All strangulation of women is serious – and it’s time for the law to step up

Jamie Read, 31, attacked his girlfriend so ferociously, she thought she was going to die. He had followed her home after drinking in a pub. In court last year, Ramsay Quaife, prosecuting, said: “All of a sudden, he grabbed her throat and squeezed her hard. The victim was barely able to breathe… She saw him take six steps back before lunging at her and kicking her in the face with the sole of his trainer. He repeated this twice more.”

Read admitted assault occasioning actual bodily harm. The judge, Recorder John Trevaskis, said Read wouldn’t receive rehabilitative help in prison and gave him a 16-month jail term suspended for two years. Read walked free from court.

Next month, on 7 June, as part of the Domestic Abuse Act (2021), non-fatal strangulation (NFS) and suffocation becomes a free-standing offence, punishable by up to five years in prison in England and Wales. Campaigners including the Centre for Women’s Justice (CWJ) and We Can’t Consent To This – who challenged the defence where the perpetrator claims it happened as part of “rough sex gone wrong” – have long argued that NFS, if prosecuted at all, was frequently charged as common assault, receiving a sentence of a few months.

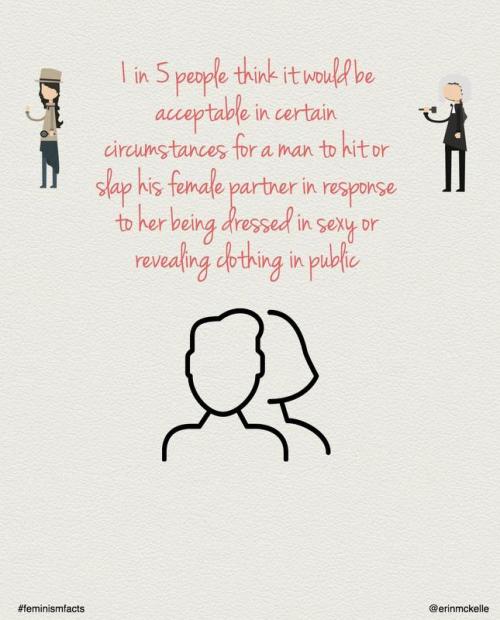

An estimated 20,000 strangulations a year are reported to women’s charities. “The vast majority are a way of exerting power, fear and control – but not fatal,” says CWJ’s Nogah Ofer. Prosecution is also impeded because it is often treated as a private matter, normalised by the increasing use of pornography. Yet NFS increases the odds of a woman being killed by a staggering seven times.

According to the Femicide Census, established by Karen Ingala Smith and Clarrie O’Callaghan, with whom the Observer has collaborated in a year-long campaign to better tackle femicide and violence against women and girls (VAWG), a woman is killed by strangulation every two weeks.

“The Femicide Census has consistently found that strangulation is the second most common method after stabbing that men use to kill women,” says O’Callaghan. “It’s long overdue that the criminal justice system catches up.”

In 2021, Anthony Williams, 70, “choked the living daylights” out of his wife, Ruth, 67. He received a five-year sentence after pleading guilty to manslaughter by reason of diminished responsibility. The new NFS offence is a vital opportunity to put a brake on coercion, control, intimidation, violence and killing – all of which statistically impact on women far more than men.

However, while senior judges and the judicial colleges are in discussions with the Ministry of Justice, nationwide training for police, health workers and all those engaged in bringing a perpetrator to trial, so far, appears non-existent. “Women’s lives are at stake. The government should be seizing the initiative and ensuring that everyone involved is trained,” says Julia Drown, patron of the charity Advocacy After Fatal Domestic Abuse (AAFDA), and a member of small group of experts who have been lobbying for accelerated action.

Last year, Sam Pybus, 32, pleaded guilty to manslaughter after strangling Sophie Moss, 33, during what he alleged was consensual sex. He was jailed for four years and eight months – a sentence that triggered a public outcry but was upheld by the appeal court. A pathologist’s report found Moss’s injuries “do not suggest a very prolonged or very forceful strangulation”. Strangulation does not need to be prolonged or forceful to cause serious long-term damage.

Dr Catherine White is the foremost expert and researcher in strangulation in the UK. She is scathing about the lack of progress. The voluntary expert group of which she and Drown are a part has struggled for months to raise £7,000 to pay for two excellent half days of free training in NFS. Finally, NHS England provided the funds.

“Hopefully, we can ignite a fire in the belly for more training. But why are we volunteers doing this?” White says. “The Ministry of Justice should be knocking on my door, asking for training. The government says it is spending millions on VAWG but, when you look at the scale of the challenge, it’s peanuts.

“No one seems to be in overall control, driving forward a co-ordinated response. It feels like re-arranging deck chairs on the Titanic. The impact of strangulation, control and sexual violence is huge, yet the societal and government response is so lacking.”

Last year, White and colleagues published I Thought He Was Going to Kill Me, a three-year study of 204 adult cases of NFS as part of a sexual assault. Some 96.6% of the victims were female. In 27% of the cases, the woman had been strangled before by the same perpetrator. Over one in six had been strangled to the point where they lost consciousness.

It takes skill and training, often not found in GPs’ surgeries to detect the signs. One American study reported that “NFS might well be the equivalent of waterboarding – both leave few marks; both can be used repeatedly with impunity”.

White’s study reported that a male handshake has 80-100lbs per square inch (psi) of pressure. It takes 20psi to open a fizzy drink can. It takes only 4psi to occlude a jugular vein.

Strangulation is external pressure to the neck that cuts off air, or the flow of blood to the brain (choking is different, caused by an internal obstruction to the airwaves). For those who survive, symptoms include strokes, depression, memory loss, seizures, motor and speech disorders and paralysis. The connection of these symptoms to NFS is often not recognised.

White’s commitment to properly tackling NFS was triggered by taking a course at the Training Institute on Strangulation Prevention, Texas, co-founded in 2011 by lawyers Gael Strack and Casey Gwinn. The institute now trains thousands of frontline workers every year across the US.

A medical assessment, vitally, has to include imaging (MRI and CT scan) and forensic documentation of internal and external injuries. This approach has helped the San Diego domestic violence homicide rate to drop by 90% since the 1980s.“Strangulation is much more common than we realised – but also so much more serious then we ever gave it credit for,” says trainer Cat Otway.

Forensic physician Dr Helena Thornton has worked at St Mary’s Sexual Assault and Referral Centre, Manchester, with White for 27 years and is registrar of the faculty of Forensic and Legal Medicine. The General Medical Council refuses to allow forensic and legal medicine to become a specialisation so, incredibly, there are no national guidelines on training, qualifications and exams. In addition, senior forensic clinicians are retiring and not being replaced – so who will give evidence in court?

“St Mary’s is commissioned by police and the NHS but, in a lot of areas, the service has been outsourced for the lowest price, as cheap as possible,” Thornton says. “In some parts of the country, you might see someone who has received only three days’ forensic training. The faculty sets out what to expect from good treatment.

“When I see a patient, questions have to be asked, such as did you black out? When you came round, had you wet or pooed yourself? If you lose control of your bowel, that isn’t fear. It means you are seconds away from death.

“It’s embarrassing so a woman is unlikely to volunteer that information. If you haven’t been properly trained, you’re not capturing the evidence.”

Alarmingly, if you have been strangled but not sexually assaulted, it will be extremely difficult to find the level of examination required. White would like to see a branch of Strack’s institute in the UK, but that, too, has proved a struggle. “Everyone thinks it’s a good idea but, like training, no one seems to have a budget. I’ve seen statements where it’s just said, ‘red mark on neck’. What the heck is that – a felt-tip pen? A bruise?

“That lack of information influences whether the police and the Crown Prosecution Service decide to continue with the case. When you see the unfairness of the system for patients, that’s what gives me the energy to keep on fighting.”

Over the past two years, a national conversation about VAWG has been prompted by lockdowns, rising rates of domestic abuse, the exposed criminality of some police, and the shocking deaths of Sarah Everard, Bibaa Henry, Nicole Smallman and Sabina Nessa, among many others. Still, as O’Callaghan and Ingala Smith have argued for years, little attention is paid to the misogyny that is VAWG’s root cause – and to prevention.

The three aims of the Observer’s End Femicide campaign, now concluding, are: name it (government is reluctant to use the gendered word “femicide”, a killing of a woman by a man). Secondly, know it, for example, by improving data on racially minoritised women; and thirdly, stop it.

The government has a number of initiatives, including a domestic abuse plan and a VAWG strategy, while investing small pots of money, for instance, in police training (£3.3m). However, weighed against the estimated cost of domestic abuse alone, £66bn a year, and the plummeting rates of conviction – 90% of cases of domestic abuse brought to the police in 2020 did not end in a charge or summons – so much more is required.

“It feels as if government is only scratching the surface of the transformation we need,” says Andrea Simon, director of the End Violence Against Women (EVAW) Coalition, representing over 120 women’s specialist services, activists and survivors. “Who is holding all these strains of work together? Who is accountable when policies fail?

“The hypocrisy of the government is that in the Queen’s speech there was a raft of alarming legislation that directly attacks women’s and survivors’ rights, such as scrapping the Human Rights Act, an essential tool in challenging failures by the state to protect women and girls.”

On 8 June, it’s the 10th anniversary of the government’s signing of the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence, known as the Istanbul Convention (IC). The IC’s articles cover issues such as high-quality holistic services and appropriate funding and support for victims, overseen by a monitoring group. Once ratified, a government is legally bound to comply with the review process. The government has announced it will ratify in July but not yet include women with insecure immigrant status who have no recourse to public funds. (A pilot study is examining the experiences of migrant women.)

Hannana Siddiqui of Southall Black Sisters says she is “extremely concerned” about this two-tier system. “All women have a human right to protection from abuse.”

“While this reservation stands,” says Lisa Gormley who helped to draw up the IC, “women’s rights’ advocates will continue to call for justice and safety for all women and girls without discrimination, without limitations.”

“The convention is the gold standard in how you prevent and tackle VAWG,” Simon says. “It’s vital that there aren’t gaps in support. It’s a fundamental human right for all women to feel safe and free.”