#sindarin

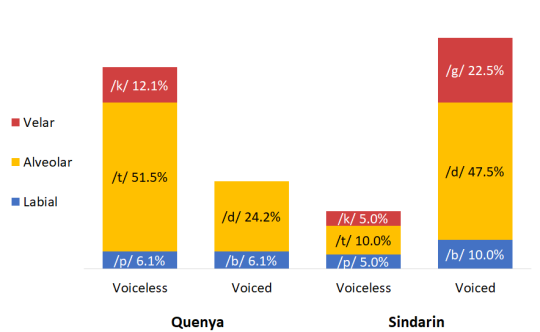

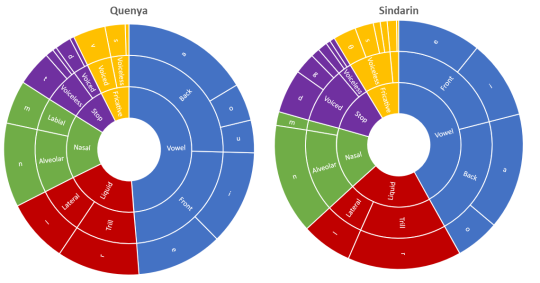

I recently wondered if there was a way to visualise some aspects of the phonological character of Quenya and Sindarin, and the differences between them. The following charts are based on the Namárië poem for Quenya and The King’s Letter for Sindarin. I did a broad phonological transcription for both, then ran frequency counts and relative frequencies on the phonemes. And here are some of the results!

1. Tolkien liked his alveolar stops! And whilst Quenya shows a preference for voiceless stops over voiced stops, the reverse is true of Sindarin.

Part of the reason why the Sindarin voiced stops are so prevalent is due to the extensive consonant mutation system of Sindarin. In the case of stop consonants, the soft mutation turns voiceless stops into voiced stops in certain phonological and/or grammatical environments.

2. Both Quenya and Sindarin prefer front vowels over back vowels, i.e. /i/ and /e/ are preferred over /u/ and /o/ (the Sindarin text happened not to have /u/ at all). The low vowel /ɑ/ is the most frequent vowel in both languages.

Tolkien wrote that in Quenya, the vowel sign for /ɑ/ was often left out in writing, e.g. calma ‘lamp’ could be written as clm (using the equivalent Elvish characters, of course!).

3. Quenya seems to be more vowel-heavy than Sindarin, but Sindarin’s consonants seem to have a larger proportion of liquids, nasals and fricatives … and Sindarin /n/ and /r/ are super-popular!

Almost half of the phonemes shown for Quenya are vowels, compared with two-fifths in Sindarin. As Tolkien wrote, Quenya words more often ended in a vowel, whilst those in Sindarin more often ended in a consonant.

In Sindarin, about two in seven phonemes (of those shown in the chart) is either /r/ or /n/! In Quenya, /n/ appears about twice as often as /m/, but in Sindarin, /n/ appears about seven times more often than /m/!

A secret vice - this was how J.R.R. Tolkien described his love of creating, crafting and changing his invented languages. With the popularity of his books and the modern film adaptations, the product of this vice is no longer as ‘secret’ as it once was – almost everyone will have heard of Elvish by now; some will have heard of Quenya and Sindarin; and a small number will have heard of more besides …

I started thinking about the theme of this post having read this article from the Guardian on constructed languages (or ‘conlangs’):

Conlangs can be used to add depth, character, culture, history among many other things, but I think that Tolkien’s invented languages are in a class apart from other famous invented languages, e.g. Klingon, Na’vi, Dothraki, Esperanto, etc.

What many people don’t know is that Tolkien’s Elvish languages weren’t ‘invented for’ the Lord of the Rings, or the Hobbit or even what was to become the Silmarillion. In fact, in many ways it is more accurate to say that these stories and legends were invented for the Elvish languages!

Tolkien’s Elvish languages began to grow at about the time of the First World War, and they continued to grow for the rest of Tolkien’s life. Tolkien gave to two of these languages, Sindarin and Quenya, the aesthetic of two of his favourite languages, Welsh and Finnish respectively. However, rather than develop comprehensive dictionaries and grammars of the Elvish languages, Tolkien approached their invention from a primarily historical and philological perspective – something that the other famous conlangs do not do to anywhere near the same extent.

Sindarin and Quenya were designed to be natural languages, i.e. languages with their own irregularities, quirks and oddities (like real-world languages) but whose peculiarities would make sense when looked at from a historical linguistic perspective. Furthermore, Sindarin and Quenya are related languages, i.e. they share a common (and invented!) ancestor. Whenever Tolkien compiled anything like a dictionary, it was more akin to an etymological dictionary or a list of primitive roots and affixes. He would build up a vocabulary using these roots and affixes then submit the results to various phonological changes (as well as language contact effects, borrowings, reanalyses, etc thrown in for good measure! Did you know that the Sindarin word heledh ‘glass’ was borrowed from Khuzdul (Dwarvish) kheled?). The result is a family of related languages and dialects.

But these languages and dialects needed speakers, and their speakers needed a history and a world in which this history could play out. Tolkien believed that language and myth were intimately related – the words of our language reflect the way we perceive the world and myths embody these perceptions and are couched in language, yielding a rich melting pot of associations. To appreciate something of what Tolkien might have felt consider the English names for the days of the week or the months of the year. Why do they have the names they do? What does this tell us about our heritage and cultural history? What does it say about what we used to think and feel about the world? Now imagine thinking like this about other words … I found out earlier this week that English lobster is from Old English lobbe+stre ‘spider(y) creature’ (incidentally, lobbe ‘spider’ provided Tolkien with the inspiration for Shelob, the giant spider from The Two Towers (or, if you’re more familiar with the films, The Return of the King)). That is the kind of philological delight Tolkien wanted Sindarin and Quenya to have, and they do (nai elyë hiruva)!

The walls of Caras Neldorath.

Would you stand before these gates as a friend, or as an enemy?

It is an immense team effort by the Lager der Elben construction team to put this stockade into place for each Epic Empires. The modules have to be carried to the location and assembled there, and after the event, they are again disassembled and carried to their storage location. My part in this was very small: During the original planning phase I gave feedback and Ideas to how it looks from the outside and what it should support gameplay-wise: Limited cover for defending archers and plenty of space where enemies can try to climb the wall.

The photo was taken by The Kelric View

It’s the season to listen to Mornienna’s cozy elven winter song again.

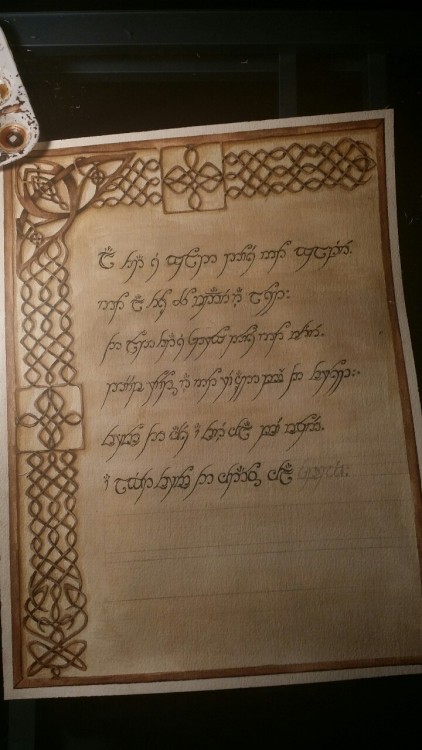

Some process pictures and the final result of my latest piece.

It’s the “Strider’s Riddle” quote from Tolkien’s LotR series, written in the elvish language of Sindarin. In the books, it was written by Bilbo Baggins about Aragorn, or “Strider”.

“All that is gold does not glitter,

Not all those who wander are lost;

The old that is strong does not wither,

Deep roots are not reached by the frost.

From the ashes a fire shall be woken,

A light from the shadows shall spring;

Renewed shall be blade that was broken,

The crownless again shall be king.”

***

12"x16” Watercolour // November 2014

***

This piece was done as a gift, and is not for sale. However, if you would like a similar quote or piece, there is a link to my etsy shop at the top of my blog, and feel free to contact me about ordering a custom piece.

Great holiday gift idea for a Lord of the Rings fan in your life!

Post link

On this day in 1977, Orlando Bloom was born. He made his breakthrough as Legolas Greenleaf in Peter Jackson’s the Lord of the Rings trilogy.

Newsfeed #97 March 8, 2018 (8 Súlimë)

NEW BOOK ANNOUNCEMENT: THE STAND-ALONE SAGA

First of all, I’m not dropping everything to write this particular book (I don’t know why people fear that). The “new” book is not as “new” as I am implying. The story (like the trilogy) is a long and winding one.

When I began outlining the Elves of Mirkwood, naturally people wonder “where are all these elves coming from. For example, it is no secret Thranduil’s cousin Elranduil married a Noldorin (Ardúin) and Thranduil’s wife is a Nandor (Danwaith)–the last of the remaining ones. Nearly all of the main characters have a back story (and after stories), so I had written part of those around the time I began The Kingdom of the Woodland Realm Trilogy. They were going to go into the Appendix (which at the time included Legolas’ Journals). When I changed the format of the book–having the story told by the four generation of elves–two being rulers and one being an heir to the Woodland Realm–I was free to do with the back stories what I wished–especially the one about the origins of Êlúriel.

It doesn’t have a title yet; it is not put together as well as the other books in the trilogy–even Legolas’ story is already planned from beginning to end. This new book will be part of the Appendix, unless it’s longer than 200 pages. There is a reason for that:

515 pages of Book II: The Saga of Thranduil (original version) is already a ream; its extended version will be at least 600pages in its final form and Book I and Book III are currently estimated to be 500-600pages each–then there’s the extended version of Book III which will more than likely be around 500-600pages long. When I put the trilogies together, that’s a lot of paper to add something 200+ pages long. I’m already over 1100 with Book I/Book II (both versions) not including Book III.

Tolkien’sThe Lord of the RingsTrilogy* in one volume is 1178 pages (including the Appendix; 1031w/o).So you can see I have a doorstop in the making. And even though this new “volume” will mesh with the trilogy (not unlike the STARZshowThe White Queen–based on three books by Philippa Gregory that tell three different sides of the same history; only in this case there’s several sides talking when you add Iarûr (Prologue of Book I) to the stories of Orothôn,Oropher,ThranduilandLegolas), I still have to decide at some point how long will it need to be to fit into the appendix or if it should just stand-alone.

I am still trying to decide whether to cut Book I in half as itself will contain two stories told by two elves–both crossing over at a pivotal event from one POV to another (hard to do especially I will have to eventually make that transition for all three of the original books). I do that, TKWRT won’t stand for TKWR TrilogybutTKWR Tetralogy. That won’t be decided until all three books are complete, though.

You are watching a novel in progress–I like to call it a reality show since readers are literally reading TKWR Trilogy in evolution. There’s is always something new coming around the corner and editing something like this requires someone that has flown over the Cuckoo’s Nest a few times and is literate in Tolkien Languages–especially Adûnaic. That hasn’t been added yet–nor has all of the Quenya. (Quenya is the hardest of the two Elven Languages known; That is why no one is out there selling “Learn Quenya” (even though Sindarin is Quendi for “Grey-Elven Language”). All the languages change with each new age/generation (as all languages do) which makes it impossible to say which “literary” version you are reading–and it gets worse with Tengwar where there’s far more to it than what most people think.

Adûnaic is harder still, even though Akallabêth is “The Down Fallen” in Adûnaic in The Silmarillion. What you get to read now is my “short-hand” for some things in Sindarin that may be translated eventually into Quenya–especially in Eryn Galen. Oropher didn’t like Sindarin at all (hence why it was unknown whether Thranduil spoke it). There is a reason Oropher didn’t like it and unless you adore reading thousands of pages of Tolkien’s notes in the form of 12+ volumes of Middle Earth History and his other works, you won’t find that reason (mostly because Oropher is in only one book of all books dealing with ME Histories by Tolkien and he’s somewhere else altogether)–hence the reason my book will have a very large bibliography. Yeah, this is an in-depth book I’m writing. I’m a glutton for punishment.

So, that’s it for now; back to work. I have a bunch of elves stuck in Ossiriand for a moment waiting for a few baby elves to be old enough to continue the journey into the West (by “west” I mean some will get lazy somewhere around Beleriand and hang out in Doriath with King Thingol and his Queen Melian). Also, I’ve been advised to use my real name in order to get the accounts for this book and myself verified ✅. Thranduil has come a long, long way from where he started.–JMM (Jaynaé Marie Miller).

*The Lord of the Rings is actually not a trilogy. It was originally supposed to be six books–a hexalogy, so to speak. In fact, in the table of contents, you’ll notice that each of the “books” has “two books” within them.

Images: ©2013. Warner Brothers Pictures. The Hobbit: Desolation of Smaug. All Rights Reserved.

Post link

For writing a request that asks for “Thranduil + fluent Sindarin eloquence”, I am back in the cesspit of Sindarin linguistics.

Lenition.

Soft mutation.

Nasal mutation.

Liquid mutation.

Prepositions without any mutation.

*whispers* No… nooooo, actually, it does not… *sigh*

update on elf practice:

decided to start with Sindarin because i know way less about it than i do about Quenya, which i’m finding out is par for the course for everyone else on Earth. i’ve been enjoying Fiona Jalling’s A Fan’s Guide to Neo-Sindarin(First Edition) for my starting book, which has been a nice explanation as to why i knew so little about it in the first place, just in the first chapters alone.

also surprise, i like having structure, so I’ve been regularly answering review questions as part of my reading. doing the review questions was fine pretty much up until i had to start typing with IPA notation??? i may shift my notes over to physical ones just so i don’t have to type out this extremely helpful but still accursed homework. there’s uhhhhh a lot of stuff in this book involving IPA and no sign of either Certhas or Tengwar, which is a crying shame.

for my shelf, with my wonderful stimmies, i have added in David Salo’s A Gateway To Sindarin(which is Exceptionally Dense), to have a second modern perspective on Sindarin. this one works better as a comprehensive reference than a textbook, especially if you have no linguistic experience. in its favor, it actually covers the use of the Tengwar and Certhas– just, briefly, over the course of maybe six pages, with some clarifications for the variable modes.

and of course, since i spaced and forgot i’d probably get a dictionary in both of these books, i also picked up J-M Carpenter’s Sindarin-English & English-Sindarin Dictionary (4th Edition). this is absolutely the most comprehensive and up-to-date standalone dictionary I could find; the update to 4th Edition was in late 2019 and has a number of words I’d been missing, as I’d been working from a dictionary from 2008. it is not thick; there’s just not enough words in the language to merit more than two hundred pages, and I doubt there ever will be. however, the size is very -pleasant and it looks like there’s plenty of space in the margins for sticky notes and annotations over the years.

Elvish Months of the Year:August

In the High-Elven tongue, the eighth month of the year was named Úrimë(Urui being its Sindarin equivalent). Now, the root úr— comes from the Quenya word úrë, meaning ‘heat’. From this, we can conclude that Úrimë was the month of hot weather.

July—another month gone by, and with that comes a new Elvish Lesson. So in the High-elven tongue, the seventh month of the year was named Cermië(Cerveth being its Sindarin equivalent). As to the meaning of that name, there are actually surprisingly few references. However, in my research I did discover that one of the meanings of the Quenya root ‘cerm’ is ‘to give’. By this, I’m assuming that Cermië was the month of harvest or plenty (though don’t take my word for it).

As for the above picture, July always reminds me of Lothlórien somehow.

June at last, which means summer is finally here! To celebrate (and because it has become a bit of a tradition on this blog) let’s do a bit of Elvish, shall we?

So, in the High-elven tongue, the sixth month of the year was named Nárië. (Nórui was its Sindarin equivalent.)

Now, the root nár—is a direct reference to the Quenya word for ‘fire’. In fact, one of the Three Elven Rings that Gandalf bore was named Narya (The Ring of Fire).

In this context, however, nár is most likely a reference to the heat of the Sun (which was named Anar in Quenya).

ThusNárië was the month that signified the coming of summer.

Thus May comes to an end …

Speaking of May, did you know that the fifth month of the year was named Lótessë in the High-elven tongue? Lothron was its Sindarin equivalent. Both were derived from the Elvish root loth, meaning ‘flower’, in reference to the blossoming typically associated with this time of year.

As Samwise Gamgee once put it:

In western lands beneath the Sun

the flowers may rise in Spring