#world war i

May 26 1921, Oppeln [Góra Świętej Anny]–The Polish and French had attempted to prevent Freikorps from reaching Upper Silesia, but were only able to delay them by a few weeks. On May 21, the Germans launched an attack on the Annaberg hill, which dominated the surrounding Oder valley. They were able to take the hill and hold it against Polish counterattacks, but a lack of artillery prevented them from pushing much beyond it. The Poles officially abandoned their efforts to retake the hill on May 26, and fighting only continued on a limited basis for the next month. The final division of Upper Silesia would largely follow the German-Polish lines after the battle.

IRA Burns Dublin Custom House

The Customs House on fire.

May 25 1921, Dublin–Fighting during the Irish War of Independence had so far been on a smaller scale: ambushes, assassinations, and the like. Éamon De Valera, President of the Dáil, pushed strongly for a higher-profile engagement, over Michael Collins’ objections. At 1 PM on May 25, the IRA stormed the Custom House in Dublin and began making preparations to burn the building. However, before they could finish and evacuate the building, British Auxiliaries arrived and began firing at the IRA inside, who quickly set the building on fire. The IRA quickly ran out of ammunition and could not hold out for long in a burning building, and at least 80 IRA members were arrested. Fire brigades were also held up by the IRA and arrived too late to save the building, which burned to the ground. The Irish tried to claim the burning of the Custom House as a propaganda victory, but the capture of so many men was a serious blow.

This took place against the backdrop of the previous day’s elections, called for in both Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland by the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which had first formalized the partition of the island. Apart from the four seats reserved for Trinity College, the Southern Irish seats were uncontested and swept by Sinn Féin, who would not take their seats in a parliament they had not agreed to and did not recognize. In the north, the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) took two-thirds of the vote and three-quarters of the seats, with the remainder split between Sinn Féin and the remnants of the Irish Parliamentary Party. The Government of Ireland Act 1920 had not included all of Ulster to secure such a Unionist majority in the north, but had also included a large Catholic minority simply to give Northern Ireland a larger region on the map.

Sources include: Michael Hopkinson, The Irish War of Independence.

Poles Seize Portions of Silesia

Polish paramilitaries with a derailed train during the uprising.

May 3 1921, Katowice–The Upper Silesian plebiscite in March had retuned a solid majority for Germany over Poland. Unlike most other post-war plebiscites, however, the plebiscite results did not immediately determine the border, but would instead be used by the Allies to guide the drawing the border. This left a lot of room for interpretation, with the French wanting to assign most of the highly-industrialized parts of Silesia to their Polish allies, but the British wanting them assigned to Germany to make sure the German economy could afford to pay war reparations to Britain.

As April progressed, the Poles feared that the British position would prevail at the negotiations, and they began to plan to force a fait accompli on the ground. On the night of May 2-3, Polish special forces destroyed all the rail connections between the area and the rest of Germany, and the next day Polish paramilitaries moved in and seized control of much of the disputed area. There were Allied troops in the area, but French forces were largely content to give the Poles free rein, while the British and Italians could only offer limited support to the Germans; no concerted effort was made to stop the fighting or get the Poles to withdraw

The destruction of the rail bridges, and a French decree against the arrival of paramilitaries from the rest of Germany, made it difficult for German reinforcements to arrive (or for reprisals to be carried out against the local Polish population), but Freikorpsmembers trickled into the area nonetheless over the next few weeks.

Fascist Violence in Bolzano

April 24 1921, Bolzano—Despite firm prohibitions from the Allies on Austria joining Germany, the idea remained quite popular there. On April 24, despite no official recognition from the Austrian government (let alone the Allies), the portions of Tyrol remaining in Austria held a plebiscite on becoming part of Germany, and the vote was overwhelmingly in favor of the idea. Nothing would become of this (nor a similar vote in Salzburg in May) until the 1938 Anschluss.

South Tyrol, on the other hand, was now part of Italy, despite a majority-German population. They did not take part in the plebiscite, but Italian fascists saw the opening of the Bolzano Spring Fair that same day, complete with a parade in traditional German costumes, as part of the same movement. On that morning, local fascists joined with others who arrived by train and attacked the parade, killing one and injuring fifty. Only two fascists were arrested, and they would be released within a week after a threat of further violence from Mussolini, who was the undisputed leader of the extreme right since D’Annunzio’s ignominious expulsion from Fiume in December 1920.

April 2 1921, Yerevan–TheSoviets took over most of Armenia in December 1920, seeming a better alternative to the approaching Turkish armies. Soviet control was short-lived, after the Soviets quickly alienated much of the population, the Dashnaks were able to retake Yerevan and much of the surrounding area in mid-February. After conquering Georgia and negotiating a peace treaty with the Turks in March, the Soviets were once again able to concentrate on Armenia, launching an offensive on March 24 and retaking Yerevan on April 2. The Dashnaks fell back into the mountains in the Syunik province, where they continued to fight against the Soviets until July.

March 27 1921, Budapest–The Romanians, after their successful invasion, had allowed monarchists to take over the government in Hungary. Many Hungarian monarchists were still loyal to the Habsburgs, but the Allies and Hungary’s neighbors were adamant that neither former Emperor Charles nor any other Habsburg would be allowed to rule in Hungary. As a result, when the monarchy was officially restored in March 1920, there was no monarch, and Horthy was declared Regent.

Charles wanted to return and claim the throne, and believed he would have support from the Hungarian people and French PM Briand, while Hungary’s neighbors would not again intervene in an internal Hungarian matter. He shaved his mustache and arrived in Hungary on March 26, hoping that the Easter holidays would smooth his return to the throne. The next day, Easter Sunday, Charles met with Hungarian PM Teleki near the Austrian border early in the morning. Teleki told Charles he had come back “too soon, too soon” and that he should head back to Switzerland; an attempt to claim the throne now could lead to civil war and another round of invasions.

Undeterred, Charles proceeded to Budapest to meet with Horthy, dragging him away from his Easter dinner. Teleki’s car conveniently made a wrong turn on the way, and he was not present at the meeting. Charles attempted to appeal to Horthy’s oaths he had taken to him personally as his Emperor, and while this did have an effect, he reminded Charles that he had also sworn an oath to the nation of Hungary. Horthy eventually gave Charles three weeks to leave Hungary, whether to return back to Switzerland or to attempt to claim the Austrian throne in Vienna. Charles incorrectly interpreted this as Horthy telling him he would try to arrange his restoration to the throne within three weeks.

Over the coming days, it became clear that Charles’ optimism was ungrounded; the Czechs and Yugoslavs threatened war if he were restored, the Hungarian Diet voted in favor of Horthy’s continuation as Regent, and Briand refused to offer any support; Charles returned to Switzerland, defeated, on April 5.

A map of the plebiscite results, with red areas voting for Poland and gray areas voting for Germany. Complicating a division of the region was the fact that many of the towns in the east had large German majorities, but were surrounded by Polish-majority countryside.

March 20 1921, Opole–TheTreaty of Versailles called for a plebiscite in Upper Silesia to decide on the final border between Germany and Poland in that economically-valuable region. Allied troops had been sent to the area to administer the plebiscite and to attempt to keep the various German and Polish paramilitary forces in the area under control; a recent need for British reinforcements had precluded British participation in the occupation of Düsseldorf. One concession the Germans had won in the negotiations in Paris was the right of anyone born in the area to return for the plebiscite, even if they had left decades ago, and multiple German trains brought in such eligible voters.

The vote was held on March 20, and the results featured a substantial lead for Germany, 59.6 - 40.4%, out of over a million votes cast. However, unlike in other plebiscites, where a vote in a pre-defined region meant that the region would join one country or another, the results of the vote in each commune were to be used as input in the drawing of the border (along with “geographical and economic conditions”). Quickly, it became apparent that the French favored a final border far more favorable to Poland than the British did, so the plebiscite did not resolve much by itself.

Sources include: Margaret MacMillan, Paris 1919. Image Credit: Leo Baeck Institute.

March 19 1921, Crossbarry–The war in Ireland had escalated since Bloody Sunday, but for the most part the pattern in much of the country was occasional ambushes of British troops and police by IRA flying columns, followed by British reprisals. On March 19, the British attempted to reverse this pattern and trap a several IRA columns near Crossbarry, about 12 miles southwest of Cork. The British had learned of their presence from a prisoner captured in a failed train ambush the previous month. Several hundred British troops proceeded to the area by lorry, then began a sweep on foot and by bicycle to lessen their chance of detection; they did manage to kill one IRA officer before the IRA realized what was happening. The IRA, despite only having 104 men, decided to try to fight their way out of the encirclement before the cordon tightened too close, and laid an ambush for one of the approaching British columns.

This ambush was successful, and the IRA then defeated three additional British columns in turn before effecting their escape from the area under fire. Six IRA men were killed; British figures are disputed, but range from ten to thirty. The fighting at Crossbarry was, according to historian Michael Hopkinson, “the closest approximation to a conventional battle in the whole War,” demonstrating the vastly different character of the Irish War of Independence when compared to other European conflicts of the time period.

Sources include: Michael Hopkinson, The Irish War of Independence.

A Belarusian cartoon lamenting the partition of Belarus between the Soviets and the Poles in the Treaty of Riga; note that the original Soviet proposals would have placed MInsk (center) on the Polish side.

March 18 1921, Riga–The Soviets and Poles had concluded an armistice in October, but a formal peace treaty had proved elusive. The Soviets, eager to normalize their relations with their neighbors, were fine with drawing the border roughly along the armistice line. Many of the Polish negotiators, however, did not want to annex so much eastern territory whose inhabitants were mostly Belarusians and Ukrainians, and the Polish delegation rejected the offer, much to Piłsudski’s chagrin.

By March, Lenin, who had other more pressing internal concerns with Kronstadt, strikes, and peasant unrest, pressed for a resolution to the negotiations, and on March 18 a treaty was signed in Riga. A border was agreed to about 60 miles west of the original Soviet proposal (but still around 150 miles east of the modern Polish frontier). Most notably, this meant that Minsk would return to Soviet hands. Poland would also receive 30 million rubles in compensation for Russia’s hundred-year occupation of the country.

The deck of the Petropavlovskafter the defeat of the rebellion.

March 17 1921, Kronstadt [Kotlin]–The failure of the initial attack on Kronstadt was an embarrassment for the Communists, who on the same day convened their Tenth Party Congress in Moscow. On March 10, after Trotsky reported on the situation, 320 delegates volunteered to join the fight. With the spring fast approaching and the ice in the Gulf of Finland threatening to melt, Tukachevsky had to act quickly.

While he prepared another offensive, events moved even quicker at the Congress in Moscow. Lenin had found himself facing direct threats from Kronstadt, strikes in the major cities, and widespread peasant rebellions, along with internal opposition in the form of the Alexander Shliapnikov and Alexandra Kollontai’s Workers’ Opposition. The strikes had largely petered out by mid-March, with promises that trade would resume with the countryside and the food situation would improve. Kronstadt would be crushed by force. The Workers’ Opposition would be effectively dissolved by a ban on internal Communist Party factions, passed without fanfare on April 16 but which would confirm a dictatorship until Gorbachev.

The farmers, Lenin chose to mollify. Food had heretofore been requisitioned from communities in large quantities by the government. This system was to be turned into a tax, 45% lower than the previous rate, and levied on an individual basis. Any remaining food could be sold on the open market, and additional incentives were provided to boost production. What would become the New Economic Policy pleased the farmers who directly benefited, and the city-dwellers whose food worries would be alleviated; it had only taken a betrayal of Communist ideals. Lenin justified this before the Congress on March 15 by saying that an alliance with the peasants was needed if Communism was to survive in a relatively non-industrialized country like Russia without outside help–but after years of war, there was little opposition to a policy that might bring an end to the conflicts.

The announcement of the land tax also boosted the morale of Tukachevsky’s forces, which had also been reinforced with loyal Communists from around the country. He began another bombardment of Kronstadt on the afternoon of the 16th, and his infantry attacked across the ice in the wee hours of the 17th. Casualties were high; over 10,000 (including 15 of the party delegates who had volunteered from Moscow) were felled by the defenders or were lost through holes in the ice. But shortly before midnight, the Communists had captured the Petropavlovskand most of the other rebellious ships. About 8000 of the rebels escaped across the ice to Finland; most of those captured by the Communists were shot or died in a concentration camp on the White Sea.

Sources include: Orlando Figes, A People’s Tragedy; W. Bruce Lincoln, Red Victory.

Soviet and Turkish signatories of the Treaty of Moscow.

March 16 1921, Moscow–TheSoviet invasion of Georgia brought Soviet Russia into direct contact with Turkey, which soon thereafter invaded the country from the south. The Soviets had already repudiated the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk that had given up large areas to the Ottoman Empire. Kemal’s government in Ankara wanted to keep these gains, but was also diplomatically isolated and was more worried about the Allies occupying Constantinople and Smyrna.

On March 16, representatives from Kemal’s government and the Soviets signed a treaty in Moscow. Turkey got to keep most of the gains from Brest-Litovsk, with the exception of Batum [Batumi], while Turkey recognized the Soviet republics in Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. Both sides repudiated Brest-Litovsk and Sèvres, and the question of navigation of the Straits was deferred to a later time. Residents of the territories Russia gave up in Brest-Litovsk were to have the right to leave Turkey with their property intact. Azerbaijan’s control over the Nakhchivan exclave, which continues to this day, was confirmed by both sides.

The treaty brought an end to Turkey’s adventures in the Caucasus (for many decades), and the borders established by the treaty remain largely unchanged to this day. The last organized Georgian resistance to the Soviet invasion collapsed two days after the treaty, leaving the Soviets free to concentrate on the Dashnaks in Armenia.

Sources include: Evan Mawdsley, The Russian Civil War

Soghomon Tehlirian (1896-1960), Talaat’s assassin, pictured in 1921.

March 15 1921, Berlin–The day after Turkey left the war, much of the Young Turk leadership, including Talaat, Djemal, and Enver Pasha, fled Constantinople with German help. In 1919, courts-martial established under Allied pressure in Constantinople sentenced them to death in absentia. Djemal had thence gone to Afghanistan and Enver to Moscow, but Talaat had remained in Berlin, and German authorities had no plans to extradite him to Turkey.

The Armenian nationalist Dashnaks decided to carry out justice for the Armenian Genocide themselves, and ordered assassinations of the leading Young Turks and other major figures deemed responsible for the genocide. On March 15, Soghomon Tehlirian shot Talaat as he exited his house in Charlottenburg. He did not attempt to flee the scene, and was promptly arrested.

At his trial, which included such witnesses as Liman von Sanders, Tehlirian testified:

I do not consider myself guilty because my conscience is clear…I have killed a man. But I am not a murderer.

After an hour’s deliberation, the jury acquitted him.

Sources include: Raymond Kévorkian, The Armenian Genocide.

Allied soldiers on parade in Düsseldorf.

March 8 1921, Düsseldorf–The Treaty of Versailles did not specify the amount Germany would have to pay in war reparations, but deferred the decision on the exact amount until May 1921; in the meantime, Germany would pay 20 billion gold marks and large quantities of coal and chemicals. With that deadline fast approaching, however, no agreement had been reached, or even seemed close; the Allies had proposed a figure of 226 billion gold marks in January, whle the Germans countered with 30 billion.

To back up their demands, on March 8, 15,000 French and Belgian troops occupied Düsseldorf and Duisburg; the British signed off on the operation but only provided a handful of troops themselves. The French claimed that the lowball German figure meant that the “German Government does not wish to fulfill the engagements it assumed in signing the treaty.” German President Ebert understandably protested:

Our opponents in the World War imposed upon us unheard-of demands, both in money and in kind, impossible of fulfillment. Not only ourselves but our children and grandchildren would have become the work-slaves of our adversaries by our signature. We were called upon to seal a contract which even the work of a generation would not have sufficed to carry out.

We must not and we cannot comply with it. Our honor and self-respect forbid it.

With an open breach of the Peace Treaty of Versailles, our opponents are advancing to the occupation of more German territory.

We, however, are not in a position to oppose force with force. We are defenseless….

Fellow-citizens, meet this foreign domination with grave dignity. Maintain an upright demeanor. Do not allow yourselves to be driven into committing ill-considered acts. Be patient and have faith.

Bolshevik forces attack across the ice towards Kronstadt.

March 8 1921, Kronstadt–The call for a partial democratization of the soviets by the sailors of the Kronstadt naval base was treated as a mortal threat to the revolution by the Bolsheviks in Moscow. Trotsky was sent to Petrograd, issued an ultimatum to the sailors, and took whatever family members he could find as hostages. On March 7, Bolshevik artillery began firing on Kronstadt, and on the wee hours of March 8, under cover of a snowstorm, infantry under Tukhachevsky attacked across the ice. It was worried that their loyalty was shaky, so behind them were Cheka and specially-picked units to make sure they did not flee. To the south of the island, artillery from Kronstadt blew holes in the ice and many of the attacking infantry fell into the freezing water. Some reached the island in the north, but were outnumbered and quickly repulsed.

On the morning of March 8th, the fourth anniversary of the start of the February Revolution, the sailors on Kronstadt were able to celebrate a victory over the Bolsheviks. Their own version of Isvestiapulled now punches in a statement that day:

By carrying out the October Revolution the working class had hoped to achieve its emancipation. But the result has been an even greater enslavement of human beings. The power of the monarchy, with its police and its gendarmerie, has passed into the hands of the Communist usurpers, who have given the people not freedom but the constant fear of torture by the Cheka, the horrors of which far exceed the rule of the gendarmerie under tsarism…

Sources include: Orlando Figes, A People’s Tragedy; W. Bruce Lincoln, Red Victory.

March 1 1921, Kronstadt–Aside from the distant reaches of the Far East, the Whites had been defeated, but severe threats to Bolshevik power remained and even intensified. Revolts spread across the countryside after a poor harvest added to years of hardship from Bolshevik grain requisition. In the cities, hunger became a major concern; by late January, the food ration provided to workers in Moscow and Petrograd was down to 1000 calories a day. Large strikes broke out in Moscow on February 21 and Petrograd the next day, calling for the reconvening of the Constituent Assembly, freedom of movement (most critically, the freedom to go into the countryside and trade for food there, a pattern that had become very familiar in Russia and Germany during the war) and other rights that had been denied by the Bolshevik government. The parallels with the final days of the Czar were undeniable.

The unrest soon spread to the Kronstadt Naval Base, whose sailors had been in the vanguard of leftist opposition to the Provisional Government in 1917. On February 28, the crew of Petropavlovsk,historically staunch Bolsheviks, issued a proclamation calling for new elections for the soviets, full political freedoms for workers, peasants, left socialists and anarchists, and allowing peasants to manage their own land as they see fit as long as they do not hire labor. The proclamation was undeniably left-wing (unlike the strikers in the city, they notably did not call for the Constituent Assembly), but was a clear call for democratization of the Soviets (albeit with participation still extending no further right than the left SRs) and an end to the Bolshevik dictatorship.

On March 1, a crowd of 15,000 met in Anchor Square and agreed for new elections to the local Soviet. The Bolsheviks sent Kalinin to try to defuse the situation, but he only attracted jeers. The next day, rightfully worried that the Bolsheviks would quickly try to take action against them, a Revolutionary Committee of five was elected to organize elections and a defense of the island.

Sources include: Orlando Figes, A People’s Tragedy; W. Bruce Lincoln, Red Victory.

Soviet forces on parade in Tblisi on February 25.

February 25 1921, Tblisi–With both AzerbaijanandArmenia now under Soviet control, the the Soviets quickly turned their attention to Georgia, which was still under control of a Menshevik-dominated government. On February 12, local Bolsheviks began attacking the Georgian military. Two days later, Lenin agreed that the Red Army should intervene, after repeated urging from Stalin, himself a Georgian. On February 16, the Red Army crossed into Georgia, and after an intense nine days of fighting, Soviet tanks (captured from the Whites and their British allies earlier in the Civil War) and armored trains broke through the defenses in the heights above Tblisi.

On February 25, the Soviets entered the city and the local Bolsheviks declared the establishment of the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic. The fall of Tblisi did not mark a complete Soviet victory in the Caucasus, however. Georgian forces, although quickly losing cohesion, were falling back towards the coast and Batum [Batumi]. Simultaneously, the Turks had taken advantage of the situation by seizing some disputed border areas, and they had their eyes on Batum as well. Meanwhile, in Armenia, nationalists had revolted against the Soviets and seized control of Yerevan.

The house in Washington DC where Woodrow Wilson lived out his retirement, purchased less than two weeks after the awarding of the Peace Prize.

December 10 1920, Kristiania [Oslo]–The awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize had largely been suspended during the largest war Europe had seen in centuries; the exception being the 1917 prize, which was awarded to the Red Cross. With peace largely concluded in Europe, in December1920 the Nobel committee awarded the 1919 and 1920 prizes. One was given to Léon Bourgeois, first President of the League of Nations and a long-time advocate for an international criminal court and the formation of an organization similar to (if not even broader in scope than) the League. The other was given to President Wilson, for his efforts in the creation of the League. The American ambassador to Norway accepted the prize on his behalf, and read a short statement by Wilson:

In accepting the honor of your award, I am moved by the recognition of my sincere and earnest efforts in the cause of peace, but also by the very poignant humility before the vastness of the work still called for by this cause….

I am convinced that our generation has, despite its wounds, made notable progress, but it is the better part of wisdom to consider our work as only begun. It will be a continuing labor. In the definite course of the years before us there will be abundant opportunity for others to distinguish themselves in the crusade against the hate and fear of war.

To the great disappointment of Wilson (and the world), the United States had not joined the League of Nations, and would never do so; the awarding of the Peace Prize swayed few minds.

The $29,000 in prize money was highly welcome in the Wilson household, and was a not-insubstantial increase to his savings. His term as President would end in a few months without a pension, and his health problems limited his potential to earn an income. Less than two weeks later, Wilson would purchase a house in Washington DC for his retirement–even with the prize money, his friends had to put up two-thirds of the $150,000 purchase price.

Sources include: Barbara O’Toole, The Moralist. Image Credit: By APK - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

Soviet troops entering Yerevan on December 4.

December 2 1920, Yerevan–Since the Turkish invasion in September, the Armenians had repeatedly suffered defeats. By the time a ceasefire was concluded in mid-November, they had lost most of their territory and faced a choice between a humiliating peace reducing them to a rump state around Yerevan, or complete annihilation. A few days later, the Soviets decided to take advantage of the situation and invaded the country. Ultimately hoping that Soviet backing might improve their position against the Turks, the Armenian government resigned in favor of local Bolsheviks on December 2; Soviet troops entered the city two days later; they would not leave until 1991.

British troops and Irish civilians outside a nearby hospital, during an inquiry into the shootings, a few days afterwards.

November 21 1920, Dublin–Since the establishment of Dáil Éireann in early 1919, Britain had slowly been losing control over much of Ireland, with taxes unable to be collected and courts non-operational in large parts of the country. Britain was understandably reluctant to commit large numbers of troops to Ireland–there was little appetite for a war in Ireland after the one in Europe, and a military crackdown would likely only make things worse. Nonetheless, the Royal Ireland Constabulary had been greatly expanded with “Black and Tans”–mostly discharged soldiers from the war, effectively forming a paramilitary force. A relatively low-scale conflict continued for nearly two years, with no more than a few thousand IRA members occasionally launching attacks on the RIC and British military intelligence.

This escalated dramatically on Sunday, November 21. Earlier in the month, British military intelligence in Dublin had captured a list of names and addresses of 200 IRA members in a raid. Michael Collins ordered the assassination of 50 men believed to be associated with British military intelligence; at Cathal Brugha’s insistence, this was reduced to 35, and then 20. In several independent operations early on November 21, 15 people were killed–some the intended targets, some RIC officers responding to the attacks, and at least one civilian.

Collins showed little compunction for the killings:

My one intention was the destruction of the undesirables who continued to make miserable the lives of ordinary decent citizens. I have proof enough to assure myself of the atrocities which this gang of spies and informers have committed. If I had a second motive it was no more than a feeling such as I would have for a dangerous reptile. By their destruction the very air is made sweeter. For myself, my conscience is clear. There is no crime in detecting in wartime the spy and the informer. They have destroyed without trial. I have paid them back in their own coin.

That afternoon, at a Gaelic football game, British troops and RIC arrived; it was claimed that they intended to search men exiting the game for weapons, but they began firing as soon as they reached the stadium, forced their way onto the pitch, and some shot into the fleeing crowd, killing 14 civilians.

Later that evening, three IRA prisoners captured in connection with that morning’s assassinations, were shot, supposedly while trying to escape.

The events of “Bloody Sunday” further galvanized Irish opinion against the British, and markedly escalated the conflict there. Within three weeks, martial law had been declared in large portions of southern Ireland.

November 15 1920, Geneva–The League of Nations General Assembly convened for the first time in its Geneva headquarters (later to be named the Palais Wilson after the President’s death in 1924), with representatives from 42 states. More notable, however, with the absences.

The United States, having never ratified the Treaty of Versailles, was not present, and did not even send an observer to the proceedings.

None of the defeated states–Germany, Austria, Hungary, Bulgaria, or Turkey–were League members, though Austria and Bulgaria would join the next month.

Russia was not present, as the Allies did not recognize the Soviet government and the Whites had largely been defeated. Apart from Poland, the states that had broken off from the Russian Empire were also absent: Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and the embattled Armenia and Georgia—though Finland would be admitted the following month.

Some other states were also not present, due to oversights or because they were not in any way part of the Allies: Mexico, Ecuador, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Luxembourg, Albania, and Ethiopia, along with European microstates such as Andorra. British dominions (including India but not Newfoundland) each had their own representation in the League.

White soldiers on board one of the ships leaving the Crimea.

November 14 1920, Sevastopol–The Soviets had launched what they hoped to be their final offensive against Wrangel in late October. Although they destroyed much of his army, enough of it was able to fall back to the narrow isthmus connecting Crimea to the mainland to mount a concerted defense. This, however, was overcome by direct and amphibious attacks between November 7 and 11, and it became quickly apparent that Crimea would soon be lost.

Wrangel had been preparing for such a possibility since his arrival in the spring, however, and he was much better equipped than Denikin had been when evacuating the Kuban in March. Wrangel left Sevastopol on the 14th, and simultaneous evacuations took place at at least four other Crimean ports. 146,000 White soldiers and refugees were taken across the Black Sea to Constantinople by the end of the evacuation efforts on the 16th, aided by a one-day pause by regrouping Soviets.

Those who did not or could not evacuate, however, met a grimmer end. Béla Kun was put in charge of Soviet administration in the area. The Cheka killed tens of thousands in the coming weeks. In Kerch, “trips to the Kuban” were organized: prisoners were taken out into the Sea of Azov and pushed overboard to drown.

Those who evacuated were interned and then lived in exile. Wrangel took with him the last of the Blask Sea Fleet, including the dreadnought General Alexeyev, were interned in French Tunisia until the French recognized the Soviet Union in 1924.

Sources include: Evan Mawdsley, The Russian Civil War; W. Bruce Lincoln, Red Victory.

“Battle of Bailleul. Men of the Middlesex Regiment holding a street barricade in Bailleul, 15 April 1918, just before the fall of the town.“ Taken by photographer John Warwick Brooke.

Source: Imperial War Museum.

Post link

“Battle of Albert. British troops attacking German trenches near Mametz. 1st July 1916.”

Source: Imperial War Museum.

Post link

A collection of animated stereoscopic photographs of French colonial soldiers from the French colonial territory of Indochina in Fleury-sur-Aire, France, during World War 1. Taken by French soldier Raoul Berthelé on June 25, 1916.

Source: Archives Municipales de Toulouse.

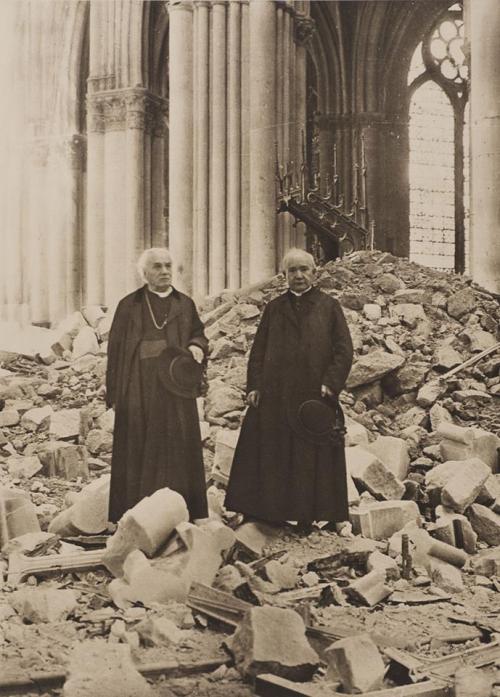

Reims after the First World War (1914-1918).

Notre-Dame de Reims après les bombardements de 1914-1918.

Post link

L'Ascension du poilu (French WWI infantryman), 1922, George Desvallieres

Source: http://www.georgedesvallieres.com/actualite2011_10_12_orsay_en.html

Post link

Douglas McMurtrie

A farmer, wounded in World War I, returns to work, 1918.

Historical Medical Library of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia

Post link

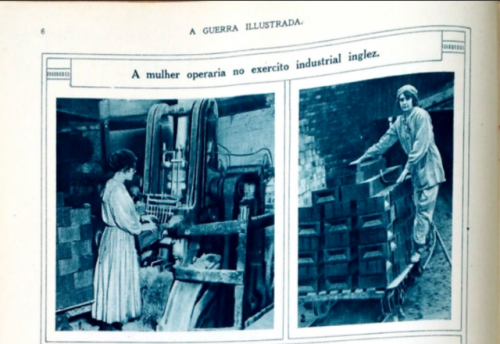

“THE OPERARY WOMEN IN THE BRITISH INDUSTRIAL ARMY”

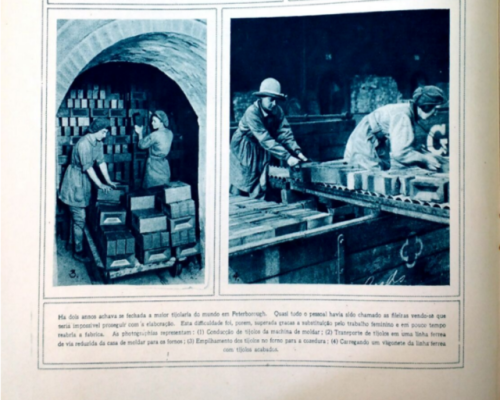

“Two years ago the world’s biggest brick factory closed its doors as all of its workforced enlisted to the british army. This difficulty, however, was overcome due to feminine workforce joining the fold and soon the factory was working again. In the pictures: (1) A woman filling a brick molding machine with mud; (2) transporting bricks from the molding machine to the furnaces; (3) setting the bricks into the furnace; (4) taking the finished bricks to the railways.”

Feminine work during the Great War played a big role in the conflict, as more and more men enslisted and the war escalated, women were the ones left to make the war industry going. This is argued as one of the first movements that influenced the creation of feminism and female emancipation movements such as that, as more and more women filled the gap left by men and started to demand equal rights.

Source: A Guerra Illustrada/”La Guerre Illustrée” (The War Illustrated). February, 1918.

Post link

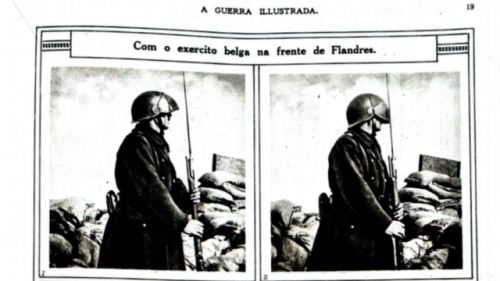

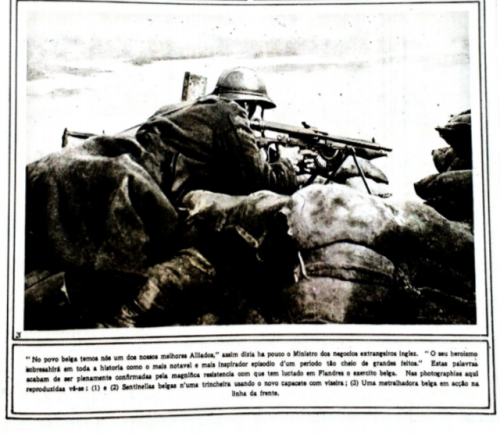

“THE BELGIAN ARMY AT THE FLANDERS FRONT”

“‘In the belgian people we have our best allies’ as would say the british minster of foreign affaris ‘Its heroism will be noted throughout all of history as most notable and inspiring episode of a period so full of great deeds’. These words just had been confirmed with the magnificent resistance that they had put up on Flanders.

In the photographs here you can see: (1) and (2) A belgian sentinel wathches over a trench using a new helmet; (3) A belgian machinegun in action on the frontline”

Source: “A Guerra Illustrada”/”Lá Guerre Illustré”, August, 1918.

Post link

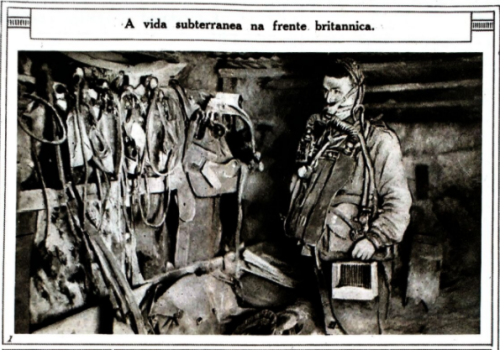

“THE SUBTERRANEAN LIFE IN THE BRITISH FRONT”

A british soldier prepares to go underground with diging and oxygen equipment. P.S.: Note the little cage in his hand, it was used to hold a bird inside of it and take it underground. If the bird died, it would mean that there was no more oxygen in the tunel.

Source: “A Guerra Illustrada”/”La guerre Illustrée”, August, 1918.

Post link

The Brain Scoop:

The Story of the Museum für Naturkunde

It’s here! Our first video in collaboration with the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin, Germany. 7 months ago this partnership was a glimmer of an idea that we were able to make a reality.

It’s nearly impossible to try and summarize more than 200 years of an institution’s history in less than 10 minutes, but we did it anyway. The truth is, any moment of time here could be magnified and examined for its nuance an detail; what stuck with me throughout this process was the idea that political decisions, whether local or global, ultimately shape our priorities for studying the world around us. And that despite those limitations, scientists and naturalists continue their pursuits within the confines of such restrictions.

What you get with this video is a neatly wrapped story – but what you don’t see are the hours I spent researching how scientists in East Berlin dealt with censorship and police spies, or the way Jewish scientists were treated during WW2, or how the country tried to recover from economic hardship after the first World War. I wish we had three more hours to dig into all of that, unfortunately we don’t– but, regardless, I’m proud of this video and for what it represents: we have hope for our future.

TheGewehr 98(abbreviatedG98,Gew 98orM98) is a German bolt action Mauser rifle firing cartridges from a 5 round internal clip-loaded magazine that was the German service rifle from 1898 to 1935, when it was replaced by the Karabiner 98k. It was hence the main rifle of the German infantry during World War I. The Gewehr 98 replaced the earlier Gewehr 1888 rifle as the German service rifle. The Gewehr 98, and especially its action, also directly influenced the design of many other military rifles of the era such as the M1903 Springfield, the M1917 Enfield and the Arisaka.

Post link