#pakistan

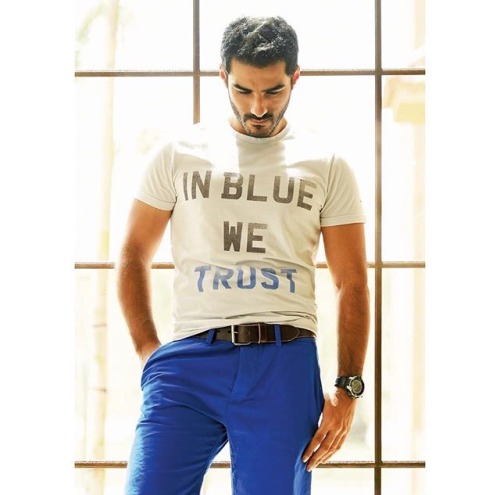

photo by Zeeshan Haider

text by yours truly

My journey officially begins at the Chitral police station, where Pakistani friends sip sweet green tea while Shane and I try to argue our way out of 24-hour armed escorts.

“I was here just last July, and I didn’t have a guard then,” says the adamant Irishman, a five-year resident of Islamabad and a seasoned traveller in the northern areas.

Apparently, since October 2010 — a point in time that seems completely arbitrary to us — all foreigners are assigned guards. Will the guards fit in our Landcruiser? Okay then, not a problem. They’ll send a separate truck. So the next afternoon, we begin the treacherous uphill chug into what was, until recently, the North West Frontier, following a pick-up packed with cops — at least seven at last count.

The midsized Kalash valley of Rumbur is the land that time — and electricity, mobile service and hot showers — forgot. It’s less commercialised than Bhumboret, the larger valley, and its population is almost purely Kalash — a tribe of Indo-Aryans who consider themselves the progeny of Alexander the Great. Rumbur has five villages of between 10 to 50 families each.

thepostmodernpottercompendium:

The Sacred Twenty Eight: The Noble and Most Ancient Houses of Shafiq and Shacklebolt (2/?)

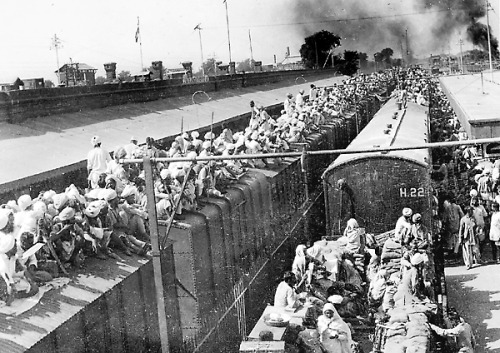

Pictures, left to right: Jallianwala Bagh Massacre 1919, Non Cooperation Movement 1920-21, Dandi Salt March 1930, Bengal Famine 1943, Trains during the Partition 1947, Indhira Gandhi visits Bangladeshi refugee camps in Bengal 1971.

He does not understand, when he is five, why his mother is weeping for people in a far away place with a strange name which is not home.

When he asks her, she only cries harder, and his father grips him roughly by his shoulder and pushes him away, admonishing him for troubling his mother. Someday, his father says, you will understand.

(He does not tell them, after asking his ayah, that he still does not understand why they care about wicked people who think they can get away with murdering innocent people. Why should they care? They are not theirpeople.)

He does not understand, two years later, when they return from the Halloween ball at the Ministry of Magic; the wrath of Kaliherself writ large upon his mother’s countenance (though she has long since given up her old family gods) and his father’s eyes shining with the same light of battle which must have once shone in their forefathers’ eyes as they swept out of the Hindu Khush following Muhammad of Gor.

Shafiqs are landowners and caretakers, yes, says his father, we grow and we create and we heal the land, but there is also anger in our hearts and when the time comes, we are warriors as well and all men quake when a Shafiq raises his arms to go to war.

(He tells his father he is not a Shafiq then, because there is no anger in his heart and his father only laughs and ruffles his hair and tells him that when he is older, the anger will burn in his heart too.

It is the last time, for a very long time, he hears his father laugh so openly.)

He does not understand, nearly twenty years later, why his mother both laughs and cries at the letter his father sends them from the old country, complaining about the damn bilatisthinking they’re clever by refusing to put us in prison. This is no laughing matter, being put in prison. It is wrongto break the law.

His mother silently hands him a book by a man called Olaudah Equiano and tells him that sometimes men make bad laws and it is for them, the ones who take care of their people, to fight those laws.

(He begins to understand, a few years later, when he realizes that his colleagues at the Ministry care more about Grindelwald’s war and its ill effects on England, not the millions starving back home, or the boats burning to keep the Germans (or the Japanese) from freeing his people; when they talk of oppression by mugglesand he wonders what the non magical folk have ever done to them that can be compared to what they have done to his people - then he understands, they do not look beyond their navels, so they exaggerate their pain, these pampered dandies.)

He does not understand why his father is grim-faced and his mother cries and cries and cries when Clement Attlee finally gives their countries Independence and the bilatisleave. It is a time for celebration - they have finally won their war. People die all the time. Let them die; they are not their own, they are mugglesthey do not have magic.

His mother goes into hysterics when he says this and his father fixes him with such a stare, he nearly wets himself.

Are you a Shafiq? His father asks him, are you my son or a son of a pig? A fool that you spew such nonsense? Are you blind? Have the bilatis turned your brain to porridge?

(He understands, a little, when as he watches his mother’s body burn on the funeral pyre, the tears begin to flow. Death is not easy to see. His father gruffly tells him to be a man and stalks away. Proud and tall as always.)

He begins to understand even more, when he meets his Anglo-Indian wife’s family and he listens to them drawling away about how the homeland is dirtyandstinky and his people are backward.They are your people, your forefathers he wants to yell, but smiles apologetically as his wife squeezes his hand sympathetically underneath the table.

He understands better, when he reads Macaulay’s Minute on Education (1835) and he reads these words:

We must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern; a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect.

He finally understands properly, twenty three years later, why his mother wept when their people, once united by common cause against their oppressors, turn on each other and commit genocide over divisions created by those very same oppressors they fought to drive away. He understands, when not a murmur is heard in the Ministry of help to be sent to them - when British newspapers are silent about sending troops to help clear up the mess they made in the first place.

But by then it is too late to teach his son what it means to be a Shafiq; to be rich and yet have anger burn in your heart.

So he teaches his grandson instead. These are only stories to them both, but he sees the fire of anger in his grandson’s eyes when he teaches him the history they do not teach them at Hogwarts. Of how the men of this country went to their homeland and stole from them in the greatest sanctioned robbery in the history of the world - 2.5 billion pounds (probably a lot more) stolen to never be returned. Of how, for two hundred years, they were taught that their ways were inferior and foolish, based on superstition not science. Of how they burnt their boats and stole the very souls and identities of people by turning them British, by turning them against their own culture (like your father, he says regretfully).

Of how these very men turned their people against each other: one religion against each other, countries arbitrarily divided along the lines of religion leading to one of the largest massacres in history. Of how ten million of their people were displaced overnight, in a war caused by the same arbitrary division of nations along the line of religion and politicking - this time for culture and language, because truly what did people in Dhaka have in common with people in Islamabad besides a vague commonality the bilatisdecided superceded all other commonalities? But now ten million people fit neither here nor there - they were not Bengali because they were muslims but they were not Pakistanis either (how could they be, those northeners were so different.) Ten million people with no identity, always to live unsure of themselves. This was the story of their people; magical or not, allof them were theirs.

And then many years later, his eyes are misty with tears as he watches his seventeen year old great grandson snap his wand and declare that he will not live as a bilatiwizard among a people with no conscience and no guilt for their cruelty. He goes to muggleuniversity instead, and then returns to his homeland to make a difference by working in a muggleNGO, practicing their old magic. The magic of their forefathers. And nobody serves him notice for using magic in the presence of muggles.

It is a start, he supposes, and then imagines his father would be proud. The anger has burnt in his heart and he has passed the flame of anger on. They will be caretakers, they will be warriors.

There will always be a Shafiq as long as they remember.

[Pic sources will be added later. Many thanks to notyourexrotic for helping with various bits of information and shaping this story (also for their incredible project shafiq28 which, I’ll be honest, shaped the headcanons for this one in a hugeway). I never liked the whole Statute of Secrecy biz given its ramifications when you apply them to other countries outside of the Euramerican region - its similarities with the whole divide and rule policy which governed Brit colonial policies when they were leaving countries are far too close for comfort.]

[[re-reblogging for this as there’s been an update to the original.]]

Post link

Many Pakistani and Bangladeshi Muslims deny their Hindu/Buddhist past prior to Islamic conquests and instead try to suck up to Arab Muslims assuming they are “brothers”. Meanwhile so many Arab Muslims, especially those in the Arabian Peninsula where the religion was created, not only have dozens of hateful derogatory terms for Pakistanis and Bangladeshis, but literally see them as subhuman and treat them like slaves in the Arab Gulf states.

Shiny, decorated and colorful water tankers park near a hydrant in Karachi, Pakistan. Diaa Hadid/NPR

In Korangi, a slum neighborhood of Karachi, a sprawling port city of some 16 million people in Pakistan, there’s no running water.

So how do people get the water they need to drink, to cook, to wash up and to clean their homes?

Residents have to call men like Mohammad Zubair, a driver who belongs to a group of water handlers known as the “water tanker mafia.” For a price, drivers will deliver clean water, which is pricey, or polluted water, which is cheaper.

A young man fills the jerry cans tied to his motorbike with water in the Korangi slum. Diaa Hadid/NPR

In a grubby café in Karachi, Saghir Ahmed, a water tanker driver, explains how the mafias work. He says that he and other drivers routinely pay off officials from Karachi’s water board, the police and the “landlords” — men who own the land where the government pipes are punctured, and who build valves to allow the drivers to pump the water. Those valves, used to steal government water, are called “illegal hydrants.”

“The water board, police and landlord — these three — they benefit, they take the money,” he says.

A large water tanker in the Orangi slum in Karachi transfers part of its water to a smaller tanker. The area doesn’t have running water, and the streets are too narrow for large water tankers, so residents move the water to smaller tankers that can ply the hilly area. Diaa Hadid/NPR

Read the full story here

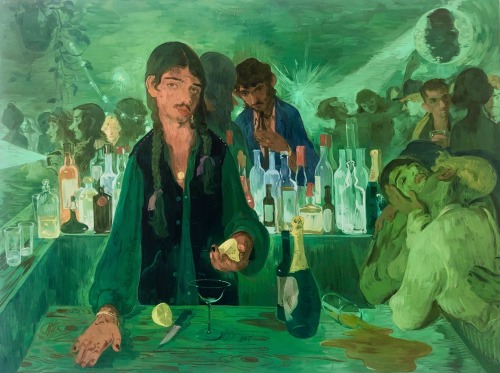

Salman Toor (Pakistani, b. 1983, Lahore, Pakistan, based Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY, USA) - The Bar on East 13th, 2019, Paintings: Oil on Panel

Post link

Last week, while reading news online I saw the headline “Pregnant woman, aged 23, stoned to death by own family outside of Lahore High Court”. To most it might sound like one of the million awful stories in the news each day – but for me it struck a nerve in a way that has only deepened since.

I’m one month into a three month engagement of working 4-days a week in Pakistan. The Lahore High Court is just about a mile away from where I stay – where I was comfortably sitting at the moment of the attack.

This proximity was my first thought. The insanity of something so physically near yet based on such incomprehensible logic or morals. Our existence was so close, maybe I’ve passed her on the street, we’re even the same age- but our experiences are opposite sides of a coin in a much realer sense than simply life and death.

For your understanding, the basic points of the story are as follows: The woman wanted to marry a man who she loved (and was pregnant by). Her family wanted her to marry a cousin and so went to the court saying she was kidnapped and raped – trying to get the male put in jail. The woman was on the way to the court with a declaration saying she was marrying the man out of her own free will. When she arrived at the court a cousin tried to shoot her, but missed. Then more than 20 relatives attacked her with bricks, crushing her skull.

After reading a few articles on the event, I spoke with some family and friends, here in Pakistan and abroad, about what happened. What I realized was how quick to disassociate people are, and how if I didn’t have the similarity of space, maybe I too would do so. The idea of “they acting like this" or “their problems" are so easy to consider, what’s more difficult is having this event make us think about the similarity to family quarrels, public violence, and female oppression in our own societies. Once we acknowledge that these issues exist everywhere, and give it a foundation that we too share- we can begin to explore the differences in extremity and maybe talk about solutions.

A large part of this disassociation is spurred on by the media- especially in regards to the illogical links to this event and Pakistan being a Muslim nation. Islam fully accepts “love” (self-arranged) marriages and clearly forbids forced marriages, and so shouldn’t play a part in this story. Why it is used, is to emphasize the difference, making it easier to see the attackers as unfamiliar outsiders.

But pushing beyond this attempt to help our disassociation, we can see the foundation of similarity and how the pulse behind this murder is part of something in every society: sexism and ownership. Why people find it acceptable to be unkind (whether saying bad things or killing) is because they value others less than they value themselves. Women most often get the brunt of this oppression because gender is a dichotomy that exists everywhere humanity does, and because it is an easily discernible difference. In family structures, sexism can take on the role of ownership and modern day slavery- i.e “The daughters’ only value is to the father, rather than to themselves”. When this value was taken away by the woman deciding herself who she wants to marry, the reaction was to devalue her through murder. When a parent sees a child’s value as “family reputation” and then the child comes out as homosexual, changes religion, or gets an awful piercing – often they are devalued by being disowned as a way of saying “you have devalued yourself and you do not exist to us or as a part of us”- a symbolic killing. Or, when a woman in America gets 70% of the salary of a male counterpart, she is being devalued as a contributing employee. It happens everywhere, very often to women, and through this extreme event we can reflect on how we skew value of others and maybe think about how we can fix that.

What sometimes makes this harder to accomplish, and did very much so in this case, is when a crowd or the public is involved. More than 20 people attacked the couple, and more than 30 (including police officers), were onlookers. Are we so afraid to hold different value systems than others in our own community that we don’t stand up for someone when they are being attacked?!

If your initial thought to the question above was that this would only happen “over there” then consider the viral video from a week or two ago that showed an actor passing out twice on a crowded Western street, once in a suit and another time dressed to look homeless. When he was in the suit, representing someone that is valued in society, everyone came to his rescue asking if he was okay. When he looked homeless, and unvalued, not a single person stopped to help.

It’s scary to think about standing up for someone, especially in a violent situation, but what’s scarier is when no efficient system is in place to ensure this happens. I’m referring to the on-looking police – which is where the focus of initial reform should be- in proper laws that protect citizens and a police force and judicial system dedicated to righting wrongs. We need to think about how we can make sure we equally value all persons and also make certain that our governments are doing so; governments should be the role models to their citizens.

Of course, for good story telling, one similarity is usually promoted- that of the victim. Which is why the headlines refers to her age, pregnancy, and the story to her “love marriage”. Promoting this familiarity is obviously good- but we need it on both sides so that we don’t just feel bad for the victim but so that we also work to understand our differences with the attackers. Because only when we deeply consider both, can we truly hope that it won’t happen to ourselves AND make sure we don’t do so to others.

It all sounds good, right? The idea of first finding shared foundations, then understanding the differences, and finally seeing how to bridge those differences to a shared respect for all humanity… but is it possible? How hard is it?

Why this event has caused me so many troubling thoughts is that it’s made me momentarily not so optimistic. I can write and talk on and on about the theories above because I’ve studied them closely and I’ve worked in many communities around the world to promote this in small ways- but can change be had with such an insanely low starting point, with a largely unwilling population, and deep societal acceptability (conscious or not) of hatred for others? Can it be done on a large scale? This situation of course being the same in my home country the USA as well as here in Pakistan and all over the world on various issues.

I ask because this is partly what I’m actually here to be doing, and even more so because it is what I’ve been trying to do the past 6+ years. This murder showed me how hard the battle ahead is – how deeply these (de)values are ingrained in people. Can we change anyone’s mind? Even just a little?

It is the last question that, through these moments of doubt, keeps me going. It is a fight worth pursuing, not one we’ll likely see the finish line of, but one that has rewards with each step. To stay motivated I just have to focus on those small rewards, and be guided by and push hard for the end-state but not expect it of anyone, including myself.

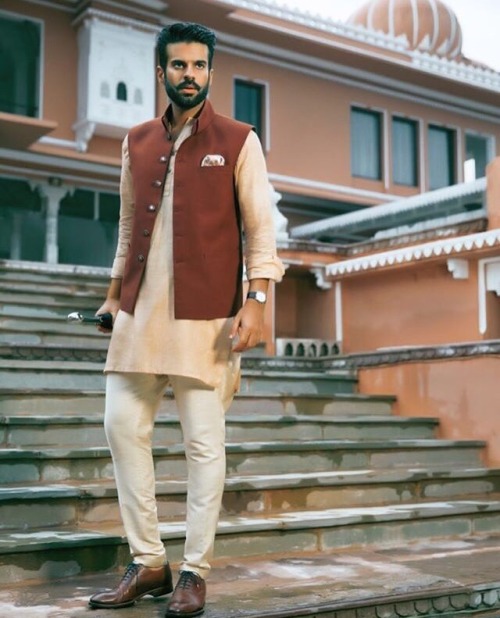

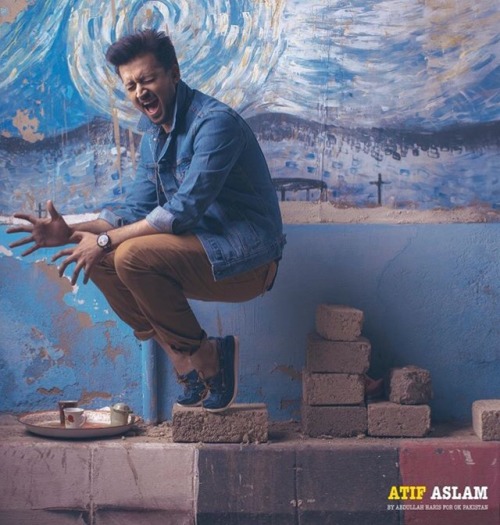

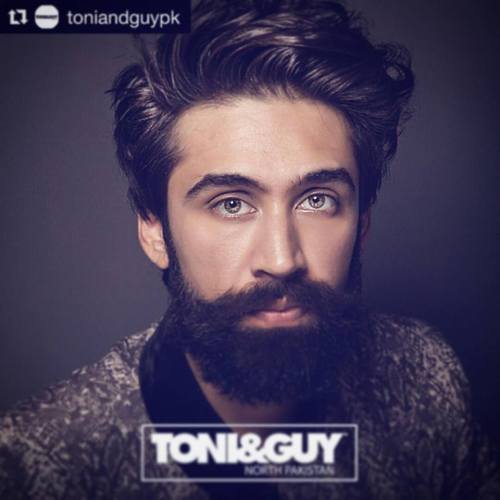

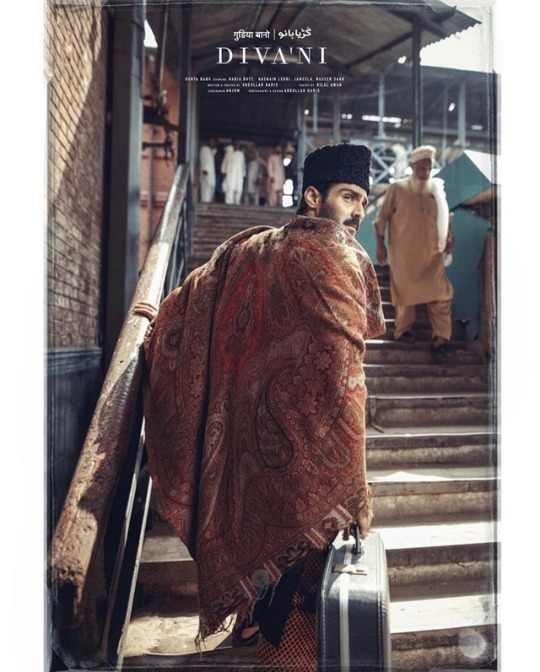

Hasnain Lehri

By Rizwan Haq

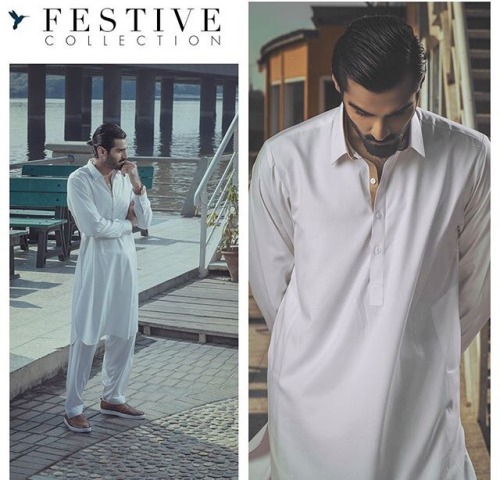

Hasnain Lehri.

By Abdullah Harris

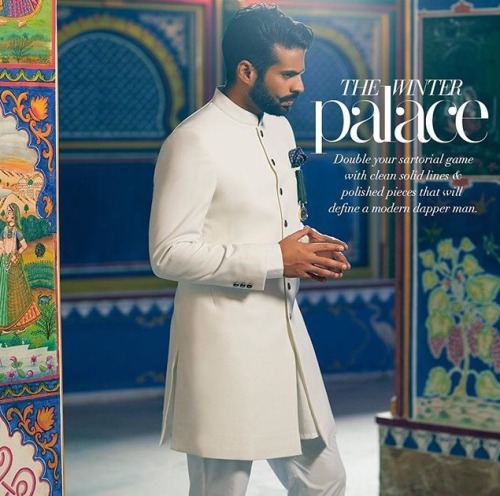

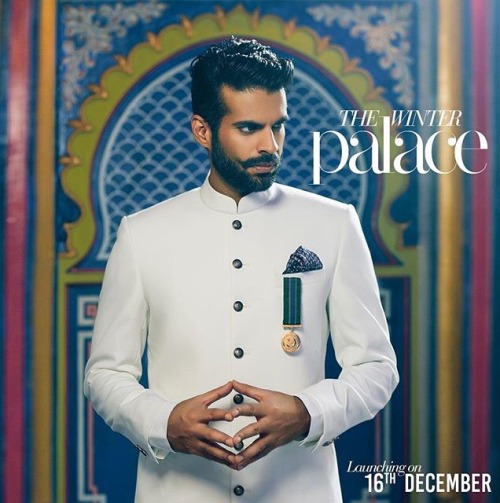

Aimal Khan for Republic by Omar Farooq

Shahzad Noor

My kind of BBW

Random Fact #3,605

The earliest known work on descriptive linguistics is also the most complex ever written, featuring a whopping 3,959 Sanskrit morphology rules.

The work, called the Ashtadhyayi, was written sometime around 500 BCE in the nation of Gandhara (now Pakistan) by a grammarian by the name of Pāṇini.

Indian national Geeta, right, who is deaf and mute, communicates with her colleague at charitable Edhi Foundation in Karachi, Pakistan, Thursday, Oct. 15, 2015. Geeta, who accidently crossed the border into Pakistan as a child nearly 12 years ago will return home soon, an Indian official said Thursday. (AP Photo/Fareed Khan)

Post link

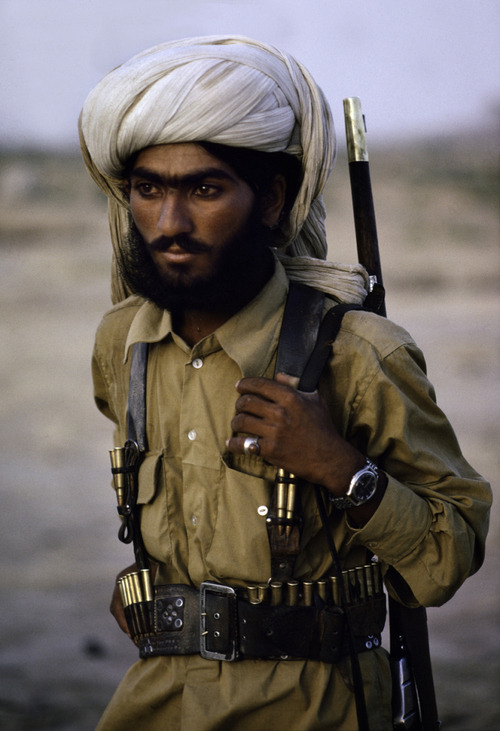

A member of the Pakistani security forces stands guard during the incineration of seized illegal drugs, in Karachi, Pakistan, Oct. 15, 2015. The Pakistani law enforcement agency burnt a large quantity of narcotics and alcohol seized in different parts of the country 15 October. (EPA/SHAHZAIB AKBER)

Post link