#inspiraton

winter21

(Note: The terms “Black” and “African” are used interchangeably in this piece for contextualisation purposes.)

In 2001, Obrafour-arguably the most popular rapper in Ghana then- released his second album, Asem Sebe. On this album was the very popular love song, Odo. On Odo, Obrafour was basically professing his profound love for a certain Yaayaa Serwaa- a black woman, undoubtedly. (I would say ‘arguably’, but the video clarifies things.) In 2015, Sarkodiereleased his fourth album, Mary, and one of the numerous love songs on this album was ‘Always on my Mind’ (which incidentally featured Obrafour) and on it, Sark too was expressing his deep love for a black woman named Abena Amponsah. These two songs have a very curious and interesting thing in common: the rappers referring to these (black) love interests of theirs as white people, as a form of extollation and as terms of endearment- so we had Obrafour calling Yaayaa his 'white person’-mi broni, and Sarkodie calling Abena a 'black-white person’- tuntum broni.

In attempting to make a case for this very worrying situation, someone once responded to these observations saying something like, “perhaps, they’re only using the (o)broni term figuratively,” and i retorted, “that is exactly the problem.”

That whiteness has to be called upon to validate the beauty of a black woman. That whiteness has to be the standard, the default, the epitome when we’re talking about beauty and admiration. That a beautiful black woman can’t be just that -a beautiful black woman- without being referred to as a ’(black)-white’ person.

The fact of the matter is that this most unfortunate phenomenon is deeply rooted in colourism, and much deeper in the colonial experience. Simply, it is the reflection of a colonial mentality to have Africans feel the need to use phrases such as “mi broni” and “tuntum broni” to extol their love interests, who’re obviously African. After all, wasn’t it during the colonial experience that we were taught that everything 'white’ was aspirational, admirable, to be desired, and everything 'black’ on the other hand, disdainful, repulsive and to be abhorred?

This colourist “broni” business is of course, not limited to rap-in fact, it is much more prevalent in highlife music. It is not even limited to the music scene, but actually spread across our whole society. (Isn’t our music generally reflective of our society?) But for the purposes of this blog, the focus will be on rap/hip hop music in Ghana.

In decrying this mentality that breeds acts such as skin bleaching, most of our rappers, in their token 'conscious’ songs, often miss the mark.

In an industry whose (biggest) voices still use such anti-black(skin) terms such as tuntum broni, in an industry where we’re most likely to have have light skinned women featuring in music videos, where musicians feel the need to brag about the fact that the woman they dating is biracial, in an industry that basically suggests that 'the lighter, the better’-and therefore reinforces colourist ideals, you do not go about barking at people who bleach their skins. However well-intentioned these efforts may be, there is nothing conscious about attacking people who in this case, bleach their skins. A deeper look at it though, would reveal something ahistorical and hypocritical, and everything unconscious, about it all.

If artistes feel the need to make socially conscious and progressive songs (which is a very laudable thing), it is imperative that they educate themselves and also attack, instead of victims, the underlying ideas or structures that lead to whatever malaise within society they’re disgusted at. Unconsciously being part of a problem you cry against, is not cool. Neither is victim blaming.

In ‘Anthills of The Savannah,’ the late Chinua Achebe wrote a wonderful proverb. It says that “if you want to get to the root of murder, you have to look for the blacksmith who made the matchet.”

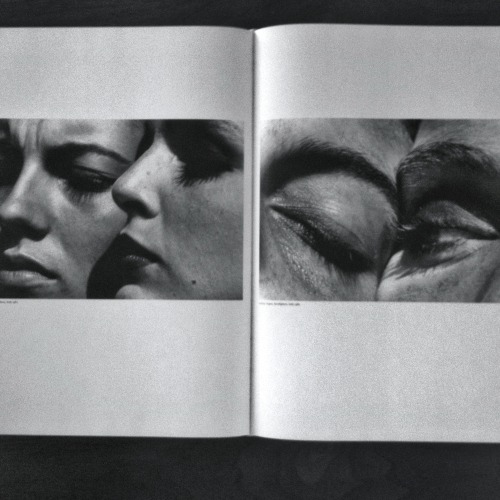

(Note: the last two photos are stills from this brilliant short film that explores colourism. Highly recommended.)

“And there are loners in rural communities who, at the equinox, are said to don new garments and stroll down to the cities, where great beasts await them, fat and docile.”