#article

The 10 times ‘Braceface’ was too real for a kids show

source: Teletoon You might wanna buckle up for this one, because I’m about to dive into a show that got too real at numerous times. Think of an early 2000s teenage cartoon with ten times the drama, and you’ll get Braceface. Much like other tween series like As Told by Ginger, Braceface centers a awkward yet smart teenage girl who longs for popularity, with two best friends by her side. Oh and I…

Too dark for Disney? Behind the deleted and edited scenes of Lilo & Stitch

What exactly is “too much” for a young audience? How do we possibly figure out what could be too sensitive to viewers of a movie or television show? I guess there isn’t any particular test to measure just how many people would find a certain piece of media offensive or triggering. As a company, business or even an individual, it is essential to keep in mind whether your content could have aspects…

The 10 shocking times ‘Braceface’ was too real for a kids show

source: Teletoon You might wanna buckle up for this one, because I’m about to dive into a show that got too real at numerous times. Think of an early 2000s teenage cartoon with ten times the drama, and you’ll get Braceface. Much like other tween series like As Told by Ginger, Braceface centers a awkward yet smart teenage girl who longs for popularity, with two best friends by her side. Oh and I…

The 10 times ‘Braceface’ was too real for a kids show

source: Teletoon You might wanna buckle up for this one, because I’m about to dive into a show that got too real at numerous times. Think of an early 2000s teenage cartoon with ten times the drama, and you’ll get Braceface. Much like other tween series like As Told by Ginger, Braceface centers a awkward yet smart teenage girl who longs for popularity, with two best friends by her side. Oh and I…

»Don’t you think, its in your hands, to change bad things in good?«

My new drawing is finally done. Let me know what you’re thinking while looking at this. Thank you! xx

»An entire sea of water can’t sink a ship unless it gets inside the ship. Similarly, the negativity of the world can’t

put you down unless you allow it to get inside you.«

Toni Mahfud

Post link

« I keep a journal of quotes, lines from songs, poetry. Nothing is my original thought — but all of it struck me as meaningful when I wrote it down.

[…] From my early 20s, there are pages trying to convince myself that friendship, which I had, could be as valuable as romantic love, which I didn’t. (Andrew Sullivan: “If love is about the bliss of primal unfreedom, friendship is about the complicated enjoyment of human autonomy.”) […] Ultimately, when I was no longer so preoccupied with finding romantic love, my shift toward looking more closely at my other relationships is mirrored in my transcriptions: Vivian Gornick on her relationship with her mother; Durga Chew-Bose on the rapturous, fresh intimacy that I miss now.

[…] Thrumming beneath the pages is a shifting self-image. When I read them, I recognize the past me who saw herself in these quotes, but I don’t roll my eyes at her. With others’ words as intermediaries, the harsh light of hindsight softens. If keeping a journal would be a way to look in the mirror and make an honest appraisal of myself, keeping a commonplace book is more like looking at myself out of the corner of my eye.

It’s an admittedly different approach from my generation’s inclination toward full-frontal accountability. Daily diary apps and self-improvement podcasts and confessional Instagram stories evince a belief that to grow as a person you have to be entirely, unflinchingly forthcoming. But I couldn’t catalog my flaws without flinching. And I don’t think I need to. That’s part of the point of reading, I think: When I find myself too earnest, too impatient, too much, I can be in conversation with other minds instead. Keeping a commonplace book feels like a kinder way to grow, by wrestling with the articulations of others in the open as I hopefully adjust myself within. »

— Charley Locke, “Commonplace Books Are Like a Diary Without the Risk of Annoying Yourself”

« Foreigners follow American news stories like their own, listen to American pop music, and watch copious amounts of American television and film. […] Americans, too, stick to the U.S. The list of the 500 highest-grossing films of all time in the U.S., for example, doesn’t contain a single foreign film (Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon comes in at 505th, slightly higher than Bee Movie but about a hundred below Paul Blart: Mall Cop). […]

How did this happen? How did cultural globalization in the twentieth century travel along such a one-way path? And why is the U.S.—that globe-bestriding colossus with more than 700 overseas bases—so strangely isolated?

[…W]hen 600 or so journalists, media magnates, and diplomats arrived in Geneva in 1948 to draft the press freedom clauses for […] the U.N. Declaration of Human Rights […], definitional difficulties abounded. Between what the U.S. meant by “freedom of information” and what the rest of the world needed lay a vast expanse. For the American delegates, the question belonged to the higher plane of moral principle. But representatives of other states had more earthly concerns.

The war had tilted the planet’s communications infrastructure to America’s advantage. In the late 1940s, for example, the U.S. consumed 63% of the world’s newsprint supply; to put it more starkly, the country consumed as much newsprint in a single day as India did over the course of a year. A materials shortage would hamper newspaper production across much of the world into at least the 1950s. The war had also laid low foreign news agencies—Germany’s Wolff and France’s Havas had disappeared entirely—and not a single news agency called the global south home. At the same time, America’s Associated Press and United Press International both had plans for global expansion, leading The Economist to note wryly that the executive director of the AP emitted “a peculiar moral glow in finding that his idea of freedom coincides with his commercial advantage.”

Back in Geneva, delegates from the global south pointed out these immense inequalities. […] But the American delegates refused the idea that global inequality itself was a barrier to the flow of information across borders. Besides, they argued, redistributive measures violated the sanctity of the press. The U.S. was able to strong-arm its notion of press freedom—a hybrid combining the American Constitution’s First Amendment and a consumer right to receive information across borders—at the conference, but the U.N.’s efforts to define and ensure the freedom of information ended in a stalemate.

The failure to redistribute resources, the lack of multilateral investment in producing more balanced international flows of information, and the might of the American culture industry at the end of the war—all of this amounted to a guarantee of the American right to spread information and culture across the globe.

The postwar expansion of American news agencies, Hollywood studios, and rock and roll bore this out. […] Meanwhile, the State Department and the American film industry worked together to dismantle other countries’ quota walls for foreign films, a move that consolidated Hollywood’s already dominant position.

[…A]s the U.S. exported its culture in astonishing amounts, it imported very little. In other words, just as the U.S. took command as the planetary superpower, it remained surprisingly cut off from the rest of the world. A parochial empire, but with a global reach. [And] American culture[’s] inward-looking tendencies [precede] the 1940s.

The media ecosystem in particular, Lebovic writes, [already] constituted an “Americanist echo chamber.” Few of the films shown in American cinemas were foreign (largely a result of the Motion Picture Production Code, which the industry began imposing on itself in 1934; code authorities prudishly disapproved of the sexual mores of European films). Few television programs came from abroad […]. Few newspapers subscribed to foreign news agencies. Even fewer had foreign correspondents. And very few pages in those papers were devoted to foreign affairs. An echo chamber indeed, [… which] reduced the flow of information and culture from much of the rest of the world to a trickle. […]

Today is not the 1950s. [… But] America’s culture industry has not stopped its mercantilist pursuits. And Web 2.0 has corralled a lot of the world’s online activities onto the platforms of a handful of American companies. America’s geopolitical preeminence may slip away in the not-so-distant future, but it’s not clear if Americans will change the channel. »

— “How American Culture Ate the World”, a review of Sam Lebovic’s book A Righteous Smokescreen: Postwar America and the Politics of Cultural Globalization

« The products of mass culture have learned to speak a new language: the language of the occult. Come in, an app pleads, and listen to an algorithmically curated playlist of songs that “fit the vibe.” It’s hard, a marketing email laments, to build an organization filled with people whose “energies align.” […]

Once,vibe, mood, and energy were watchwords of the counterculture. Among hippies, dropouts, and other assorted voyagers in psychedelia, they were part of a private shorthand for sensations strongly felt but not so easily explained. Today, this vocabulary has diffused beyond any niche group.

Still, it is possible to identify a sort of vanguard. Perhaps the most dedicated speakers of the language of the occult today are millennial and Gen Z denizens of social media platforms. For them — forus— it has become received common sense that some days “the vibes” are simply off; that everything from a weird-looking cat to a cargo ship stuck in the Suez Canal is a potential object of identification, an occasion for remarking, “Same energy,” or more tersely, “Mood” — which is to say, “That’s me!” Tumblr, TikTok, and Instagram users assemble collections of images and clips intended to produce a distinct impression, an overall mood or vibe: forest clearing, tweed jacket, roaring fire, marble bust.

Unlike the “invisible energies” that were [back in the day] supposed to join us together as “citizens,” [the modern] conception of energy tries to give a form to […] apparently disparate things. Less a metaphor for collective life and more a heuristic for sorting through a bottomless pile of independently generated but centrally stored content. […] There is no satisfactory and readily available account of how the simple non-act of scrolling through one’s feed comes to feel so nebulously miserable. In the age of the platform, energy, once a figure of utopian collectivity and mystical omni-connection, becomes a tool for making the most of our helplessness […]: projecting visions of cosmic sympathies onto the black boxes that organize and administer so much of contemporary life. […]

[Similarly,]vibe is primarily about the spread and creep of diffuse feelings through shared space. Afforded what feels like perfect access to a dizzying number of other persons, what they report to be thinking and feeling at any given moment, we have little choice but to take this data in aggregate, not as an accumulation of individuals’ joy and suffering but as a series of impersonal, thrumming emotional ground tones. These tones are often unpleasant, if only in a vague, formless way.

A scan of social media returns far more talk of bad vibes than good. All summer, apparently “the vibes were off” in New York City. On the occasion of a mass shooting, a professional player of video games pronounces: “Fucked vibes.” Popular TikTok accounts like “vibes.you.crave” post montages of vibey images — train platforms, snowy darkness — and users reply to report how existentially hollow these videos make them feel. “I feel empty and satisfied at the same time,” writes one commenter. “These pics makes me feel empty and in a way i can’t explain,” confesses another. […]

For young users on these platforms, the transcendental fucked-up-ness of the world does not register as a crisis, but as a vibe — a low-hanging miasma of ambient bad feelings. To invoke a vibe is to try to make this atmosphere a little more understandable, to gain enough distance from it to start to describe it.

If naming a vibe is a way to register the encompassing badness of things, there is also a sense thatembracing a vibe might be a strategy for repairing this badness, or at least shutting it out. As good a catchphrase as any for this conviction is “no thoughts, just vibes.” […] It is a statement of only semi-ironic aspiration to return, as Freud put it long ago in his theorization of the death drive, to unthinking inorganic matter. […]

Even in its less extreme versions, “no thoughts, just vibes” is something like a mantra for depersonalization. Online, if it isn’t a selfie caption, the phrase often accompanies an image of a nature scene (sunset, dog in a meadow) or else a scene of debauchery (disco ball, handle of vodka). Drugs, mystical philosophy, the sublime in nature: pick your poison; all techniques of vibing are methods for getting momentary relief from the burdens of personhood, for relaxing the boundaries of the self in the name of finding a slightly less painful way of living in the world. There is a […] distance between these vibes and those of the midcentury counterculture. “No thoughts, just vibes” finds vibe shedding its sociability and its aspiration for extended sensation. It abandons shared feelings for private unfeeling. »

— Mitch Therieau, “Vibe, Mood, Energy | Or, Bust-Time Reenchantment”

« [A] revolution in knowledge is revealing the enormous richness and cognitive complexity of animal lives, which prominently include intricate social groups, emotional responses, and even cultural learning. We share this fragile planet with other sentient animals, whose efforts to live and flourish are thwarted in countless ways by human negligence and obtuseness. […] If injustice involves wrongfully thwarted striving—and I think that’s a pretty good summary of the basic intuitive idea of injustice—we cause immense injustice every day, and injustice cries out for accountability and remediation.

But to think clearly about our responsibility, we need to understand these animals as accurately as we can: what they are striving for, what capacities and responses they have as they try to flourish. […We] also need an ethical theory to direct our efforts in policy and law. [The Utilitarian] theory holds that pain is the one bad thing and pleasure the one good thing. [It] looks like a beginning: if we were only to get rid of the torture to which we subject animals daily—through the manifold harms of the meat industry, through habitat destruction, through lethal pollution—we would improve animal lives considerably.

[But Utilitarianism] lacks curiosity about the diversity of goals each animal life pursues. An elephant in a zoo enclosure, or an orca in a pen, might possibly lack pain if well cared for, but she would still lack free movement over a large terrain and the company of a large social group. […] People who care about animals have therefore increasingly turned to a theory known as the Capabilities Approach (CA), [in which] the central question is “What is this creature actually able to do and to be?”

For each species, it must identify the most significant activities and a minimum threshold beneath which we should judge an animal’s life to be unjustly thwarted. It must also allow plenty of room for the individual choices of different members of the species. And then we must propose strategies for achieving that threshold in law and policy. […]

A favorite case of mine is Natural Resources Defense Councilv.Pritzker(2016), in which the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals invalidated the US Navy’s sonar program on the grounds that it violated the Marine Mammal Protection Act by impeding several characteristic marine mammal activities […]. This novel interpretation of the statute is exactly what the CA would recommend. Even though the sonar did not cause physical pain, the fact that the whales were unable to live their characteristic lives was sufficient to make it a violation of the statutory requirement to avoid “adverse impact” on marine mammal species.

[…] Achieving even minimal justice for animals seems a distant dream in our world of casual slaughter and ubiquitous habitat destruction. One might think that Utilitarianism presents a somewhat more manageable goal: Let’s just not torture them so much. But we humans are not satisfied with non-torture. We seek flourishing: free movement, free communication, rich interactions with others of our species (and other species too). Why should we suppose that whales, dolphins, apes, elephants, parrots, and so many other animals seek anything less? If we do suppose that, it is either culpable ignorance, given the knowledge now so readily available, or a self-serving refusal to take responsibility, in a world where we hold all the power. »

— Martha Nussbaum, “What We Owe Our Fellow Animals” in The New York Review of Books

“If Democrats win the presidency and a senate majority next week they will have a window of opportunity not just to legislate Democratic policy priorities but far more importantly to reopen the clogged channels of democratic process and action. That requires expanding the Court with at least four new Justices as well as expanding the federal judiciary as a whole – quite apart from composition the federal judiciary simply has too few judges at present.. It requires ending the Senate filibuster. It means adding Washington DC and Puerto Rico as new states of the Union. It means a lot else too. You can mix and match specific approaches. But nothing is possible without unclogging the arteries of democracy itself. Without an expanded Court we will see years and decades into the future in which the Court manufactures increasingly ornate and absurd ‘originalist’ reasonings that find quite disinterestedly that basically all Democratic policy initiatives are barred by the federal Constitution.”

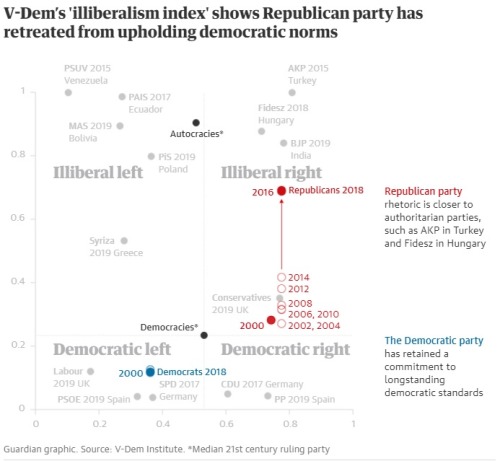

Republicans closely resemble autocratic parties in Hungary and Turkey – study

Swedish university finds ‘dramatic shift’ in GOP under Trump, shunning democratic norms and encouraging violence

The Republican party has become dramatically more illiberal in the past two decades and now more closely resembles ruling parties in autocratic societies than its former centre-right equivalents in Europe, according to a new international study.

In a significant shift since 2000, the GOP has taken to demonising and encouraging violence against its opponents, adopting attitudes and tactics comparable to ruling nationalist parties in Hungary, India, Poland and Turkey.

The shift has both led to and been driven by the rise of Donald Trump.

Post link

maritsa-met-deactivated20210227:

Why This Restaurant Critic Isn’t Dining Out Right Now

“I have no doubt that smart people have carried out rigorous cost-benefit studies about keeping businesses open, arguing that at some point the social ills of a stagnant economy will wreak more havoc than the virus. Thing is, my argument isn’t a macro one for policymakers — who should pay workers so they can stay at home — it’s a micro one for consumers. For me, the low risk of sending a single uninsured waiter to an ICU bed, someone who isn’t really there by choice, in exchange for the pitcher of frozen margaritas you happen to be craving in the late afternoon, is a morally indefensible transaction.”

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-17829665

Over-consumption in rich countries and rapid population growth in the poorest both need to be tackled to put society on a sustainable path, a report says.

https://experiencelife.com/article/the-power-of-kindness/

Treating other people well isn’t just good for your karma. It’s good for your health and vitality, too.

Can the spaces in which we live, work, and recover from illness have an impact on healing and well-being?

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-32272817

An example of uk taxpayers subsidising private companies, by almost £11bn per annum".

http://www.motherjones.com/environment/2010/09/bp-ocean-cover-up

BP and the government say the spill is fast disappearing—but dramatic new science reveals that its worst effects may be yet to come.