#xx century

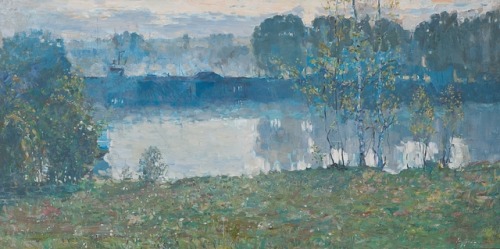

Vyacheslav Fyodorov. Fog.

1970s. Museum of Russian Impressionism, Moscow.

Vyacheslav Fyodorov considered Konstantin Korovin, Vasily Polenov and Alexei Savrasov as his teachers, yet the real school which formed and shaped his talent was that of nature itself. Landscape became almost the only genre in which he worked, and whenever he went out into the open air, he could create dozens of versions of the same view. He did not change anything in the details of composition, instead his goal was to capture the fleeting nuances of the ever-changing scene. The great Claude Monet worked in the same way, time and again re-creating his Rouen Cathedral or Westminster Abbey. Fyodorov pursued the same objective when creating “Fog”. Look closely at his colourful transitions to the heavy vibration of the moist air over the river, at the birch reflections in the water, and the depth of the compelling pattern of the blue morning mist in May.

Post link

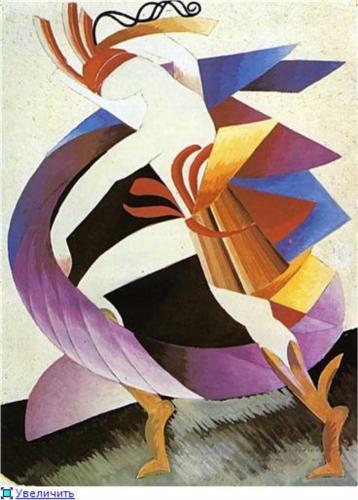

Anton Lavinsky. Poster for Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin.

1925. Chrome lithograph. Production of the 3rd Factory of Goskino. State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg.

Poster for the film ‘The Battleship Potemkin’, 1926, directed by Sergei Eisenstein. Sergei Eisenstein was a Soviet film director and film theorist, a pioneer in the theory and practice of montage. 'The Battleship Potemkin' presents a dramatized version of the mutiny that occurred in 1905 when the crew of the Russian battleship Potemkinrebelled against their officers.

The Russian battleship Potemkin was a pre-dreadnought battleship built for the Imperial Russian Navy’s Black Sea Fleet. It became famous when the crew rebelled against the officers in June 1905 (during that year’s revolution), which is now viewed as a first step towards the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Post link

Valentin Serov. Peter I The Great.

1907. State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

Peter I, or Peter the Great (1672-1725), was one of the most outstanding rulers and reformers in Russian history. He was at first a joint ruler with his weak and sickly half-brother, Ivan V, and his sister, Sophia. In 1696 he became a sole ruler. Peter I was Tsar of Russia and became Emperor in 1721. As a child, he loved military games and enjoyed carpentry, blacksmithing and printing.

Peter I is famous for carrying out a policy of ‘westernization’and drawing Russia further to the East that transformed Russia into a major European power. Having travelled much in Western Europe, Peter tried to carry western customs and habits to Russia. He introduced western technology and completely changed the Russian government, increasing the power of the monarch and reducing the power of the boyars and the church. He reorganized Russian army along Western lines.

He also transferred the capital to St. Petersburg, building the new capital to the pattern of European cities.

In foreign policy, Peter dreamt of making Russia a maritime power. To get access to the Black Sea, the Caspian Sea, the Azov Sea and the Baltic, he waged wars with the Ottoman Empire (1695—1696), the Great Northern War with Sweden (1700-1721), and a war with Persia(1722-1723). He managed to get the shores of the Baltic and the Caspian Sea.

In his day, Peter I was regarded as a strong and brutal ruler. He faced much opposition to his reforms, but suppressed any and all rebellion against his power. The rebellion of streltsy, the old Russian army, took place in 1698 and was headed by his half-sister Sophia. The greatest civilian uprising of Peter’s reign, the Bulavin Rebellion (1707—1709) started as a Cossack war. Both rebellions aimed at overthrowing Peter and were followed by repressions.

Peter I played a great part in Russian history. After his death, Russia was much more secure and progressive than it had been before his reign.

Post link

Stanislav Zhukovsky. Interior of a Room.

1910-20s. Museum of Russian Impressionism, Moscow.

Apparently, this painting of Stanislav Zhukovsky was inspired by memories of his distant childhood. The son of a Russian aristocrat who had lost his family estate, the artist often addressed the theme of the ancestral estates of the nobility, with their spacious rooms, elegant decor, and parks. “I’m a great fan of antiquities, and, in particular, of Pushkin’s epoch …” – Zhukovsky used to say about himself. And this interior is a return to the past, too. The room is filled with life, light and air - every object, whether vase, chair or portrait, seems to convey an emotion of its own. And what an idyllic vista opens up outside the window! However, Stanislav Zhukovsky would pay a bitter price for his passion for the old. He was a popular artist and a participant in the best exhibitions, but after the Revolution all of a sudden, he became an “enemy of the Proletariat”. The press called this poet of the past noble era “a living corpse”. His art was compared to a ‘street fairy, or a faded beauty with a rouge on her cheeks and bright lips’. No surprise then that the artist decided to leave for Poland, his historical homeland.

Post link

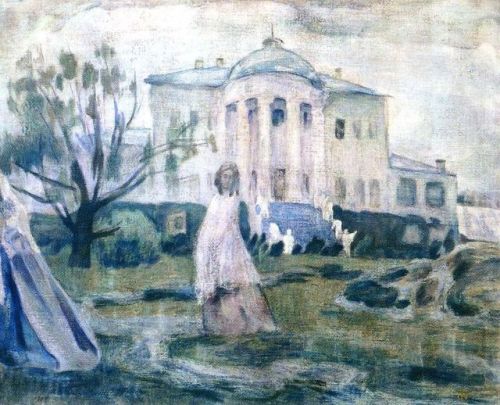

Viktor Borisov-Musatov. Ghosts.

1903. State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

The image of the world in the picture is represented using a fine, semi-transparent veil, which seems to conceal strange light. Phantom figures, generating numerous reflections in the wave-like fluctuations of space, glide away like echoes of music that is dying in the distance. By placing the figures in no particular order, the artist creates an impression of their spontaneous movement, as if they were driven by some unknown force pushing them. The image instability is achieved using the technique of reduced dull tempera to produce fresco-like radiance. The picture seems to comprise quite a few transparent layers. The colours do not obscure the view of the underlying fabric of coarse-grained canvas, which produces the effect of material half decomposed with time. The painting becomes so immaterial that it comes close to poetry and music.

Post link

Anatoly Shepelyuk. M.I. Kutuzov at the command post on the day of the Battle of Borodino. (Left)

1951.

Vasily Vereshchagin. Napoleon Near Borodino. (Right)

1897. Museum of Patriotic War of 1812, Moscow.

TheFrench invasion of Russia, known in Russia as the Patriotic War of 1812, and in France as the Russian Campaign, began on 24 June 1812 when Napoleon’s Grande Armée crossed the Neman River in an attempt to engage and defeat the Russian army. Napoleon hoped to compel Tsar Alexander I of Russia to cease trading with British merchants through proxies in an effort to pressure the United Kingdom to sue for peace. The official political aim of the campaign was to liberate Poland from the threat of Russia.

The campaign was a turning point in the Napoleonic Wars. The reputation of Napoleon was severely shaken, and French hegemony in Europe was dramatically weakened. The Grande Armée, made up of French and allied invasion forces, was reduced to a fraction of its initial strength. These events triggered a major shift in European politics. France’s ally Prussia, soon followed by Austria, broke their imposed alliance with France and switched sides. This triggered the War of the Sixth Coalition.

TheBattle of Borodino was a battle fought on 7 September 1812. Although the Battle of Borodino can be seen as a victory for Napoleon, some scholars and contemporaries described Borodino as a Pyrrhic victory for the French, which would ultimately cost Napoleon the war and his crown, although at the time none of this was apparent to either side.

This victory ultimately cost Napoleon his army, as it allowed the French emperor to believe that the campaign was winnable, exhausting his forces as he went on to Moscow to await a surrender that would never come. The Borodino victory allowed Napoleon to move on to Moscow, where — even allowing for the arrival of reinforcements — the French Army only possessed a maximum of 95,000 men, who would be ill-equipped to win a battle due to a lack of supplies and ammunition. The Grande Armée suffered 66% of its casualties by the time of the Moscow retreat; snow, starvation, and typhus ensured that only 23,000 men crossed the Russian border alive. Furthermore, while the Russian army suffered heavy casualties in the battle, they had fully recovered by the time of Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow; they immediately began to interfere with the French withdrawal, costing Napoleon much of his surviving army.

Post link

A Young Man Breaking into the Girls Dance, and the Old Women are in Panic - Andrei Ryabushkin, 1902

Post link

Hace un par de semanas, me uní a un grupo nuevo en la ciudad que recrean principios del siglo XX. Aprovechamos el tiempo soleado que aún hacia para dar una vuelta y disfrutar porque tal vez la que sea la primera y última quedada de este año.

Post link