#thisiswhatasexuallookslike

Not gonna lie, I was pretty dang star-struck when I spoke with Yasmin Benoit. She’s an internationally recognised alternative model, academic and LGBTQ+ activist. Yasmin identifies as aro-ace, which is short for aromantic asexual. Through modelling, public speaking, writing and research, she’s shaking up the mainstream perception of these queer identities in massive ways, as well as promoting the visibility of queer people in colour.

U: Hi Yasmin! For those readers who may be less familiar, could you give us a description of what it means to be ‘aro-ace’?

Y: I’m sure you’ll find some people with different meanings, but asexuality is most commonly defined as experiencing little-to-no sexual attraction. Some resources mistakenly say that it’s having no sexuality, or no sexual feelings or desires, but it has nothing to do with that. It’s specifically about experiencing a lack of sexual attraction. It’s a sexual orientation, just one that isn’t really oriented anywhere.

Being aromantic is most commonly defined as experiencing little-to-no romantic attraction. I’ve never been inclined towards romantic relationships, nor do my emotions or connections manifest that way. I place that same energy into platonic relationships. People tend to think that being asexual and aromantic go hand-in-hand, and while it did for me and there is definitely a significant overlap in the communities, there are lots of asexual people who aren’t aromantic and aromantic people who aren’t asexual.

U: You’ve spoken openly about your teenage years, and how friends would ask pretty personal questions about your sexuality before you had discovered the terms ‘asexual’/’aromantic’. Do you think the kinds of questions people ask are shifting now that the terms are more accessible? And if so, how?

Y: Honestly, the questions I get now and the questions I got back then really haven’t changed. The mistakes people make are the same, but since they’re not teenagers, people offline usually aren’t so likely to be as blunt about it. People online, not so much!

Sometimes it seems like asexuality has been caught in some kind of groundhog day.

Like, I can watch interviews that activists did in the media in the early 2000s and the questions they get are the same, albeit delivered in a less politically correct way.

Most people are familiar with the term ‘asexual’ because it’s an old term and it’s been on the outskirts of conversations for decades at least; people just don’t have the inclination or intrigue to look into what it truly means because it’s often treated as an irrelevant aspect of human sexuality. Romantic orientations are still such a new conversation that aromanticism is even further behind asexuality.

U: You’ve achieved a HUGE amount over the course of a few years, from press features to conferences. What is your proudest accomplishment?

Y: It’s quite hard to choose! When you go into things not expecting to achieve much, even the little things feel quite remarkable. If I had to narrow it down, I’d probably say either Prague Pride 2019 or Ace of Clubs in 2019 (that was a good year).

I really like doing the kind of work where I can create in-real-life memories for asexual people in spaces that they wouldn’t usually have.

Prague Pride was my first time working at an international Pride event, I was invited as a special guest and was doing TEDx-style talks and hosting events. It was pretty nerve-wracking doing all of that in a country I’d never been to, so it felt like an achievement that I even managed to pull it off. It was the first time they’d had an asexual special guest and ace-centric events, and it lead to a really big turnout of asexual people and increased our visibility there.

Ace of Clubs was the first ever asexual pop-up bar, which I hosted during London Pride in 2019. It was a two-day event that provided the only asexual space at the entire festival, we had a panel, a projection screen, food, an open bar, music, games… It gave asexual people the chance to meet each other in person – which some had never done before – and party together in a safe space. So I was really proud that I had the chance to bring that to fruition. People still ask me about Ace of Clubs a lot and I still have a lot of lovely supporters in the Czech Republic! Hopefully I can bring the bar back and visit Prague again in the future.

U: You’ve been dubbed the “main face of asexuality.” How does it feel to be called that?

Y: It’s pretty crazy. It isn’t a position I expected to be in and it took me a little too long to realise that people were being serious when they said that! It’s flattering, for sure, if I think of it as recognition for all of the work I’ve been putting in. It’s also quite a lot of pressure, because people are always looking for me to do something incredible and life-changing for everyone. There’s also a lot more eyes on me, regarding what I do, what I say, how I conduct myself, who I work with, what I post etc, which makes it harder for me to just relax and be unguarded as a member of the community. So there’s pros and cons. But it’s an honour to have that kind of recognition and I do my best to use that attention in a way that’s beneficial to the entire community.

U: A focal point of your activism has been to change people’s perceptions of what asexuality looks like through alternative lingerie modelling – which, by the way… ICONIC. You even coined the hashtag #ThisIsWhatAsexualLooksLike. Since you started this journey, what kind of progress have you seen?

Y: Haha, thank you! I like to think there’s been some progress. I think my modelling has allowed me to discuss asexuality in quite sexualised spaces where it wouldn’t usually come up and bring it to the attention of a different audience.

I’ve definitely noticed an increase in asexuality being talked about in sex-positive communities and I’ve been grateful to have the chance to fill that void myself.

The hashtag has really turned into more of a campaign or movement for asexual visibility. It’s become a way for the community to represent themselves without having to rely on the media to do it. It’s been amazing to see it take on a life of its own and be used on so many platforms, including those I don’t use. I think it’s really helped some aces be able to feel more empowered in their self-expression, based on what I’ve heard. It’s also a series that I write for a website called Qwear Fashion, where I interview ace people about their stories and style! It’s on it’s tenth edition now.

U: What does you-time look like for you? What do you do in your spare time – if you have any spare time?!

Y: When your work isn’t structured in a typical 9-5 way, it can be particularly hard to switch off. Spare time often just feels like time when I should be doing something constructive, whether it’s doing extra work on a project or finally answering my Instagram comments. I’m probably spending it playing far too much Sims 4, reading some history book, going out for something to eat or wandering around a forest in the countryside somewhere. The last one really is a treat.

U: So on top of all the other things you’re doing,you’re also a researcher at California State University. Tell us a bit about the sort of research you’re carrying out and the headway that’s happening there.

Y: There’s a researcher at California State University, San Bernardino conducting research into families and relationships among asexual people, I’m part of the research advisory board and their research team. I do the coding and analysis for the transcribed interviews. I was always interested in the academic side of asexuality activism and I’m definitely hoping to get my name on a research paper someday. This is my way of dipping my toes in. And to anyone reading this and thinking, ‘Why get a model to do research?’ I have an MSc Crime Science degree and a BSc Sociology degree, so it’s actually right up my alley!

U: What advice would you give those who are questioning their sexuality based on your experiences?

Y: I guess first and foremost, I’d say that

sexuality isn’t as black and white as we often think it is.

Every single person’s sexuality is different, multi-layered and fluid to some degree. When we’re talking about our sexual orientation, romantic orientation, desire, libido, arousal, preferences, all of those things – there is no blueprint, despite what we’re taught. There is no typical way to experience sexuality. It’s that idea which makes many queer people – including asexual people – feel like they’re abnormal or missing something.

It’s okay to question your sexuality, in fact, it’s healthy to do that. If you want to analyse it, do that, but through the lens that there isn’t necessarily anything wrong with what you are or aren’t experiencing. And if you find a term that helps you describe what you’re feeling and you want to use it, use it! Don’t worry about having to spend your entire life using it. And if you don’t want to use any terminology or label, don’t. You don’t owe anyone a clear-cut answer and it’s entirely possible to live happily without neatly fitting into any of these preconceived sexuality boxes. I do it all the time.

U: And what does a good aro-ace ally look like? What can they do and say to support the aro-ace community?

Y: Include us in conversations, amplify our voices, support our work and help to normalise our experience! If you’re speaking about sexuality and relationships but you aren’t including asexuality or aromanticism then you’re missing out a significant chunk. The latter includes the least amount of effort and actually makes a huge difference.

U: So… what’s next for Yasmin Benoit?

Y: Depending on when this comes out, I’ve got a considerable line-up of talks, online appearances, and photo shoots scheduled for in-or-around Ace Week!* So that’s what’s immediately next. But the fun thing (and the unsettling thing) about my job is that I never know what’s around the corner! There’s some things that should be coming that I can’t announce yet and some I’m actively working towards, but I don’t want to jinx it. With the support and encouragement of the aro/ace community and our allies, I’m sure there’s good things on the horizon!

https://unicornzine.com/cover/the-face-of-aro-ace-lets-get-to-know-yasmin-benoit/

“At the forefront of the Asexual visibility movement is British Model Yasmin Benoit, who you’ve most likely seen online looking incredible whilst making ace-history. As the creator of #ThisIsWhatAsexualLooksLike, their work often brings light to many asexual misconceptions and shows you that being Asexual doesn’t look just one way. To celebrate Asexual Awareness Week, Yasmin has made history by collaborating with Playful Promises to create the first-ever Asexual theme lingerie campaign!” - Unite UK

What is a common misconception about asexuality that you wish to debunk?

A common misconception that I try to challenge when incorporating activism into my modelling is this pervasive idea that there’s an asexual way to look or dress. It’s a message I’ve received ever since I started being more open about my asexuality - people would say that I ‘didn’t look asexual.’ Because I was a young Black girl, because people thought I looked nice, because I put some effort into my appearance.

There’s this belief that if you’re not sexually attracted to anyone, then it’s either because you’re sexually unattractive and no one would want you, or you should make yourself sexually unattractive, as not to attract any kind of attention. It can be quite a dangerous mentality, because it means that asexual people looking attractive is somehow extra provocative and trigger more aggression in others. This strange, frumpy asexual stereotype can make asexual people feel like they can’t experiment with fashion and express themselves through it the same way as everyone else can. I don’t think your sexual orientation needs to determine the way you dress.

What is the significance of having an asexual lingerie model?

Lingerie is associated with sexuality, it’s seen as being a sex-positive thing and it’s associated with embracing your sexuality. It’s also associated with feeling sexy for other people. I think having an openly asexual model who loves lingerie, but not for sexual reasons, shows the many ways that you can appreciate these kinds of designs. It also includes asexuality within a sex-positive space, which I think is really important, as we’re often left out of those because of the assumption that we have no sexuality, no sexual interests, or that we’re inherently anti-sex.

It’s also really significant for me personally, because queer people - particularly queer racial minorities - are taught to dim parts of ourselves to stay palatable, employable and avoid stigma in our respective industry. Being openly asexual isn’t necessarily going to please everyone or make them want to work with you, it can have the opposite effect. To have the chance to to blend the theme of the asexual flag into the photo shoot for a well-established lingerie brand is amazing. I haven’t seen a lingerie brand ever do that before, so it’s great to be part of a historical moment. I hope it makes other asexual people feel seen and empowered.

How does lingerie help you express yourself?

I’ve always had quite an unusual style, I don’t like limiting myself to anything. Growing up interested in alternative and gothic subculture, I always saw things like corsets, stockings, big boots and things like that as being integral parts of a cool outfit. I also used to be really into video games and professional wrestling, where the women were always wearing something very akin to lingerie and kicking ass doing it. I guess it made me associate those looks with being powerful, and it was something I wanted to incorporate into my own style. So when I wear it, I feel like I’m channelling that energy. Lingerie is the closest thing you can get to a straight-up superhero outfit without going full Comic-Con. Unfortunately, you can’t walk around every day in lingerie but photo shoots give me the opportunity to experiment with it and feel like I’m capable of back-flip-karate-kicking a giant man out of an arena.

What advice would you give to someone who identifies as asexual and is yet to “come out”?

Other people’s reactions to you aren’t a reflection of you, it’s a reflection of what they don’t know. There’s a chance that people will completely get it and accept it right away, and there’s a chance that they won’t do that, but the latter doesn’t mean that it’s hopeless. It takes some people a while to understand. I also recommend that asexual people yet to come out prepare themselves for doing it often, as it isn’t the kind of thing you just have to do once. It can be helpful to have some resources you relate to on hand, as people sometimes understand and accept asexuality more when they can see that it’s a genuine sexual orientation that other people experience, not just a random word you heard on Tumblr one time. Finally, it’s important to know that coming out isn’t essential. You don’t have to share the intricacies of your sexuality with anyone, not everyone is entitled to that information. If you don’t want to use a label or tell people about it, or if you just want to keep it on a need-to-know basis, that’s your right too.

How do you wish asexual people were more included in events such as Pride?

For me, it isn’t just about including ace flags in the corporate side of Pride, it’s expanding our idea of what Pride is and how the asexual experience relates to it. Asexual people have always been part of Pride, we might not have experienced the same systemic oppression as other identities, but we have the similar experience of having a pathologised, stigmatised identity which has lead to us being taught that there’s something inherently wrong with us. It’s something we have to unlearn and Pride is all about embracing the parts of your sexuality that our society has taught us to be ashamed of. I wish that we could expand our understand of queerness outside of who wants to have sex with who and how. That way, there would be less debate about asexual inclusion and it’d happen organically, and people would put the same effort into representing the asexual community as all the others. Personally, I’d love to be able to do what I did in 2019 when I opened the first asexual bar at London Pride without our inclusion sparking questionable think-pieces about whether or not we should be allowed to be there.

Where do you want to see the Ace community in five years time?

I just hope that we get out of this weird groundhog day that we’ve been in for like…twenty years. Sometimes it feels like we’re making progress, and we are, but at a much slower pace compared to other identities. The way we discuss sexuality has expanded a lot but it hasn’t become very inclusive of asexuality yet. The kind of questions that I get as an activist now are strikingly similar to those I saw asexual activists getting in the early 2000s. We’re still in a 101 introductory stage as if this orientation is some kind of new fad. I hope that in five years time, we’re way past that and asexuality is more normalised. Then we can get into more interesting conversations and incorporate asexuality into how we understand sexuality in general, which will surely benefit everyone.

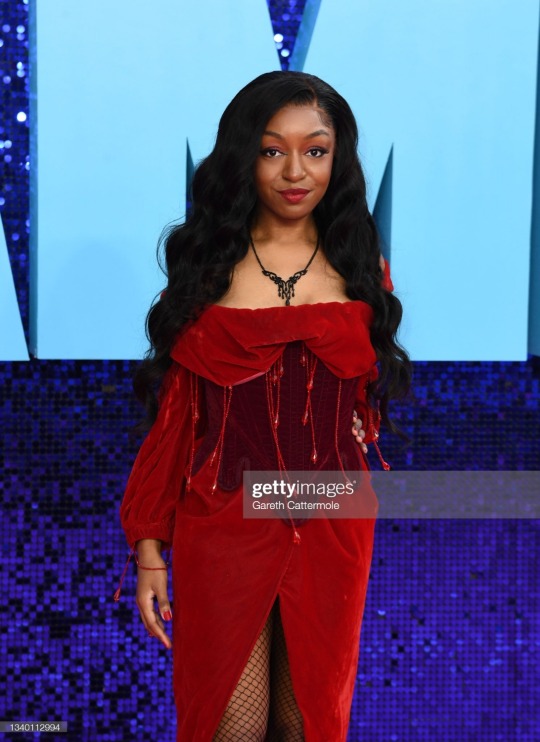

My red (or pink) carpet debut! It was incredible to be invited to the world premiere of Everybody’s Talking About Jamie!

I actually graduated with my Masters degree in this exact same building in 2019. I never expected to return for something like this. I never expected to find myself, or see someone like myself, in this kind of space. I was honoured to have the opportunity to provide some Black aromantic asexual representation for all of those who, like me, have ever felt invisible.

I wanted to serve some gothic vampire glamour because my younger self would have loved to see a Black girl on a ‘red’ carpet in fishnet tights and platform boots, like the early 2000s rocker girls that inspired me. Thank you all who have continued to follow me on this increasing wild ride and those who helped to make last night so special! ❤

I’m honoured to announce that I’m the winner of an Attitude Pride Award! Not only is this the first time I’ve won anything in my life, it’s the first time an aromantic-asexual activist has won an LGBTQ+ award in this country!

In 2017, I publicly came out as asexual on my social media without really thinking that anyone would care about what I had to say. By the time I finished my Masters degree in 2019, I decided to dedicate myself full time to my activism with no idea of where it would lead or if it would amount to anything other than rendering myself completely unemployable. I’ve put my safety, sanity, financial security, reputation and relationships on the line to serve the aspec community. What you see on social media is just the seemingly glamorous highlights (and a small glimpse at the downsides), but make no mistake, I’m just a volunteer, not a celebrity with a team behind me.

To have my work recognised by an iconic publication like Attitude Magazine isn’t just monumental for me, it’s making a powerful statement about inclusion! I dedicate this to the unsung heroes of the aspec community. From the chatroom mods, to the historians, the researchers, the event planners, page runners, meme makers, the flag designers, the advice givers, the stall-runners, the newcomers, the elders and the low-key game changers. And of course, to my mother for the emotional (and financial) support that has made this work do-able!

Thank you to Attitude Magazine and to all for your continued support and for making this school loser feel pretty damn cool. The Summer special edition of the magazine is on newsstands now! Watch my video interview below:

More often than not, the letter ‘A’ hanging out at the end of the LGBTQIA+ acronym is either overlooked or, worse, ignored.

Although representation and visibility is improving, asexuality (applied to a person who does not experience sexual attraction) is still met with confusion.

With that in mind, Attitude asked asexual activist, model and writer Yasmin Benoit to lead a conversation about her community with two other asexuals, Daniel Walker and Richard Ng, in the Attitude Sex & Sexuality issue, out now to download andto order globally.

Shining a light on the different shades of asexuality, the trio unravel the knottiest issues they have had to face – including the most maddening misconceptions…

Yasmin Benoit - 24, asexual and aromantic (not desiring of romantic relationships at all)

“I have overwhelmingly been met, after I initially came out, with straight-up disbelief… It can get some messy reactions; I’ve had times where I’ll be sitting at someone’s house, drinking a cup of tea, talking about a TV show, and then the next thing you know, I’ve got six people asking me about how often I masturbate and what’s that like.

"I’m like, ‘I’m just here to drink a cup of tea, that’s not what we’re doing today’. It invites some very inappropriate, sometimes aggressive, sometimes very uncomfortable reactions.

"Whenever people say to me, 'If you haven’t had sex, you can’t know’ – especially if a guy says that, a straight guy – I’m, like, 'Well, how much gay sex did you have before you realised you were straight?’ Usually, you quickly find that they didn’t have much gay sex before they determined they were straight.

"Also, when they say you haven’t found the right person yet – there are loads of asexual people who have found the right person and they’re still asexual; they’re in love with the person, they have a family with the person, they’re in a platonic relationship, they’re soulmates.”

Daniel Walker - 24, asexual and homoromantic (romantically by not sexually attracted to the same gender)

“I definitely see people assuming it’s a mental health issue, or you’re depressed, that’s what’s causing your asexuality. Or even in some extreme cases, that when they find out someone is asexual, they assume someone must have been traumatised.

"What I have seen quite a lot recently is the misconception that asexuality means that the person is inherently non-sexual.

"What I mean by that is, asexuality is defined by a lack of sexual attraction, but that is completely separate from a lot of other things which are sexual; for example, having sex or masturbating or watching porn or even dressing in a way that society would see as sexual.

"People assume that if you’re asexual, you must completely desexualise your appearance, and you can’t masturbate and you can’t watch porn, whereas I feel like – I don’t know, it’s not a standard other orientations are held to.”

Richard Ng - 25, asexual and heteroromantic (romantically but not sexually attracted to the opposite gender)

“For me, the biggest [misconception] is this idea of, 'You couldn’t possibly know that you’re asexual, because sex is a good thing and if you had experienced it…’

"There’s lots of things in that: Firstly, equating sexual orientation with sexual activity: I personally don’t engage in sexual activity, but obviously some asexual people do… If I say I’m asexual, they’ll refuse to accept it because, as it happens, I’m a virgin, I’ve never had sex, and they will read into that 'Oh well, you are naive about this, you couldn’t possibly know that you’re asexual, you’ve just not met the right person’.

"My parents are actually GPs and when I first came out to them, I can’t remember exactly how, but there was this sort of like, 'Maybe you need to see someone about this’. I don’t know, latent testosterone or something like that.”

Read the full feature in the Attitude Sex & Sexuality issue, out now to downloadandto order globally.

Subscribe digitally to the Attitude mobile and tablet edition for just over £1 per issue (limited time only).

IT’S OFFICIAL, I’M A TEDX SPEAKER!

I’m incredibly grateful for the opportunity to discuss asexual representation in the media on such an esteemed platform. Thank you to everyone, particularly Adam Key, who made this possible in a national lockdown. I hope you like it. I’ve been waiting a while to say this… Thank you for listening to my TED Talk!

Activist and model Yasmin Benoit dispels the myths around asexuality, ‘the invisible orientation’.

The conversation around sexuality and the spectrum of gender identity has expanded greatly in recent years. We’re finally beginning to explore all of the details, nuances and diversity of the topic, and acknowledging communities that have too long been shunned by society. But there’s one community – my community – that has been left out of this step toward inclusivity.

I started to realise I was asexual around the time my peers around me realised they weren’t. Puberty kicked in, hormones went flying, kids stopped wanting to just play together and started fancying each other instead. They became a lot more curious about their sexuality and wanted to express it.

But I just wasn’t feeling it; I didn’t get all the drama. In fact, I even switched to an all-girls’ school because I thought, without boys, everyone would stop caring so much about sexandrelationships, and would just chill out. Yeah, I was very wrong.

In secondary school, it became even more obvious that I wasn’t feeling the same as the other teenagers – and they didn’t like it. They started quizzing me constantly about why I felt the way I did.

“Are you gay?”, “Is it a mental disorder?”, “Is there something wrong with your genitals?”, “Did you get molested as a child?”, “You’re probably just underdeveloped or a late bloomer?”, “Surely you’re just being too picky?”, “You must just be unlovable or unattractive to everyone?”

My physical and mental health was up for debate. But back then, at 15, I didn’t really have an answer. That’s when one of my classmates said, “Maybe you’re asexual or something.” I’d only really heard the word 'asexual’ used about organisms in biology class, not in the context of human sexuality.

So I Googled it and thought it sounded like me, but at the time, there was so much disinformation online that I wasn’t 100% sure. Besides, when everybody keeps telling you there must be something wrong with you, after a while, you start to wonder if they’re right. You begin to doubt yourself, to question your own life experiences, your own thoughts and identity.

It wasn’t until I started talking to other asexual people – strangers online whose experiences, finally, reflected my own – that I started to realise I wasn’t alone. This wasn’t some sort of grand turning point though. It would take a number of years to stop doubting myself and my identity; a natural consequence of being pathologised and gaslighted for so long. Through launching my activism career to raise awareness of asexuality and aromanticism on my platform, I met an entire population of people like me. I attended the UK Asexuality Conference in 2018 and was greeted by hundreds of people who showed me the true diversity of the ace community.

There are asexual people who, like me, experience little to no levels of sexual attraction, and have no sexual or romantic – that’s the 'aromantic’ part – desire towards other people. But I learnt that there are a lot of asexual people who still experience romantic attraction and vice versa. I know many married asexual people, and aromantic sexual people – I’m sure we all know someone who’s not really into dating or relationships, but still loves sex! I know people in our community who are parents, grandparents, husbands, wives, young, old, Black, white – and they are proud of who they are.

The problem is, those stereotypes and toxic misconceptions I heard as a 15-year-old from my classmates at school? I still hear them today. We live in a society obsessed with relationships; where to love and be loved by another person is not only the ultimate aspiration, but the expectation.

Until asexuality becomes part of public discourse and representation, we will continue to be misunderstood, told that there’s something wrong with us, overlooked in education and legislation, and medicalised (and medicated). Women like me will continue to be dismissed as unlovable, ugly, frigid and boring. This is especially true for Black women, who are so hypersexualised, that to be a Black asexual woman seems entirely contradictory to people.

But I live a perfectly happy and fulfilled life as a Black asexual, aromantic woman. I don’t need a partner to complete me – I’m complete just the way I am. That’s why I use my platform to fight against asexuality stigma, dispel myths and help empower the ace community.

For allies, as always, the first step to show your support is by educating yourself, and to start normalising asexuality by including it in your conversations. That way, conversations around sexuality will inevitably become more inclusive and comfortable for the ace community. Asexual people will – finally – begin to feel seen.

We deserve to be seen.

Yasmin is the co-founder of International Asexuality Day, taking place this year on 6th April. Found out more internationalasexualityday.org.

Follow Yasmin on InstagramandTwitter.

https://www.glamourmagazine.co.uk/article/asexuality-and-aromanticism

There is a phase in our lives where everyone seems asexual and almost everyone seems aromantic. It wasn’t until puberty kicked in that platonic relationships seemed to take a backseat. My peers stopped wanting to play together and started wanting to ‘date’ each other. That was when I started to realise that there was something different about me. I didn’t seem to be experiencing the same urges as those I was around. I chose to go to an all girls school in the hopes that – in the absence of boys – everyone would stop caring about sex and dating. It actually had the opposite effect. There was a sense of deprivation in the air and the heightened desire to project their sexuality onto anything and everything.

Therefore, my lack of interest became even more obvious, and it became a not-so-fun game to work out the source of what should be troubling me, but hadn’t been until that point. Having a sexual orientation isn’t just natural, it’s essential. It’s part of being a fully-functional human being. And to be romantically love and be loved by another is the ultimate goal. It’s part of being normal, which made me both abnormal and puzzling. When your asexual, people think there’s something wrong with your body. When you’re aromantic, they think there’s something wrong with your soul. Even for a teenage girl who internalised all of Disney Channel’s “be yourself” messages, it’s never nice to have people publicly debate your supposed physical and psychological flaws.

My nickname in school was “hollow and emotionless.” I was a joker with a decent amount of friends, but I was lacking something crucial, the kind of love that really mattered and the kind of lust that made life exciting…so I was practically Lord Voldemort with braids. I sat through the regular DIY sexuality tests, having my peers show me graphic sexual imagery, have very sexual conversations in my presence, and ask me inappropriately intimate questions to gauge how far gone I truly was. These tests lead to the development of theories, most centred around me having some kind of mental problem. After a while, you start to wonder if everyone knows something you don’t.

When they said that I must have been molested as a child and “broken” by the trauma, I wondered if I had somehow forgotten about sexual abuse that actually hadn’t happened. I looked at some of my own relatives with suspicion, the same people who would later ask me if I didn’t experience sexual attraction because I was a pedophile. It was suggested that I was “suffering” from my “issues” because I was socially anxious and insecure. The suggestion that my ‘issue’ was pathological stayed with me for a long time, but not as much as the widely accepted theory that I was mentally slow. Unfortunately, that one stuck. I was referred to as “stupid” and I started to believe that was the case. It would impact my experience in education for the next eight years, long after I realised that there was a word for what I was.

Asexual.

I first heard the word during one of the near-daily sexuality tests that I was subjected to. I was asked if I was gay, to which I said that I wasn’t interested in anybody like that – men or women. At fifteen, I was asked, “Maybe you’re asexual or something?” but it wasn’t quite a lightbulb moment. How could it be when I had never heard the word outside of biology class? After an evening of Google searching, I realised that there were many people with my exact same experience, complete strangers whose stories sounded so strangely similar to mine. I also stumbled across the word ‘aromantic,’ but at the time, I didn’t understand the need for it. “Wouldn’t all asexual people be aromantic? A romantic relationship without sex is just friendship with rules,” I thought.

Either way, my discoveries showed me that I wasn’t alone, but that only half helpful. I now had an identity that no one had heard of or understood. Most didn’t believe that being asexual or aromantic was a real thing, and I doubted it to. I had been taught to after years of armchair pathologisation. If asexuality was real, why did no one tell you that being sexually attracted to nobody was an option? What if it was just an internet identity made up to comfort people with all of the issues that had been attributed to me? I didn’t have to go far down the rabbit hole to realise that asexuality, like many non-heteronormative identities, had been medicalised. What I had experienced as just the tip of the iceberg. As someone who hadn’t been prescribed drugs I didn’t need or subjected to unnecessary hormone tests, I was one of the lucky ones.

My activism would be my gateway to the community. Despite being the ugly friend at school, I ended up becoming a model while in university. I decided to use the platform I had gained through my career to raise awareness for asexuality and aromanticism. It gave me the opportunity to encounter a range of asexual and aromantic offline, it was then that I learned the significance of having an aromantic identity. There are many asexual people who still feel romantic attraction, as well as aromantic people who still feel sexual attraction. They have their own range of experiences, their own culture, their own flag, and like the asexual community, I was relieved to see that they are just normal people. These intersecting communities are not stereotypes. They weren’t just thirteen year old, pink haired kids making up identities on Tumblr to feel special. They were parents, lawyers, academics, husbands, girlfriends, artists, black, white, young, old, with differing feelings towards the many complex elements of sexuality and intimacy. Most importantly, they were happy.

I am proud to be part of both, and I know that while being asexual and aromantic, I am a complete person and I can live a perfectly fulfilling life. Since meeting members of my communities, I’ve become more open about my identities in real life, and a reaction I’m often met with is sympathy. “You must feel like you’re missing out,” “I can’t imagine being like that,” “It must be hard for your family,” “Do you worry no one will want you?” “How do you handle being so lonely?” “You’re so brave and strong,” “What will you do with your life now?” Even in 2021, a woman who isn’t romantically loved or sexually desired by their “special someone” is perceived as being afflicted with some kind of life-limiting condition.

Asexuality doesn’t make undesirable or unable to desire others. It is a unique experience of sexuality, not a deprivation from it. Even if it was, there is so much more to life than what turns us on and what we do about it. Romantic love is just one form of love, neither superior nor inferior to any other. Being aromantic doesn’t mean that you can’t love or be loved, it does not mean you are void of other emotions or capabilities. I am not lonely with my friends, family, co-workers and supporters. I feel confident not when someone wants to date me but when I meet my goals and form worthwhile connections with others. My success isn’t determined by whether someone will want to marry me someday. What we want out of life is our decision alone, our sources of happiness should not be defined by our ever-changing, culturally relative social standards. The love of a romantic partner won’t complete me because I was born complete. Feeling sexual attraction to others won’t liberate me because my liberation is not dependent on other people.

Valentine’s Day is on the horizon. It’s an occasion that amps up the focus on (and the pressure to achieve) a very specific type of love and sexual expression, one that is actually alienating for people inside and outside of the asexual community. During a pandemic where many relationships have been strained, tested, formed or distanced, it’s important to keep the diversity of romantic and sexual feelings in mind. Many expect me to feel annoyed or lonely during this time of year, but I actually feel empowered and excited by the way sex, romance and love are discussed more deeply around this time. These conversations are constantly expanding to become more inclusive for everyone, and that’s what we need to see all year round.

https://www.vogue.co.uk/arts-and-lifestyle/article/asexuality-and-aromanticism

The Future: Yasmin Benoit in Attitude Magazine (Feb 2021)

We are the future! I’m honoured to be included in Attitude Magazine’s first ever #Attitude101 influential figure list as a trailblazer in their The Future (25 & Under) category!

After such a crazy year, it’s amazing to have my work recognised like this. To be mentioned on the same list as incredibly accomplished people like Pete Buttigieg, Russell T Davies, Elliot Pages, Edward Ennifel OBE and so many others is so humbling. This is the kind of energy we’re going to carry into 2021 - asexual and aromantic inclusion in the LGBTQ+ community and beyond!

Thank you all for your continued support throughout this wild ride. You can find me in their February 2021 issue, which is available now on newstands and to buy online! I’ll be heading out to get my copy soon.

Happy New Year! ✨