#personal identity

“I find I exist most authentically

somewhere between

cursive and chicken scratch—

that is to say

in written word,

not lens,

for photography fails and deceives

in so far as it tries

to contain me

in an immortalized image

whereby the eye defines me

a perceived singularity.” - d.c.

The personal identity of bodies

- ‘She’s not your mum anymore!’ In Shaun of the Dead (2004) Shaun (Simon Pegg) must decide whether to shoot and kill his own mother—or, rather, the zombie occupying her body. Shaun initially acts like the person is his mother by virtue of the body; he attaches her to it. But he reverses his position, thus accepting that his mother died when her body was zombified and lost her mind.

- InThe Lion King (1994) eventually Simba reaches a fork in the road: he must choose between his past life, rooted in family legacy, or his newfound independence. Will his choice define him?

- InFuturamaS5E8 Fry faces a similar dilemma to Simba’s: year 2000 or year 3000?

- InTotal Recall (1990) Douglas Quaid (Arnold Schwarzenegger) wrestles with the contents of his memory to determine whether he is a miner or a secret agent. Memory and reality are blurred over the course of the story. We are encourage to distrust psychological criteria of identity less, particularly those premised on memory.

- InWestworldDolores, as a transplanted consciousness, is able to occupy different bodies to take revenge on humans—something which defines her life, given her past enslavement. Will it ever be possible to construct a being whose identity is transferrable like this? Or is the body too important for identity?

- InBlack MirrorS2E2 we watch on as a bewildered woman, who has had her memories wiped, be hounded by members of the public for a prior crime she obviously doesn’t remember. Can there be justice without memory?

In virtue of whatare you the person who lacked control of their bowel movements and who cried for cuddles with Mummy? This is an important question—well, sort of.

Politics, law, love, friendship—they all assume singular, persisting entities. But upon what basis are you an entity and how do you persist?

Here are two conflicting options: the self either has a psychological or a biological status. One person can’t have both. Previously, we ran through John Locke’s argument that a person goes where their consciousness goes. Now let’s consider the importance of the body.

A thought experiment

If Locke is right, it is theoretically possible to ‘download’ a person and ‘upload’ them into another body. To quote Marya Schechtman (2005): ‘Why should it matter to us that the memory experiences in question be in one substance rather than another if it does not change the character of consciousness?’

But one philosopher, by the name of Bernard Williams, created a thought experiment which undermines this position. Imagine you are about to switch from body A to body B(a stranger goes in the reverse direction). You are told that, afterwards, one of you will receive $100,000; the other will be tortured. Now answer this: would you rather be AorB? Rationally, B is the answer.

However, Williams asserts your fear of torture won’t be shaken off, for you identify with your body, expressing fear qua being ‘in’ that body—a fear which isn’t subdued by your thoughts.

Imagine further you’ll be tortured tomorrow but your memories will be wiped before the torture takes place. You shouldn’t be terrified—psychologically, the person won’t be you since your mental states won’t be retained—but you are scared, right?

Therefore, psychological accounts fail to strip minds from bodies. We are concerned for our bodies regardless of our psychological states. So body-switching cases don’t work.

Owning one’s body

To this effect, dying philosophy teacher Gretchen Weirob argued to a friend that even if there is somebody exactly similar to her in another body, it could never be her. Only this body—‘overweight, injured, and lying in bed’—could house her. There might be a Gretchen copy somewhere, indiscernible to others, but that Gretchen won’t possess the original identity.

How about you: can you imagine ever being anchored to another body?

⁂

We take strong ownership over psychological aspects of our lives, too. Numerous works of fiction explore personal identity in accessible yet exciting ways, asking us to consider the extent to which we are defined by our bodily or mental properties. We feature six above.

⁂

Hallucinogenic drugs apparently break up the unified structures of an embodied self. Is the self really that flimsy a concept?

Post link

The personal identity of clones

This week we focus on personal identity. And today we discuss the sameness of clones.

Let’s go.

Personal identity

PhilosopherJohn Locke argued that a person goes where their consciousness goes; their personhood consists in things like memories. Therefore, a person must be able to extend their consciousness backwards to past events to be the person presently who experienced them.

Some absurdities arise, however. Why trust memories to solidly define us? I might have a genuine belief that I am Ash Ketchum but, alas, I am not ☹ And what if I was asleep or drunk, beyond memory collection: was I really not there? Still, there is something interesting going on here, for where a person is apparently situated is in their consciousness.

In one of Locke’s examples a prince, via his consciousness, is able to enter a cobbler’s body. He takes his ‘princely thoughts’ with him.

Clones

Let’s apply Locke’s view to clones by asking: if a person is cloned, are there two of the same person?

No. Locke would have denied this claim. One’s point of consciousness can move between bodies but ‘the soul’ cannot be in more than one place at once.

This is bad news for a clone: the original soul stays with the host. The clone may faithfully recollect past events and share personality traits. They can live indistinguishably in ignorance. But their life can be deflated with one prick of the truth, with which they will realise that their life is a lie: that there is no organic connection to their memories; that they did not experience those events.

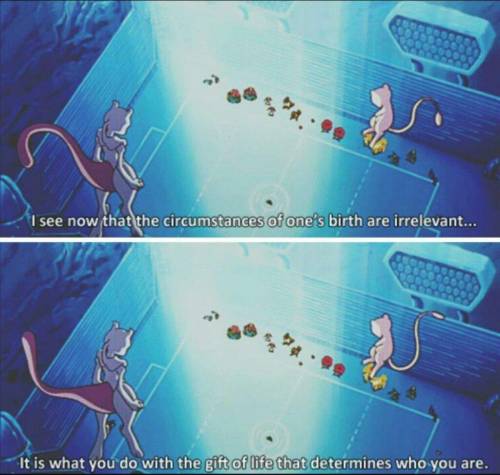

These are truly gutting thoughts to consider. But there is hope in life anew—that is, if we follow Mewtwo in Pokémon: The First Movie(1998):

‘I see now that the circumstances of one’s birth are irrelevant; it is what you do with the gift of life that determines who you are.’

Cloning imprisons a copy of the soul. However, a unique vantage point is created from which a clone becomes increasingly autonomous. They gather new experiences, forging new memories. Their soul is new. They are original. Their life belongs to them.

Nice one, Mewtwo.

⁂

Some afterthoughts are due.

What is it to be somebody connected through time? After all, our cells die and are recycled, our personalities change, and our memories falter. On what grounds do we persist?

For Locke, bodies are less important for personal identity than psychological states (cf. bodily vs. psychological criteria). Sidestepping accounts of bodily criteria, Lockeans think our identities are born in memories and other features of psychology. Schechtman (2005) argues that self-narratives and elements of unconsciousness play a part too.

In memory we are often misguided. Memories alone, as objects of thought, are residuals of imperfectly recorded events—events which occur infinitesimally in the present and are forever being replaced. Our connections to those memories are loose. They are flimsy. The memories lose their vivaciousness over time.

But perhaps beneath memory we are still made. To quote Ralph Waldo Emerson:

‘I cannot remember the books I’ve read any more than the meals I have eaten; even so, they have made me.’

Post link

The Philosophy of Moon

Moon (2009) is a quietly disturbing sci-fi. Through the crisis of one man we are asked to ponder some deep philosophical questions, not just about him but about ourselves—all without being bombarded with unnecessary action.

Sam Bell’s reality is shaken to its core in Moon. Instead of disregarding an event as a glitch and moving on, Sam follows the scent of suspicion to agitate and uncover something bleak. He marches out to the Moon’s silent and eerie surface and uproots it—for the sake of truth.

Uncomfortable and confounded by the answers he receives, bothered by his subsequent physical and mental decay, we can only watch on and ask: ‘Wasn’t darkness better than the truth?’

⁂

Read more here. There is plenty of philosophy to find therein: ethics, metaphysics, and existentialism. Expect discussions of human cloning, personal identity, and purpose.

Post link

The ethics of cloning

(Pictured: Dolly the sheep with her Scottish Blackface surrogate mother. One mother wasn’t enough for Dolly; two others helped bring her into existence, providing the egg and her DNA. Born in 1996, Dolly died in 2003 of a fairly common kind of lung cancer in sheep. She nonetheless lives on (in stuffed form) at the National Museums Scotland, close to home.)

Here’s something to think about in preparation for our next article: how ethical is cloning? Let’s start with non-human animals.

Allow me to introduce Dolly the sheep (left). Born to three mothers (one of whom is on the right) in Scotland in 1996, Dolly was the world’s first ever mammal clone. In the UK cloning for the purposes of scientific research is legal upon application.

But in the aftermath of the Dolly’s cloning The European Union deemed the process to be highly controversial. Representatives said ‘the border was too close between animal cloning and cloning on human being[s]’—the ‘slippery slope argument’.

So human life is too precious to clone; animal life is not? In fairness, self-awareness means cloning threatens our existence in special ways. For example, if you were cloned, there wouldn’t be two of you: such a claim would be a contradiction. There is only one you, to whom no one can be identical. But while a clone cannot share your unique identity and your future experiences, they will be fighting for the same identity as you: a stirring thought. Plus there are ethical concerns even with cloning at the primitive stage of human development. These include the ‘death’ (destruction) of many embryos, which are given the moral status of beings, and steps towards eugenics.

However, there are several avenues down which human cloning serves tangible benefits to society. Cloned embryos can be used to create cells in the development of treatments for currently incurable diseases. Reproductive cloning offers hope of parenthood to infertile individuals, same-sex couples, and couples who cannot produce together, enhancing their dignity and familial liberty and bypassing the need for cell donation.

With science we look for ways to design better quality of lives, perhaps at a moral cost. After Dolly the European Union conceded there’s a debate to be held around human cloning for the purposes of medical research. And there’s precedent: in the US human cloning isn’t completely illegal, depending on where you are, and in the UK experimental stem cell research for treating diabetes, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease is legal, as is three-person in vitro fertilisation.

We continue to foresee ways in which cloning will affect our moral outlooks (e.g. in fiction) and, eerily, who we think we are. The reality of human cloning may be far off. But that won’t stop philosophers, story writers, and us from debating moral issues now in preparation for such a time.

Post link