#the great war

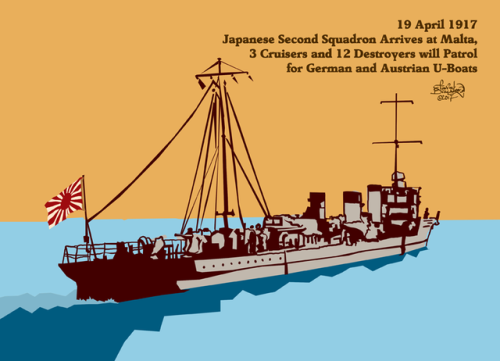

19 April 1917 - Japanese Second Squadron Arrives at Malta, 3 Cruisers and 12 Destroyers will Patrol for German and Austrian U-Boats

Post link

Soghomon Tehlirian (1896-1960), Talaat’s assassin, pictured in 1921.

March 15 1921, Berlin–The day after Turkey left the war, much of the Young Turk leadership, including Talaat, Djemal, and Enver Pasha, fled Constantinople with German help. In 1919, courts-martial established under Allied pressure in Constantinople sentenced them to death in absentia. Djemal had thence gone to Afghanistan and Enver to Moscow, but Talaat had remained in Berlin, and German authorities had no plans to extradite him to Turkey.

The Armenian nationalist Dashnaks decided to carry out justice for the Armenian Genocide themselves, and ordered assassinations of the leading Young Turks and other major figures deemed responsible for the genocide. On March 15, Soghomon Tehlirian shot Talaat as he exited his house in Charlottenburg. He did not attempt to flee the scene, and was promptly arrested.

At his trial, which included such witnesses as Liman von Sanders, Tehlirian testified:

I do not consider myself guilty because my conscience is clear…I have killed a man. But I am not a murderer.

After an hour’s deliberation, the jury acquitted him.

Sources include: Raymond Kévorkian, The Armenian Genocide.

Allied soldiers on parade in Düsseldorf.

March 8 1921, Düsseldorf–The Treaty of Versailles did not specify the amount Germany would have to pay in war reparations, but deferred the decision on the exact amount until May 1921; in the meantime, Germany would pay 20 billion gold marks and large quantities of coal and chemicals. With that deadline fast approaching, however, no agreement had been reached, or even seemed close; the Allies had proposed a figure of 226 billion gold marks in January, whle the Germans countered with 30 billion.

To back up their demands, on March 8, 15,000 French and Belgian troops occupied Düsseldorf and Duisburg; the British signed off on the operation but only provided a handful of troops themselves. The French claimed that the lowball German figure meant that the “German Government does not wish to fulfill the engagements it assumed in signing the treaty.” German President Ebert understandably protested:

Our opponents in the World War imposed upon us unheard-of demands, both in money and in kind, impossible of fulfillment. Not only ourselves but our children and grandchildren would have become the work-slaves of our adversaries by our signature. We were called upon to seal a contract which even the work of a generation would not have sufficed to carry out.

We must not and we cannot comply with it. Our honor and self-respect forbid it.

With an open breach of the Peace Treaty of Versailles, our opponents are advancing to the occupation of more German territory.

We, however, are not in a position to oppose force with force. We are defenseless….

Fellow-citizens, meet this foreign domination with grave dignity. Maintain an upright demeanor. Do not allow yourselves to be driven into committing ill-considered acts. Be patient and have faith.

Bolshevik forces attack across the ice towards Kronstadt.

March 8 1921, Kronstadt–The call for a partial democratization of the soviets by the sailors of the Kronstadt naval base was treated as a mortal threat to the revolution by the Bolsheviks in Moscow. Trotsky was sent to Petrograd, issued an ultimatum to the sailors, and took whatever family members he could find as hostages. On March 7, Bolshevik artillery began firing on Kronstadt, and on the wee hours of March 8, under cover of a snowstorm, infantry under Tukhachevsky attacked across the ice. It was worried that their loyalty was shaky, so behind them were Cheka and specially-picked units to make sure they did not flee. To the south of the island, artillery from Kronstadt blew holes in the ice and many of the attacking infantry fell into the freezing water. Some reached the island in the north, but were outnumbered and quickly repulsed.

On the morning of March 8th, the fourth anniversary of the start of the February Revolution, the sailors on Kronstadt were able to celebrate a victory over the Bolsheviks. Their own version of Isvestiapulled now punches in a statement that day:

By carrying out the October Revolution the working class had hoped to achieve its emancipation. But the result has been an even greater enslavement of human beings. The power of the monarchy, with its police and its gendarmerie, has passed into the hands of the Communist usurpers, who have given the people not freedom but the constant fear of torture by the Cheka, the horrors of which far exceed the rule of the gendarmerie under tsarism…

Sources include: Orlando Figes, A People’s Tragedy; W. Bruce Lincoln, Red Victory.

March 1 1921, Kronstadt–Aside from the distant reaches of the Far East, the Whites had been defeated, but severe threats to Bolshevik power remained and even intensified. Revolts spread across the countryside after a poor harvest added to years of hardship from Bolshevik grain requisition. In the cities, hunger became a major concern; by late January, the food ration provided to workers in Moscow and Petrograd was down to 1000 calories a day. Large strikes broke out in Moscow on February 21 and Petrograd the next day, calling for the reconvening of the Constituent Assembly, freedom of movement (most critically, the freedom to go into the countryside and trade for food there, a pattern that had become very familiar in Russia and Germany during the war) and other rights that had been denied by the Bolshevik government. The parallels with the final days of the Czar were undeniable.

The unrest soon spread to the Kronstadt Naval Base, whose sailors had been in the vanguard of leftist opposition to the Provisional Government in 1917. On February 28, the crew of Petropavlovsk,historically staunch Bolsheviks, issued a proclamation calling for new elections for the soviets, full political freedoms for workers, peasants, left socialists and anarchists, and allowing peasants to manage their own land as they see fit as long as they do not hire labor. The proclamation was undeniably left-wing (unlike the strikers in the city, they notably did not call for the Constituent Assembly), but was a clear call for democratization of the Soviets (albeit with participation still extending no further right than the left SRs) and an end to the Bolshevik dictatorship.

On March 1, a crowd of 15,000 met in Anchor Square and agreed for new elections to the local Soviet. The Bolsheviks sent Kalinin to try to defuse the situation, but he only attracted jeers. The next day, rightfully worried that the Bolsheviks would quickly try to take action against them, a Revolutionary Committee of five was elected to organize elections and a defense of the island.

Sources include: Orlando Figes, A People’s Tragedy; W. Bruce Lincoln, Red Victory.

Soviet forces on parade in Tblisi on February 25.

February 25 1921, Tblisi–With both AzerbaijanandArmenia now under Soviet control, the the Soviets quickly turned their attention to Georgia, which was still under control of a Menshevik-dominated government. On February 12, local Bolsheviks began attacking the Georgian military. Two days later, Lenin agreed that the Red Army should intervene, after repeated urging from Stalin, himself a Georgian. On February 16, the Red Army crossed into Georgia, and after an intense nine days of fighting, Soviet tanks (captured from the Whites and their British allies earlier in the Civil War) and armored trains broke through the defenses in the heights above Tblisi.

On February 25, the Soviets entered the city and the local Bolsheviks declared the establishment of the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic. The fall of Tblisi did not mark a complete Soviet victory in the Caucasus, however. Georgian forces, although quickly losing cohesion, were falling back towards the coast and Batum [Batumi]. Simultaneously, the Turks had taken advantage of the situation by seizing some disputed border areas, and they had their eyes on Batum as well. Meanwhile, in Armenia, nationalists had revolted against the Soviets and seized control of Yerevan.

The house in Washington DC where Woodrow Wilson lived out his retirement, purchased less than two weeks after the awarding of the Peace Prize.

December 10 1920, Kristiania [Oslo]–The awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize had largely been suspended during the largest war Europe had seen in centuries; the exception being the 1917 prize, which was awarded to the Red Cross. With peace largely concluded in Europe, in December1920 the Nobel committee awarded the 1919 and 1920 prizes. One was given to Léon Bourgeois, first President of the League of Nations and a long-time advocate for an international criminal court and the formation of an organization similar to (if not even broader in scope than) the League. The other was given to President Wilson, for his efforts in the creation of the League. The American ambassador to Norway accepted the prize on his behalf, and read a short statement by Wilson:

In accepting the honor of your award, I am moved by the recognition of my sincere and earnest efforts in the cause of peace, but also by the very poignant humility before the vastness of the work still called for by this cause….

I am convinced that our generation has, despite its wounds, made notable progress, but it is the better part of wisdom to consider our work as only begun. It will be a continuing labor. In the definite course of the years before us there will be abundant opportunity for others to distinguish themselves in the crusade against the hate and fear of war.

To the great disappointment of Wilson (and the world), the United States had not joined the League of Nations, and would never do so; the awarding of the Peace Prize swayed few minds.

The $29,000 in prize money was highly welcome in the Wilson household, and was a not-insubstantial increase to his savings. His term as President would end in a few months without a pension, and his health problems limited his potential to earn an income. Less than two weeks later, Wilson would purchase a house in Washington DC for his retirement–even with the prize money, his friends had to put up two-thirds of the $150,000 purchase price.

Sources include: Barbara O’Toole, The Moralist. Image Credit: By APK - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

Soviet troops entering Yerevan on December 4.

December 2 1920, Yerevan–Since the Turkish invasion in September, the Armenians had repeatedly suffered defeats. By the time a ceasefire was concluded in mid-November, they had lost most of their territory and faced a choice between a humiliating peace reducing them to a rump state around Yerevan, or complete annihilation. A few days later, the Soviets decided to take advantage of the situation and invaded the country. Ultimately hoping that Soviet backing might improve their position against the Turks, the Armenian government resigned in favor of local Bolsheviks on December 2; Soviet troops entered the city two days later; they would not leave until 1991.

November 15 1920, Geneva–The League of Nations General Assembly convened for the first time in its Geneva headquarters (later to be named the Palais Wilson after the President’s death in 1924), with representatives from 42 states. More notable, however, with the absences.

The United States, having never ratified the Treaty of Versailles, was not present, and did not even send an observer to the proceedings.

None of the defeated states–Germany, Austria, Hungary, Bulgaria, or Turkey–were League members, though Austria and Bulgaria would join the next month.

Russia was not present, as the Allies did not recognize the Soviet government and the Whites had largely been defeated. Apart from Poland, the states that had broken off from the Russian Empire were also absent: Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and the embattled Armenia and Georgia—though Finland would be admitted the following month.

Some other states were also not present, due to oversights or because they were not in any way part of the Allies: Mexico, Ecuador, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Luxembourg, Albania, and Ethiopia, along with European microstates such as Andorra. British dominions (including India but not Newfoundland) each had their own representation in the League.

White soldiers on board one of the ships leaving the Crimea.

November 14 1920, Sevastopol–The Soviets had launched what they hoped to be their final offensive against Wrangel in late October. Although they destroyed much of his army, enough of it was able to fall back to the narrow isthmus connecting Crimea to the mainland to mount a concerted defense. This, however, was overcome by direct and amphibious attacks between November 7 and 11, and it became quickly apparent that Crimea would soon be lost.

Wrangel had been preparing for such a possibility since his arrival in the spring, however, and he was much better equipped than Denikin had been when evacuating the Kuban in March. Wrangel left Sevastopol on the 14th, and simultaneous evacuations took place at at least four other Crimean ports. 146,000 White soldiers and refugees were taken across the Black Sea to Constantinople by the end of the evacuation efforts on the 16th, aided by a one-day pause by regrouping Soviets.

Those who did not or could not evacuate, however, met a grimmer end. Béla Kun was put in charge of Soviet administration in the area. The Cheka killed tens of thousands in the coming weeks. In Kerch, “trips to the Kuban” were organized: prisoners were taken out into the Sea of Azov and pushed overboard to drown.

Those who evacuated were interned and then lived in exile. Wrangel took with him the last of the Blask Sea Fleet, including the dreadnought General Alexeyev, were interned in French Tunisia until the French recognized the Soviet Union in 1924.

Sources include: Evan Mawdsley, The Russian Civil War; W. Bruce Lincoln, Red Victory.

November 14 1920, Athens–Venizelos, Prime Minister of a united Greece since the Allied-enforced end of the National Schism in 1917, hoped that Greece’s gains from the war would win his party a continued majority at the polls in November 1920, the first non-boycotted elections since June 1915. These aims were complicated, however, by the sudden death of King Alexander to a monkey bite in October and the prospect of a return of his father, the exiled King Constantine. The elections then became not only a referendum on Venizelos, the peace terms, and the continued Greek involvement in Turkey, but the question of the succession and of the monarchy as a whole.

The elections were held on November 14, and the results were clear by the next day. Venizelos’ Liberal Party had been dealt an overwhelming defeat, winning only 110 seats out of the 370 in the Greek parliament, with all other parties decidedly opposed to him Venizelos even lost his own seat (though he was standing in Piraeus, not in his home of Crete). All of this was despite the fact that the Liberal Party won a majority of votes cast–presumably it was overwhelmingly popular in the areas that had been added to Greece in the last ten years, but narrowly lost most seats in the Greek heartland.

King Constantine would return as King in December after a he overwhelmingly won a (possibly-rigged) referendum. The Allies, especially the French, who had arranged for his ouster in 1917, largely stopped supporting Greece. Despite the anti-Venizelists’ opposition to continued military involvement in Turkey, the new government found it impossible to cleanly withdraw, and continued their efforts there for nearly two more years, albeit without Allied support.

Italian gains from the Treaty of Rapallo, shown in light green and yellow. Not shown are some other Dalmatian and Adriatic islands, and the port of Zara [Zadar]. Fiume is shown in yellow, as it was annexed by Italy in 1924; between 1920 and 1924, however, it was a Free State.

November 12 1920, Rapallo–After the signing of the Treaty of Sèvres, the last major formal loose end was the border between Italy and Yugoslavia. Italy had substantial claims along her eastern frontier and the Dalmatian coast, dating back to the 1915 Treaty of London under which she joined the war, but many of these areas had Slovene or Croat majorities, which under the Wilsonian principle of self-determination should go to Yugoslavia—which was as much an Allied signatory of the post-war treaties as Italy was. Wilson frustrated Orlando repeatedly at the peace conference, precipitating the latter’s withdrawal andlater ouster as PM, and the negotiations in Paris broke up before resolving the issue.

In early November, however, the Yugoslavs lost their American backers, as Wilson’s Democrats were defeated in a landslide. Harding had since disavowed the notion that the war was fought to make the world safe for democracy, and could not be counted on to support Slovene and Croat calls for self-determination. On November 12, Yugoslavia signed the Treaty of Rapallo with Italy, giving Italy control of Gorizia, Trieste, the entire Istrian peninsula, the western quarter of modern-day Slovenia, most of the islands off the Dalmatian coast (with the main exception of Krk), the small Pelagosa [Palagruža] islands, and the port of Zara [Zadar]. Notably not included was the port of Šibenik, which had been offered to the Italians in a final compromise offer before Orlando was ousted. Fiume [Rijeka] was to become a free city, like Danzig; before that could come to pass, D’Annunzio, who had occupied the city and demanded Italian annexation, would have to be dealt with.

Sources include: Mark Thompson, The White War.

The Cenotaph, pictured between 10:30 and 11AM on November 11, 1920. The casket of the Unknown Warrior, drawn by a gun carriage, is partially obscured behind a tree.

November 11 1920, London–The official Victory Parade, celebrating the Allied victory in the war, was held in July 1919. It featured a cenotaph–an empty tomb–commemorating all the soldiers of the British Empire who had fallen overseas, their bodies buried there. The 1919 cenotaph was a temporary construction, but it was so popular (over a million people visiting the structure in the week after the parade) that there were soon calls for a permanent version.

The permanent Cenotaph, built on the same site in Whitehall as the temporary one, was built between May and November 1920, ahead of the unveiling on the second anniversary of the Armistice. As part of the ceremony, it was also decided to exhume an unidentified British soldier from France and bury him as the Unknown Warrior in Westminster Abbey (not in the Cenotaph itself, which was intentionally empty).

At 11 AM, exactly two years after the Armistice went into effect, King George V pulled a lever, revealing the Cenotaph from under the two large Union flags that had covered it. The crowd stood in silence for two minutes, the “Last Post” was sounded on bugle, and the King laid a wreath before the unveiled cenotaph before the procession continued to Westminster Abbey. There, the pallbearers, which included Marshals Haig and French and Admiral Beatty, bore the casket inside, where it was interred after a brief and solemn ceremony.

Until closed at midnight, crowds filed by both the Cenotaph and the tomb in Westminster Abbey. Within a week, well over a million had paid their respects, and the Cenotaph was partially buried in a pile of wreaths and flowers over ten feet high.

Harding Wins in a Landslide

The 1920 Presidential Election results, with red for Republican Harding, and blue for Democrat Cox. Darker shades indicate states won by larger margins.

November 2 1920, Marion–Campaigning on a “return to normalcy” after the war, the Red Scare, the Red Summer, and economic upheaval, Republican Senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio won the presidential election on November 2 in a landslide of unprecedented scale. His 60.35% of the vote was the largest share of the vote won since the last uncontested election in 1820, and his 26.2% margin over Democrat James Cox is still the largest in a US presidential election. Cox only won Kentucky and 10 of the 11 states in the former Confederacy (Harding won Tennessee), the largest electoral college landslide since Reconstruction. Winning 3.41% of the vote (down from 5.99% in his 1912 run) was Socialist Eugene Debs, who ran his campaign from a prison cell. Harding’s popular vote total was over 75% larger than Wilson’s winning vote total four years earlier, a testament both to his landslide and the many new women voters enfranchised by the 19th Amendment.

Apart from usual Republican strongholds like Vermont, Harding’s win was biggest in the Upper Midwest: North Dakota, Minnesota, Iowa, Wisconsin, and Michigan all gave him over 70% of the vote. Hughes had won most of these states four years earlier, but he had won Minnesota by less than 400 votes and Wilson had won North Dakota. The war and Wilson’s handling of the German peace terms had apparently destroyed Democratic chances with German voters in the area. Wilson had hoped the campaign would be a referendum on the League, but Harding was noncommittal on the issue, and Cox eventually backed reservations on Article 10. On October 27, Wilson gave his first speech since his stroke, in support of the League, in front of an audience of 15 who still struggled to hear his words; he did not mention Cox at all. Wilson’s mishandling of the Senate had doomed the United States’ chance to enter the League long before, and Harding’s election heralded the United States’ general withdrawal from world affairs.

Sources include: Patricia O’Toole, The Moralist. Image credit: uselectionatlas.org

October 28 1920, Kakhovka–As the war against Poland wound down (ending in an armistice in mid-October), the Soviets had been moving forces south to deal with the last major White force opposing them, Wrangel’s troops in North Taurida and Crimea. On October 28, Budyonny’sKonarmia broke out from the Kakhovka bridgehead, hoping to cut off the rail lines between Wrangel’s forces and their refuge in Crimea. Wrangel had known he was in danger of being cut off, but had kept his forces in North Taurida to secure food from the harvest in that area. Soviet infantry also advanced across the Dnepr and pushed south at a slower pace.

The offensive did force the surrender of well over half of Wrangel’s forces, but within five days, the remaining portion (including his most experienced troops) had managed to escape into Crimea, exactly what Frunze had feared. Wrangel was still in firm control of Crimea, and the situation was much the same as it had been in the spring–just without the looming threat of a war with Poland.

Sources include: Evan Mawdsley, The Russian Civil War.

King Alexander of Greece (1893-1920, r. 1917-1920)

October 25 1920, Tatoi–In 1917, Allied pressure had forced Greek King Constantine to abdicate and leave the country, along with his eldest son, George, as they were perceived as being too pro-German. Constantine’s second son, Alexander, took the throne, and Greece joined the war on the Allied side soon thereafter. Greece was richly rewarded for its participation, receiving Bulgaria’s southern coast (the port of Dedeagach being renamed Alexandropouli for the King), European Turkey outside of Constantinople, the islands of Imbros and Tenedos, and effective control of Smyrna and its environs. Prime Minister Venizelos called for new elections for early November, hoping the gains from Sèvres would lead to an increased majority for his party in the first elections since 1915.

On October 2, Alexander was walking with his dog, Fritz, a German Shepherd, when the dog became embroiled in a fight with a Barbary ape kept on the grounds of the royal estate. Alexander attempted to separate the two, but was bitten by a second monkey in multiple places. These wounds would soon become infected, and on October 25, Alexander died of sepsis at the age of 27.

The unexpected death of the young king triggered a succession crisis. Constantine wanted to return to the throne, but Venizelos was understandably opposed to both Constantine and George. The throne was instead offered to Alexander’s younger brother, Paul, but he refused, saying the exclusion of his father and brother from the succession was illegal. Venizelos considered inviting a foreign noble from a different house; foreign press speculated that the candidates might include Prince Sixtus of Bourbon-Parma (who had played a role in Austrian peace overtures in 1917) and King George V’s uncle, Prince Arthur. Another possible candidate existed, though it is unclear who was aware of it at the time; King Alexander’s wife was four months pregnant, and the unborn child could succeed their father posthumously. Alternatively, the monarchy could be abolished entirely.

The upcoming elections, though pushed back by a week, suddenly became a referendum on the future of the monarchy. The divisions of the time of the National Schism had never healed—Venizelos was nearly assassinated at the Gare de Lyon while returning from the signing of the Treaty of Sèvres—and they flared up dramatically with the prospect of Constantine’s return.

October 16 1920, Riga–After defeats on the Vistula and the Niemen, the Soviets were ready to sue for peace with Poland before losing any more territory. Likewise, Poland had learned their lesson from their misadventures in Ukraine earlier in the year, and wanted peace from a position of strength, without overextending themselves too far once again. On October 12, the Poles and Soviets agreed to an armistice. However, it would not go into effect for several days, and both sides spent the last few days of fighting securing as much territory as they could, as the armistice line could very well determine the ultimate negotiated frontier. The Poles still had the upper hand here, and on October 15 they captured Minsk from the Soviets. The ceasefire entered into general effect on the 16th, though limited fighting continued until the 18th in some areas.

The ceasefire, however, did not apply to Poland’s allies–Petliura’s Ukrainians and smaller forces of Belarusians and Whites. However, these forces found themselves highly outnumbered without explicit Polish support, and these groups were largely defeated and forced into exile by the end of November.

An Austrian propaganda poster, in Slovenian, reading “Mother, do not vote for Yugoslavia, or I will be drafted for King Peter.”

October 10 1920, Völkermarkt–TheTreaty of Saint-Germain called for a series of plebiscites in Carinthia to resolve the disputed Austrian-Yugoslavian border. The first one, for the immediate border region, was held, after some delay, on October 10. Although the region was majority-Slovene, Austria won the plebiscite 22,025 - 15,278. The region had stronger economic ties to the rest of Austrian Carinthia than to Yugoslavia, many saw Austria as more forward-thinking than Serbian-dominated Yugoslavia, and Austria, unlike Yugoslavia, had no conscription (as a result of the Treaty of Saint-Germain).

The result was something of a surprise to both sides. In protest, Yugoslav forces briefly moved into the plebiscite area the next week, but quickly withdrew; the government in Belgrade was not greatly concerned with Slovenia’s borders. Plans for a second plebiscite, for the city of Klagenfurt and its surrounding environs, were cancelled as the results of the first hand rendered them moot.

Sources include: Margaret MacMillan, Paris 1919.

Polish soldiers in Vilnius.

October 9 1920, Vilnius–After the Polish victory outside Warsaw, the Poles could once again turn their attention back to Lithuania, where Polish ambitions had been checked a year before. In early September, Poland protested to the League of Nations about Lithuania’s complicity in the Soviet invasion of Poland, and the League attempted to mediate the ongoing dispute between the two countries. While negotiations were proceeding, Polish forces brushed aside Lithuanian troops to outflank Soviet positions on the Niemen. The annoyed the League, who demanded a ceasefire between Poland and Lithuania.

On October 7, a ceasefire was agreed to, along with a demarcation line between Polish and Lithuanian troops. However, its eastern progression abruptly ended at Bastuny, on the railway line leading south from Vilnius, as Poland demanded freedom of action further east to fight the Soviets (although ceasefire negotiations between Poland and the Soviets were well underway).

Piłsudski wanted to take Vilnius for Poland, but realized this would be unacceptable to the League. He instead arranged for Lucjan Żeligowski, a division commander, to “mutiny” and seize the city, taking inspiration from D’Annunzio’s seizure of Fiume in 1919 with covert backing from Badoglio. The Lithuanians, outnumbered by Żeligowski’s forces and the majority Polish population of the city, fell back, and the city came under Żeligowski’s control on October 9. Three days later, Żeligowski declared the existence of the Republic of Central Lithuania, which he would rule as an effective Polish puppet state until Poland annexed it two years later.

Sources include: Margaret MacMillan, Paris 1919; Prit Buttar, The Splintered Empires.

October 6 1920, Kakhovka–Sincebreaking out of Crimea in early June, Wrangel’s front had largely stabilized, covered by the Dnepr in the north (excepting a Soviet bridgehead established around Kakhovka in August). Attempts to land in the Kuban and reconnect with Denikin’s old power base among the Cossacks there had failed. On October 6, Wrangel tried one final offensive, pushing north across the Dnepr. There was, at least initially, some hope that the offensive would encourage the Poles to move into Ukraine as they had earlier in the year. However, the Poles had learned their lesson in the spring and were already negotiating an armistice with the Soviets.

The Soviets, although they were desperately trying to prevent the Poles from taking territory before a possible armistice, had already begun moving troops south to face Wrangel. However, they were slow in coming–Budyonny’s Konarmiahad been wrecked by months of fighting, culminating in their near-destruction at Komarów, and it would take them nearly a month to move south. They still managed to find time to conduct pogroms on the way, however.

As a result, Wrangel’s forces were able to cross the Dnepr and make limited progress. However, even without the incoming reinforcements, the Soviets still outnumbered the Whites, and Wrangel’s troops had to withdraw back across the river within a week. It would be the last major White offensive in the civil war.

Sources include: Evan Mawdsley, The Russian Civil War