suffer and have no idea how good they are. Most bad writers are very confident. Be willing to be a child and be the Lilliputian in the world of Gulliver, the bat girl in Yankee Stadium. That’s a more fruitful way to be.”

~ Mary Karr

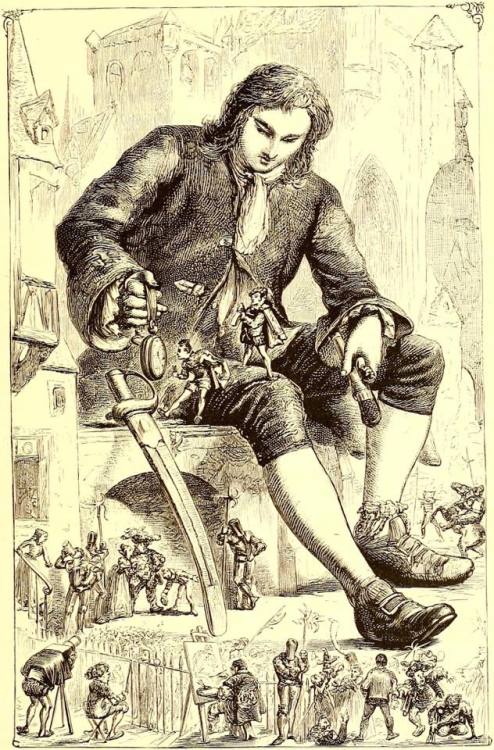

[“Lilliputians Examining the Man‐Mountain’s Possessions,” 1865 illustration by Thomas Morten]

• Karr’s work has received tremendous praise for its lyricism and beauty. Reviewing the breakthrough memoir, The Liars’ Club, in the New York Times, Michiko Kakutani noted that Karr’s “most powerful tool is her language, which she wields with the virtuosity of both a lyric poet and an earthy, down-home Texan. It’s a skill used… in the service of a wonderfully unsentimental vision that redeems the past even as it recaptures it on paper.” More: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/mary-karr

• Morten’s best work was unquestionably his monumental version of Gulliver Travels (1865). His illustrations for Swift are both well-drawn and sensitive to textual nuance. According to John F. Sena, these images are ‘extraordinary’ (p.118), especially in their representation of changes in Gulliver’s character as he is transformed from an imperial (and imperious) Englishman into a humble observer of life’s absurdities. Largely neglected, this book is an important work. More: https://victorianweb.org/art/illustration/morten/cooke.html

Post link

ATTENTION LADIES, GENTLEMEN, AND NON-BINARY BOOK NERDS THE WORLD OVER. I GIVE YOU…

…

…

THE 2018 OLIVE EDITIONS!

BuyFrankenstein by Mary Shelley HERE

BuyGreat Expectations by Charles Dickens HERE

BuyGulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift HERE

BuyJane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte HERE

BuyLittle Women by Louisa May Alcott HERE

BuyThe Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde HERE

BuyPride and Prejudice by Jane Austen HERE

BuyWuthering Heights by Emily Bronte HERE

To see past years’ limited edition Olive Editions, go HERE!

ECF journal for Spring 2016 (28.3) features a new article on Jonathan Swift, the master satirist:

“Dark Humour and Moral Sense Theory: Or, How Swift Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Evil,” by Shane Herron, Furman University

Read this article on Project MUSE: http://muse.jhu.edu/issue/33316

ReadA Modest Proposal by Swift online here:

https://andromeda.rutgers.edu/~jlynch/Texts/modest.html

For full-color portraits of Swift, visit the Getty online:

Post link

We get enough people at book fairs, sellers included, asking us what Speculative Fiction is that we thought an explanation was merited.

Note: I have no intention of arguing the case that science fiction and fantasy are as much skilled works of art as regular literature; that argument has been covered enough times and it bores me. Time determines what is art not genre.

As the term suggests speculative fiction is fiction that involves some element of speculation. Of course, one can argue that all fiction is speculative insofar as it speculates what could happen if various elements of a story were combined. Yet we feel that this term is descriptive enough to encompass the type of literature we want to categorise. First, a word about genre

Book genre is of limited use and is often more harmful than good. If you went into a bookshop and asked for literature, you’d be taken to the fiction section. If you said that you were looking for any Darwinian literature you’d be sent to the science section. At some point it was determined that literature suggested artistic merit. Yet we also use it to cover a particular grouping of written works. The point is that classifying the written word is a little futile as common usage will usually dictate what that classification envelops, and common usage is of course open to interpretation. Genre does however allow boundaries to be set for marketing purposes; if a reader enjoyed a number of books in a certain genre then there’s a reasonable chance they’d enjoy other books in the same genre. From a critical perspective, understanding genre helps align a work of literature with one’s expectations; certain tropes and mechanisms are, to some extent, more acceptable in one genre than another.

Now, this element of speculation. The speculation in speculative fiction isn’t concerned solely with speculation over how various story elements might interact, but speculation over the fabric of those elements. A work of speculative fiction takes one or more elements of an otherwise perfectly possible story and speculates as to what would happen if that element existed outside of current understanding or experience. Essentially, it’s writing about things that aren’t currently possible. The Road by Cormac McCarthy is a father-son story of survival, nearly everything is contemporaneously possible, except one thing the setting of the story is plausible future.

When you pick up an Agatha Christie, a Jane Austen or a Graham Greene, regardless of how the story unfurls, and how perhaps unlikely the story, it’s always within the realm of possibility (poor writing and deus ex machina aside). Yet a Philip K. Dick, a Tolkien or a Stephen King will always seem impossible, given current understanding.

The word current is key, to allow inclusion of scientific speculation. A seminal work like Kim Stanley Robinson’s Red Mars has a lot of the science in place to explain how the colonisation of Mars might / could take place (I assume the science is correct; it doesn’t matter to me personally but I know a lot of readers are particular in this area). The speculation is on how plausible, but currently theoretical, scientific and technological advances might solve a problem.

There is a slight grey area where such scientific knowledge and its technical implementation exists and is currently possible and a good story has been written about it. Imagine a book about travelling to the moon written in 1969. Imagine it’s not an adventure, it explores personal relationships between the characters and their heroic journey. For someone unfamiliar with planned space travel such a book would seem like science fiction, yet it was of course entirely possible in 1969. I personally wouldn’t classify such a work as speculative fiction as it doesn’t fit the definition, but I’d certainly class it as science fiction if I were to market it as it would fit the bill for many readers. Similarly a book like Psycho, it’s a work of horror but there’s no supernatural element and it’s plausible and possible given current understanding.

For books like The Hobbit orCarriethecurrent part of the definition becomes less important; Middle-Earth neither has nor probably will exist, neither will telekinesis. Of course, as science progresses some things that are currently implausible will be come plausible, if not possible. Space travel being a great example; progress is constantly being made.

Speculative fiction is also an umbrella term so includes the majority of works in the fantasy, science fiction and horror genres, also smaller genres such as magic realism, weird fiction and more classical genres such as mythology, fairy tales and folklore. Many people break speculative fiction into two categories though: fantasy and science fiction, the former being implausible the latter being plausible (in simplistic terms). This is helpful for those interested in having some sort of technical foundation upon which to build their speculation, and those who aren’t.

When one thinks of science fiction, one thinks back to the 1930’s and the Gernsback era, perhaps earlier to Wells and Verne. One might even cite Frankenstein. When one thinks of fantasy one thinks of Tolkien, perhaps Victorian / Edwardian ghost stories, Dracula, perhaps Frankenstein. It seems comfortable to think of these things as modern endeavours. Anything earlier often falls under the general category of literature (in the non-speculative fiction sense). Take More’s Utopia,you’d find that under literature or classics, not under fantasy. Similarly Gulliver’s Travels. Again, this is just marketing; there’s no reason why Gulliver’s Travels should not be shelved next to Lord of the Rings other than to meet a reader’s expectation.

At Hyraxia Books we like to think of certain classic works not simply as works that have contributed to the literary canon, but also as works that have contributed to the speculative fiction canon. For us, Aesop’s Fables,Paradise Lost, The Divine Comedy, Otranto, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Iliad, The Prose Edda, Beowulf and the Epic of Gilgamesh are not simply classics, but also speculative fiction classics. We don’t like to think of the genre starting in the last two hundred years, we like to think of literature (in the non-speculative fiction sense) having branched off from the speculative rather than the other way round. We like to see how that story has played out over the millennia.

That is how we define speculative fiction for the basis of our stock. Of course, we stock other items too, many of which we are very fond of.

There it is. We discussed this on “Shock Jocks.” One of the Tweet replies says, “I prefer the term ‘Tory Anarchism’”—a label self-applied, strangely, by George Orwell, a writer claimed by democrats, liberals, and conservatives everywhere. I’ve always liked it myself. Edward Said used it on Swift; I once transferred it to Yeats:

It is easy enough to say with Orwell that Yeats was a reactionary and a fascist. Edward Said, who did so much to redeem Yeats for the PC era by praising him in Culture and Imperialism as an anti-colonial poet meditating on Fanonian themes (in another mood, I might enter this into evidence for the fascist tendencies of identity politics), once wrote of “Swift’s Tory Anarchy.” The label might be applied to Yeats, who admired Swift: to his Tory elegy for a shattered culture of wholeness and authority, to his anarchic drive toward the shaping of a soul out of the chaos of experience.

Orwell, Said, Swift, Yeats. What connects the politics of these disparate men of disparate eras who between them cover almost the whole political compass? Consider the etymology of “Tory”:

mid 17th century: probably from Irish toraidhe ‘outlaw, highwayman’, from tóir ‘pursue’. The word was used of Irish peasants dispossessed by English settlers and living as robbers, and extended to other marauders especially in the Scottish Highlands. It was then adopted c.1679 as an abusive nickname for supporters of the Catholic James II.

The Tory is a reactionary because he is an outlaw of the progressive regime, the regime expropriating his country and trampling his culture with its forward march of progress. “Tory Anarchism,” then, is redundant. There is no real conflict between serving the exiled or prostrated old regime and wishing to bring down the new one, whether you are Irish or Palestinian or one of the British Empire’s inner critics.

But there is no going back—“retvrn” is the idlest of fantasies—so in theory the Tory’s anarchism should at length become less tactical or circumstantial and more of a substantive commitment to individual freedom in a new world, newer than the new regime which displaced the old one. He might still construe these freedoms as better defended by a unitary sovereign than by an oligarchy or bureaucracy, which is what, for this kind of sensibility, most regimes calling themselves democracies pragmatically are. But if the freedoms are the point—and the writings of Orwell and Said may bear this out in the end—then the distance between anarcho-monarchism and liberalism isn’t as far as their feuding partisans imagine.

Swift has sailed into his rest;

Savage indignation there

Cannot lacerate his breast.

Imitate him if you dare,

World-besotted traveller; he

Served human liberty.

—Yeats, “Swift’s Epitaph”

Post link

Instagram requests

angelica’s unusual laputa

i stumbled across a sweet edition of part three from jonathan swift’s 1726 Gulliver’s Travels, designed & illustrated by warren chappell: the angelica press edition of Gulliver’s Travels : A Voyage to Laputa [ nyc, 1976]. the book includes preface & afterword on swift, both by house proprietor dennis j. grastorf; in his introduction, grastorf describes chappell’s creation method for the illustrations—clever combination of letterpress, pen & ink, photography (1st illustration frontispiece & 2nd illustration): grastorf dubs this two-color chiaroscuro. i presume grastorf may also have been editor, & author of the colophon (3rd illustration).

perceiving the text set comfortably large i felt immediately attracted to a read; but was mystified to learn from the colophon that the text is set 12pt times new roman: upon analysis i make it 13/14, but it feels larger. admittedly, the 1970’s were the height of mini-computer driven film composition for offset litho: either the photo-typesetter manufacturer’s version of times was, somehow, large on the body or chappell’s 12pt specification was subjected to scaling by the compositor. in any event, i applaud the admixture of times & perpetua. i am, however, amazed that uppercase display is not letterspaced (aesthetically balanced)—absence of this in chappell’s work i have never noticed. perhaps the compositor had yet to unravel all the mysteries of his machine.

during the read i grew increasingly aware of anomalies of punctuation, first noticing quotation of statements, i.e. within inverted commas (e.g. 4th illustration); but these are reported statements, not direct speech—the editor not so daring as to recast the clauses. i also found colon & semicolon where simple comma is expected; checking several instances against a bona fide text my observations were confirmed: the editor embarked upon a bold new logic for punctuating swift, &, perhaps, overwhelmed by swift’s descriptions of the academicians of Lagado felt an urge to up his game, be more adventurous.

Post link

“A wise man should have money in his head, but not in his heart.”— Jonathan Swift (1667-1745) English poet.