#roman sculpture

MWW Artwork of the Day (4/6/16)

Late Imperial Period (Roman, 3rd-5th c. CE)

Triumph of Dionysos and the Seasons (c. 260–70 CE)

Marble sarcophagus relief sculpture, 86.4 x 215.9 x 92.1 cm.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Joseph Pulitzer Bequest)

This highly ornate and extremely well-preserved Roman marble sarcophagus came to the Metropolitan Museum from the collection of the dukes of Beaufort and was formerly displayed in their country seat, Badminton House in Gloucestershire, England. An inscription on the unfinished back of the sarcophagus records that it was installed there in 1733. In contrast to the rough and unsightly back, the sides and front of the sarcophagus are decorated with forty human and animal figures carved in high relief. The central figure is that of the god Dionysos seated on a panther, but he is somewhat overshadowed by four larger standing figures who represent the four Seasons (from left to right, Winter, Spring, Summer, and Fall). The figures are unusual in that the Seasons are usually portrayed as women, but here they are shown as sturdy youths. Around these five central figures are placed other Bacchic figures and cultic objects, all carved at a smaller scale. On the rounded ends of the sarcophagus are two other groups of large figures, similarly intermingled with lesser ones. On the left end, Mother Earth is portrayed reclining on the ground; she is accompanied by a satyr and a youth carrying fruit. On the right end, a bearded male figure, probably to be identified with the personification of a river-god, reclines in front of two winged youths, perhaps representing two additional Seasons.

The sarcophagus is an exquisite example of Roman funerary art, displaying all the virtuosity of the workshop where it was carved. The marble comes from a quarry in the eastern Mediterranean and was probably shipped to Rome, where it was worked. Only a very wealthy and powerful person would have been able to commission and purchase such a sarcophagus, and it was probably made for a member of one of the old aristocratic families in Rome itself. The subjects – the triumph of Dionysos and the Seasons – are unlikely, however, to have had any special significance for the deceased, particularly as it is clear that the design was copied from a sculptor’s pattern book. Another sarcophagus, now in the Hessisches Landesmuseum in Kassel, Germany, has the same composition of Dionysos flanked by the four Seasons, although the treatment and carving of the figures is quite different. On the Badminton sarcophagus the figures are carved in high relief and so endow the crowded scene with multiple areas of light and shade, allowing the eye to wander effortlessly from one figure to another. One must also imagine that certain details were highlighted with color and even gilding, making the whole composition a visual tour de force.

Very few Roman sarcophagi of this quality have survived. Although the Badminton sarcophagus lacks its lid, the fact that it was found in the early eighteenth century and soon thereafter installed in Badminton Hall means that it has been preserved almost intact and only a few of the minor extremities are now missing.

(from the MMA catalog)

For more Roman sculpture, visit this MWW Special Collection:

* MWW Ancient/Medieval Art Gallery

Post link

The so-called Psyche di Capua (actually a Venus), is a statue found in 1726 in the Campano amphitheater in Santa Maria Capua Vetere, where it decorated the front porch of the summa cavea together with other sculptures.

Napoli, Museo Archeologico Nazionale

Photo: Luigi Spina

Post link

Statua femminile di Concordia

I sec. d.C.

Napoli, Museo Archeologico Nazionale

Photo: © Luigi Spina

Post link

Flora Farnese

Roman marble sculpture based on a Greek model from the 5th century BC

2nd century AD

Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli

© Ph. Luigi Spina

Post link

Afrodite Sosandra

Roman marble copy of an original attributed to the Greek sculptor Calamis (ca. 460 BC).

2nd century AD

National Archeological Museum, Naples

© Ph. Luigi Spina

Post link

On this day (14 September) in 81 A.D., Domitian became Roman Emperor. The last member of the Flavian dynasty, Domitian (Caesar Domitianus Augustus) was the second son of Emperor Vespasian and brother to the Emperor Titus, whom he succeeded when the latter died unexpectedly from a fever.

Prior to taking the imperial throne, Domitian had acted as a praetor (a judicial officer) and was appointed as consul on six separate occasions.

According to the Roman historian Suetonius, Domitian (as a young aristocrat) possessed a “lawless” streak that foreshadowed his reign, which would ultimately be remembered mainly for the Emperor’s cruelty and viciousness.

Suetonius however, also informs his readers that there were many positive aspects to Domitian’s rule. He “presented many extravagant entertainments in the Colosseum and the Circus… nor did he ever forget the Games given by the quaestors.” The Emperor also “founded a threefold festival of music,” dedicated to the Capitoline Jupiter. Domitian additionally embarked on a programme to restore some of Rome’s most important buildings, while adding to the city’s architecture with new construction projects. These ventures included, “a temple to Jupiter the Guardian on Capitoline Hill, the Forum of Nerva, the Flavian Temple, a stadium, a concert hall and [an] artificial lake for sea-battles.”

In the theatre of war, Domitian also led various campaigns: some that were perceived as justified and others, which were considered unnecessary. For instance, Suetonius calls the conflict against theChatti, “uncalled for” and the war against the Sarmatians, justified.

The Roman historian also claimed that “Domitian made a number of social innovations.” These included cancelling the public grain issue, banning castration and increasing the number of official chariot teams from four, to six.

Conversely, Domitian’s cruelty was infamous and well-reported. Suetonius divulges that “he executed [a] beardless boy, in distinctly poor health, merely because he happened to be a pupil of the actor Paris.” When the emperor disagreed with the writings of Hermogenes of Tarsus, the Greek rhetorician was executed and “the slaves who had acted as copyists were crucified.” Members of Roman civic society also lost their lives during Domitian’s reign of fear. Suetonius reveals that Civica Cerealis, Acilius Glabrio and Salvidienus Orfitus were “accused of conspiracy” and summarily executed. Aelius Lamia however, was killed because he voiced a sarcastic comment and Salvius Cocceianus “died because he continued to celebrate the birthday of the Roman Emperor Otho.”

Consequently, Domitian’s cruelty and autocracy earned him the disdain of the senate and he was assassinated on 18 September, 96 A.D.

References: Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, trans. Robert Graves, revised with an introduction by Michael Grant, London: Penguin Books, 1979, pp. 303-319.

Images:Statue of Emperor Domitian, 1st Century A.D., marble, Vatican Museums, Vatican City, Rome. Wikimedia Commons.

Bust of Domitian, 1st Century A.D., marble, Musée du Louvre, Paris. Wikimedia Commons.

A Denarius of Domitian. Wikimedia Commons.

A Sestertius of Domitian. Wikimedia Commons.

Statue of the Roman Emperor Domitian, Vaison-la-Romaine, France. Wikimedia Commons.

Post link

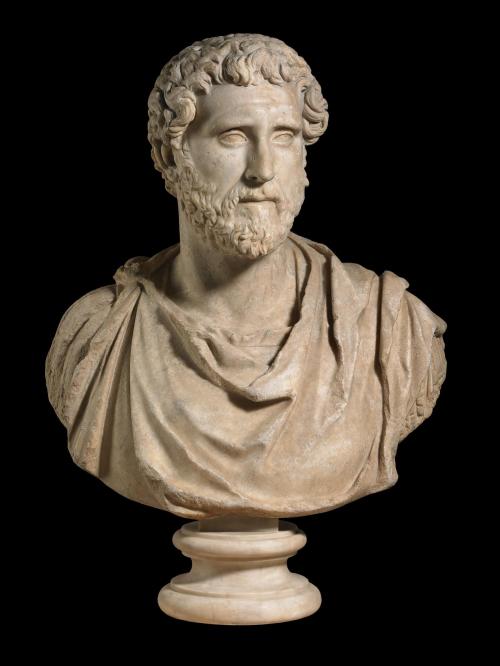

A bust of Emperor Antoninus Pius wearing military dress, from the early years of his reign c. 140

Image from the National Museums Scotland via their online collection:IL.2008.64.1

Post link

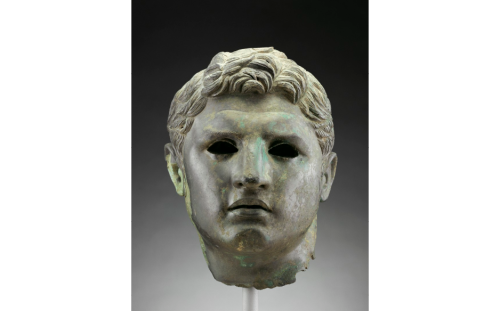

Clipeus with Bust of Nike Roman 25 B.C.E.-25 C.E.bronze

Eagle Roman Asia Minor 100-300 C.E.

Portrait of a Man Roman Asia Minor 1rst Century B.C.E.

Post link

Day One | Antiquity | Art History Post Prompt

Aphrodite, otherwise known as the Crouching Venus, is Roman marble sculpture created during the Antonine period (second century AD). This piece in particular is a Roman copy of the Hellenistic original, created in 200 BC.

Among the many, many October prompt lists for artists, I thought it’d be fun to adapt one I found for Art History post purposes. I have found one from @avacairen (twitter) from 2018 but, hey, it works. Here we have Day 1: Antiquity.

Post link

Portrait head of Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (called Caracalla), ca. 217–230; Late Severan

Post link

Roman Sculpture of the Three Graces, 2nd century

Marble

Image released into the public domain.

Post link

Just like we talked about in class. These statues look right through you. This creates such an air of importance.. almost divinity. What I really like about Roman sculpture is that you can totally tell the subjects of each sculpture from each other. Even when Romans start adopting a bit of idealism into their sculptures at the cost of hyperrealistic details, I could still tell this sculpture of Augustus easily apart from one of Julius, and Pompey even more so.

Post link

Capitoline Museums - Boy with a Thorn

A Roman bronze sculpture, probably 1st century CE.

Rome, July 2007

Post link

Ares Borghese, imperial era marble, ca. 1st - 2nd century AD, Rome.

The Ares Borghese is a Roman marble statue of the imperial era. It is 2.11m high. It is identifiable as Ares by the helmet and by the ankle ring given to him by his lover Aphrodite. This statue possibly preserves some features of an original work in bronze, now lost, of the 5th century BC. - wikipedia

Post link

LA PORTE NOIRE in Besançon (Latin: Vesontio, later Besontio) is a triumphal arch constructed around AD 175 to commemorate the victories of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus over the Parthians in AD 164/65 and the victories of Marcus Aurelius over various Germanic tribes in AD 171/78.

Called the Arch of Mars in antiquity, the structure was originally free-standing. It was incorporated into the city walls in the Middle Ages and remained engulfed in a bastion until the mid 19th century. The arch ceased to be noire after the restoration of 2011 removed layers of dark soot and debris.

The surviving portion of the unusually rich sculptural decoration depicts the capture of Ctesiphon and scenes of mythogical battles. The reliefs on the other side, now lost, depicted barbarian conquests. The finely-grained, locally-quarried pierre de Vergenne is ideal for detailed carving, but also vulnerable to erosion.

THE FARNESE BULL

Pliny the Elder mentions a sculpture in the collection Asinius Pollio depicting the Supplice of Dirce:

Asinius Pollio, a man of a warm and ardent temperament, was determined that the buildings which he erected as memorials of himself should be made as attractive as possible; for here we see … Zethus and Amphion, with Dirce, the Bull, and the halter, all sculptured from a single block of marble, the work of Apollonius and Tauriscus, and brought to Rome from Rhodes. (Historia Naturalis 36.4)

This outsized Hellenistic sculpture, carved from a single block of marble, was displayed near the Forum in the Atrium Libertatis. In 39 BC, Pollio had funded the rebuilding of this structure, which housed the censor’s archive and the brass tablets of the ager publicus. Also included were an art gallery and Greek and Latin libraries, which Pollio founded in 39 BC. This lavish complex was demolished during the construction of the Forum of Trajan.

In 1546, excavators hired by Paul III working in the palestra of the Baths of Caracalla discovered numerous “beautiful fragments of statues and animals were found that were all in one piece in antiquity,” as a contemporary phrased it. These fragments were immediately identified as the Hellenistic group described by Pliny. This identification was supported by the fact that the baths had been built on the site of the Horti Asiniani, the gardens of Pollio’s estate, to where the sculpture might have been relocated after the closing of the Atrium Libertatis. The sculpture was reconstructed and restored by Michelangelo and installed in the Palazzo Farnese.

It is now, however, thought that the Farnese Bull is a late 2nd-century copy of Pollio’s sculpture. If that is the case, the original was either already lost or at some other location. The decision to place this work in a bathing complex contrasts sharply with the context of Pollio’s version. Situated in the Atrium Libertatis, the sculpture was prized by its owner and his cultured peers for its Greek pedigree, technical virtuosity and mythological drama. The Severans, however, may have chosen it for its size. Rising 4 m from the floor on a 3.3” x 3.3” m base, the Farnese Bull (unlike the other sculptures decorating the main bathing block) held its own amidst the gargantuan architecture. Besides the work’s scale, its violent subject matter and turbulent composition might have appealed to Caracalla’s brutish tastes and personality.

Bust of an ephebe (Narcissus leaning on a pillar)

Marble, Roman copy of a Greek original of the late 5th century BC.

Museo Chiaramonti, Vatican Museums, Rome

Canopo, Villa Adriana, Tivoli