#baudelaire orphans

Haven’t uploaded in a while so here’s a random wip of a drawing I’m working on :) anyone excited for the new series of unfortunate events on netflix???….. i know I am XD

Post link

In honor of Pride month (at least here in the US, I don’t know if other countries hold Pride the same month as us), I think it’s important to note the awesome LGBT diversity that either has been written into A Series of Unfortunate Events by Daniel Handler (who is bisexual himself) or ascribed to the series by so many people in this wonderful fandom.

Even before the Netflix series came out, Sir and Charles’s relationship was always heavily coded as gay. For one, even in 2000 when The Miserable Mill first came out, partner was already a term that had gained widespread popularity in same-sex relationships when the closest substitute for marriage for them was a civil partnership. The two of them also seem to have an awful lot of involvement in each other’s personal lives for business pairs, and Charles seemed to serve no actual role in the company except to stand alongside Sir. The biggest rainbow flag, however, was definitely in The Penultimate Peril when the two of them are sharing a hotel room with a single bed, Charles is in nothing but a bathrobe encouraging Sir to undress, and Sir utters the phrase “I just love the smell of hot wood”. I mean… it doesn’t get much clearer than that. Also the fact that the Netflix series made it canon without making any sort of deal of it whatsoever is just icing on top of the cake.

Next on the list is definitely Henchperson of Indeterminate Gender. Although in the book series, the character was less perceived by the children as nonbinary but overweight and confusing, the books still avoided using gendered pronouns. The Netflix series capitalizes on the increased attention to Count Olaf’s troupe and the VFD in general to show the Henchperson as canonically nonbinary, and very confident in their gender. They appear in both traditionally masculine and feminine clothes at fairly equal rates and yet their gender presentation or identity is never mocked once in the series and is respected by even the most despicable of villains. It is easy to throw LGBT characters in books or tv shows just for emotional fodder and to fall dangerously close to the “kill your gays” trope by making all LGBT characters discriminated against and marginalized, but showing an openly nonbinary character being accepted for who they are (which is admittedly a fairly awful person, they are in Olaf’s troupe) regardless of their gender is an amazing message to send to nonbinary children, teens and adults that they are not destined to be discriminated against and that we are quickly moving into a time when nonbinary identities are respected and understood.

And there are even more little references throughout the books and the series, Larry Your-Waiter having two mothers for example, that I honestly do not have the energy to go through completely and fully explain, that I hope you will just take my word for.

Then there are the openings made available in pretty much any series to interpret any of the characters as LGBT, and the ideas of a transgender-Isadora or lesbian-Jacqueline, or less commonly but my personal favorite, bisexual-Lemony-and-Olaf-as-bitter-first-loves-that-have-never-gotten-over-their-resentment-for-each-other-because-that-honestly-is-just-how-dramatic-both-of-them-are-as-people, have been pervasive in the community since the beginning. And I think it’s awesome that the series has not just permitted that, but encouraged it by openly showing LGBT characters whose sexualities and genders are actually discussed on screen or in book (looking at you, Harry Potter).

As an LGBT kid it was mindblowing to have what was even more a taboo topic then than it is now broached in a children’s novel, and as an LGBT adult it has been no different.

I’ve done my little analysis of the poem that Count Olaf recites just before he dies in The End, already, so I think it’s about time that I did analysis of the poem that Kit recites as well. Kit, as opposed to Olaf recites her poem in its entirety, but I’ve included the poem here as well just for convenience’s sake:

The night has a thousand eyes,

And the day but one;

Yet the light of the bright world dies,

With the dying sun.

The mind has a thousand eyes,

And the heart but one;

Yet the light of a whole life dies,

When love is done.

Kit reads her poem aloud first, and it’s a much less straightforward poem than the one that Count Olaf reads - it has a lot of symbolism and poetic language and the meaning isn’t stated directly within the text - but I think when it’s broken down it can be understood quite easily and it provides a great deal of insight into both her and Count Olaf, and the VFD as a whole as well.

The first thing a ASOUE fan will take note of in this poem, is obviously the eye connection. The passage immediately preceding this poem is of the Baudelaires’ reflections on the VFD eye and all the places they’ve seen it and all the people they’ve seen sport it and wondering whether the VFD is truly good or evil, so there’s definitely a point to be made about a poem about eyes coming directly after a passage about eyes, but I think in that obvious interpretation, readers often miss the subtlety of the poem.

Put quite simply, it’s a poem about not overthinking life and allowing yourself to be guided by your feelings. “The night has a thousand eyes” as opposed to the single eye (the sun) of the day, but the day is what is the brightest of them all and even the thousand eyes of the night sky do not come close to illuminating the world as well as the sun does. The mind likewise is capable of producing a million thoughts an hour, self-doubts, observations, second guesses, and it can be easy to be guided only by your head in this world and pick the rational over the emotional, but life only matters when you are happy - when you are guided by your heart. Rationality will always win in terms of quantity, but love is what lights up your world.

Although there is a break between when the original conversation occurs and when Kit recites the poem, it comes at the reunion of Kit and Olaf for the first time in assumingly a long time. Olaf kisses Kit, and says he would do that one last time, Kit says she’s not going to forgive him because one good act doesn’t make up for all he’s done wrong, and Olaf says that he doesn’t want forgiveness - he never apologized. Then Kit touches his tattoo.

The poem seems to be Kit’s response to Olaf’s tattoo and his experience with the VFD - perhaps both of their experiences, after all we know that Kit was instrumental in the murder of Olaf’s parents. She recites to him while reminding him of his lifetime bond of hatred to the VFD, that love is powerful and love is what makes life worth living, not all the regrets and hopes and alternate fantasies of a world we could have made. Olaf says he never apologized to Kit, and the Baudelaires, and he says it in a way that shows he has no desire to now. Olaf refuses to apologize for his actions because he feels they are rooted in vengeance. He is still mad at Kit and the Baudelaires for the harm they have caused him, either directly or indirectly, and in his own way grieving over the loss of his parents. He is angry that they were killed and that it could have been prevented and he is stuck in a mindset that demands retribution - but the thing about retribution is that it can never truly exist because there is no way to truly avenge your parents deaths as long as they are still dead. Olaf is stuck in his head imagining a fair world where none of this ever happens and he is so stuck in that mindset that he attempts to impose that justice onto the world in his own messed up ways. He loves Kit, it is clear, but he is so driven by anger that he does not let himself love her and does not let himself move on. He has fueled himself by anger and not love for so long that the light in his life has died and he is left a bitter, angry wreck of a man.

There’s a lot we can draw from this poem and this analysis of Count Olaf that Kit makes and a lot of it has to do with forgiveness and moving on from trauma. Count Olaf was never able to move on from his parent’s murder and in the end it destroyed him. He never forgave the people who hurt him and as a result he carried that weight and anger around with him until it destroyed him. This is not to say that people have an obligation to forgive their abusers, to love unconditionally and to let everything go, because there are some things you should hold onto and there is some anger that is justified, but anger is an emotion not a characteristic and is but one of a thousand little things in our lives that can distract us from what really matters in life. You can’t force yourself to live in the past because no matter how tightly you cling to it, it’s already gone and eventually you have to move on or everyone else is going to move on from you. The Baudelaires in the passage before this are so preoccupied by the thousand eyes that they’ve seen throughout their amazing adventures and interactions with the VFD and all the questions that they haven’t answered, that they temporarily lose sight of the one thing that matters. But in the end as they bring Kit’s baby into the world, and life begins anew, they forget their anger and their resentment towards all the injustice they are faced and towards the man who caused it all, laying dying behind them, alone and forgotten, they allow their hearts to guide them and they are unburdened by the past for the first time in a long time. Trauma is a healing process, but it is one that takes constant forward effort, and in this moment - in this crossroads where Olaf and the Baudelaires diverge for the last time - they chose to move on and accept that justice and answers aren’t always doled out evenly in the world and that sometimes you have to just let your heart guide you forward.

I scroll through the ASOUE tag on Tumblr at least once a day and when I do I see dozens upon dozens of posts of people asking for season 3 of the Netflix adaptation of ASOUE to answer all their questions. Specifically, I see people asking about whether we’ll find out what’s in the sugar bowl or why the Duchess of Winnipeg gave Lemony Snicket the ring in the first place or whether Count Olaf actually did kill the Baudelaire parents, the list goes on.

But as I read these posts and I reread the books I have to say… I don’t want to find out the answers to everything. And I really hope the Netflix series doesn’t answer them all. Because that’s probably the greatest lesson of all in the stories: that life doesn’t have all the answers and is often incomplete and unfulfilling.

As the Baudelaire children have their grand adventures and seek escape from Count Olaf and his troupe of horrors, they are plagued with dozens of questions that seem to follow them throughout the story: Why does Count Olaf do this? What does the eye mean? What does VFD stand for? Why did their parents lie to them about all this? What is in the sugar bowl?

And for the most part, their questions are answered. It is a story after all and stories have to have some sort of resolution. But as our questions are answered even more questions appear. Even with the resolution of A Series of Unfortunate Events and The Beatrice Letters and The Unauthorized Autobiography, we still do not know much of anything about the VFD or have answers to most of the in-series questions left unresolved at the end of The End.

But that’s the way life is. Life doesn’t answer all your questions in a neat little bundle at the end. Life isn’t beholden to the same conventions as literature - because as much as we’d prefer it not to be so, life isn’t a story it’s an ongoing journey paved by the questions we ask and receive along the way. And much like a dissatisfying answer to a long-held question, it ends when it ends, whether we’ve resolved all of our sub-plots or not. A Series of Unfortunate Events purposefully doesn’t answer all of the questions by the end of the series because life never answers all the questions and if the Netflix series were to attempt to change that - to fix it - as I’ve seen people suggest, then I think that would do a great disservice to the thematic integrity of the series and the lessons Handler has taught through this book in general.

One thing that A Series of Unfortunate Events does really well is that it establishes very early on to a quite young audience that sometimes people don’t mean it personally when they hurt you, but that doesn’t excuse their behavior.

Take Mr. Poe for instance: in every single encounter the Baudelaire orphans have with him, he messes everything up. He consistently puts the children in dangerous situations just because it’s convenient for him, he never listens to what the children actually have to say, and he refuses to be held accountable for his own mistakes, thereby dooming himself to make them over and over again.

If you divide it up evenly, Mr. Poe is just as responsible for the children’s ill fate as Count Olaf because for every single book in which he’s involved, and up through The Carnivorous Carnival in the Netflix series, he is capable of righting the situation and saving the children and he still decides to save his own behind rather than helping the children who are in dire need of an adult figure they can trust. Desmond Tutu famously said that “if you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor”.

And yet, Handler draws a distinctive line between Mr. Poe and Count Olaf in the series because one truly is worse than the other. Mr. Poe doesn’t mean to harm the children, and genuinely does care about their wellbeing, even if he is awful at doing so. He is always appalled when Count Olaf is actually revealed at the end and he does want the children to be safe. Count Olaf on the other hand actually hates the children and means to cause them harm.

The series draws the same distinction between Charles and Sir in that regard and Jerome and Esme, as well. It makes the point that people hurt each other and do harm in the world for all sorts of reasons and very rarely is it personal - that we shouldn’t take it personally when people are bad because adults are fallible too and sometimes they make mistakes without thinking. But even more so, the series makes the point that unintentionality does not excuse the harm that they do. Just because someone doesn’t hate you and that someone didn’t mean to harm you doesn’t mean you are obligated to forgive them or be understanding of their position. So often in this world people make excuses for their behavior, saying they didn’t mean to do something or they didn’t understand the effect it would have or they just weren’t listening and we’re expected to accept their apology and move on because we’re told intent means everything.

But the thing is, intent isn’t everything. Intent is only half the battle and our actions always have consequences, regardless of whether we like those consequences or not. Ignorance is not an excuse for inaction because it is our responsibility in the world as citizens of the world to be conscious of the effect our choices could have on others. The Baudelaire orphans never forgive Mr. Poe, and in The Penultimate Peril when Mr. Poe approaches them and offers them help and offers to take them to their next home, they refuse his help and their refuse his apology because his intentions in that instance don’t matter because he created great harm in the world and just because he didn’t foresee it doesn’t mean that he couldn’t have. This follows the same vein as excusing someone’s behavior because it was rooted in deep trauma or mental illness or justified revenge - the reason why someone did something wrong doesn’t matter, they still did something wrong and they need to face up to their crimes.

It was an important message then, but I think it’s an even more important one now in the political climate that we live in. There are so many people in this world right now who want to cause harm: neo-Nazis, the alt-right, homophobes, transphobes, racists, sexists, and we have an administration that actively takes delight in causing harm to oppressed people as long as it stands to benefit them in some financial way. They know they are hurting people and they continue to do so anyways so long as it makes them more comfortable. These are the Count Olafs of the world.

But then there are the ignorant people that support Trump and his administration, that do racist things like calling the cops on black people just because they look “suspicious”, or use their religion as an excuse to justify discrimination, and simply regurgitate everything they’ve been told by others just as ignorant as them about the way the world ought to work, and those are the people who pave the way for the Count Olafs of the world. It is easier to excuse their bad behavior because they really don’t mean for what they do to cause harm - most of the time they genuinely think they’re doing the right thing - but their actions have just as big of consequences as the actions of the Count Olafs. The children never would have ended up in Count Olaf’s clutches time and time again if Mr. Poe hadn’t put them there. The Count Olafs are worse, and it’s important to recognize the difference between intended harm and unintended harm, but we have to hold the Mr. Poes of the world accountable too, because ignorance is just as much a choice as malice.

I’ve always loved the poem that Count Olaf recites to Kit just before he dies in The End, and by love of course, I mean I bawl my eyes out every single time I read it. He only reads the last stanza aloud, but here is the poem in its entirety:

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

But they were fucked up in their turn

By fools in old-style hats and coats,

Who half the time were soppy-stern

And half at one another’s throats.

Man hands on misery to man.

It deepens like a coastal shelf.

Get out as early as you can,

And don’t have any kids yourself.

- Philip Larkin

Obviously, we can understand why Handler didn’t want to include explicit profanity in a book written for middle grade children, but I really do love the fact that the first two stanzas are left unsaid and the reader, if interested actually has to go and research them and find them out for themself, because that is one of the points of the poem and one of the points of the series - that people don’t tell you the whole story and that things are always much more complicated than they seem - even things that seem like black and white morality are always so much more complicated.

Yes, your parents mess you up and ruin you, just like the Baudelaires find out in The Penultimate Peril and The End that their parents were not perfect and possibly even are the reason why all this horror has been happening to them, but the story is more complicated than that and the Baudelaires (and the readers) are left for themselves whether or not they want to leave it be - just read the last verse - or they want to explore for themselves and maybe not like what they find.

Ever since The Austere Academy, the Baudelaires have been told that the VFD was a noble organization and filled with volunteers that will help them, but the noble side of the VFD also produced lots of people who did horrible things: the Baudelaire parents, Jerome Squalor, Lemony and Kit Snicket. The VFD taught them to follow blindly and so they blindly followed and they accepted authority at its face value and as a result they became corrupted by those in power.

Ultimately, this poem is about the cycle of abuse and misery in this world. “Man hands misery onto man”, we inherit our trauma from each other and we create our own demons out of the demons that have been fed to us, and we tell ourselves that we won’t do the same, but we indubitably will. To be human is to be messed up, and the kindest thing you can do in life is to not bring any more people into the world.

But particularly interesting to me is Count Olaf’s recitation of the poem. Because in the passage, he’s not reciting it to to the Baudelaires, he’s reciting it to Kit, as she gives birth on a coastal shelf. On a personal, theoretical level, I have always used this as evidence that Beatrice II was Count Olaf’s biological daughter, but also it acts as a symbol of Count Olaf’s journey - he is an awful, awful man who has hurt the children put into his care time and time again and probably messed them up on some psychological level for the rest of their lives, but he too was messed up and turned out by the world by the people who raised and shaped him, and ultimately the root of evil goes back much further than we’d like to think. We’d like to think that Count Olaf is just a cruel, uncaring man who acts the way he does out of cold-blood, but the world doesn’t work that way and he’s trying to tell Kit that he is the way he is because of his history, that he was jaded by the world young and he never managed to escape, and that he’s not actually a bad man. But even as he recites the poem, he laughs, because he recognizes his complicity in everything - he has handed down his misery as well and he has brought a child into the world against all warning. It is him recognizing his crimes and his irony, something the Baudelaires and Kit never thought he would do.

It also serves a larger purpose in that Count Olaf has always been described as unintelligent and dismissive of intellect and reading and the orphans have always maintained that if a person is well-read they must be a good person and that reading is what makes people good. Because Count Olaf is not good, and yet he is able to recite an obscure poem - written by a librarian, no less - in the blink of an eye. Throughout the entirety of The End, Count Olaf has defied his stereotype by proving to be intelligent and capable of empathy and eschewing everything we thought we knew about him. Things are always more complicated than they seem and go back further than you’d like to think, and the world itself is a messed up place - a conundrum of esoterica, if you will - and defies any pithy explanation you might try and force upon it.

The End, the final book in the ASOUE series deviates substantially from the twelve previous books in the series because it doesn’t follow the traditional narrative that the other books adhere to at all. In the other books it always goes something like the orphans wind up in a new place, they meet someone they think can be an ally to them and then that person winds up either dying or being ineffectual or compromised in some sort of way by the arrival of Count Olaf and the orphans are forced to flee from danger, hoping along the way that eventually when all this is said and done they can find some nice quiet place to live, where they aren’t constantly in danger.

In The End, by contrast, they arrive with Count Olaf to a new location with people who are quick to eliminate Olaf as a danger for them and attempt to bring them into their peaceful happy lives. In actuality, the story could have ended there. They had no real reason to go against the rules of the island or question the authority of Ishmael, and none of the islanders or Ishmael were rude to them at all. The only reason they returned to Count Olaf and rebelled against the island is because they thought it was boring. After twelve books of adventure after adventure, trying to escape danger time and time again, the Baudelaire orphans realize that they actually don’t know how to exist in safety.

Which seems to defeat the entire point of the Baudelaire’s quest for safety in the other twelve books, but I think it’s an important point about what happens after the worst has already happened. The Baudelaires have reached safety after so long, but they’re so used to not being safe that they don’t even know how to be comfortable in a safe environment. They’ve wanted this for so long but once it finally came they realized that they were never prepared for it.

This is a common trope in the lives of people who have survived insurmountable trauma. They spend the duration of their trauma clinging to this hope of a better life outside of it and imagining a perfect world where they are safe all the time, but then when they escape they realize that they’ve become so used to their trauma world that the regular world seems completely foreign to them. Furthermore, once they’ve physically escaped their trauma they’re left with the second, more daunting task of emotionally escaping it and moving on.

The End isn’t an escape from danger in the traditional sense, but more a look into what we do once we have escaped danger and how danger eventually escapes us. Most books end when the danger has been resolved, the plot has been fulfilled and everything has been worked out. But ASOUE shows that even after the danger has been resolved, everything will never be worked out completely. Life isn’t a book with a simple exposition, climax and resolution, it is a series of unfortunate events and even after we’ve conquered our demons we still have to live knowing what happened to us and where and when and that antagonist is a much harder one to defeat.

One of the things the ASOUE series does particularly well is that it subverts the narrative that is all too often perpetrated in children’s literature (and adult literature, let’s be honest), that karma is a real operating force in the world and that we all are fated to have good or bad things happen to us depending on how well we act in the world. ASOUE shows that that is not at all true. Sometimes good things happen to good people and bad things happen to bad people - but it’s all random happenstance, and not some cosmic destiny for good people to be rewarded and bad people to be punished.

At the beginning of the series we get these three lovely, perfect children who as far as we know have done nothing wrong and are incredibly polite and kind even in the face of evil. Even though Snicket warns the audience that nothing good will happen to the orphans, kids know that good people always have happy endings so it’s brushed off as a depressing narrator who is simply describing the trials and tribulations that the Baudelaire orphans will face throughout the book. But when we get to the end and the orphans have solved the mystery, escaped from their captor and have proven themselves worthy of respect and a happy ending, they are defeated again through random happenstance and left more or less where they started. They have done nothing to deserve evil, but evil has been forced on them anyways.

One of the problems with perpetuating the idea that karma is an active force in the world is that if good people are always rewarded and bad people are always punished, then good people who consistently do good thing with no payoff are left feeling like they’re bad people because apparently if they were actually good they would receive some kind of retribution. But the world doesn’t work that way. Sometimes bad things happen to good people and good things happen to bad people and that’s just the way the world is.

A Series of Unfortunate Events does an incredibly good job of explaining the concept of a random universe - where things just happen and nothing really matters in the long run because everything will just turn out how it turns out regardless. It’s an absurdist (like happier nihilism) take on the world, and I find it interesting that such an obscure and defeatist philosophy is able to be introduced so easily to children as young as I was when I read the series. But then again, one of the things ASOUE does best is not being condescending to children and engaging with them about the real world - recognizing that they are smart, functioning beings capable of understanding the world - and teaching them such a hard lesson about life so early on without making it overly depressing is something that I rarely see talked about in praise of ASOUE, and something that I think is worthy of commendation.

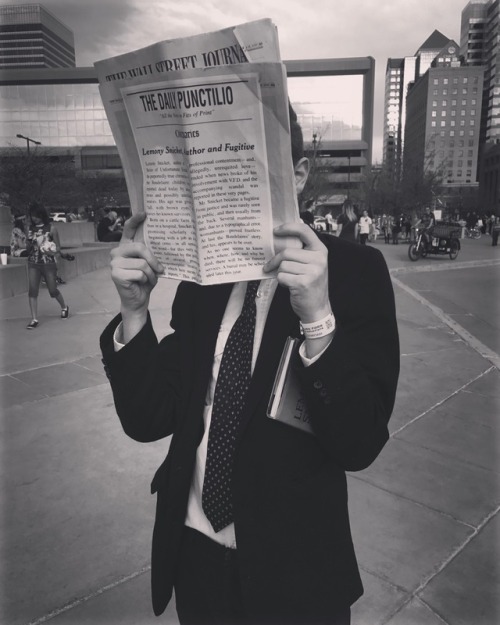

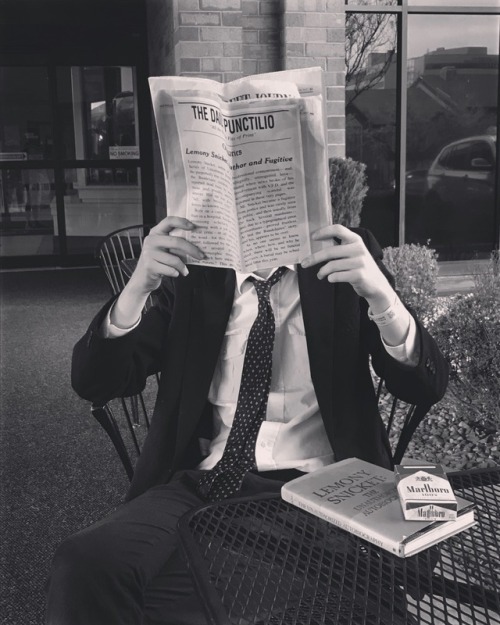

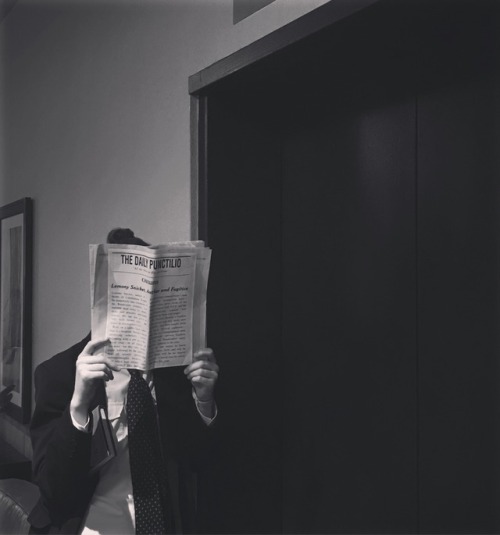

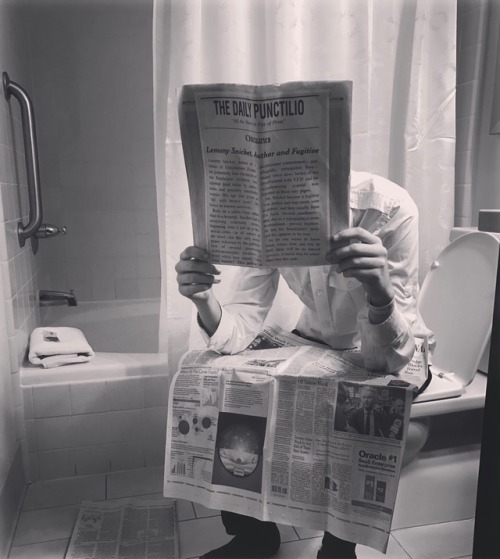

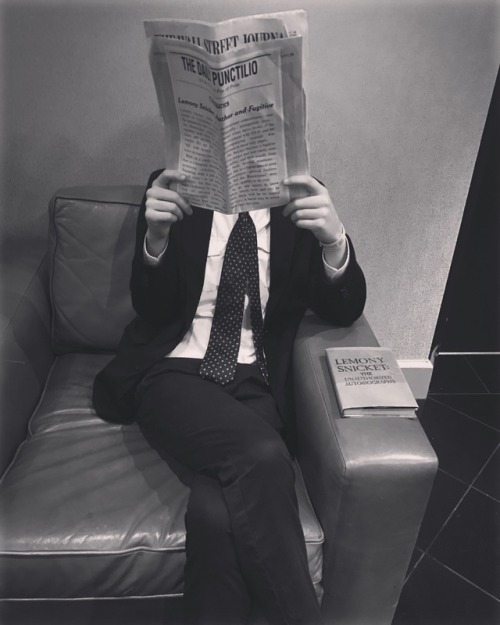

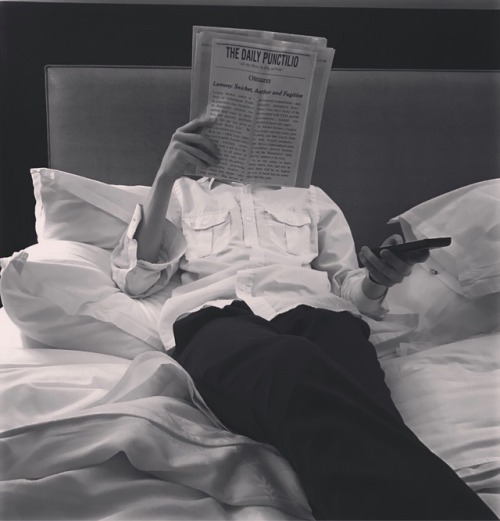

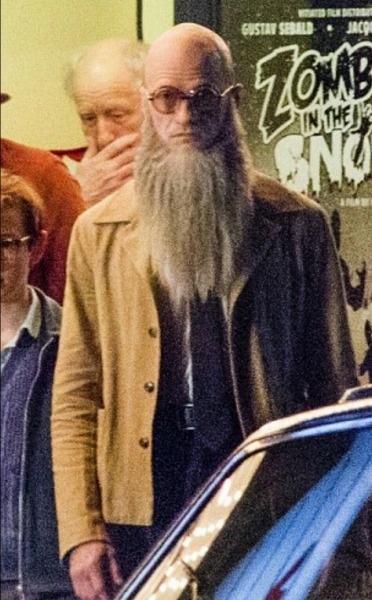

I went to Salt Lake City FanX Comic Con as Lemony Snicket and had a little too much fun.

I call this “Lemony Snicket being inconspicuous, a word which here means, ‘blending in with society while attempting to avoid capture’ in various locations.”

Post link

First look at Lemony Snicket, The Baudelaire Orphans, Uncle Monty, and Stephano, an Italian man, in The Reptile Room Part 1 & 2

Post link

will olaf and minions ever end. will i be forced to live the rest of my life occasionally seeing olaf and minions

Said the Baudelaire children.

As they experienced a series of despicable unfortunate events