#william faulkner

Noun

[meyl-struhm ]

1. a large, powerful, or violent whirlpool.

2. a restless, disordered, or tumultuous state of affairs:

the maelstrom of early morning traffic.

3.(initial capital letter) a famous hazardous whirlpool off the NW coast of Norway.

Origin:

Maelstrom comes from an early Dutch proper noun that is a combination of the verb malen (“to grind”) and the noun stroom (“stream”). The original Maelstrom, now known as the Moskstraumen, is a channel located off the northwest coast of Norway that has dangerous tidal currents and has been popularized among English speakers by writers such as Edgar Allan Poe and Jules Verne (whose writing was widely translated from French) in stories exaggerating the Maelstrom’s tempestuousness and transforming it into a whirling vortex. Maelstrom entered English in the 16th century and was soon applied more generally in reference to any powerful whirlpool. By the mid-19th century, it was being applied figuratively to things or situations resembling such maelstroms in turbulence or confusion.

“There is that might-have-been which is the single rock we cling to above the maelstrom of unbearable reality.”

- William Faulkner

by William Faulkner

What’s it about?

Like all Great American Novels, it’s about the death of the American Dream.

That doesn’t tell me much.

In particular, it’s about the collapse of the Southern Way of Life, a largely fictional reconstruction of what life was like for white people in the southern states of America (under slavery, which is never mentioned/realised by the kind of people who wave Confederate flags unironically).

So it’s a political book?

No. That was just me venting. Sorry. It’s actually the collapse of the South using the microcosm of a single family. We get to watch the very strange relationships they’ve built up among themselves slowly fall apart. There’s a bit of implied brother / sister stuff, but if you’ve read Game of Thrones and you still think the sibling incest overtones are too much, you should present yourself to the relevant authorities at first light.

I’ve started it, but it’s all gibberish.

Right. The first seventy pages or so are written in a style called “stream of consciousness”, the primary example of which is Ulysses by James Joyce. The narrative style tones down to something more comprehensible after that, so stick with it. By the fourth section, you’ll start to realise you remembered more than you thought.

What should I say to make people think I’ve read it?

“A genuinely brilliant attempt to model how human thought processes work and how our memories sometimes control who we are.”

What should I avoid saying when trying to convince people I’ve read it?

“These are the nonsensical ravings of a lunatic.”

Should I actually read it?

Yes. You’ll never come across a book quite like this. It primes you for the final emotional punch early on and you don’t even know it’s happening. Just keep reading.

Perhaps they were right in putting love into books.

Perhaps it could not live anywhere else.

-William Faulkner

— Значит, ты доверилась не мне, поверила не в меня, а в любовь. — Она посмотрела на него. — Значит, дело не во мне. На моем месте мог оказаться любой.

— Да, в любовь. Говорят, что любовь между двумя людьми умирает сама по себе. Это неверно. Она не умирает. Она просто покидает их, уходит от них, если они недостаточно хороши, недостойны ее. Она не умирает, умирает тот, кто теряет ее. Это похоже на океан: если ты плох, если ты начинаешь пускать в него ветры, он выблевывает тебя куда-нибудь умирать. Человек все равно умирает, но я бы предпочла умереть в океане, чем быть вышвырнутой на узкую полоску мертвого берега, где меня иссушит солнце, превратит в маленький вонючий комочек без всякого имени, единственной эпитафией которому станет «Оно было».

I HATE how tumblr brings up your old tags as you’re typing a new tag because I really don’t!! Want to remember!!! Some of the things I’ve said on this godforsaken site!!!!

tag this post with your first result you get when you type will

Post link

Between grief and nothing, I will take grief.

William Faulkner

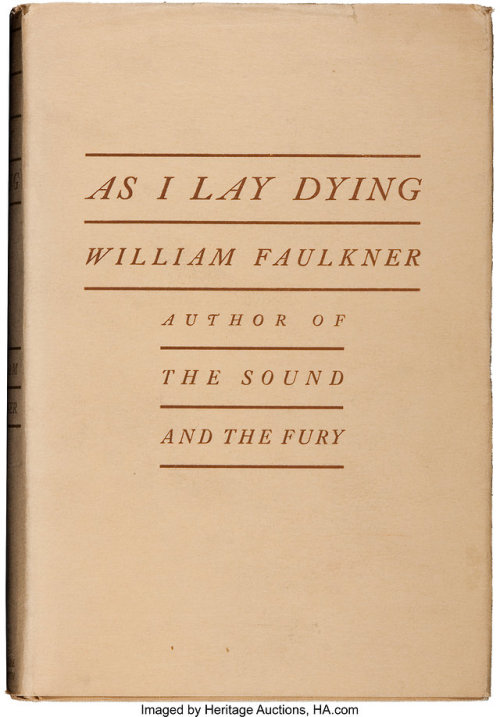

William Faulkner, As I Lay Dying (1930)

In a strange room you must empty yourself for sleep. And before you are emptied for sleep, what are you. And when you are emptied for sleep, you are not. And when you are filled with sleep, you never were. I dont know what I am. I dont know if I am or not. […] And then I must be, or I could not empty myself for sleep in a strange room. And so if I am not emptied yet, I am is.

How often have I lain beneath rain on a strange roof, thinking of home.

Post link

Faulkner and Wittgenstein on the privacy of experience

(Pictured: Addie Bundren [Beth Grant] in James Franco’s 2013 adaptionofAs I Lay Dying. [Millennium Films])

William Faulkner (1897–1962) was a Nobel laureate who authored classic novels The Sound and the Fury(1929) and As I Lay Dying (1930) as well as many more. Here we explain how his characters in As I Lay Dying broach the struggle of expressing private experience, a struggle also described in the works of philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein.

A poor and rural family slowly traverse the Mississippi countryside to bury their deceased wife and mother, Addie Bundren, miles away in town, meeting tribulations along the way.

In one chapter—from beyond the grave or in a flashback—Addie narrates her inability to express her private experiences of being a teacher, a wife, and a mother (ironically, using language). Whereas in action she is able to feel her own presence—for example, by physically punishing her students—she believes words to be like ‘spiders dangling by their mouths from a beam, swinging and twisting and never touching’.

‘That was when I learned that words are no good; that words don’t ever fit even what they are trying to say at. When [my son] was born I knew that motherhood was invented by someone who had to have a word for it because the ones that had the children didn’t care whether there was a word for it or not. I knew that fear was invented by someone that had never had the fear; pride, who never had the pride.’

Words, she expands, are ‘just a shape to fill a lack; that when the right time came, you wouldn’t need a word for that any more than for pride or fear’ or love.

This all should immediately remind us of the views of Wittgenstein, who argued that inner mental states cannot be known; that wouldn’t make sense, for they are incommunicable. There is a divide between mind and world, which is what Addie alludes to.

Nonetheless, in Philosophical Investigations (published posthumously in 1953) Wittgenstein writes that meaning can be conveyed, practically, if the rules of a public language game are followed, for language is a social practice.

Does this mean we shouldn’t try to bridge said gap? Here we can draw on Stanley Cavell’s distinction between (1) knowledge and (2) acknowledgement: (1) there is a limited capacity of language to capture truths about the world and others’ experiences; (2) however, through sympathy we can acknowledge in others what we cannot experience ourselves. Too stark a divide unduly abolishes our obligations to the world and that which we value.

Indeed, Addie is able to gain acknowledgement by forcing pain in others—her husband; her students—not by using words but by exacting revenge and violence. Of the students, she says:

‘I would look forward to the times when they faulted, so I could whip them. When the switch fell I could feel it upon my flesh […] and I would think with each blow of the switch: Now you are aware of me! Now I am something in your secret and selfish life.’

Addie is sceptical of language’s faithfulness to worlds privately and uniquely inhabited. But she seeks acknowledgement. Her daughter, Dewey Dell, unlike her mother, fears even acknowledgement: the obtaining of worldly connections is a violation of her aloneness. Of the recognisable changes to her body during an unwanted pregnancy, she says: ‘The process of coming unalone is terrible’.

The Bundrens are isolated farmers who live in simple fashion. Their thoughts are incoherent and stream-like. Faulkner and Wittgenstein both show that the private worlds from which we feel and sense are inaccessible to language. This limit is felt particularly strongly by the Bundrens, alienated countryfolk whose linguistic capacities and abilities to follow language games are already impoverished.

⁂

Words are signifiers. Your name, for example, signifies you, the signified. But perhaps saying is a cheap substitute for doing. Addie Bundren thought so.

‘Sometimes I would lie by him [my husband, Anse] in the dark, hearing the land that was now of my blood and flesh, and I would think: Anse. Why Anse? Why are you Anse. I would think about his name until after a while I could see the word as a shape, a vessel, and I would watch him liquefy and flow into it like cold molasses flowing out of the darkness into the vessel, until the jar stood full and motionless: a significant shape profoundly without life like an empty door frame; and then I would find that I had forgotten the name of the jar […]

‘I would think how words go straight up in a thin line, quick and harmless, and how terrible doing goes along the earth, clinging to it.’

Post link

![Movie Title #62The Tarnished Angels [USA 1957, Douglas Sirk] Movie Title #62The Tarnished Angels [USA 1957, Douglas Sirk]](https://64.media.tumblr.com/75903bf808de1150df0ec35e697bef08/tumblr_odk3ul0xls1trk2zco1_500.jpg)

![Faulkner and Wittgenstein on the privacy of experience(Pictured: Addie Bundren [Beth Grant] in James Faulkner and Wittgenstein on the privacy of experience(Pictured: Addie Bundren [Beth Grant] in James](https://64.media.tumblr.com/a3e77e51df6a393b3d6f1dfcef07faae/e6d137e19008395e-56/s500x750/c0371d7d5d4345963ffbdc5b607e7e7dfced4659.jpg)