#world war one

This WWI portrait comes courtesy of @wherethepoppiesblow:

“It’s my grand uncle Michael L Ryan (right) who served with the 16th bn highland light infantry he was killed in action on the first day of the Somme attacking toward just south of Thiepval. He is with his brother William Patrick Ryan (left) my great grandfather who served in the merchant navy during both wars. He was also killed in action in WW2.”

Thank you for sharing your story and family history, @wherethepoppiesblow.

Post link

A member of the Canadian Cyclist Corp smiles for the camera, September 1917.

Original image source: Canadian Library and Archives

Post link

German soldiers assist members of the Canadian Medical Corp in transporting Canadians injured in the battle of Vimy Ridge. April 1917.

Original image source: Canadian Library and Archives

Post link

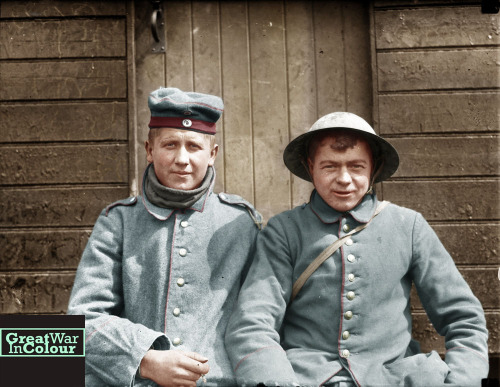

Two German prisoners of war captured by Canadians during the Battle of Vimy Ridge.

Original image source: Library and Archives Canada

Post link

Canadian soldiers in a reserve trench, during the battle of the Somme, watch shrapnel bursts above them.

Original image source: Library and Archives Canada

Post link

Meet the bird that captured the heart of this Canadian soldier… and maybe some of his things.

The four photographs below show a jackdaw who was found sometime during the Battle of the Somme. It became the mascot of this Canadian Army Service Corp despite the fact that he was a bit of thief and “continually stealing” from them. The pictures below were taken in March, 1917.

Photographs:1,2,3,4 from the Canadian Library and Archives.

Looking for more photographs of animals at war? Check out the Atlantic’sphoto series on the very topic.

Taking a break from colourizing, GWIC Takes Five is a feature which brings to you primary source material from the First World War. Whether it be postcards, posters, or letters. To see more, track the tag GWIC Takes Five.

October 18 1921, Washington–Despite multiple attempts, the Treaty of Versailles had failed to reach the required two-thirds majority for ratification in the US Senate. The Harding Administration negotiated and signed new treaties with Germany, Austria, and Hungary, dropping American participation in the League of Nations or most other international commitments from Treaty of Versailles. Nonetheless, there was still determined opposition to the new treaties, and it was no means clear that the new treaties would not meet the same fate. Wilson, now living in DC, attempted to organize Democrats against the treaty, while a few die-hard irreconcilables opposed the treaty as they feared any recognition of any aspect of the Treaty of Versailles would lead to the United States joining the League of Nations in the future. Ultimately, however, the treaty with Germany was ratified by a wide margin, 66-20, with more than half of the Senate Democrats voting in favor. The other treaties were ratified by a similar margin. Wilson, fuming at this final defeat, called the treaty’s supporters “the most partisan, prejudiced, ignorant, and unpatriotic group that ever misled the Senate of the United States.”

A massive crowd rallies outside the former Royal Palace and the Kaiser Wilhelm Monument, expressing their support for the Republic. Both structures were demolished by the East German government after World War II, though a reconstruction of the palace was completed in 2020.

August 31 1921, Biberach–Matthias Erzberger, leading advocate of peace since July 1917 and signer of the Armistice, quickly became a bête noire to the German right, who viewed him as a traitor. By 1921, he had retreated to the backbenches of the Reichstag. Organisation Consul, a violently anti-Semitic and ultranationalist terror group formed after the dissolution of the Ehrhardtbrigade (the main force behind last year’s Kapp Putsch), assassinated Erzberger on August 26. The two assassins escaped Germany and would not stand trial until after World War II.

His funeral, on August 31, became a political rally for his Zentrumparty; the keynote speaker was his long-time ally, Chancellor Joseph Wirth. In Berlin, over 100,000 workers, mostly members of the SDP and other left-wing parties, demonstrated in support of the fragile German Republic.

May 26 1921, Oppeln [Góra Świętej Anny]–The Polish and French had attempted to prevent Freikorps from reaching Upper Silesia, but were only able to delay them by a few weeks. On May 21, the Germans launched an attack on the Annaberg hill, which dominated the surrounding Oder valley. They were able to take the hill and hold it against Polish counterattacks, but a lack of artillery prevented them from pushing much beyond it. The Poles officially abandoned their efforts to retake the hill on May 26, and fighting only continued on a limited basis for the next month. The final division of Upper Silesia would largely follow the German-Polish lines after the battle.

IRA Burns Dublin Custom House

The Customs House on fire.

May 25 1921, Dublin–Fighting during the Irish War of Independence had so far been on a smaller scale: ambushes, assassinations, and the like. Éamon De Valera, President of the Dáil, pushed strongly for a higher-profile engagement, over Michael Collins’ objections. At 1 PM on May 25, the IRA stormed the Custom House in Dublin and began making preparations to burn the building. However, before they could finish and evacuate the building, British Auxiliaries arrived and began firing at the IRA inside, who quickly set the building on fire. The IRA quickly ran out of ammunition and could not hold out for long in a burning building, and at least 80 IRA members were arrested. Fire brigades were also held up by the IRA and arrived too late to save the building, which burned to the ground. The Irish tried to claim the burning of the Custom House as a propaganda victory, but the capture of so many men was a serious blow.

This took place against the backdrop of the previous day’s elections, called for in both Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland by the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which had first formalized the partition of the island. Apart from the four seats reserved for Trinity College, the Southern Irish seats were uncontested and swept by Sinn Féin, who would not take their seats in a parliament they had not agreed to and did not recognize. In the north, the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) took two-thirds of the vote and three-quarters of the seats, with the remainder split between Sinn Féin and the remnants of the Irish Parliamentary Party. The Government of Ireland Act 1920 had not included all of Ulster to secure such a Unionist majority in the north, but had also included a large Catholic minority simply to give Northern Ireland a larger region on the map.

Sources include: Michael Hopkinson, The Irish War of Independence.

Poles Seize Portions of Silesia

Polish paramilitaries with a derailed train during the uprising.

May 3 1921, Katowice–The Upper Silesian plebiscite in March had retuned a solid majority for Germany over Poland. Unlike most other post-war plebiscites, however, the plebiscite results did not immediately determine the border, but would instead be used by the Allies to guide the drawing the border. This left a lot of room for interpretation, with the French wanting to assign most of the highly-industrialized parts of Silesia to their Polish allies, but the British wanting them assigned to Germany to make sure the German economy could afford to pay war reparations to Britain.

As April progressed, the Poles feared that the British position would prevail at the negotiations, and they began to plan to force a fait accompli on the ground. On the night of May 2-3, Polish special forces destroyed all the rail connections between the area and the rest of Germany, and the next day Polish paramilitaries moved in and seized control of much of the disputed area. There were Allied troops in the area, but French forces were largely content to give the Poles free rein, while the British and Italians could only offer limited support to the Germans; no concerted effort was made to stop the fighting or get the Poles to withdraw

The destruction of the rail bridges, and a French decree against the arrival of paramilitaries from the rest of Germany, made it difficult for German reinforcements to arrive (or for reprisals to be carried out against the local Polish population), but Freikorpsmembers trickled into the area nonetheless over the next few weeks.

Fascist Violence in Bolzano

April 24 1921, Bolzano—Despite firm prohibitions from the Allies on Austria joining Germany, the idea remained quite popular there. On April 24, despite no official recognition from the Austrian government (let alone the Allies), the portions of Tyrol remaining in Austria held a plebiscite on becoming part of Germany, and the vote was overwhelmingly in favor of the idea. Nothing would become of this (nor a similar vote in Salzburg in May) until the 1938 Anschluss.

South Tyrol, on the other hand, was now part of Italy, despite a majority-German population. They did not take part in the plebiscite, but Italian fascists saw the opening of the Bolzano Spring Fair that same day, complete with a parade in traditional German costumes, as part of the same movement. On that morning, local fascists joined with others who arrived by train and attacked the parade, killing one and injuring fifty. Only two fascists were arrested, and they would be released within a week after a threat of further violence from Mussolini, who was the undisputed leader of the extreme right since D’Annunzio’s ignominious expulsion from Fiume in December 1920.

April 2 1921, Yerevan–TheSoviets took over most of Armenia in December 1920, seeming a better alternative to the approaching Turkish armies. Soviet control was short-lived, after the Soviets quickly alienated much of the population, the Dashnaks were able to retake Yerevan and much of the surrounding area in mid-February. After conquering Georgia and negotiating a peace treaty with the Turks in March, the Soviets were once again able to concentrate on Armenia, launching an offensive on March 24 and retaking Yerevan on April 2. The Dashnaks fell back into the mountains in the Syunik province, where they continued to fight against the Soviets until July.

A Belarusian cartoon lamenting the partition of Belarus between the Soviets and the Poles in the Treaty of Riga; note that the original Soviet proposals would have placed MInsk (center) on the Polish side.

March 18 1921, Riga–The Soviets and Poles had concluded an armistice in October, but a formal peace treaty had proved elusive. The Soviets, eager to normalize their relations with their neighbors, were fine with drawing the border roughly along the armistice line. Many of the Polish negotiators, however, did not want to annex so much eastern territory whose inhabitants were mostly Belarusians and Ukrainians, and the Polish delegation rejected the offer, much to Piłsudski’s chagrin.

By March, Lenin, who had other more pressing internal concerns with Kronstadt, strikes, and peasant unrest, pressed for a resolution to the negotiations, and on March 18 a treaty was signed in Riga. A border was agreed to about 60 miles west of the original Soviet proposal (but still around 150 miles east of the modern Polish frontier). Most notably, this meant that Minsk would return to Soviet hands. Poland would also receive 30 million rubles in compensation for Russia’s hundred-year occupation of the country.

Soviet and Turkish signatories of the Treaty of Moscow.

March 16 1921, Moscow–TheSoviet invasion of Georgia brought Soviet Russia into direct contact with Turkey, which soon thereafter invaded the country from the south. The Soviets had already repudiated the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk that had given up large areas to the Ottoman Empire. Kemal’s government in Ankara wanted to keep these gains, but was also diplomatically isolated and was more worried about the Allies occupying Constantinople and Smyrna.

On March 16, representatives from Kemal’s government and the Soviets signed a treaty in Moscow. Turkey got to keep most of the gains from Brest-Litovsk, with the exception of Batum [Batumi], while Turkey recognized the Soviet republics in Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. Both sides repudiated Brest-Litovsk and Sèvres, and the question of navigation of the Straits was deferred to a later time. Residents of the territories Russia gave up in Brest-Litovsk were to have the right to leave Turkey with their property intact. Azerbaijan’s control over the Nakhchivan exclave, which continues to this day, was confirmed by both sides.

The treaty brought an end to Turkey’s adventures in the Caucasus (for many decades), and the borders established by the treaty remain largely unchanged to this day. The last organized Georgian resistance to the Soviet invasion collapsed two days after the treaty, leaving the Soviets free to concentrate on the Dashnaks in Armenia.

Sources include: Evan Mawdsley, The Russian Civil War

“Battle of Bailleul. Men of the Middlesex Regiment holding a street barricade in Bailleul, 15 April 1918, just before the fall of the town.“ Taken by photographer John Warwick Brooke.

Source: Imperial War Museum.

Post link

“Battle of Pozieres Ridge. Troops of the 1st Australian Division (1st ANZAC Corps), some wearing German helmets, photographed between La Boisselle and Pozieres on their return from the taking of Pozieres, 23 July 1916.” By John Warwick Brooke.

Source: Imperial War Museum.

Post link

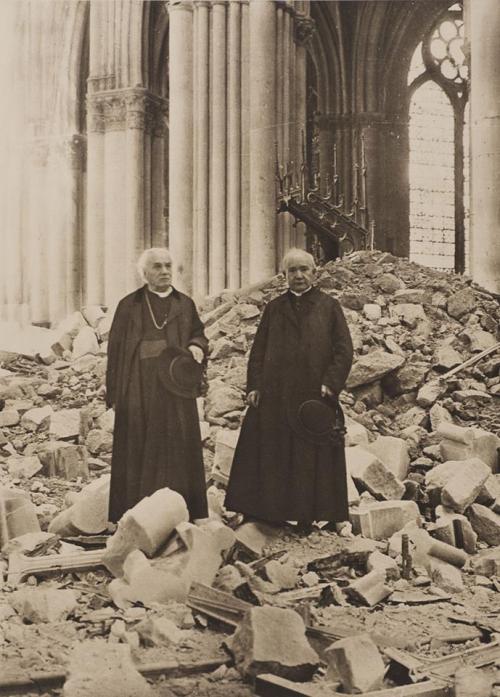

Reims after the First World War (1914-1918).

Notre-Dame de Reims après les bombardements de 1914-1918.

Post link

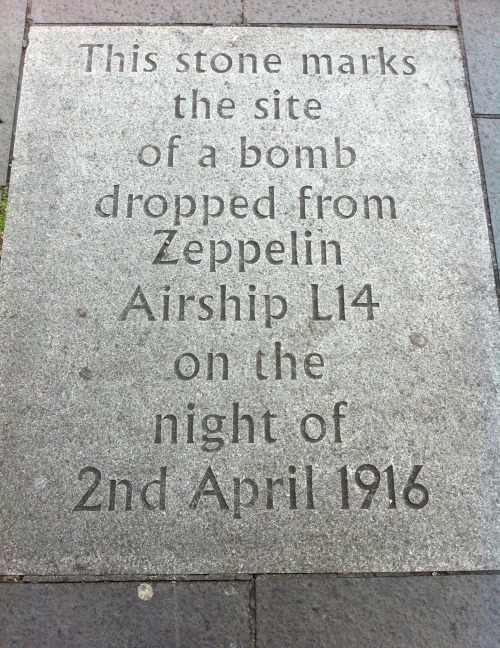

Centenary of Edinburgh Zeppelin Raid

Tonight marks 100 years since two Imperial German Zeppelins attacked Edinburgh and Leith resulting in the deaths of 13 people and injuring 24 others.

On the night of the 2nd April, 1916 four Zeppelins set out from the German Naval Airbase base of Nordholz with the intention to find and destroy targets of interest in and around the Firth of Forth especially the large Naval facilities of Rosyth. One of the Zeppelins, L13 was forced to turn back due to technical difficulties whilst L16 made an abortive journey to Northumberland.

The remaining two Zeppelins: L14 and L22 approached Leith and Edinburgh. L22 caused minor damage to Edinburgh having jettisoned much of its payload in open country near Berwick-Upon-Tweed. L14 however made a sustained attack on both Leith and the Scottish Capital. In Leith nine high-explosive bombs and eleven incendiary bombs were dropped on the town destroying several houses, businesses and warehouses. One man and a baby were killed.

L14 then continued on to Edinburgh were a further 18 high-explosive bombs and six incendiary bombs were dropped killing 11 people and injuring a further 24 others. Four houses, three hotels and a spirits store were severely damaged with Princes Street station and several other building sustaining lighter damage.

The images included are as follows:

i – The memorial pavement stone situated in the centre of Grassmarket in front of the White Hart Inn which was devastated in the 2nd April raids.

ii – The devastated Grassmarket buildings which includes the White Hart Inn.

iii – A close up of the White Hart Inn.

iv – Zeppelin L14

Post link

A painting showing WW1 Imperial German Askari charging forward.

The German empire recruited natives from German East Africa (now Tanzania) to serve in the Askari units.

They were commanded by European officers, and fought a highly effective campaign against the Allied forces in Africa, fighting against a much larger British force until the end of the war in 1918.

Askari units were all given a army pension, but due to the turmoil at the end of the war this was never carried through. In 1964, the Federal German government attempted to make good on these promises and pay the entire back-log of payments to any surviving Askari who could be found.

A payment station was set up for the men to travel to, seeing as postage to the many unnamed villages was unfeasible. 350 men turned up, but many had lost the papers issued to them at the end of the great war. The banker who had brought the money came up with a simple way to sort the real soldiers from fakes. As each man stepped forward he was handed a broom handle and asked (in German) to perform rifle drill movements with it. Not one man failed the test.

Post link