#ancient near east

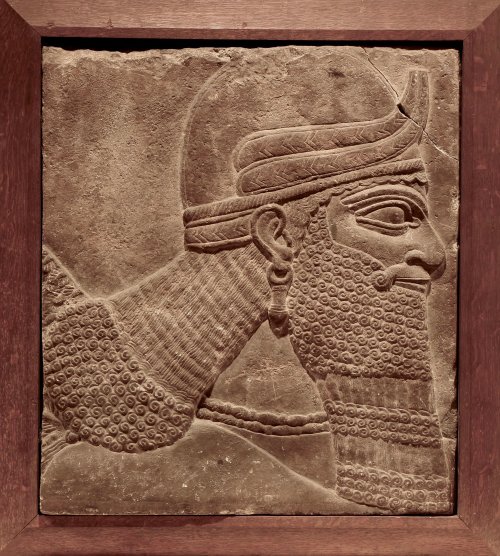

Glazed Wall Panel from Fort Shalmaneser

Fort Shalmaneser, Nimrud (Iraq). Reign of Shalmaneser III, 858-824 BCE.

Collected by Raymond Pitcairn during the 1920s, the Assyrian reliefs in Glencairn’s Ancient Near East gallery are “an exceptionally well-chosen group, representing diverse aspects of the religion, ideology, and artistry of the Assyrian Empire and typifying the development of the genre over time” (Eva Miller, University of Oxford). In this 2016 essay for Glencairn Museum News, Eva Miller examines the meaning of the images in these reliefs and how they have been received in both ancient and modern times: https://bit.ly/2D19XKF

Post link

Today, I’ll be making a quick and easy sesame snack from the Cretan Iron Age! A treat so sweet that it’s still popular today (with a few adaptations of course) - the koptoplakous as it’s known in antiquity - or the Pasteli as it’s known today!

In any case, let’s now take a look at The World That Was! Follow along with my YouTube video above!

Ingredients

200g sesame seeds

200g honey

sea salt (to taste)

Method

1 - Toast the Sesame Seeds

To begin with, we need to lightly brown and toast 200g of sesame seeds. Do this by tossing them into a hot pan, and letting them cook over a high heat for a couple of minutes. Don’t let these sit still, keep them moving around the pan so they toast evenly! Do this for about 5 minutes, or until your seeds are nutty and fragrant.

Take these off the heat, but keep them warm while you deal with the honey.

2 - Boil Honey

Next, place a pot onto a high heat. Into this, scoop about 200g of honey and let it heat up. Keep stirring it occasionally with a wooden spoon, so it doesn’t burn. Let this cook away over high heat until it foams up significantly. Much like boiling milk, this will happen very quickly, and might catch you off-guard. If it looks like it’s getting too high, take it off the heat and it’ll cool down pretty quickly.

3 - Mix Honey and Sesame

After about 10 minutes of foaming, turn the heat down to low before tossing in your toasted sesame seeds. Stir all of this together and let it cook for another 5 - 10 minutes. The honey should start to turn a deeper golden brown, but if it gets too dark, take it off the heat immediately.

When it’s been mixed together, pour it out onto a baking tray lined with paper. Spread it out into a fairly thin layer, but not too thin! Let it sit like this for about 20 minutes or so, before slicing it into segments with a knife.

You can serve this up whenever it’s cooled like this, or leave them overnight to re-solidify a little more! Either way, the finished dish is super sweet, and has a delicious nutty flavour, thanks to the toasted sesame seeds.

The modern name for this dish - pasteli - has its origins in medieval Italian cuisine, as this kind of sweet treat is common throughout Europe, the Near East, Asia, and the Indian subcontinent. Though obviously, each region has its own takes on this basic formula, such as the addition of local spices, nuts, or other ingredients!

Today, I’ll be going back to the Hellenistic Period, to the Hasmonean dynasty of Judea. The recipe in question is a simple honeyed-hens, recorded by Seleucid accounts of a feast held by one of the ruling elite. Though the original recipe refers to it plainly as chicken with honey, I’m going to be recreating it today based on our knowledge of contemporary dining habits!

In any case, let’s now take a look at the World That Was! Follow along with my YouTube video above!

Ingredients

4 chicken thighs

salt (to taste)

pepper (to taste)

ground cumin

ground coriander

2 tbsp wholegrain mustard

2 tbsp olive oil

2 tbsp honey

2-4 cloves garlic

Method

1 - Prepare the Chicken

To begin with we need to season our chicken. Do this by sprinkling some salt, some freshly ground black pepper, some ground coriander, and some ground cumin on top of your chicken, before rubbing it in with your hands. In antiquity, chicken would have been eaten, along with wildfowl like duck, and even doves or pigeon. Any of these birds would work well here, but chicken would be the easiest meat to deal with today.

Leave your chicken aside while you go make the sauce.

2 - Prepare the Sauce

Next, we need to make a sauce to go with this. In antiquity, mustard seeds and vinegar would have been the base of several sauces or condiments. You can easily do this here, but a better solution would be to use pre-made wholegrain mustard, like I’m doing.

In any case, toss about a tablespoon or two of mustard into a bowl, along with a good glug of olive oil. On top of this, add an equal amount of honey, along with a few crushed cloves of garlic. Mix all this together into a fairly thick sauce. If you want, you can thicken this over a medium heat for a few minutes until it’s just about bubbling. I didn’t do this, but it turned out well!

3 - Assemble the Dish

Toss your seasoned chicken into a lightly oiled baking dish. Pour over your sauce, and try and spread it around evenly. If you want to, you could place the chicken into a Ziploc bag with the sauce and leave it to marinate overnight in the fridge.

Either way, place your prepared chicken into an oven preheated to 200° C / 400° F, and let it all bake away for 40 minutes, flipping them over halfway through so they cook evenly.

Take the chicken out when they’re browned and cooked through, serve up warm on a bed of edible greens like rocket, and dig in!

The finished dish is super succulent and flavourful. The spices were very floral and nutty, improved by the time spent baking. The mustard and honey mix caramelised at the bottom of the baking dish, which was a delicious bit of sweet heat when serving up!

The meat itself was very tender, with the skin on top crisping up significantly during the cooking process. In antiquity, it’s unknown if birds were divided up into legs, wings, thighs etc, before or after cooking. Though it’s likely that they may have been prepared both as a whole roasted chicken that was then divided up at the table, as well as pre-cut into more easy to manage pieces like I did here. It’s really a matter of personal preference today anyway.

Today, I’ll be making a medieval drink from 13th century Egypt - and is still drunk today! A simple, refreshing drink called subiyah/ It was originally made to drink during Ramadan - a holy month of fasting in the Islamic calendar - but this is able to be enjoyed around the year! It’s simple to make, and has a very nice crispness to it!

In any case, let’s now take a look at The World That Was! Follow along with my YouTube video above!

Ingredients

3-4 slices of sourdough bread (crusts removed)

3-4 cups water

1 tsp cardamom pods

fresh mint

fresh parsley

Method

1 - Soak and Strain Bread

To begin with, de-crust three slices of sourdough bread and tear the bread into small chunks, before placing them in a bowl. The original recipe requires “bread” and gives no elaboration - so I went for sourdough because it has a more distinct taste than a regular slice of white bread.

In any case, pour in three cups of water into your bowl to soak the bread. Leave all this to get soggy for about thirty minutes. After thirty minutes, your bread chunks should be saturated with water, and practically falling apart. At this point, strain the bread water into a container that can be easily sealed. Make sure you remove as many solids from the mixture as you can.

2 - Combine Aromatics and Spices before fermenting

Next, toss some parsley leaves into your container with the water, along with some fresh mint, and a handful of cardamom pods that you’ve crushed slightly. Mix everything together, and seal up. I used a mason jar for this, because it’s convenient - but in antiquity, people would have used a damp cloth placed over the opening of the container.

Leave the container aside for a day or two at room temperature. This will let the whole thing steep, letting the flavours mingle.

When it’s done steeping, pour your subiyah through a strainer, removing the herbs, pods, and any remaining large chunks of bread. Serve up chilled, with a sprig of mint and take a sip!

The finished drink is quite mild tasting, but has a very soothing background sensation. It’s very light, and looks a lot like lemonade. A wonderful drink to have on a warm day!

Today, I’ll be making an Egyptian dish that dates to the pre-Dynastic period (the bronze age) - a simple herb and egg omelette that’s still eaten today: “eggah” (in modern Egyptian Arabic). The first records of this dish come from early Arab writers, discussing a much older dish!

In any case, let’s now take a look at The World That Was! Follow along with my YouTube video, above!

Ingredients

6 eggs

1 onion

fresh parsley or cilantro

ground cumin

ground coriander

salt

pepper

olive oil

Method

1 - Chop and cook onion

To begin with, chop a single onion in half, and peel off it’s outer skin. Then slice and dice the onion into small pieces, making sure they’re all the same size.

Then, pour some olive oil into a pot, and place it over a medium-high heat. When the oil is shimmering, toss your onion into it and let it sauté away while you mince your parsley. Or coriander, if it doesn’t taste like soap to you.

When your onion is soft and translucent and fragrant, toss in your parsley. Let everything sauté away over medium-high heat until the parsley wilts slightly. Leave it aside to cool a bit while you deal with your eggs.

2 - Mix Ingredients

Crack six eggs into a bowl while your onions are cooling. In antiquity, Egyptians would have had access to wildfowl and dove eggs - but chicken eggs work just as well. Next, toss in a tablespoon or two of ground cumin and ground coriander. On top of this, add a tablespoon of flour to help thicken things up. When the onion and parsley mix is cool, toss them into your egg mixture, and whisk them to combine.

3 - Prepare Baking Dish and Bake

Pour some olive oil into a baking tin, and spread it around. Next, pour in your egg mixture. It should settle evenly. Place this tin into the centre of an oven preheated to about 180C/356F and let it cook for about 25-30 minutes, depending on your oven.

It should be done when the top has puffed up and turned a lovely golden brown.

Take the dish out of the oven and let it cool for a few minutes. The top of this will collapse and deflate, but don’t worry, this is what’s meant to happen! Cut it into slices, and serve up warm!

The finished dish is very light and fluffy, with a slight sweetness thanks to the onions. Modern eggah has tomatoes and peppers included in the recipe - but neither of these were available to the region until the Columbian Exchange of the 15th century onwards.

However, early Arabic records about the dining habits of pre-Islamic Egyptian populations references a dish of baked eggs and herbs - which effectively suggests a pre-existing dish like this that was eventually adapted into the eggah we know today!

Cuneiform tablet counting beer for the workers. Circa 3100-3000 B.C, from Uruk in what is now southern Iraq. Now in the British Museum.

The beer on the tablet is represented by a jar with a pointed base. Food is symbolized by a head eating from a bowl (bottom left). The semicircular imprints (possibly made by the edge of a finger) stand for the measurements.

~Hasmonean

Post link

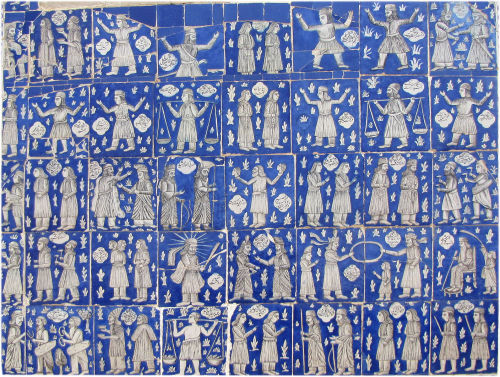

Almost halfway done with the Phoenician alphabet oracle. There are 22 letters/cards in total and I’ve worked 16 deities into it (the Phoenician, Canaanite and Mesopotamian gods are so heavily syncretized through both geography and time that it was a challenge to choose among all the figures and portrayals, but the full list is below the cut:

Post link

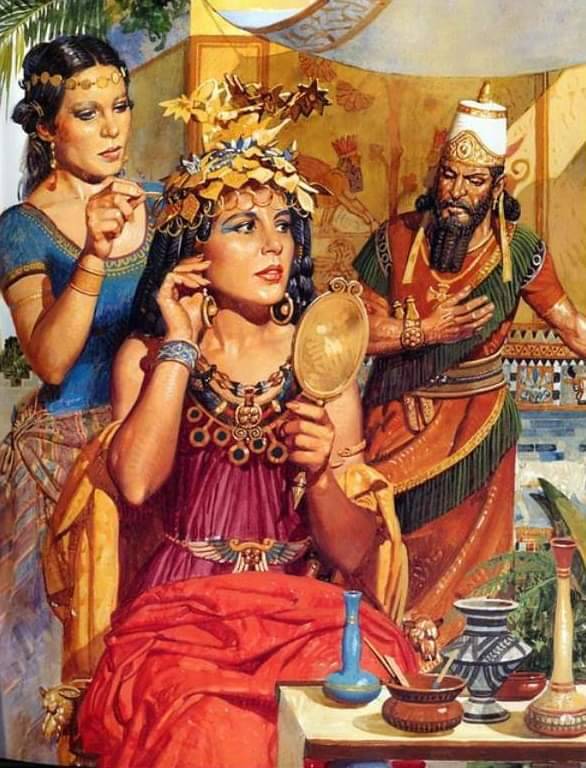

Queen of Assyria, Semiramus, by Roger Payne

Fravashi(fravaši,/frəˈvɑːʃi/) is the Avestan language term for the Zoroastrian concept of a personal spirit of an individual, whether dead, living, and yet-unborn.

Post link

~ Bull’s head ornament for a lyre.

Period: Early Dynastic III

Date: ca. 2600–2350 B.C.

Place of origin: Mesopotamia

Culture: Sumerian

Medium: Bronze, inlaid with shell and lapis lazuli.

Post link

Neo-Assyrian stamp seals depicting a dog (top) and the goddess Gula on her throne resting on a dog with an attendant. Circa 700-600 B.C. Now in the British Museum.

Gula was the Assyrian goddess of healing and the dog was her attribute. It was believed that if you neglected or harmed your dog then that would incur the goddess’ wrath.~Hasmonean

Post link

The Bull-Headed Lyre of Ur, the world’s oldest surviving stringed instrument, dating back to ancient Mesopotamia’s Early Dynastic III Period (2550–2450 BCE). University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, PA.

Photo by Babylon Chronicle

Post link

Enheduanna is the world’s earliest known author. A woman who wielded incredible power and authority, her legacy has stretched over time longer than she likely ever anticipated.

BASIC BIO: (c. 2300 BC) Enheduanna was the daughter of King Sargon of Akkad, and appointed by him to be the high priestess of the goddess Inanna and god Nanna in the Sumerian city of Ur. This politically-motivated move (he knew she’d be good for unity in the kingdom) exposed Enheduanna to great power, and she was essentially responsible for Sumer’s entire spiritual system. In her capacity as priestess, she composed a number of poems and hymns, not only in devotion to her gods, but also in reference to herself. She is, to date, the first example of an artist who signed her work.

HER IMPACT: Enheduanna continues to be celebrated around the world for not only her writings, but for the social and political significance of her role as high priestess. Her writings are available to read online, and offer an interesting insight into the education and literacy of women in Sumerian culture. Neil deGrasse Tyson’s Cosmos series dedicates some time to her, and she is the subject of many modern feminist debates. Perhaps my favorite thing about Enheduanna is that what we know about her is informed largely by what she wrote about herself - it’s not the most unbiased portrait, but I love that she herself was allowed to create it.

Post link

Phoenician depiction of a sphinx made of ivory. Depictions of them were not solely restricted to Egypt. From Fort Shalmaneser in northern Iraq, circa 900-700 B.C. Now in the British Museum.

~Hasmonean

Post link

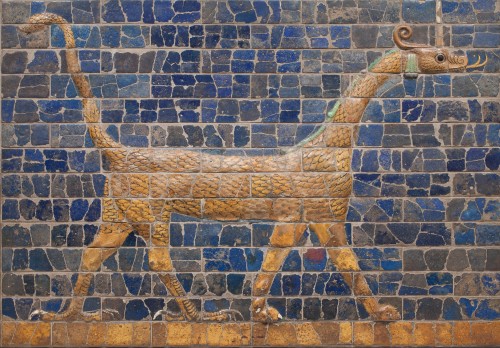

The Ishtar Gate (restored), Babylon, Iraq. 575 CE.

- Nebudchadnezzar II is the patron of restorying Babylon to glory. The book of Daniel speaks of him as an evil king.

- Has molded reliefs of animals, both real and imaginary: bulls, dragons, sacred lions.

- Depicted animals because they wanted to model themselves after their attributes. A powerful man wants to relate himself to a lion (power) or a bull (brute force, fertility).

Post link

Lamassu, Dur Sharrukin (Modern Khorsabad), Iraq, 720 - 705 BCE.

- made a limestone; carved detail is shallow, reveals how tough the material is to carve in. measures 13’ 10".

- winged, human headed bull

- the Assyrians were a militant civilization

- these two figures guarded the gates of the palace

- colossal sculpture - always has some kind of political significance. designed to be at the kings gate to ward off and cause fear in enemies.

- has five legs; wanted to show complete image of the monster. no matter what angle the sculpture is viewed, the form is complete. almost in-the-round.

- illustration of power and authority

Post link

Stele with Law Code of Hammurabi, Susa, Iran. 1780 BCE.

- record of the first written comprehensive law code for civilization

- eastern cultures considered the most advanced for this time period.

- two figures pictured: Hammurabi and Shamash, the sun god.

- Shamash is sitting down and is larger. Usually people of higher status are sitting down and everyone else comes to him. He is pictured with more elbatorate dress; clothing is worn only as a symbol of status.

- Hammurabi is standing. Raising his right arm, acknowledging the authory of Shamash.

- Shamash is offering a rod while orating to Hammurabi. Gesture of extending power to the mortal. The rod is a building material, symbolizes the building of social order (order is created through laws). The rod also indicates the ruler’s ability to lay down the law and punish.

- The laws recorded on the stele covers everything from commerce, property, and murder to marriage and fidelity.

- Examples include: wives and their lovers are killed when they commit adultery. Stealing, cheating, or lying about products was forbidden. Eye for an eye kind of punishment for crimes. If someone stole from the temple, they were put to death; you can tell where people’s priorities are depending on the severity of the laws against them.

Post link

Votive Disk of Enheduanna, Ur, Iraq. 2300 - 2275 BCE.

- made of alabaster; 10" in diameter.

- votive - an offering of thanks, almost always related to religion.

- Enheduanna is the daughter of the King of Sargon. She is a princess, priestess, and poet.

- Commemorates Ananna, a moon goddess (hence the round shape).

- The disk is honoring Enheduanna’s worship of the goddess.

- Princess is the second figure from the left, indicated by hierarchic proportion.

- There is a priest, nude, making an offering to the altar of Ananna. Two female attendants are behind Enheduanna.

- Praying with only right hand, sign of respect.

Post link

The Victory Stele of Naram-Sin, Susa, Iran. 2254 - 2218 BCE.

- made of pink sandstone; measures 6'7".

- commemorates a battle against Lullubi, in which Naram-Sin is the victor

- Naram-Sin is the largest figure; wearing a horned helmet, which is a connection with the gods and symbol of divinity. Associated with holiness.

- Hierarchic proportion - people are proportionate to their status; the most important figures are large, least significant are small.

- two distinct armies. the victors are larger.

- an organized army is a successful army. losing army in disarray, scattered and in different postures. regimented army is another indication of civilization/civilized society.

- three stars indicate it was destiny that Naram-Sin won and that he is favored by the gods; the military victory has religious significance.

Post link

Statuettes of Worshippers, Square Temple at Eshnunna, Iraq. 2700 BCE.

- made of gypsum inlayed with limestone.

- male figure 2’ 6" high.

- representation of religious mortals in a state of prayer. actually holding beakers used in Ancient Sumerian religious rites.

- some have inscriptions because they were donated/sponsored.

- very simple forms, geometric

- they are disproportionate. large eyes suggest alertness to the word of the Gods, openess of the soul. large feet a sign of humanity, being very grounded and suggesting solidness. they are in the act of worshipping, indicated by the body posture; standing indicates reverence and respect, and kneeling indicates humility. crossed hands indicate they are in the act of worship.

- stylized with purpose: there are very few accidents in art, because things are done for a reason. if there is something off, you need to ask yourself why.

Post link

White Temple and Ziggurat, Uruk (Modern Day Warka), Iraq. 3200 - 300 BCE

- demonstrated the essential role of the gods in Sumerian Culture

- religious monument often the centerpiece of the city

- temple complex is the city with in a city; had a staff of priests and scribes that worked official (religious) and commercial business

- considered the ‘white temple’ because it was white washed to represent purity

- built several centuries before the pyramids, so sumerians were building monumental structures before the egyptians

- not 'for everyone’; only housed priest and maybe some officials. represented everyone but designed only for a few.

- dedicated to Annu, the sky god

Post link

The Sumerians are the first sign of civilization; early peoples give up the dangerous and uncertain life of the hunter/gatherer for the more permanent life of the farmer/herder. Civilization was arranged in city states; they had a code of laws, currency, and value the good of the community over the family (for example, you could not kill a man for family honor because it would damage the community as a whole).

This is also the first instance of written documents; the Sumerian language was made up of pictographs - pictures that indicated words, the early precursor to the hieroglyph. The most famous document found is the Epic of Gilgamesh, which told the story of the King of Uruk.