#sisters of mercy

ik photos of me don’t do well on this blog but oh well lol

Now offering limited prints at artbysweeve.bigcartel.com Each is signed and numbered 10"x14" prints Check it out

Post link

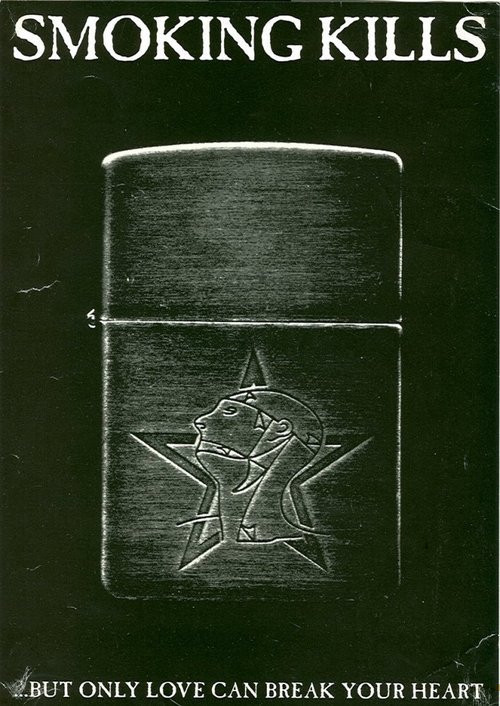

M’era Luna Nostalgia

This weekend was supposed to have been the M'era Luna festival, so as part of the festival’s online “Crypt Edition”, let’s have a drink and look back at M'era Lunas gone by

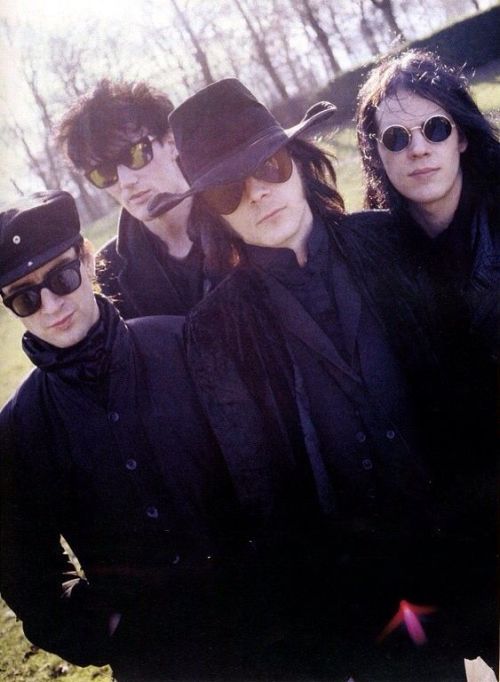

Gonna tell my kids this was sisters of mercy

Listening to The damned be like

have any of you read this book about extreme metal? i picked it up at a used book store a few months ago and i absolutely love it i highly recommend this book!!

It’s a Cat-Man-Bat! :D

Hairby@goamazons,ringsby@s-club-tbr,nailsandchokerby@pralinesims,jeansby@lazyeyelids,leather pantsby@darte77,crop topby@luumia,beltby@studio-k-creation,chocker #2by@kijiko-sims,bat wingsby@gerbithats, top #1by@oranos,skin and skin details by @soloriya, @ddarkstonee, @obscurus-sims,@luumia,@golyhawhaw and me:D! Aaaaand cat’s ears is something I’m working on!^^

Music’s playing:

Happy Halloween!^^

Post link

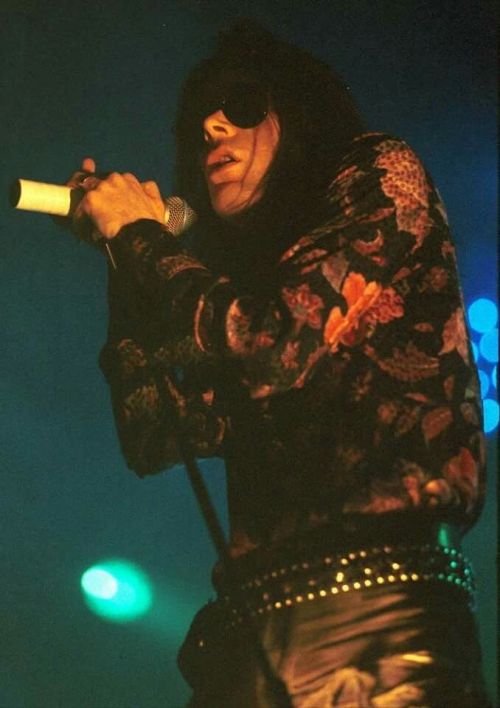

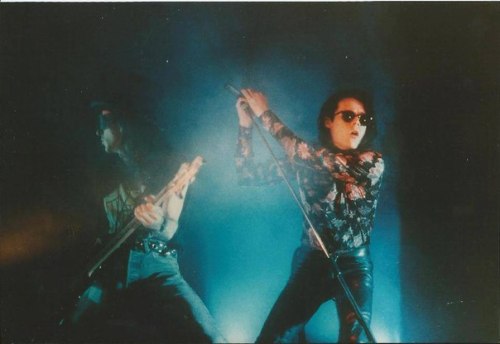

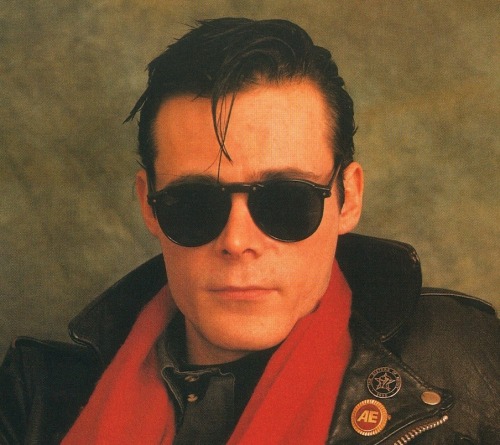

A rare MTV interview with Von Eldritch.

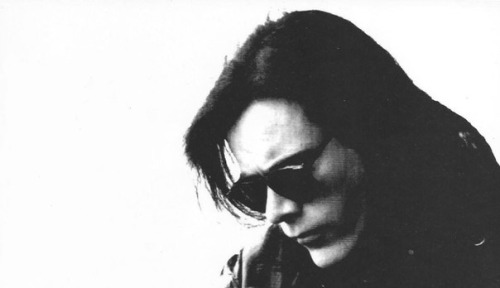

Who is Andrew Eldritch, you wonder, as you leaf through a pile of old interviews on the way to his current whereabouts in Bath. A character of the Old School, maybe, up to his eyes in Times crossword puzzles and Harvey’s Bristol Cream, whose first question to you would be a haughty: “So…what does your father do?” Or some gauche, neurotic Leeds University dropout who formed a band to overcome shyness, lack of height and inability to click with girls? A dashing, caddish rogue in a smoking jacket with the voice of a Shakespearian actor, dozens of puckish epigrams at his fingertips and a pack of hounds to set on you should your line of interrogation verge on the impertinent? Or a shy little geezer with a high-pitched southern twang, fingers that fidget manically with his Silk Cut and nervous eyes that dart around and do anything but look into yours?

Who is Andrew Eldritch?

He’d greeted us wearing shades, and once you’d got used to his small stature he looked just like the guy you see onstage: slicked-back hair, black coat, black leather trousers, motorcycle boots, a filter tip in his paw and a cruel slash of a mouth bidding a confident hello. Once we sat down in the pub and the drinks arrived, however, he took his shades off to do the interview. And away went the legend of Andrew Eldritch.

This is not the leader of the Sisters Of Mercy, surely, you think to yourself. Not this guy with his painfully shy eyes and his shaky fingers and his chirpy voice. This can’t be the guy who startled one interviewer by repeatedly swishing a fencing blade mere inches from his face while bemoaning falling attendances at county cricket matches. Bloody hell. This is the man who swaggers round Hamburg by night, smoke-screened in stealth as he moves from bar to bar. This is what Andrew Eldritch looks like with the shades off?

A Sisters Of Mercy compilation album comes out this month, entitled ‘Some Girls Wander By Mistake’. That’s a quote from the Leonard Cohen song 'Teachers’, which was the first thing the Sisters ever played live, on February 16, 1981. The album is a collection of early singles and EPs from 1980 to 1983. Eldritch is the first to admit that, in a few cases, this material doesn’t exactly constitute the absolute apex of Sororian wordplay, but press him on his reasons for dredging the old vinyl crypt thus, and he’ll merely flash some car keys at you and smile pleasantly. Ah, a Merc. Your first?

“I’ve never been able to afford a car before,” he nods, looking very proud. “I’ve never had that kind of money. No money at all for my personal enjoyment. So, er…” he rattles the keys, “this is why I’m putting it out.”

A classis model?

“No, no, a very sensible family saloon.”

Black, though, of course?

“No, white actually.”

Well, that’s no good, is it? Anyway, what’s it like listening to all this ancient history?

“It’s a tour de force of willpower,” he says. “It’s a tribute to persistence. It’s a good lesson to everybody who listens to that record, that if you try hard enough, no matter how bad you are when you start out, sooner or later you might not have to sign on anymore. I was signing on until '84, you know. The musical climate when all this stuff came out was totally against us. We were hated. We felt completely alienated from London and alienated from people who had money. Then, it was like Kid Creole was the be-all and end-all of everything. He was completely hideous. That’s what inspired us and a whole lot of people like us.”

There’s something odd about Eldritch’s speech. You’d have to hear it. It’s like something self-conscious. He doesn’t sound very confident at all. Maybe he’s still licking his wounds from last year’s aborted, loss-making Sisters/Public Enemy US tour. He’s trying too hard. When he makes a joke he goes “Erm!” at the end, just like Jimmy Tarbuck. His precise syntax evaporates if you press a point. He’s a likeable man, certainly, friendly and honest. But when he talks of coming off the dole as being of huge importance in the Sisters’ history, you can’t help thinking, Well, hang on, where’s the star-gazing in that? Where’s the cynical playmaster of other people’s emotions that you read about? Where’s the ruthless puppeteer, the smirking Don Quixote?

When he makes a couple of charming quips about his height (“when I was small…well, smaller”) it gets increasingly hard to square this Andrew Eldritch with the imperious Count Von Eldritch who bewitched 40,000 people at the Reading Festival last summer. He hasn’t, you know, sent along a stunt double today or something, has he?

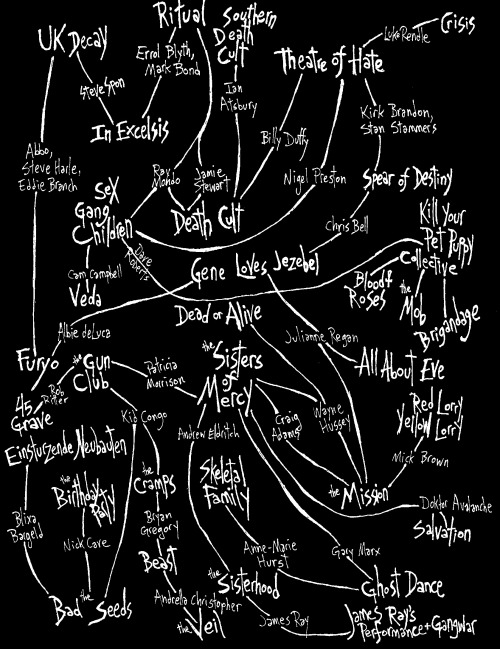

To best appreciate the embryonic Sisters Of Mercy, we have to Tardis our way back to the days of '80/'81, when sombre, commmitted bands like the Gang Of Four, Delta 5, the Mekons, and The Au Pairs sang of feminine armpit hair and Northern Ireland. Andrew Eldritch (or Andrew Taylor as he was then) was a shy Stooges freak studying Chinese at Leeds University. He and all his mates did loads of speed and not much else. On the first Sisters single, 'The Damage Done’ (1,000 copies only, 1980), Eldritch plays the drums and a little guitar. He was so crap at drums you can actually hear him drop the sticks at one point.

A year later the Sisters regrouped, and this time Eldritch was the singer. Now it was looking more like a band.

They were never quite like anyone else. They weren’t as arty as Bauhaus, nor as boisterous as Southern Death Cult. They didn’t have a drummer, just a cheap machine. They were pretty naff. One of their most famous songs, 'Temple Of Love’, was never played live because nobody in the band couple play the guitar part. The press in London tended to scoff. Eldritch is convinced some singles were reviewed on the strength of their titles alone. But, as any Peel listener from the time will tell you, the Sisters never seemed to go away.

A staple of a Sisters Of Mercy set became the well-chosen cover version. Their first gig ended with a 20-odd minute version of the Velvets’ 'Sister Ray’, with Eldritch frantically inventing additional lyrics. 'Some Girls Wander By Mistake’ has versions of the Stones’ 'Gimme Shelter’ and The Stooges’ '1969’. What does Eldritch think the Sisters brought to these classic songs, apart from the tinny sound of a drum machine?

“A bit more energy,” he says, and rattles on regardless of the loudly raised eyebrows. “You see, in those days we took a lot more drugs. I mean, we were really the bees’ knees when it came to amphetamine consumption. I’m sure we set quite a lot of records.”

Years of outrageous coyness on the subject of his drug intake have left Eldritch with a non-specific reputation of mysteriously derived illness the equivalent of, say, Dennis Hopper’s. Everyone knows he’s lived, but no one’s really too sure what he’s done. Just exactly how pharmaceutical are we talking about here?

“Well, I don’t want to get arrested, do I?” he says testily.

It’s eventually wheedled out of him that heroin was at no time on the shopping list; that cocaine changed his personality in all sorts of unsavoury ways and has been ditched with a vengeance; and that a few lines of cheapo whizz every so often are about his limits these days. And yet he insists that the Sisters “took up where the Stooges left off” and that the Detroit band’s “gonzoid rush” became in time a fully-fledged Sisters trademark.

The 1992 Sisters Of Mercy have two 'proper’ guitarists (Andreas Bruhn and Tim Bricheno), but still the same tacky drum machine they were using in 1980. They haven’t had decent bass player since Craig Adams left with Wayne Hussey to form The Mission in 1986.

And Andrew Eldritch is still no nearer to facing an audience without his trademark security blanket of smoke, 40W lighting smoke, dry ice, monumental echo smoke.

“I’m too terrified,” he says, looking like he means it. “I don’t like the idea of that at all. I think one of the reasons people like to watch me is because it’s obvious I don’t really have any technical ability, but there’s something about the way my terror manifests itself that seems to turn them on.”

You’re not cool at all, are you? You’re really human and frightened.

“Oh, yeah…I mean…yeah…” His eyes dart around.

So why is all this Transylvanian bollocks written about you in interviews and stuff? All this heroic Flashman nonsense. He exhales steadily. His answer is pretty weird.

“Because I have no social skills, no communication skills outside of my songs. And people are always a bit lairy of what they don’t understand. People don’t understand me because… (long pause) …because I don’t explain a lot of what I do, I just do it. I frighten people with my intensity…” His voice trails off. “I don’t like explaining. It’s futile.”

Did you kind of reinvent yourself as a rock start when you formed the Sisters?

“No,” he says quickly. “I’d already cut myself off from everybody before that. Really, I ended up in a band by default. I’d never picked up a musical instrument. I’d been banned from music classes at school since I was ten cos I couldn’t sing in key or play anything. I was completely incompetent. Tone deaf. I still am. Even today, if you listen, I’ve got a way of implying notes rather than singing them. And if it’s not in A, I can’t sing it anyway. The musicologists among you will notice how many of our songs are in A. It’s quite a lot. It is remarkable how much one can make of one’s limitations. That’s all I’ve done.”

As the Sisters records came out (all doing extremely well in the then-formative independent charts) Eldritch spent more and more time working on their lyrics. This became his domain. As soon as the conversation touches on his lyrics, all self-effacement and nervousness vanishes. Andrew Eldritch is adamant he’s simply the best there is. That’s better than Michael Stipe (“very good”), Lou Reed (“useless”) and, well, everyone else really… with the surprising exception of Richard Butler of the Psychedelic Furs, whom Eldritch rates as a true genius.

Wayne Hussey of The Mission does not rate very highly.

“Yes, well, there’s a difference between deliberately perverting language and not knowing what the fuck you’re doing,” says Eldritch briskly. “Wayne’s illiterate. My writing owes more to collage editing in film. It’s a richer use of language, that’s all. Plus,” he adds, quickly warming to his theme, “you need to be pretty clued up to get a lot of the humour in my writing. I write lines like : 'Stuck inside of Memphis in a mobile home’, erm! Now if you don’t know your Dylan (it’s a pun on a 1966 Dylan song called 'Stuck Inside Of Mobile With The Memphis Blues Again’ – Ed) you’re not gonna know that’s funny. There’s a lot of stuff like that. It’s like doing a particularly esoteric crossword. You not only have to know the Wordsworth quotes, but also who as the England cricket captain in 1965, or whatever. You have to have read a whole lot of Milton, Blake, Donne, Eliot.”

And here we are in another grey area. Eldritch refers several times to his “education”. He’s not from Leeds originally; he was born in the Fens in East Anglia (“so, of course, I hate the French, erm!”). A nomadic childhood peaked with an invitation to go to Oxford University to study German Literature, but the young Andrew Taylor couldn’t get a foothold in the class-conscious, punt-happy Oxford milieu and abandoned his course at the end of the first year. He went north, to Leeds University, to learn Chinese. Unnerved to learn that the plan was to dispatch him to Peking for a year of some intensive, closer-to-the-action tutelage, he dropped out and went on the dole. His Chinese is now, he admits, pretty shaky. He’s still to meet a Chinese person he can speak it to - the restaurants round his way are all run by Cantonese people who speak a different dialect.

But he considers himself “a linguist, a specialist”, and it’s this fascination with words and sentence construction that he brings to his lyric writing. He explains how he’ll omit the definite article here and there to get the listeners attention, or twist the grammar round so you get lines like “Acid on the floor so she walks on the ceiling” ('Body Electric’).

“I thought the 'Vision Thing’ album was unassailably brilliant,” he says. “I just love the language. I’m a linguist. Those little twists.” He inhales.

When most rock stars want a few hours of incognito relaxation away from the depredations of clammy hands of the superfans, they tend to whack the shades on. Andrew Eldritch takes his off.

“No one looks twice at me when I’ve got them off,” he says confidently. “Plus with this short haircut I look like a puny Marine. Ain’t nobody gonna recognize me now. When we do gigs I spend most of the time beforehand in the crowd, soaking it all up with the shadesoff.”

He goes into quite a passionate little speech about “being picked on” by strangers in public when he’s just trying to “live in my own space”. The Eldritch of cartoon legend, of course, would send these scurvy rapscallions on their way with a cuff round the ear and a piercing aphorism or two. The real Eldritch just says: “Nah, mate. Sorry. You’ve got the wrong bloke.”

How do you feel about your fans? Are you protective of them?

“Oh yeah. I hate it when they get slagged off. The worst kind of reviews are when they say, Well, it’s a pretty good record but who wants to be associated with the other people who are going to buy it? As if they’re obviously morons. That really upsets me.”

Do you get the feeling your music helps them through something?

“Yeah, I do. I get letters along those lines. I do know there are a lot of people who find sustenance there. We’re just trying to provide a soundtrack for people with the same worldview as we have, whatever that might be. I think our music has values, and I don’t think that’s anything to be ashamed of at all.”

Would your fans be disappointed if they met you off-duty?

“No, I think they’d be pleasantly surprised, because I do give people the benefit of the doubt. People keep having a go at me, you know. People take advantage of me quite a lot. It’s because I’m actually quite easy-going.”

His eye contact’s all over the place now. What’s this all about?

“No, I think the only reason they’d be disappointed is because I’m obviously shorter than they think I am. I’m five foot nine, and I’m not pretty. I know I’m not pretty because before I was in a band I was completely unattractive.” He looks down at the carpet. “I like…I like those little twists of language, you know, I…I don’t like people to be paying attention to what the hips are doing. I just want them to…get the most out of the songs…”

A sudden, almost sympathetic thought occurs. Would you be happier with your shades on?

“Yeah, I would,” he exhales. “I mean…it’s occurred to me, yeah. I just thought it might make things difficult for you.”

Don’t you think the Sisters fans would respect you even more if they knew you were this human? He finally snaps. He’s had enough.

“Look, it’s not up to me to tell them, is it? Why should they believe anything I say? One of the things I’ve always said to them is, Look, I know I’m telling the truth, but what I do is akin to being a rock 'n’ roll star, so you’d want to be very careful before you believe anything I say. Now why should they believe me? Eh? If anyone’s gonna tell 'em, you tell 'em. I write songs…”

With little twists. Sure. Next time you’re at a Sisters Of Mercy gig, take a good look around the crowd beforehand. Look for a little guy in a leather jacket with a cruel mouth but incredibly nervous eyes. Ask him if he’s Andrew. The chances are he’ll say no and scuttle off through the crowd, head down.

And when the lights go down and all that bloody smoke billows up and that imperious looking figure with the matchstick legs and the voice of doom salutes the first delerious cheers of recognition, ask yourself this: who is Andrew Eldritch?

Interview is taken from: Halluciente’s The Sisters Of Mercy Website - Interviews

A monstrous 30-minute interview, transcribed by me. The audio is very poor so some parts that I couldn’t make out are missing. From a limited edition interview disc. Andrew discusses the recording process behind Floodland, studying at Oxford University, and the origins of the band, among other things… Enjoy!

INTERVIEWER (I): You said you didn’t like London.

AE: It’s horrible.

I: So where are you based now?

AE: …In London. All of the interviews have to be done in London.

I: No, I mean where do you live? That’s what I mean.

AE: Patricia lives in London.

I: And you?

AE: I live in Hamburg. And Leeds. It’s sort of, um, moving between the places. Nothing really settled, no. I mean, Patricia has a permanent place here, I have a permanent place in Hamburg, I have a permanent place in Leeds. We do have a permanent office in London, but we’re never in it. So we get together here, sometimes there, sometimes… It’s nice that way. It’s nice not to have a… I remember in the old band there was one rehearsal room and there was nowhere else to go. Now there’s different countries to go to. Much healthier.

I: But now there’s no band to rehearse it! Now, uh, do you find London exciting because you’re from the other side of the pond?

PM: I travel too much to find London exciting. Yeah, I’ve been here three years.

I: So you’re based here for the convenience or what?

PM: Yeah, working. Beats commuting through Los Angeles. I have no particular love for Los Angeles, not enough to stay there. What I wanted to do was move.

I: So let’s get to the main topic. The album. How does the–

AE: Have you heard it?

I: Yes.

AE: Do you like it?

I: Yeah.

AE: Really?

I: Especially the first track. It intrigues me very much. “Mother Russia.”

AE: I think it’s going to be the next single.

I: Mhm.

AE: (pause) You really like it?

I: I do really like it.

(Patricia and the interviewer erupt into laughter)

PM: Do you not believe him?

I: Yeah, yeah, I see that he doesn’t believe me! Yeah, I love it!

AE: Yeah, well, I’m still just making sure… Sorry.

I: That is an artist, doubting in his abilities and hoping that it could have been improved if there was enough time.

AE: That’s certainly part of it, yes.

I: It’s a great album, really. I’m not trying to be nice because I’m talking to you, I really mean it. My favourite - if there was a favourite track - 1959.

AE: Mine too. Now that, that I think is finished. Yes.

I: I find Mother Russia a really great track as well. I don’t want to belittle the other tracks but that one jumps on you.

AE: Yeah. That does sound very… Um… I think it’s the only song on the record that really grabs the listener by the throat. Cause it’s very… All the others say, “Okay, we’re gonna - we’re songs, we sit here, we do what we do. If you don’t wanna listen that’s okay.” But Dominion says “Right, listen to this.” Which is a good thing once in a while.

I: So why didn’t you put it out as the first single?

AE: Because it wasn’t stupid enough. (Laughs) No, we hadn’t put out a record in a very long time and it seemed like a good idea to make the first one totally outrageous. Totally over the top. I think it’s ferocious, suitably. Over the top.

I: Were you expecting it to be a success?

AE: I think we’re pretty successful. (??)

I: So there was an element of surprise in it, after all.

AE: Yeah, we weren’t expecting it might do well in the charts.

I: That’s what I meant, chart wise. Not-

AE: Yeah. That was a bit of a… The week before it came out they said it’s gonna go straight in at number four. Which is sort of strange because none of the previous records went to the top forty. So from not going into the top forty at all to going straight in at number four is… It makes the difference.

I: Do you think that absence makes it more worthwhile to an audience?

AE: Yeah.

I: You became sort of precious, in a sense. Like they only had whatever it was to play at the time.

AE: Yeah. And that’s what I’m worried about now. Because I’m worried that expectations are higher than any record could deliver.

I: I don’t think so. I think that the album rises to any expectation.

AE: It’s not as good as the next one. I promise.

I: Well I’ll be contented with this one for a while. I tell you.

AE: Good.

I: Tell me about the writing process, I mean obviously having a listen to the listening cassette on me (?) have no credits of any kind. Is it all done by you or do you work together or…?

AE: Well, I tend to do the writing and Patricia tells me which are the bad bits… Which are the good bits.

I: Is she brutally honest?

AE: No, she doesn’t tell me where - at the moment, she doesn’t, um… Tell me enough about the bad bits.

I: So you have to figure them out yourself.

PM: What?

(Laughter)

PM: I tell him about the bad bits, but-

AE: Not when I’m writing it, you don’t.

PM: Yeah, I wait a bit too long.

AE: Yeah…

PM: ‘Cause I don’t know if I don’t like it yet until I realise that’s it, 'cause things change so much when it’s being done… And it’s not what I expected… Or gone past what it should have been.

AE: Yeah… Yeah, when it comes to production she certainly tells me which are the bad bits.

I: How about your ego? How does it take it?

(Pause)

I: I mean it surely-

AE: Yeah, I think it takes it okay. It wouldn’t take it for anybody else but it takes it for Patricia.

I: Not because, you know, it’s usually said that songs are sort of children. Artist’s children. So when someone says it’s no good it’s like telling a parent your child is rubbish or something.

AE: Yeah, I accept the fact that every now and then you can bring out a bad one. So…

PM: Sometimes you’re too close to see it. So that’s where I come in.

I: It’s been a long, long time since you had a record out. So how many songs did you have to choose from? Was it a big selection?

AE: No. About fourteen.

I: I presume from everything you’ve written you narrowed it down to fourteen. And then some more.

AE: …Yeah…Yeah.

I: How much did the music change from the downstage(??) to what it became?

AE: We only did a song and a half. And that didn’t really change at all because we didn’t add any extra parts. We just made sure it all got put on to tape.

I: Mhm. So what did you pay in monies? Was it very expensive?

AE: It’s - because it’s a big project, making sure it all got put down right. And unless you’ve got a producer with a very big name, the record companies are very disinclined to pay for things like quiet.

I: Mhm.

AE: It’s sad.

I: So who’s the producer?

AE: Originally it was being done by Andy Hill. But we fired him. So we did it.

I: And you did a great job of it! And did you produce the original as well?

AE: No, I didn’t produce the first Sisters album. But I did all the singles.

I: So being back in Hamburg, do you find it very stimulating for writing?

AE: It is for me, yeah. I get to meet a lot more people in Hamburg than I would if I lived here. (Pause) I just find that Hamburg is a town - a nice continental town. So it’s generally laid out better. To give a boy what a boy needs.

I: I see. Good for socializing with musicians?

AE: No, not really. In fact there aren’t that many in Hamburg. Which is nice. Musicians are very boring. People in bands, when they get together and talk about things, it’s very, very boring.

I: (Unintelligible)

AE: All about touring…

I: Slashing(??) about the record company…

AE: Yeah. It’s like, creepy sometimes… Very very devious…

I: Are there many groupies in your touring career? (Chuckles) Maybe I

shouldn’t have asked that.

AE: …I…

I: You have a certain status at a time. I don’t mean personally but what are girls saying about the band?

AE: Yeah…

I: Is it complimentary or worrying, in fact?

AE: It depends on how one reacts to it. To start with it was great, then - then when you start taking for granted… When you start assessing the audience by how many people you think you’re going to sleep with afterwards, then you think maybe it’s doing something bad to you. So it’s time to stop.

I: And not succumb to it. (??)

AE: And won’t go anywhere with them. Off-stage, to start.

I: Um, the last gig you played was in 1985. Now, I’m trying to remember something myself I couldn’t find out. Was there a Sisterhood at the time?

AE: No, that came afterwards. That came after the Sisters split up.

I: That’s right, yes. That I’m particularly interested in.

AE: Right… Wayne and Craig decided they wanted to be The Sisterhood. I thought it was a very bad idea. Um, I stopped them using the name The Sisters of Mercy. I stopped them using the name The Sisters. Then my lawyer told me if they wanted to be called The Sisterhood, there was nothing I could do about it. So I thought, well, there is. Just do it before they do. Hence the record. And hence the fact that they then had to change their name.

I: Moving on to the next question is, wanted to know the history of the band. It is your band. I mean you got the band together?

AE: Well… No, I was only really half responsible because the original guitar player was also half responsible. The guy is now in Ghost Dance.

I: But in any case, Wayne didn’t have much claim.

AE: No, not at all. But in English law, the Sisterhood is far enough away from the Sisters of Mercy or the Sisters to get away with it. If I hadn’t done anything.

I: So I assume you parted with animosity.

AE: We parted very amicably, but then we agreed that they weren’t gonna use the name The Sisters of Mercy. And I only found out by accident that’s what they were trying to do. And that’s when it got serious.

I: You went to Oxford University, correct. And when you decided to morph into making music, how did your parents react? Did they support you, or say it’s not a career, you’re going to throw it away?

AE: I have no idea. After Oxford I moved to Leeds. Um, and it was there I started getting involved in music. And by that time I’d long since stopped having anything to do with my parents.

I: Why Leeds? I mean it’s not really any place for-

AE: There’s only six places in Great Britain where you can learn Chinese at university, and Leeds is one of them. And that’s why I went to Leeds. When I was at Oxford I was doing French and German and they wouldn’t let me change to Chinese. So I left. And I went to Leeds.

I: The course, have you ever finished it?

AE: No, 'cause now I’ve got-

I: To do more with music?

AE: Yeah.

I: Do you still do some research or study on it?

AE: No, I haven’t the time for it. No, you really need help to do something like that.

I: Too many characters or?

AE: Yeah. I’m not quite articulate. And I was learning Mandarin Chinese, which is mainland Chinese. And you need help to learn that, because everybody here - all the Chinese immigrants here speak Cantonese, which is very, very different. So it’s not like I can walk in to Soho and expect to get someone to teach me how to speak Mandarin Chinese. Another reason I left is because they were going to send me to Peking for a year, as part of the course. And Peking is only sixteen square miles, and for a year you’re not allowed out of it.

I: Really?

AE: Mmhm. And I didn’t think it was a very good idea. I tried to get them to send me to Taiwan, which is a fun place. But… no. They made an arrangement with the Peking government. All the students had to go to Peking for a year. It gets to like thirty degrees below zero in the winter. I didn’t really fancy that.

I: But would you be tempted to go as a tourist?

AE: No. There’s not much to see. Go out to see a tractor farmer. Some murals. That’s about it.

I: So when did you two get together?

AE: We were touring together, when Patricia was in The Gun Club.

I: Did you spot them or the other way around?

AE: Other way around. They should have been spotting us.

I: I see.

AE: This was a very long time ago. And we just stayed friends. About five years now.

I: And did you physically get together often?

AE: About two years ago.

I: That’s been a very long time to go without-

AE: Well, we spent a while doing other things. There was a lot of legal stuff to go through with the record company. That took about a year. And I was very unhealthy. It took a year to get healthy… Too much touring.

I: And that’s why you won’t do it?

AE: Yeah.

I: Do you ever consider your fans?

AE: Yeah! But they wouldn’t let me kill myself on their behalf, I’m sure.

I: But would you do a one-off show or…

AE: That’s certainly being considered, yeah. A special something.

I: Not twenty-eight gigs in thirty days or whatever.

AE: That really would kill us.

I: Mm, I’m sure. So is there a pool of musicians here you can use?

AE: Right now, no, there isn’t. We don’t have very many friends that are musicians. We don’t get on with them very well. (Laughs)

I: Do they consider you to be a difficult person to deal with?

AE: Yeah.

I: Is he?

PM: Well-

I: When you get to know him, I mean.

PM: He’s very detailed.

I: Would you say that there is a front? You know, to protect himself from bad influences, like other music?

PM: Yeah.

I: The other alternative is that he’s too honest. People don’t like that. I see.

AE: I just have no respect for people who complain to me, that’s the problem.

I: So how do you see the function of music? Not your own music, but music in general. What musicians do.

AE: The problem I have with it is that it should do everything at once. You should be able to create a song which is capable of doing everything at once. And most people seem content to create something which can do one thing, or another, or another. And if you try to get them to make it a more complicated, more complete machine, that’s hard work. Not just anyone can do that. If you sit down with someone and say, “Okay, we have a song. How can we make it better?” They say, “Well, it’s okay as it is.” I say, “How can we make it better?” And they say, “Well, we don’t want to make it better. We just wanna go out and tour it now.” I have a real problem with that. I say that you have to make it the best it can be first. And most people find that very boring.

I: So that’s a communication break-up.

AE: Yeah.

I: What about the last album you enjoyed?

AE: …The last new record?

I: Yeah.

AE: I think the last Iggy Pop album. I thought that was very good.

I: You don’t think it sounds like a sellout?

AE: Yeah.

(Laughter)

AE: That’s probably why it’s a very good record. It didn’t worry me if that was the case. I thought the songs were great.

I: I enjoyed the album but it was too into (??)

AE: I thought it was far better than David Bowie’s record. It’s been a long time since David Bowie made a record that was that good.

I: What were you like growing up? Were you very interested in music at an impressionable age?

AE: Yeah, I seem to be able to remember a lot of it, so I suppose I must have been. But I never thought I’d be doing it. I never had any musical talent at all. I was banned from music classes - thought I would never ever be able to understand anything. And I believed that. I thought that was perfectly true. I’m quite perplexed by that.

I: Never thought you’d be a lead singer or whatever?

AE: Oh yeah, I can play the recorder.

I: That’s a great instrument. Come on.

AE: Well, no, in this country if you can’t play the recorder, that’s it. That’s your musical career, finished.

I: Tone deaf, huh?

AE: Yeah. And the teacher would sit at the piano and go BONG, and say, “What’s that note?” And everybody else would know but I wouldn’t. And I still don’t know. When people sit at the piano and go, “What’s that note?” Everybody else in the room always knows, I never know. But in school everybody had to like, stand in groups and sing this English folk song, hymns or something. And uh… I just couldn’t do it. I think I must have been in the wrong key.

(Laughs)

I: For real?

AE: Yeah… No one ever said, well why don’t you try singing it baritone. And that’s probably the reason.

I: You’ve certainly proved that teacher wrong.

AE: Well, I don’t know. I still don’t think I can sing but somehow I get away with it. But it takes a very long time to learn how to project your voice. How to make the most of your limitations. No, I really don’t know how to sing.

I: What about Bob Dylan then? He made an art out of it.

AE: Yeah. But I don’t like his singing. (Laughs)

I: I don’t either but I’m saying it’s just ridiculous what the guy’s been getting away with for twenty-plus years.

AE: I think one good thing about this new album is that you can’t tell that I can’t sing. It sounds okay… I think it sounds okay. The last album I think sounded too weird. Sounded like I had a sore throat. I don’t think my singing’s got better, but I got better at hiding the fact I can’t sing.

I: But is it hard to believe you’ve had the chance to make a career in music?

AE: It is when you’ve always been told not to believe in yourself. In any particular area. I mean I always truly believed that I should steer clear of being involved in music, because I was told I would not - it would be a complete waste of time.

I: Did it make you determined to make it in music?

AE: No, no… Cause I always thought that music is so silly. Pop music is, it’s so silly that… I don’t know. I’m a serious person. I really can’t do it. There’s not a way to provide… I always said that.

I: Don’t know if you did but if you ever went to see gigs when you were younger, you never thought you could be doing something like that-

AE: No. Never.

I: So it must be very interesting. What changed your mind?

AE: When I was twenty-one, someone left a drum kit in my cellar, where I was living, just to store it. And… While it was there I sort of learned to play. It was fun. I played it very badly, but it was fun. Then someone asked me to play on their record, because I was the only person who could play the drums in the whole of Leeds that could be relied upon never to hit the cymbals or to do tomtom rolls. Mostly because I was completely incapable of it. So I just played it like a glitter band, like PA-DUM, PA-DUM, like ten minutes at a time. And I was perfectly happy to sit there for ten minutes at a time just going, BA-DUM PA-DUM BA-BUM without any cymbals. None of that. They asked me to play on their record. And that’s how it started.

I: So who was the band?

AE: That was the very first Sisters record. On which all I did was play the drums very badly. I just wanted to sound like a glitter band. Nothing else. I was really very happy to be doing that. But then the guy that asked me to play drums on the record, he decided he wasn’t very good at singing. And he insisted that I have a go. And because we couldn’t buy a machine to do the singing but we could buy a machine - one of those tiny little boxes - to do the drums, that’s what happened. And that’s how the Sisters started.

I: So did Phil Collins before Phil Collins started. Drumming and singing.

AE: No, I can’t do two things at once. I’m still incapable of doing two things at once. I can’t even strum a guitar and sing at the same time. So you see why I can’t get on with musicians. People who find it totally unbelievable that a man can’t hit a chord, then sing a verse, then hit a chord, then sing a verse. I’m totally incapable of this and I’ve got very little respect for people that can.

I: I don’t really understand that point of view. I mean I find it ridiculous. To write a song you don’t need to be Jimi Hendrix, per se.

AE: Yeah but people will always turn around to you and say, “Well, what do you know? You can’t even play the guitar while you’re standing up.”

I: I can’t play the guitar but I can say what’s a good song and what’s a bad song.

AE: Yeah but musicians are different. Musicians are very different.

PM: Very, very delicate egos.

AE: Yeah.

PM: They have little security in what they do. They can’t handle that. Nobody wants to be told how to play by someone who’s going to say something like that.

I: So when you write songs, what instruments do you use?

AE: Usually guitar. Acoustic guitar.

I: Is it kind of written out - you’re usually done with it immediately?

AE: Yeah. But I’ve started using pianos instead, because it can all sound the same after a while if you just sit there with a guitar all the time. And I have machines now that can play the piano for me - 'course, I can’t play the piano properly but I like the sound of it. So. We’re doing something with that. That’s our 1959 stuff. That’s the first time I ever wrote with the piano. There are two songs which - one is quite old, one is quite new. But it’s important that it plays straight now, while all the things wrong with the new one are still fresh in my mind. Before I forget to learn the lessons…

I: If you had fourteen songs to choose from for the next album, you would be tempted to go back to that? Borrow off it?

AE: I’m going to go back to the old one.

I: Are you going to produce it yourself?

AE: I don’t know, that’s not an ideal situation. It’s far too much work. That’s nervous energy you consume if you produce it yourself.

Rudy Sassafras