#manic pixie dream girl

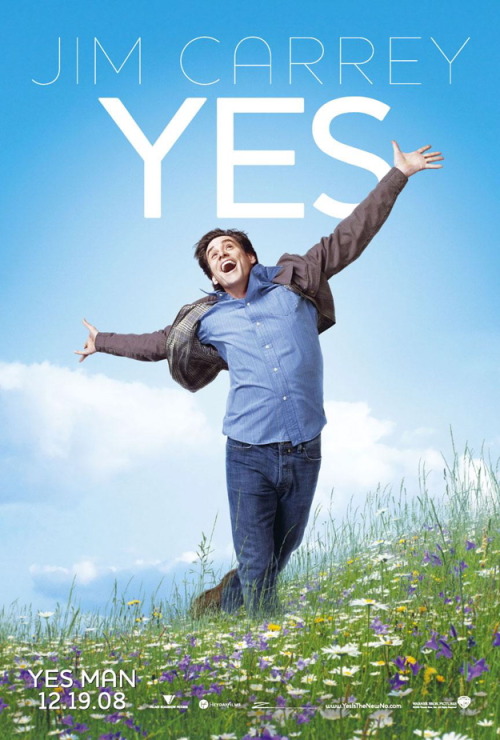

Yes Man: In which Jim Carrey discovers that he can say “Yes” to any strange suggestion without fear of reprisal because he’s a white man whose safety and power can never be undermined.

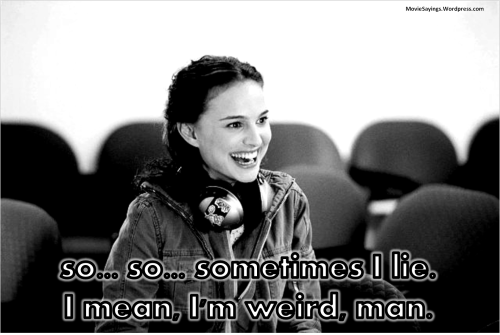

Is Zooey Deschanel a Manic Pixie Dream Girl? (Are you really asking this question?)

Post link

One of the MPDG’s key functions is that of representational transaction, or signifying the masculine in relation to another masculine identity or, more often, the masculine in relation to the public sphere of organized patriarchy. –Thesis Rough Draft, Chapter 1

(this is getting way less fun, and way more multisyllabic)

I just noticed how much of Zooey Deschanel’s wardrobe in 500 Days of Summer is very 50s housewife. Or, if you want to be trendy about it, “1950s chic.”

Subliminal messages about gender roles, anyone?

Post link

On that subject, how many films with an MPDG do pass the Bechdel Test (I think Garden State does; but I can’t think of any others)?

Post link

Ruby Sparks IS a manic pixie dream girl… and that’s okay. Zoe Kazan, the writer of Ruby Sparks, is emphatic that the movie is not a conscious response to the Manic Pixie Dream Girl, but she adds that “I’m very happy to have this movie read as a critique of that, if that’s how you want to read it.”

And that’s exactly how I want to read it, because Ruby highlights the dangers of treating women like characters who exist “solely in the fevered imaginations of sensitive writer-director[s].”

Post link

Despite the Internet’s best efforts to argue otherwise, the Manic Pixie Dream Girl does and must always have chronological limits. She is not a timeless trope. In coining the term, film critic Nathan Rabin used a vacuous definition; the manic pixie dream girl is an affable woman who “exists solely in the fevered imaginations of sensitive writer-directors to teach broodingly soulful young men to embrace life and its infinite mysteries and adventures.” While this definition does not seem time-bound, it is helpful to remember that Rabin wrote in 2007—not even a decade ago—and that his two prime examples of MPDG are Elizabethtown (2005) and Garden State (2004). And that “broodingly soulful young men” aren’t what they used to be—in the last decade, young men striving through existential quandaries are as self-conscious of feminism as young women. Feminism has permeated society and certainly, part of the question young men struggle through is how to be masculine without being patriarchal. If it is true that no one wants to be a feminist, no one wants to be a misogynist, either.

The film critics at the AV Club (including Rabin) may argue that “the strangely resilient archetype has its roots in the nutty dames of screwball comedy,” but the Manic Pixie is not the same as her predecessors. Efforts to conflate the MPDG with earlier Hollywood women (Audrey Hepburn in the 1961 Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Diane Keaton in the 1977 Annie Hall, or even as recent as Meg Ryan in the 1990 Joe Versus the Volcano) is misguided at best and diminutively damaging at worst. Rabin adds that the MPDG emerges from a world in which “no existential quandary is so great that it can’t be solved by the perfect combination of pop song and dream girl, a world of giddy pop epiphanies and gentle humanism unencumbered by protective irony or sneering cynicism.” This world, which he cites as the talent director Cameron Crowe brings to film, is socially and temporally located. The allure of this world is its response to cynical postmodernism, mass-produced music production techniques, and a desperate need for Western society to rethink the dream girl which for so long, Disney held captive in princess narratives. The Manic Pixie Dream Girl exists because the dream girl no longer does.

However, there is a second reason to delineate temporal boundaries for the MPDG. Limiting the trope temporally prevents overuse and prevents “lazy cultural commentary.” As Clem Bastow (and many other female critics) argues, naming the MPDG as a trope led to an obsession with naming her as an individual. Bastow worries that the Manic Pixie “has become a handy way to dismiss female characters out-of-hand.” As a result, she warns, “we might be doing damage to the career trajectories of the very real women who are writing, directing and starring in these films.”

These concerns are legitimate; however, the (fictional) trope of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl remains valuable because it illustrates the challenges of a generation struggling to create new gender identities in the wake of feminist conscientization.

The role of film is cultural storyteller. The fictional world of Hollywood provides paradigms for us to live into, to frame our own lives, to embody or to reject. As young girls grow into women, embodying or rejecting the Manic Pixie, they do so in a complicated matrix of what it means to be female. We must be able to name the trope, but we must name it accurately, as the product of a culture that has tamed feminism, subdued radical female search for selfhood, and simultaneously undermined and appropriated the ideals of second-wave feminism (in the 1960s and 70s).

“ remember distinctly Portman telling Zach Braff’s character that she was "weird” and then doing a silly little dance to illustrate her “weirdness.” Honestly? Anyone who telegraphs their so-called weirdness so outlandishly is not actually weird, they’re merely quirky enough to be vaguely interesting without having their own thing going on,“ says Jessica G. of Jezebel.

Post link

Does the world have sum against me cuz being on the internet and playing games r literally my only escape from my own thoughts rn who let the internet speed be so fcking slow too like you want me to kms or sum

Having a low-key comfy day

i think the most egregious example of the manic pixie dream girl trope was this play i but I just remembered seeing it, several years ago…

it was about this sad-sack guy driving across the country to try and reunite his old band for one last show

he’s accompanied by this girl who he was in the band with, back in the day… and he was in love with her then, and she’s cool & smart & funny & talks only to him for the entire play, even when the rest of the band joins him on the drive

& at the end of the play it turns out that she was a ghost the whole time, nobody else in the play could see or hear her, & the ‘last show’ he kept referring to is actually going to be her funeral wake bcs she died..

That her ghost had accompanied them on this trip bcs he was grieving & she wanted to help him let go of her…

which, you know, was a surprise & it was really emotional & legit the play was pretty good

But I just started thinking about it randomly…

And I keep being struck by the fact that the play only works if the entire audience is so used to the idea that a female character would literally only speak to the main male character for the entire length of a narrative.

Would only converse with him, interact with him, even when there were other people around.

That even as he talked about what he was doing next, she never discussed their future goals. She never touched any props or anyone other than him.

That nothing she did or said would genuinely have anything to do with herself as a person, except in the context of how he felt about her.

Theentire play hinges on the audience not expecting anything hinky about a female character who acts like that,

& most of the audience bought it, hook, line, and sinker.

even I did. there was genuine feeling of surprise in the room

and I just…

A woman can literally be an incorporeal ghost & as long as she is emotionally supportive of a man we see her as a fully realistically person

if that isn’t a sad indictment of how female characters get treated idk what is, honestly

she’s gone

he looks so dead and tired I want to fuck him

The boys, the girls, they all like Carmen

definitely the first one xx

Twee

Motifs: Falling in love, Jangly guitars, Hearts on sleeves

Values: Nerdiness, Sweetness, Romantic, Shyness, Carefree, Simplicity

Colors: Pastels, Bright colors

i want to fuck his smile

i just want to have a cathartic cry in his arms is that too much to ask for?

trying so hard to give him fuck me eyes but instead putting all my focus on understanding what the hell this guy is mumbling

its a feel like cassie, act like maddy typa week

Bite me

Trope:Manic pixie dream girl who falls for an older, soft-spoken nerd

for anon

Although it is my first attempt to anything other than Kuroko No Basket, but I hope this rant is reached out to the people who have found this particular anime as inspiring as I have.

Disclaimer: the animes I mentioned below, I don’t hate or despise them. So please don’t come defending that I am bashing them: because I am not. I used them to point out the difference between them and Barakamon

We all know these type of story: a genius male protagonist hits a slump, meets a quirky girl and then comes back to his field fully charged with his creative genius. Most of the time the hero is romantically involved with the heroine, and when the story is nearing resolution either the heroine is conveniently killed off or bonded forever with the hero. Barakamon follows the same bildungsroman pattern. But Barakamon is not like many anime belonging to the same type of story like Nodame Cantabile or Your Lie in April: because it reinvents the heroine from a quirky love interest to a real, living breathing human child: Naru Kotoishi.

Naru’s character have always perplexed me. She is a haywire child, nightmare to babysit for any person who is born and brought up in urban propriety, untamed, unfeminine, liberating. She represents the entire untamed naturality of the Gotou island, she is incorruptible hope. While everyone in the island appeared to be laid back and languid, she is the only one who is eccentric and unpredictable. When Handa arrives in the island, he is presented with the the two-faced persona: the out languidity of the island and the turbulent nature of the place that is seasoned dealing with nature’s unpredictability, in the tiny girl’s form.

So how does Naru fall into Handa’s narrative aside from literally barging into his new abode? Naru is actually everything Handa wished he had as a child: unbridled freedom, lack of controlling parents, playful and capricious. Handa was incubated into a controlled environment and molded into the fundamentalist calligrapher. Naru literally appears in a blue t-shirt and shorts with a length of rope coiled at her waist. That’s a wonderful allusion to “Wonder Woman” that was about to enter Handa Sei’s life. At the later episode, when Handa’s mother opposes how the countryside has “corrupted” his son’s refined character, we can also understand how Naru’s influence was a sort of Feminist invasion in the rigid, conservative setup of Calligraphy world. Handa’ s mother who is a good calligrapher isn’t a professional like her husband or son, thus it further proves the point that the field is male heavy space.

At the first episode, when his fundamentalist style was challenged, he lashed out and was forced to retreat. And who he finds facing him face to face? It’s Naru. At first she makes him uncomfortable, anxious and irritated but soon Handa comes to term with the child. Naru in her essence is the other side of artistry that is impulsive, bold and uncontrolled, something which is outside Handa’s comfort zone. In several episodes, Naru is seen spilling ink, tripping on the bottles and smearing ink in clear spaces, like on the hull of the boat where Handa was asked to write by Miwa’s father. This is a great allusion of Art being an uncontrolled living breathing organism which isn’t just there to please others with aesthetics; it stirs the souls and transforms. The sudden change in Handa’s style, from “well behaved penmanship” to “fuzzy experimental brush strokes” are great example of Naru’s influence over him. His words became simpler: “star”, “feather”, “utmost” “sea bream” and his style became totally eccentric. The last of “Barakamon” ‘s soundtrack is called “People learn from People” I think it actually alludes to Naru in the sense because she is the one who makes Handa face the limits of his art by challenging him physically and mentally.

So how Naru is different from the Manic pixie dream girls of the other similar animes? Both Megumi Noda of Nodame Cantabile and Kaori from Your Lies In April felt like the male fantasy of the slumped, socially awkward hero. Megumi who is outwardly perverted and downright lewd in many places is the caricature of Shinichi Chiaki’s rather prudish behaviour; as a reconciliation both end up as couples. Kaori in “Your Lie in April” is the textbook definition of “Manic Pixie Dream Girl” who is only there to motivate Kosuke Arima and disappear to the Death. Both of the women were musically prodigious and “muse-like” that brings the protagonist out of their roadblock. Both Megumi and Kaori play classical music which are not strictly dictated in the notations, and though it strikes Chiaki and Kosuke, they accept it as their path to sublimate. Naru is neither a prodigy in any artful sense, nor she is a sexual creature (or was seen with any romantic sense by the protagonist). Like any “Manic pixie dream girl” she makes the protagonist break out of his awkward shell through her eccentricity, but she does it with a perilous edge. Handa had to combat with all of his willpower to stand up to her antics in order to grow and mature. In this self-reliance boot-camp, all his previous identities, in the form of magazine articles, interviews and books gets torn out. The torn pages are then flown away as paper aeroplanes by Naru, as a symbolic gesture of “unlearning” in order to “learn” again.

The Muse figures in the other two animes are the comforting image of perfection which heroes of both Nodame Cantabile andYour Lie in April are trying to reach. Shinichi’s hurried and capricious playing of Mozart’s piano duet “Allegro Con Spirito” and Kosuke’s “Twinkle Twinkle 12 variations” are the attempts to touch the perfection of their respective muses. In both anime, Mozart plays a significant role in both animes in symbolizing the “perfect”, the “liberating” and the “sparkling”, something the hero must attain in the course of time. The theme of “reaching” in those animes are so apparent that “is my art/music reaching him/her?” is a quote which appears in almost every episode. Handa on the other hand never tries to “reach” Naru, who is the muse figure. In his struggle to find his “true self” she rather becomes the light of clarity through which he attempts breaks from his fundamentalist shell. In the end, Handa doesn’t become the paramount he had imagined he would; he gets rejected by the highly conformist industry which pushed him back because he was “too fundamental”: that sort of an anti-climatic ending to the Muse and Poet sort of narrative, and that’s where Naru’s significance lie. In art, there is nothing which is “perfect”, actually perfect is the enemy of good. In the end of Barakamon season 1, it is the “Good” that wins: Handa’s satisfaction with the calligraphy of the Doners’ names on wooden plank.

…

wow that’s a lot, now tags (although I have no evidence that they like Barakamon)

:@sidd-hit-my-butt-ham@yanderebakugo@kurokonbscenarios@kurokonobasket@kurokonoboisket@art-zites@idinaxye@sp-chernobyl@strawbe3ryshortcake@reservethemoon@rilnen@a-shy-potato@thirsthourdemon@animebxxch@edagawasatoru@akawaiishi-blog@reinyrei@chloe-noir@theswahn@ahobaka-trash@jeilliane@trashtoria @scarlettedwardsposts@quirkydarling@ghostieswaifu@levihan-freaks@hope-im-spirited-away@yves0809@marshiro1101 @bubziles @heartfullofknb@kit-kat57@akichan-th

-diary entry from 15.12.21

Overnight, I became the friend that will make personalised playlists for people’s birthdays, the friend that will ask you how you were at every silent moment in a conversation, because it’s a question that isn’t asked enough, the friend that won’t go a day without seeing you because she misses your face, despite the fact she didn’t know you before September, the friend that will get up and dance the second Ode To A Conversation Stuck In Your Throat plays, or Sex by The 1975, and will grab the hands of the closest person and get them to dance too, the friend that will knock first so you can speak, the friend that will talk to the Year 13s because they seem so scary despite being only a year older than you, the friend that walk you down to the coffee shop because you were going on your own, the friend that says hate is a strong word, but uses ‘love’ as easily as connectives, the friend that will ask you if you want to talk, because she’s there to listen, the friend that will be the first to apologise, the friend that will write poetry about you at 3am, and post it anonymously on Tumblr, the friend that confidence comes easily to, the friend with a god complex, despite hating herself, the friend that tells you that she dreamt of you the night before, despite it being a complete lie, the friend that will lie and cheat to get her own way, the friend that will manipulate and deceive just to remind everyone that she isn’t really thatfriend, because how could anyone have thatfriend? No one has her, really. She’s a Manic Pixie Dream Girl that’s trying too hard for the purpose of something that doesn’t even exist. She was none of these people four months ago. I wish I never had thatfriend. I think I’d kill her. She’d drive me mad.