#easterlings

I dislike the use of ‘political’ in such a context; it seems to me false. It seems clear to me that Frodo’s duty was 'humane’ not political. He naturally thought first of the Shire, since his roots were there, but the quest had as its object not the preserving of this or that polity, such as the half republic half aristocracy of the Shire, but the liberation from an evil tyranny of all the 'humane’*–including those, such as 'easterlings’ and Haradrim, that were still servants of the tyranny.

Denethorwas tainted with mere politics: hence his failure, and his mistrust of Faramir. It had become for him a prime motive to preserve the polity of Gondor, as it was, against another potentate, who had made himself stronger and was to be feared and opposed for that reason rather than because he was ruthless and wicked. Denethor despised lesser men, and one may be sure did not distinguish between orcs and the allies of Mordor. If he had survived as victor, even without use of the Ring, he would have taken a long stride towards becoming himself a tyrant, and the terms and treatment he accorded to the deluded peoples of east and south would have been cruel and vengeful. He had become a 'political’ leader: sc. Gondor against the rest.

But that was not the policy or duty set out by the Council of Elrond. Only after hearing the debate and realizing the nature of the quest did Frodo accept the burden of his mission. Indeed the Elves destroyed their own polity in pursuit of a 'humane’ duty. This did not happen merely as an unfortunate damage of War; it was known by them to be an inevitable result of victory, which could in no way be advantageous to Elves. Elrond cannot be said to have a political duty or purpose.

* humane: this (being in a fairy-story) includes of course Elves, and indeed all 'speaking creatures’.

–J.R.R Tolkien, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, #183

Free Map: Sutrlûrza Khand

I made this for my MERP Campaign, but you can adapt it to yours as long as you need a Middle-Eastern/Arabic styled city. Tools used: Age of Empires II Definitive Edition’s map editor + Adobe Photoshop CS6 for merging and final details.

You can download the full image (98 MB - 16439x8379 pixels) clicking here.

Post link

“Here and there [was] the gleam of spears and helmets; and over the levels beside the roads horsemen could be seen riding in many companies… These were Men of other race, out of the wide Eastlands.”

J.R.R. Tolkien “The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers”

Post link

Famous Easterlings: Nyrguyana, the warrior-maiden

Excerpt from Züün Tzus - The Story of Rhûn.

When in the Second Age the clans Szreldor and Vulszev, who had been part of the Uldorians of Beleriand, returned to the east and settled in the vicinity of the Sea of Rhûn, the native Ulgath tribes of the area were subjugated by these newcomers, over all the northern Murgath tribes, who lived on the land we now know as Dorwinion. Thus was born the empire of the Shrel, name with which his kingdom was also known with Shrel-Kain as its capital city.

For a long time, the Murgath tribes had a low social status in the social ranks of the empire, until the time when the Shrel were called to arms by the armies of Sauron for the conflict we know as the War of the Last Alliance. Here an important division in the Murgath society occurred as there were many who responded to align themselves in the ranks of Warlord Shrel to win their favor. This folk would be known later as the Sagath (or Southern Murgath), who settled southwest of the Sea of Rhûn after the defeat in the plains of Dagorlad.

However, there were others who resisted the oppression of the Shrel and the most famous of these opposition guerrillas was the one raised by the warrior maiden known as Nyrguyana.

Nyrguyana was a peasant native to the plains north of Celduin, which were under the Shrel domain. She had two children with a carpenter who would later die of a lung infection. His eldest son, Nuböz, was enlisted for war by the landowner of where they lived and was slain in a skirmish with the armies of the northern kingdoms. It is said that Nyrguyana refused to lose her second son, whose name is not remembered in the books, when the Warlord of Shrel called the youths to enlist in the service of the armies of Mordor, and took action in this regard by secretly summoning women who were in the same situation. When the victims formed a large number of members, they went out openly to declare themselves against the policies of the leaders of the empire.

Of course the response of the leaders did not wait. First, they tried to use force forgetting that many of these women were wives of soldiers of their own empire who refused to repress, even under death penalty.

For fear that on the eve of war an internal conflict would break out, the Shrel Emperor tried to dialogue and reach an agreement with the leader of the revolution. It is said that the emperor did not imprison or kill Nyrguyana at that time for fear of creating a martyr of her figure, then offered the peasant her own weight in gold in exchange for disarming the conflict and surrendering their children to the ranks of his army.

It is said that Nyrguyana accepted the deal, but instead of fulfilling her part, she used the gold to arm her follower warrior mothers and any other volunteer who wanted to be part of the revolution. They painted their hands golden, or so the stories say, to demonstrate metaphorically that gold cannot buy blood and during a cold night, Nyrguyana, knowing that retaliation would not wait when the truth of the deal was known, guided the mothers and their young children outside the city heading north.

Evidently they were persecuted, but they prevailed in union escaping the tyranny of the Shrel. Some ancient writings of the Sagath name her as a witch who had bewitched the wolves of the north to fight at her side. Like all legends, there may be some truth in all this.

From the warrior mothers, a nomadic and matriarchal society emerged, who wandered through the steppes of the south and east of the Iron Hills. In the language of the Ulgath they were known as the Logath, which means “the refusers”, and their land is known today as Logathavuld, with its numerous divisions according to the clans that were emerging with the passage of time. We will return to this topic later. The truth is that to this day, the figure of Nyrguyana is almost as important in the history of the Logath as that of the goddess Uldona herself and is one of the most common names with which the parents baptize their daughters in the lands of Rhûn.

Years later, the Logath would be part of the coalition known as the Wainriders. But that’s another story.

Post link

Middle-earth March - Day 23

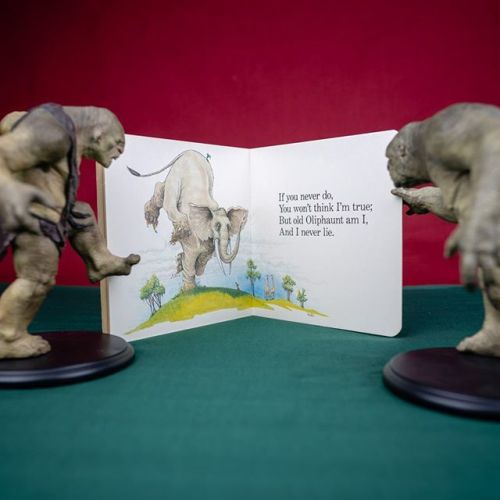

“What about the Oliphaunts?” is the question our friends over at @tolkientribeask for today’s Middle-earth March. We had a close look into our bookshelves and found this little treasure! It’s Tolkien’s poem “Oliphaunt”, lovely illustrated and published as a single cardboard book for little children. It’s also pretty rare and hard to get!

Post link

The first men awoke with the sun. Tolkien tells us almost nothing about the early days, but we know that the race of Men began with the first sunrise. And they didn’t have contact with the elves, or any of the valar, for a very long time. They lived in the East, near their place of Awakening, for over three centuries. Then, something terrible happened. We don’t know what it was, but according to Tolkien, it was the work of Morgoth. At least three separate tribes of men fled west, bringing them into Tolkien’s stories. An unknown number more remained behind. The pre-elven period of human history is almost entirely blank. Tolkien made a few weak suggestions, but never reached a sure conclusion about what happened.

Here’smysuggestion:

The first men were sun-worshippers. They awoke and saw the sun, and they worshipped her as their creator. The Elves venerated the stars in a similar way, but the first men never had the Valar to correct them, and so they viewed the Sun as the source of life.

(There is a very old story. It goes like this: the sun rose, and men awoke. They knew the world and they were filled with the joy of it. For a single day, they did not know death, and they did not know fear. Then came the sunset. And the darkness came into their hearts. They turned from their creator, and hid their faces in the dirt, and doubted that the sun would rise again. And so, because we did not have faith, all men must die. But, the old stories say; if we hold onto faith in the face of our mortality, and if we scorn the darkness, then our doubt may be forgiven. And when the world ends and the stars fall from heaven, there will come a bright day that lasts forever. And all the faithful men that have died in this world will return, and they will live in peace forever.)

Men were different from elves in another way too: they experienced death, and their new religion needed a way to explain their mortality and suffering. They attributed these things to the moon, seeing it as the sun’s direct opposite.

As opposites, the sun and moon represented life and death, good and evil, and all the other opposing forces of nature that were needed to form a complete world.

As time passed, men began to see the sun and moon as not just opposites, but as two parts of the single, divine being who had created them. The obvious extension of this belief was that other things in the natural world were also part of the creator, and also worthy of veneration. A system of animist worship gradually developed, and the sun and moon became the two most powerful and important symbols in a world filled with smaller spirits– mountains, trees, animals, and ancestors, who could be friendly or harmful. (There are probably Ents in here somewhere).

The first men had no written language before their contact with the elves, but they did have pictographic symbols, which were magically powerful and were often used in cave and rock painting. The sun and moon came to be represented as eyes– the two eyes of the Creator, looking down on her creations, and representing the different aspects (benevolent or uncaring) that she could present.

So, the single most important religious symbol to the first men was the Eye of Sun, looking down upon the earth with love, and representing the hope that the creator promised with every new sunrise.

You see where I’m going with this? An all-powerful, all-seeing, burning Eye?

Yeah. The men who went west may have forgotten their original faith in favor of what the Elves taught them, but everywhere else that men settled, in Rhûn and Harad, they took their sun-worship with them. It was the most widespread religion in middle earth for centuries, right up through the end of the third age. Sauron didn’t invent the symbol of the Great Eye, he parasitized it. It’s much easier to insert yourself into existing power structures than it is to make new ones, after all. And it made organizing resistance in the east that much harder– who wants to take up arms against the symbol of their own faith?

Tolkien was happy to gloss over everything in the south and east, but both Rhûn and Harad are huge continents, each one larger than ‘middle earth’ and there must be thousands of stories to tell. I want to know about how Morgoth broke the first cities of men, scattering them with fire and sword, and making nightmares out of captive flesh– new breeds of orc that would haunt humanity for ages to come. I want to know about the men who stayed behind in spite of all that. I want to know the story of how they rebuilt, the temple they raised on the site of their Awakening, the place western men say was lost to time. I want to know about the other languages they spoke, the ones that they created without elven influence. I want to know how the first human language, Taliska, came to be influenced by dwarvish, and what men did that made the dwarven tongue such a closely-guarded secret by the time the second age arrived.

I want to know about the empires– the middle-earth equivalents of China and Egypt and Zimbabwe, and the Balchoth with their chariots, and if there was ever a middle-earth version of the Mongols. I want to know about the fire-drakes of the north, and the tales about dragon-slayers that never get told in the west. I want to know about the pirates in the bay of Belfalas. And the veiled princesses in Khand, and their heroes questing after them. I want to know about the heroes that weren’t questing after princesses, because they were too busy questing after princes instead.

I want to know about Sauron. I want to know about the plagues he spread along the silk road, the lies he whispered in the right royal ears, the assassinations. I want to know about the other rings he gave to Men. I want to know about the blue wizards, the ones who vanished into the deserts, and the mysteries and cults that Tolkien says they cultivated there. I want to know about how Mordor fell, and what it’s name was before it was Mordor and it’s people were all slaves. I want to know about the first man to tame a Mûmak, and if she was really a man at all.

I want to know all the things the Numenoreans missed and forgot while they were busy imitating elves.

Easterlings, represent.

men of middle-earth⧎easterlings and southrons⧎headcanon disclaimer

When the Race of Men first Awoke in Hildórien upon the rising of the Sun, they soon divided into several distinct groups. Many traveled westward, while others moved to the South, but some stayed in these eastern regions, calling their birthplace the Land of the Sun. Untouched by Valarin influence, these eastern peoples’ first contact with the Powers was when Túvon, an emissary of Melkor, swayed them to the service of his Master. At first Túvon seemed a generous lord, but when Melkor revealed himself in his full might, it became clear that the Dark Vala had cast his shadow upon the East, claiming it for his own, and his influence upon the Men of the Land of the Sun would linger through many Ages.

Yet Melkor’s corruption was incomplete, and Men were ever prone to follow their own desires and be masters of their own will. Some, troubled by the conflict the Dark King stirred up in their homelands, embarked upon journeys to the West, seeking their kin who had gone before and lands free of Túvon and Melkor’s control. Though they were not to find the latter, these tribes led by KulrenandPegmûl would make their way to Beleriand, and become entangled in the histories of that land.

After Melkor’s defeat, for awhile the Men of the East were free of his oppressive darkness, but after a scant few centuries his surviving servants returned to their lands. Túvon established himself as a sorcerer upon the mount of Kalormë, the hill-crest over which the Sun rises, and ruled over the Sûhalar people in Mountains of the Wind, while his rival Thû conquered the region of Palisor and declared himself a God-King and the successor of Melkor. He manipulated the Men of Palisor, turning the horse-riding Khundolar tribe against their close kin the Chayasír, and built himself a castle in Khundoland from which he would rule.

As Thû’s influence spread, he commanded many towns and walls of stone to be built, and supplied his Mannish subjects with weapons of iron, amassing an army and turning their hearts against the men of the North and West. He first turned his might against Túvon’s stronghold in the Walls of the Sun, hewing down mountains and laying siege upon his former fellow-servant of Melkor. After a long and bitter war, Túvon at last surrendered, and Thû made him his thane. With his enemy turned to his service, Thû took his leave of the Land of the Sun for some time, departing into the Westlands with orders for his armies to prepare for another war.

When Thû returned some centuries later, he carried with him many Rings of Power, which he granted to the chiefest of his mortal servants: Khamûl, the regent of Khundolar, and Kullund, the pirate-queen of the Inland Sea. With these Rings they became fierce and powerful magicians, instilling terror upon their subjects and bending them ever to Thû’s will. These first of the Nazgûl led their Master’s armies against Eregion alongside orc-armies that poured forth from Mordor, and though eventually they were driven out of the Westlands, Thû kindled within the his eastern servants a hunger for the fertile lands west of the Sea.

When besieged by the elves and Men of the West, Thû called upon his eastern armies to support him against the Last Alliance of his foes. Yet despite the valour of the Men of the East, Thû fell in battle and was lost, his Nazgûl lords fleeing. His defeated servants returned to the Land of the Sun, released from Thû’s tyranny, and slowly began to rebuild their lives. Túvon retreated back into his stronghold upon Kalormë, letting the tribes of Men do as they pleased, which was often engaging in battle against one another, or to harrytheDúnedain of Gondor.

But Thû was not utterly defeated. His spirit, though much diminished, slowly pieced itself back together, and soon whispers were heard in the streets of Khundoland that the King of the Dark Castle stirred again. Thû’s influence was much subtler this time, and he whispered into the ears of Men rumors of Gondor’s wealth and the wildness of the Northmen, unjustly lording over lands they did not deserve. Thus the Men of the East were kindled to war, harassing Rhovanion and Eryn Galen all the way down to the Vales of Anduin, until they were driven out by the NorthmenandRómendacil II of Gondor, forced back to the Inland Sea of Tavukhor.

Yet it was not long before Thû’s mightiest servants returned to him: KhamûlandKullund, now only wraiths, marshalled their ancestral kindred into a confederation of Wainriders, leading them in a second conquest of Rhovanion and enslaving the Northmen. Their enemies had been devastated by a Great Plague, and proved easy to defeat, and even when King Calimehtar of Gondor gathered enough strength to strike back against them he was unable to reclaim the fullness of his former territory.

Now Thû moved to ally the wagon-riding Easterlings with his vassals to the south. Under his guidance, the Wainriders conspired with the Variags of Khand and the Hasharin of Abrakhân to lead a two-pronged attack against Gondor, while Khamûl and Kullund’s superior the Witch-King of Angmar harassed Arnor in the north. Though ultimately the Wainriders were defeated, slaughtered by Eärnil II in the Battle of the Camp, their campaign brought an end to the royal line of Gondor, and would weaken their Master’s enemies irreparably. Thû moved the Witch-King to Minas Morgul, while Khamûl was relocated from Khundoland to Dol Guldur, where Thû had dwelt in the guise of a Necromancer in order to spread his Shadow throughout the forest now known as Mirkwood.

With Arnor destroyed and Gondor dealt a heavy blow, Thû bided his time before making his next move. For some years, he allowed the Men of the East to recover, trading and farming and rebuilding their populations, but eventually he stirred them up once more into a second confederacy of Wainriders. When these folk, composed primarily of the Khundolar tribe with some soldiers of Jangovar descent, rode south to battle, their Gondorian foes named them the Balchoth, the “horrible horde,” and were shocked by the presence of many women among their troops.

Allied with orcs, the Balchoth overran the fair plains of Calenardhnon and were near to conquering the rest of Gondor, who were distracted by attacks by the Corsairs of Umbar in the South and could not mount a full defense. But just when victory seemed nigh, Éorl of the Éothéod rode to the rescue of Steward Círion, winning the Battle of the Fields of Celebrant and driving the Balchoth away. Yet some Easterlings lingered in the land, assaulting the newly formed Kingdom of Rohan and slaying Éorl in the Wold, their bloody conflicts providing a distraction that allowed Thû to reclaim the land of Mordor unnoticed.

In the War of the Ring, Thû sent his Nazgûl to muster an army of every tribe of Easterling to attack his enemies in this his final campaign. Khamûl emerged from Dol Guldur and drew all his folk of the Khundolar onto their horses and wagons; Kullund arose from the depths of Tavukhor and rallied her people, the seafaring Jangovar, to battle against the kingdoms of Dale and Erebor; Túvon was dragged out of his stronghold by the threat of Thû’s growing power, and led the stout, dwarf-like Sûhalar tribe who dwelt in his mountains to battle with their axes and cannons. Only the Chayasír refused Thû’s call to war, for which they would pay dearly in time.

At the Battle of the Pelennor Fields, the SûhalarandKhundolar fought alongside the orcs and trolls, the Variags of Khand, and the Haradrim warriors of Yettafaz, Rûvashû, Abrakhân, and Sud Sicanna. They laid siege to Minas Tirith, and it took the combined might of all the Free-peoples of the West to drive them back to Mordor, where Thû gathered his armies and prepared for a final assault to pour forth from the Black Gate. Yet the Men of the West brought the fight to him, marching to Morannon with a challenge, and once more the Easterling armies fought against their Western kin.

But this battle did not last long: near as soon as it began, it ended, for Thû’s tower fell and the land of Mordor crumbled beneath their feet as his power was ended in Middle-earth at long last, his Ring melted down in the fires of its making. The Men of the East and South fled, and in time were subdued by King Elessar of the Reunited KingdomandKing Éomer of Rohan, forced to pay tribute to the West until they could prove they would no longer harm their kingdoms.

With Thû utterly defeated, never to rise again, the Men of the Land of the Sun were at last free of the Shadow that had hung over them nearly since their first Awakening. The Khundolar,Jangovar, and Sûhalar returned to their homelands much-diminished, reorganizing their settlements and governments and eventually finding a balance between the Three Tribes that allowed them to live in peace.

But for the Chayasír, who alone had defied Thû’s might, their trials were just beginning. These folk, craftsmen and tradesmen who had no love for Thû and took no part in his War, were driven out from their homelands when their vengeful Master perished. On the very same day the One Ring was destroyed, Thû’s darkest designs were at last unravelled: their crops withered before their eyes, the corpses of their dead rose from their graves, and the earth shook beneath their feat. With his last breath, Thû had cursed his faithless followers, and the remnants of his Shadow seeped out of their lands as a living curse.

The Chayasír fled the destruction and disease of their homeland, turning first to Túvon and the Sûhalar in the Mountains of the Wind for aid, but the Sûhalar remembered their betrayal and refused them succor. Túvon may perhaps have wished for more mortal servants, but he was much diminished from his part in the War, and had not the strength to overrule the chieftains of the Sûhalar, who had long ago bargained with him for an equal role in their governance.

Thus the Chayasír embarked upon the long march into the West, the winds they once had loved turned sickly and sour at their backs. When at last they reached civilization, they were met with hostility from the dwarves of the Iron Hills and the Men of Dale, who had only just won a bloody war against the Jangovar of Tavukhor. The Chayasír did not hold themselves in kinship with the Jangovar, and even their ancestral ties to the Khundolar had long since been severed, but the northerners did not distinguish between the two Easterling clans and were openly hostile to the refugees.

As the Fourth Age began and the Three Tribes of the Sun worked to rebuild their civilizations in a world without Thû’s tyranny, the Chayasír strove to integrate themselves into the society of the North. It would take the intervention of King Elessar to allow them to settle in the wilderlands once desolated by the dragon Smaug, and their existence would be hard and bitter for generations, but eventually the Sun their mother would smile upon the Chayasír again, and sweet winds would blow once more over their fields, rewarding them at last for their refusal to serve the evil will of Thû.

Post link

@aspecardaweek day four | worldbuilding |a-spectrum symbols in arda

DAISIES❁ THE SHIRE

[3 images on a muted green background. 1: A pale hand holding two plucked daisies, with mountains in the background. 2: A light-skinned young woman with dark hair wearing a daisy flower crown. 3: Two pale arms holding a brown wicker basket mostly-submerged in still water, collecting floating daisies from the surface.]

Hobbits typically marry shortly after they come of age and produce large families, commonly with five or more children. Hobbits who do not follow this pattern are seen as “troublesome” and “queer.” While often the subject of gossip, these hobbits look out for one another, and have taken the daisy flower as a symbol of their queerness. They share this blossom with their fellows who are queer in other ways, such as those who desire a spouse of the same gender. The traditional white daisy crown symbolizes “lonesome” hobbits, while daisies dyed other colors have various meanings. This language of flowers is known mostly among queer hobbit socieities, and is meaningless to those outside their sphere. Wearing a daisy once or twice does not indicate one’s queerness; rather, the daisy pattern is only a tell when worn repeatedly and incorporated into one’s personal style.

BIJEBTORV’AFÂH▣ THE DWARVES

[2 images, the first on a burgundy background and the second on a teal background. 1: Close-up of two black beads sitting on a rock. 2: Close-up of a brown mustache with two gold beads at the ends; the person with the mustache has pale skin and part of their beard is visible.]

Beads are often placed in dwarven beards, but when woven into mustaches, they take on a specific meaning: an indication that one is bijebtorva, or has chosen their craft over marriage. Less than a third of the dwarven population marries, and it is custom for a dwarf to only marry once for truest love. Though only those of noble houses are pressured to wed and reproduce, most dwarves are open to the possibility should it come their way. Bijebtorvadwarves are the exception, choosing not to wed at all, and by the wearing of beads in their mustaches they symbolize that they are not available for courting. These beads, known as bijebtorv’afâhor “beads of the craft-chosen” are of great spiritual import and are always crafted by the wearer themself.

URUSINDO ♦ THE FALMARI

[6 images on a muted purple background. 1: Three copper rings, each with a different colored gem; one is yellow, one is light green, and the last is blue. 2: A copper ring with a bright green gem. 3: A copper ring with a pale pink gem. 4: A copper ring with a yellow gem. 5: A copper ring with a purple gem. 6: Several copper rings bearing gems of pink and green.]

Among the Falmari, the custom of urusindo, meaning “copper-heart,” is an alternative way of approaching relationships, bonding, and love. Rather than engaging in a traditionally romantic, monogamous marriage, those who practice urusindofind companionship without physical coupling and sometimes without singular commitment to their partner. To mark such relationships, the edar involved wear rings of copper in place of silver betrothal or golden marriage rings. These copper rings each bear a single jewel, its color signifying the nature of their affection for one another. Warm colors represent unbonded pairs; pink for those who seek other companionship outside of their urusindopartner, and yellow for those who do not. Cool colors represent bonded pairs; purple for those who are open to other bonds, and green for those who are exclusively committed to their urusindopartner.

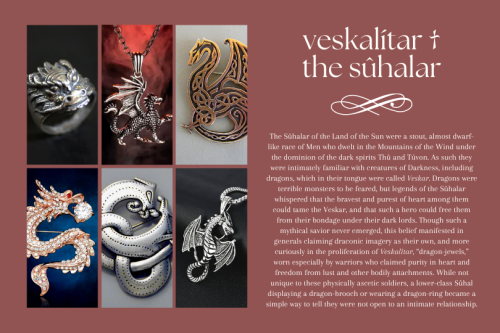

VESKALÍTAR † THE SÛHALAR

[6 images on a muted red background. 1: A silver ring emblazoned with the face of a dragon. 2: a silver pendant of a rearing dragon. 3: A stylized gold-and-black dragon brooch. 4: A rose gold dragon brooch bedazzled with small white gems and holding a larger white gem in its mouth. 5: a simplified silver dragon brooch. 6: A silver pendant of a legless dragon.]

TheSûhalar of the Land of the Sun were a stout, almost dwarf-like race of Men who dwelt in the Mountains of the Wind under the dominion of the dark spirits Thû and Túvon. As such they were intimately familiar with creatures of Darkness, including dragons, which in their tongue were called Veskar. Dragons were terrible monsters to be feared, but legends of the Sûhalar whispered that the bravest and purest of heart among them could tame the Veskar, and that such a hero could free them from their bondage under their dark lords. Though such a mythical savior never emerged, this belief manifested in generals claiming draconic imagery as their own, and more curiously in the proliferation of Veskalítar, “dragon-jewels,” worn especially by warriors who claimed purity in heart and freedom from lust and other bodily attachments. While not unique to these physically ascetic soldiers, a lower-class Sûhal displaying a dragon-brooch or wearing a dragon-ring became a simple way to tell they were not open to an intimate relationship.

AIRËVASAR✬ THE NIENNILDI

[2 images, the first on a muted orange background and the second on a blue background. 1: A woman with brown skin and bleached hair wearing a blue robe, a many-rayed crown, and a gauzy blue veil. 2: A woman with brown skin and dark hair wearing a gold robe patterned with suns, gold jewelry, and a gauzy white veil.]

Following the tradition of the Noldor, veils were popularized in early Númenor by Lady Halyamórë, wife of Vardamir Nólimon. Halyamórë was a devotee of Nienna and wore the veil in her honor, and though for many Númenórean noblewomen veil-wearing was a fashion for formal events, veils retained their religious symbolism, earning the name airëvasar, “holy veils.” Airëvasarvaried in style and meaning, but a gauzy facial veil became the specific symbol of the Niennildi, women who devoted themselves to Nienna’s service and swore never to marry, as their Valië was herself unwed. For many this was a political choice, but other Niennildi took the veil for personal reasons, especially to avoid unwanted betrothals and romantic pursuits altogether.

꧁NINKWI-HELTHWIN OF THE LAIKWENDI꧂

[3 images on a muted purple background. 1: Dark-skinned feet with white henna patterns. 2: A dark-skinned back with white henna patterns. 3: Dark-skinned hands with white henna patterns.]

Among the Laikwendi of the Silvan realms, helthwin(lit. “swirling skin”) is the practice of painting one’s skin with semi-permanent dyes extracted from native plants. Helthwinink is applied as a leisure activity or to show one’s artistic skills, and is commonly worn at festivals and revels where much skin is bared; it may also be worn into battle or diplomacy as a cultural symbol of the Laikwendi. Most helthwinink is a dark red or brown in color, but especially at revels where elves often take lovers for the night, specially treated white ink called ninkwi-helthwin is worn to indicate an individual has no interest in partnering. Developed from this custom, many Laikwendi who have no desire to wed or lay with another will take to applying ninkwi-helthwin ink to their skin in their daily lives as a marker of their general preferences.

Post link

![“ Here and there [was] the gleam of spears and helmets; and over the levels beside the roads horseme “ Here and there [was] the gleam of spears and helmets; and over the levels beside the roads horseme](https://64.media.tumblr.com/de680ab466a76233a8eea6bbbfdd13e2/tumblr_pqkp9xVE9q1sqop9ro5_400.jpg)

![“ Here and there [was] the gleam of spears and helmets; and over the levels beside the roads horseme “ Here and there [was] the gleam of spears and helmets; and over the levels beside the roads horseme](https://64.media.tumblr.com/20ab9985949f14ec4a6e484c8b7eb1a5/tumblr_pqkp9xVE9q1sqop9ro3_400.jpg)

![“ Here and there [was] the gleam of spears and helmets; and over the levels beside the roads horseme “ Here and there [was] the gleam of spears and helmets; and over the levels beside the roads horseme](https://64.media.tumblr.com/3902536b1a2b72716f4fc2cefa1d35c0/tumblr_pqkp9xVE9q1sqop9ro6_400.jpg)

![“ Here and there [was] the gleam of spears and helmets; and over the levels beside the roads horseme “ Here and there [was] the gleam of spears and helmets; and over the levels beside the roads horseme](https://64.media.tumblr.com/c1923486f505016467d8c0536243997f/tumblr_pqkp9xVE9q1sqop9ro4_400.jpg)

![“ Here and there [was] the gleam of spears and helmets; and over the levels beside the roads horseme “ Here and there [was] the gleam of spears and helmets; and over the levels beside the roads horseme](https://64.media.tumblr.com/269626aefef8e4bdb122c57c8fa1a5cf/tumblr_pqkp9xVE9q1sqop9ro7_500.jpg)