#middle english

Noun

[ ih-fyoo-zhuhn ]

1. the act of effusing or pouring forth.

2. something that is effused.

3. an unrestrained expression, as of feelings:poetic effusions.

4.Pathology.

a. the escape of a fluid from its natural vessels into a body cavity.

b. the fluid that escapes.

5.Physics. the flow of a gas through a small orifice at such density that the mean distance between the molecules is large compared with the diameter of the orifice.

Origin:

1350–1400; Middle English (<Anglo-French ) <Latin effūsiōn- (stem of effūsiō), equivalent to ef-ef-+fūsion-fusion

“There is an intensity and effusion of spirit in them, in which his own more studied compositions are somewhat wanting.”

- CHARLES J. ABBEY AND JOHN H. OVERTON, THE ENGLISH CHURCH IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

Verb (used with object)

[ flout ]

1. to treat with disdain, scorn, or contempt; scoff at; mock:to flout the rules of propriety.

Verb (used without object)

2. to show disdain, scorn, or contempt; scoff, mock, or gibe (often followed by at).

Noun

3. a disdainful, scornful, or contemptuous remark or act; insult;gibe.

Origin:

First recorded in 1350–1400; Middle English flouten “to play the flute” (see flute); compare Dutch fluiten “to play the flute, talk smoothly, soothe, blandish, impose upon, jeer”

“Is it a safe thing, think you, Sir Count, to jest with a princess in her own land and then come back to flout her for it?”

- S(AMUEL) R(UTHERFORD) CROCKETT, JOAN OF THE SWORD HAND

Noun

[ weyf ]

1. a person, especially a child, who has no home or friends.

2. something found, especially a stray animal, whose owner is not known.

3. a very thin, often small person, usually a young woman.

4. a stray item or article:to gather waifs of gossip.

5. Nautical. waft (def. 8).

Origin:

First recorded in 1350–1400; Middle English, from Anglo-French, originally “lost, stray (animal), unclaimed (property)” (compare Old French guaif “stray beast”), from Scandinavian; compare Old Norse veif “movement to and fro, something waving, flag”; see waive

“Ann is an opera singer, fragile and captivating onstage, somewhere between waif and warrior.”

- ANNETTE IS GORGEOUS TO LOOK AT BUT ALL THE WRONG KINDS OF WEIRD|STEPHANIE ZACHAREK|AUGUST 6, 2021|TIME

Adjective

[ ad-uh-man-teen, -tin, -tahyn ]

1. utterly unyielding or firm in attitude or opinion.

2. too hard to cut, break, or pierce.

3. like a diamond in luster.

Origin:

1200–1250; Middle English <Latin adamantinus<Greek adamántinos. See adamant,-ine1

“Each bound to the other, through all the vicissitudes of life, in adamantine bonds of love and admiration!”

- Various, Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 71, No. 436, February 1852

Adjective

[lee-uh-nahyn ]

1. of or relating to the lion:

We breathlessly watched the pride, in its leonine majesty, as it moved across the veldt.

2. resembling or suggestive of a lion:

the conductor’s wild, leonine hair.

3. (usually initial capital letter) of or relating to Leo, especially Leo IV or Leo XIII.

Origin:

First recorded in 1350–1400; Middle English leonyn, from Latin leōnīnus “lionlike,” equivalent to leōn- (stem of leō) + -īnus; see origin at lion,-ine1

“He was still bearded, still rather leonine, but he was better groomed than in those days in India.”

- Anne Warner, The Tigress

Noun

[oh-ver-cher, -choor ]

1. an opening or initiating move toward negotiations, a new relationship, an agreement, etc.; a formal or informal proposal or offer:

overtures of peace; a shy man who rarely made overtures of friendship.

2.Music.

a. an orchestral composition forming the prelude or introduction to an opera, oratorio, etc.

b. an independent piece of similar character.

3. an introductory part, as of a poem; prelude; prologue.

4. (in Presbyterian churches)

a. the action of an ecclesiastical court in submitting a question or proposal to presbyteries.

b. the proposal or question so submitted.

Verb (used with object)

5. to submit as an overture or proposal:

to overture conditions for a ceasefire.

6. to make an overture or proposal to:

to overture one’s adversary through a neutral party.

Origin:

First recorded in 1300–50; Middle English, from Old French; see overt,-ure; doublet of aperture

“High culture is the ability to hear the William Tell Overture and not think of the Lone Ranger.”

- Arthur D. Hlavaty

Noun

[sahy-uhn ]

1. a descendant.

2. Also ci·on . a shoot or twig, especially one cut for grafting or planting; a cutting.

Origin:

First recorded in 1275–1325; Middle English: “shoot, twig” <Old French cion, from Frankishkī- (unattested); (compare Old English cīnan, Old Saxon kīnan, Old High German chīnan “to sprout,” Old English cīth, Old Saxon kīth “sprout”) + Old French-on noun suffix

“Doctor Bataille, poor man, is the scion of an ordinary ancestry within the narrow limits of flesh and blood.”

- ARTHUR EDWARD WAITE, DEVIL-WORSHIP IN FRANCE

Chaucer and Old Norse Mythology

Chaucer and Old Norse Mythology Rory McTurk School of English, University of Leeds In a paper currently awaiting publication I have argued that the story in Skáldskaparmál of Óðinn’s theft of the poetic mead is an analogue to the story told in Chaucer’s House of Fame, for three main reasons. First, both stories may be said to involve an eagle as a mediator between different kinds of poetry: in…

fancy

Fancy,in the adjective sense of pressed linens, champagne and marble, feels less interesting than the verb varieties: “to believe, to visualize or interpret as,” and my favorite, “to like or have a fancy.” I think the sound of fancyingsomeone is sweet, like you consider them as being of a special elegance and loveliness.

What I quite like about this word is that it is apparently a contraction of the word fantasy.Around the 15th century, it was originally spelled fantsy, specifically adopting the meanings of “whim, inclination.” Our current definitions of “fine, elegant,” appeared later.

The Middle English fantasy (also spelled fantasye), came from the Old French fantasie,from the Latin phantasia, meaning “a notion, phantasm, appearance, perception.” The root Greek was the term φαντασία phantasía,a derivative of the verb φαίνω phaínō,which is “to make visible, to bring to light, to cause to appear.” You might notice its similarities to the related word for “light,” φῶς phôs,from which we get other English words like photograph,photon, etc.

Ultimately, these are all attributed to the Proto-Indo-European root bheh-or sometimes bha-,meaning “to shine.”

elf

Elves are fun because there are so many vastly different interpretations. Everything from Santa’s toymakers to Elrond and his court qualify into our concept of elven forms.

Generally speaking, we might define elfas being a “spirit, sprite, fairy or goblin; some kind of usually mischievous supernatural creature.” This same definition existed for the Middle English term elf,alternately recorded as alfeorelfe.In Old English, the word was ælf,still retaining its meaning of “sprite, incubus or fairy,” but specifically with a masculine connotation. The feminine version of the word was ælfen, which interestingly is the predecessor to our modern adjectival form elven.

The word branches out of the Germanic family, and we can point to some other connected words in Old High German, like alp which meant “nightmare.” There is actually an Old English cognate which is ælfádl, also meaning “nightmare,” but more literally, “elf-disease.” Another interesting elf-induced sickness was though to be hiccups, which is reflected in the OE translation ælfsogoða.

Beyond this era of the Old English and German there is some debate about where the words originally sprouted from. The trail may be related to albusoralphoúsἀλφούς, the Latin and Ancient Greek terms for “white” respectively. The cultural theory implies that elves were considered beings of light, brightness and beauty, and thus as this concept evolved from those ideas, so did the English form out of the adjectives.

mizzle

This word is actually very funny to me, because it did not remotely go where I expected.

The word this week is mizzle, which is a rather lovely way of describing a light, drizzly rainfall. This comes from the Middle English misellen, of the same meaning, “to rain gently.” The question of borrowing is a little fuzzy, but it likely was adopted from either an Old Dutch or Low German variation, both meaning something more akin to “mist.” At this point, though, any inquiry further back relates to words meaning “urine, or to urinate.” This root exists in a lot of Germanic languages, and they are likely additionally connected to the Latin mēiō, which means, quoted from the 1890 Charlton T Lewis, An Elementary Latin Dictionary entry: “to make water.”

Ferrets are very cute. This is a scientific fact. They are a long, furry, domesticated subtype of the European polecat. They have a look on their face like they are ever so slightly irritated at having been recently woke up, and I love them very dearly.

Anyways, the Middle English feret (also documented as fyrette), was borrowed from the Old French firet, which is a derivative of the Latin fūr,meaning “thief.” This is also a cognate to the Ancient Greek φώρ phṓr,also “thief.”

What I find fun about the Ancient Greek, is that it also can be used to refer to a bee, specifically a “robber bee.” I absolutely love the fact that both the Latin and Greek chose to refer to tiny animals as being the perpetrators of some thievery, namely that they “carry things away,” from the Proto-Indo-European bher- meaning “carry.”

I also particularly enjoy the fact that this Latin also gave us furtive, “done in a sneaking, secretive way,”more specifically from fūrtīvus,“stolen.”

dandelion

I absolutely never noticed this, but now that I’ve seen it, I cannot believe it never occurred to me. Dandelion, the flower of my childhood, is a borrowing from the French name dent de lion, which is literally “lion’s teeth.”

I think this is the most adorable thing and I love it very much.

The French came through the Middle English, spelled alternately as dantdelyonordendelyoun.This phrase has also popped up in related languages, such as the Welsh dant y llew, and the Spanish diente de léon.

At the very base of it is the Latin dens leonis, which translates pretty much the same as its linguistic descendants.

Interestingly, in looking around some dictionaries, I found this entry from an anthology of plants written in 1578:

The great Groundlwel, hath rough whitish leaves, deeply jagged and knawen upo both sides, like to the leaves of the white Mustard or lenuie. The stalke is two foote high or more: at the top where-of growe smal knoppes, which do open into smal yellow flowers the which are lodenly gone, changed into downie blowbawles like to the heades of Dantdelyon, and are blowen away with the winde.

I’m not sure I transcribed that right, but I really like the last bit: “changed into downie blowbawles like to the heades of Dantdelyon, and are blowen away with the winde.”

This is an interesting doublet because it is a great example of how English absorbs all sorts of lexical items from other languages even when it basically already has one in the same color. Also, it’s been barely a week and I miss Halloween.

Spirit: “The soul of a person or another creature.” We can trace this back to the Middle English spirit, of several different additional meanings, including “vital breath, animation, divine, indescribable, immaterial creature.” English borrowed this from the Old French espirit,from the Latin spiritus.This Latin term was a derivative of another Latin word, spiro,meaning “I breathe, respire, live or blow.”

Ultimately, the word is probably from the Proto-Indo-European root peisorspeis, “to blow.”

Ghost: “The spirit, soul or animation of a man, the shadowy mirror image.” The modern English evolved from the Old English term gast, “breath, good or bad spirits, angels, demons.” Interestingly, in older translations of the Bible, since the English language had yet to adopt the Latin derived term spirit,any instances of spiritus were translated asgast,which is why most old Christian writing uses Holy Ghost.

The Old English also has an additional meaning branch as well, which is “afraid, terrified,” related to the verb gaestan, “to frighten, afflict or torment.” We likely pulled this through Proto-Germanic from the Proto-Indo-European term gheis,meaning “shocked, agitated.”

Spiritand ghostare now somewhat interchangeable, and we usually use them to refer to both the “souls of the deceased,” and “supernatural creatures.” I also find other languages’ ways of describing souls or spirits interesting: French revenant(literally “returning (from another world)”), Old English scinn(related to scinan, “to shine, illuminate”), Greek φάντασμα phantasma,(related to words for “light, sight, vision”), and French spectre (from the Latin spectrum,which is related to other Latin terms for “to see, appearance”).

Vespertineis a beautiful word meaning “of or related to the evening.” It is an old word, from the Middle English vespertyne,which is “belonging to evening, evening dew.”

The Latin form from whence the English comes, was vespertinus,meaning strictly “evening.” This is an adjective version of the noun vesper,which was used to either describe “evening” or “the evening star,” an entity we now recognize as the planet Venus. The Latin was a cognate to the Ancient Greek ἕσπερος hesperos,of the same definition, which is visually a little closer to the Indo-European root, u̯esperos, “evening.”

Interestingly,vesperwas also adopted into English apart from it’s descriptive form, and has been used to refer to the “evening star” as well as “church services held during the evening.”

Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote,

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote,

And bathed every veyne in swich licóur

Of which vertú engendred is the flour;

Whan Zephirus eek with his swete breeth

Inspired hath in every holt and heeth

The tendre croppes, and the yonge sonne

Hath in the Ram his halfe cours y-ronne,

And smale foweles maken melodye,

That slepen al the nyght with open ye,

So priketh hem Natúre in hir corages,

Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages.

- Geoffrey Chaucer, The Canterbury Tales

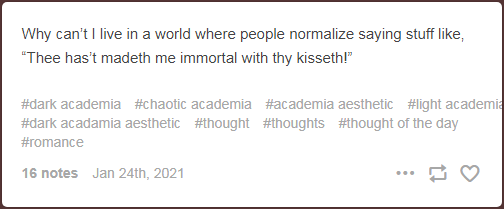

Because this is terrible grammar.

I’m hardly an expert in old-timey English, but:

1. “Thee” is accusative/dative (think “to you”). Thou is the right word.

2. “Has’t” is short for “has it”.

3. “Madeth” is not a word.

4. Present Perfect in Middle English is a can of worms. I would settle for “Thou madest”.

4.1 That said, if you really want Present Perfect, you want to use the past participle - “mad, maked, ymad, ymaked”, which gives us “Thou hast maked” or even “Thou hast maad”, as per Chaucer.

[…] thou hast maad a ful gret lesing here

4.2 And in Shakespearian English, it’s “thou hast made”:

For thou hast made the happy earth thy hell

5. “Kisseth” is a verb. Kiss, a noun, is “kisses” in plural. If “kisses” is good enough for Shakespeare, it’s good enough for thee.

A thousand kisses buys my heart from me

6. And if I want to be pedantic, I’ll suggest substituting “eternal” for “immortal”.

Thou hast made me eternal with thy kisses.

thesaurus abuse is a dangerous form of substance abuse

syrup (14c), from the Old French sirop, via the Italian siroppo, via the Arabic sharab, meaning “beverage, wine,” and literally “something drunk.”

sorbet (1580), “cooling drink of fruit juice and water,” from the French sorbet, via the Italian sorbetto, via the Turkish serbet , via the Persian sharbat, via the Arabic sharba(t), “a drink.” Probably influenced by the Italian sorbire, meaning “to sip.”

sherbet (17c), originally zerbet, “a drink made from diluted fruit juice and sugar.” Directly from the Turkish serbet.

sugar (13c), from the Old French sucre, via the Medieval Latin succarum, via the Arabic sukkar, via the Persian shakar, via the Sanskrit sharkaraoriginally meaning “grit” or “gravel.”

spinach (15c), from the Anglo-French spinache, via Old French espinache, via Provençal espinarc, probably via the Catalan espinac, via the Arabic isbanakh, via the Persian aspanakh.

orange (14c), originally the fruit.

Old French orange, orenge

Medieval Latin pomum de orenge

Italian arancia, narancia

Arabic naranj

Persian narang

Sanskrit naranga-s

mattress (13c), via the Old French materas, via the Italian materasso, via the Medieval Latin matracium, from the Arabic al-matrah, meaning “the cushion,” literally “the thing thrown down.”

Pike (the weapon) and pick (the tool) come from the Middle English pik/pyk andpic, respectively, all via the Old English piic, “pointed object, pickaxe.”

The verbs pickandpeck also come from Middle English, in this case pikenandpicken, respectively, all via the Old English pician “to prick,” and perhaps from the Old Norse pikka.

Pickaxe is often thought to be a compound word of “pick” and “axe,” but is actually from the Middle English (13c) picas,ultimately from the Medieval Latin picosa. In 15c it was altered via folk etymology to include axe. Axe itself is from the Old English æces/æx, via the Proto-Germanic akusjo, via the Proto-Indo-European agw(e)si-.

In some Middle English and Early Modern English dialects, pickandpitch were synonymous. Because of this, we also have pitchfork and piggyback. Pitchfork was originally pic-forken in Middle English (13c), and piggyback was originally pick pack (1560), from the act of pitching a bag over one’s shoulder.

Pickle (15c) is unrelated, and of uncertain origin.

Toothpick is Early Modern English, but Old English had toðsticca, “tooth-stick.”

Ginger (14c), is from the Old English gingifer/gingiber, via the Late Latin gingiber, via the Latin zingiberi, via the Greek zingiberis, via the Prakrit singabera,via the Sanskrit srngaveram.

Gingerbread (13c) was originally gingerbrar, from the Old French ginginbrat, meaning “ginger preserve.” It was changed to gingerbrede in 14c via folk etymology.

Penthouse, from the Middle English pendize(14c), via the Anglo-French pentiz, via the Old French apentis meaning “an attached building” or “appendage,” via the Medieval Latin appendicium, from the Latin appenderemeaning “to hang.” The modern spelling (c. 1530) is a folk etymology of the French pente(”slope”) plus house. The modern meaning is from 1921.

Why aren’t all greyhounds gray? Surprisingly, the first part of this compound word has undergone three meanings without changing form much. The Old English grighund/greghund came from grig, a Nordic word meaning “bitch,” and hund, meaning “dog.” In Middle English, the word was altered by Grew, meaning “Greek.” In Modern English, the first part of the compound was understood to reference the color gray.

Posthumous (15c), from the Latin postumus, meaning “last,” and originally used to describe a last-born child. In Late Latin, it was influenced by humare, “to bury,” and took on the meaning of “a child born after the death of their father.” Old English had æfterboren (”after-born”) to describe this final meaning.

Innocent is often speculated as having the same etymology as ignorant: from the Latin for “not knowing.”

This much is true for ignorant (14c), which, via the Old French ignorant, is from the Latin ignorantia/ignorantem, “not to know.”

Innocent (14c) also came via Old French (inocent), but from the Latin innocentem. This word, in turn, is from the prefix in- (”not”) and nocere, meaning “to harm.” Innocent, then, doesn’t etymologically mean “knowledgeless,” but rather “harmless.”

Despite similarities in spelling and meaning, islands andisles are only related through folk etymology.

Isle (13c) comes from the Old French ile/isle, originally via the Latin insula.

Island (16c) comes from the Middle English yland and Old English igland, from the root ieg(from the same root as aqua-), meaning “island,” and a redundant -land.

The spelling of isle was altered in 16c to reflect its Latin roots, and so the spelling of island was also changed due to the assumption that its etymology was isle+land.

We interrupt your regularly scheduled book blogging to bring you this important message. My bestie bestest most best fabulous wonderful amazing friend Morgan lent me her copy of The Fall of Arthur. It is beautiful and I was in love before I even opened it. Tolkien writes in Modern English but in Middle English style, preserving the alliterative verse form and utilizing the standard rhythm, INCLUDING THE CAESURA. YO.

So in a lot of Middle English alliterative verse there’s this nifty little thing called the caesura. In poems like Sir Gawain and the Green Knight the caesura splits each line into two distinct sections. It’s basically invisible unless you read the poem out loud with correct pronunciation, at which point it becomes an integral part of the recitation. Most translators are forced to abandon the caesura when turning Middle English into Modern English, so most students never encounter it except as a dead device. This is a shame. I have a lot of love for the caesura because a) it’s a fabulous word, b) I can read Middle English and when reading poems out loud it sounds so sexy, and c) the skill required to write a poem in alliterative verse with a perfect meter is astronomical, and dropping the caesura in translation, unavoidable as it may be, diminishes the apparent skill of Middle English poets.

In short, Tolkien was very smart, and when writing his poem about King Arthur he elected to follow in the footsteps of the greats and write an alliterative poem in Modern English that preserved the Medieval meter. That’s badass.

Post link