#contemplation

When eating dinner, you must consider every possible angle before shoveling food into your mouth.

Only then may you burp.

Why being a Judith Anderson fan is life-enhancing

This week finds me contemplating the myriad ways in which being an admirer of Dame Judith Anderson (pictured looking elegant in 1966) enriches my life. Her work introduces me to or encourages me to revisit landmark plays and films (most notably MedeaandHitchcock’s Rebecca). Her performances inspire my creative writing (just ask @thisismrsdanvers how long I’ve been working on a Mrs Danvers-themed short story!). Her determination and incredible work ethic are incredibly motivating when I find myself procrastinating (’Work hard, and if it is to be, it will come,’ she once remarked sagely.) I’ve rediscovered the beauty of Daphne du Maurier’s prose, thanks to Judith, and discovered Robinson Jeffers’ astonishing poems (her readings of them are *sublime*).

On a more personal note, I’ve learned to accept myself more since becoming a fan. I avoid talking about Judith’s personal life on this blog out of respect, but what I will say is that I now feel more comfortable in my own skin, thanks to her influence. She’s taught me to be more resilient and to care less about what other people think about me (after all, she made a tremendously successful career for herself despite not conforming to the glitzy Hollywood stereotype). I know that you can be beautiful without looking like a Barbie doll. I know that being unmarried and not having children doesn’t make anyone a failure. I know that a woman can achieve truly amazing things when she puts her mind to it. And when all else fails, I know I can cheer myself up by looking at this photo;-)

Most of all, I’m grateful to Judith for bringing wonderful, life-enhancing friendships into my world (with @thisismrsdanvers,@satedanfire,@ralphsmotorbike and others). We can’t get to know the great lady herself, but those friends and I share a sincere appreciation of her acting talents and strength of character.

Well, I’ve written far more than I’d intended. Bonus points if you’ve got to the end of this! How does being a fan of Judith enrich your life? I’d love to know.

Post link

Vincent Horn exploring the development of technology, geek culture and Buddhism.

I love dramatic portraits the best!

@iamenzolarocca #dramaticportrait #drama #blackandwhitephotography #malemodels #model #fitness #guru #soul #contemplation

https://www.instagram.com/p/BryN4M4gIxP/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=nmy25g5d05t

Post link

I love dramatic portraits the best!

@iamenzolarocca #dramaticportrait #drama #blackandwhitephotography #malemodels #model #fitness #guru #soul #contemplation

https://www.instagram.com/p/BryN4M4gIxP/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=1n840unr1xajx

Post link

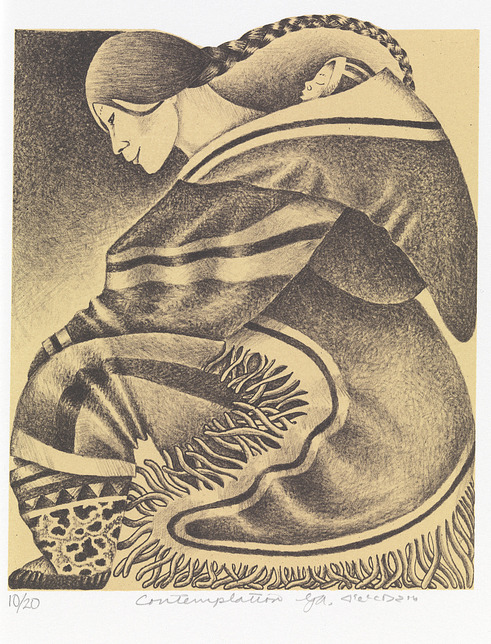

germaine arnaktauyok, “contemplation,” 2005-6, lithograph

https://www.inuitartfoundation.org/profiles/artist/Germaine-Arnaktauyok

Post link

Into the garbage chute, trash lord.

Based on this comic by@kayurka

Rey - @commandercait[fb][ig]

Kylo Ren - @arkadycosplay[fb][ig]

Photographer - @lady-lucrezia[fb]

This really is hard to decide…. Perhaps if I recycle him, he’ll become good?

#CuriousRey #RecyclingKyloRen

Post link

Excerpts from this luminous Easter meditation by Fuller Studio:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FynTFKdSGjo

Post link

I enjoyed this book so much, I temporarily unhinged my regarding obsessive compulsion and scoured it clean of my favorite quotations. As a caveat, I don’t have the page numbers because I read it on a kindle. But Google should help you find any page if it should ever “kindle” your interest to quote this book in a paper. Enjoy.

…the undertaking that my father did had less to do with what was done to the dead and more to do with what the living did about the fact of life that people died

Thus, undertakings are the things we do to vest the lives we lead against the cold, the meaningless, the void, the noisy blather, and the blinding dark. It is the voice we give to wonderment, to pain, to love and desire, anger and outrage; the words that we shape into song and prayer

To undertake is to bind oneself to the performance of a task, to pledge or promise to get it done. And when he died, it seemed I’d done just that. I had told I would write the book someday. The book I had in mind would be for poets, who had their questions about the things we do. Or maybe for people who read what poets wrote, and wondered what they meant, or wanted more. I think what my father had in mind was a book for dismal traders, funeral type’s – for men and women who dress in black, and work the weekends and the holidays, who line the cars up and lay the bodies out, who rise and go out in the dark when someone dies and someone calls for help

…it is also true that the dead don’t care. In this way, the dead I buy and burn are like the dead before them, for whom time and space have become mortally unimportant. This loss of interest is, in fact, one of the first sure signs that something serious is about to happen. The next thing is the quit breathing. At this point, to be sure, a gunshot wound to the chestorshock and trauma will be more ink than a CVA or ASHD, but no cause of death is any less permanent than the other. Any one will do. The dead don’t care.

Knowing is better than not knowing, and knowing it is you is terrifically better than knowing it is me. Because once I’m the dead guy, whether you’re OK or he’s OK won’t much interest me. You can all go bag your asses, because the dead don’t care. Of course, the living, bound by their adverbs and their actuarial, still do. Now, there is the difference and why I’m in business. The living are careful and oftentimes caring. The dead are careless, or maybe it’s care-less. Either way, they don’t care. These are unremarkable and verifiable truth.

And I am sorry to be repeating myself, but this is the central fact of my business – that there is nothing, once you are dead, that can be done to youorfor you orwith you orabout you that will do you any good or any harm; that any damage or decency we do accrues to the living, to whom your death happens, if it really happens to anyone. The living have to live with it. You don’t. Theirs is the grief or gladness your death brings. Theirs is the loss or gain of it. Theirs is the pain and the pleasure of memory. Theirs is the invoice for services rendered and theirs is the check in the mail for its payment.

I have no more stomach for misery that the banker or the lawyer, the pastor o the politico – because misery is careless and is everywhere. Miser is the bad check, the ex-spouse, the mob in the street, and the IRS – who, like the dead, feel nothing and, like the dead, don’t care.

We are forever dying of failures, of anomalies, of insufficiencies, of dysfunctions, arrests, accidents.

We are always waiting. Waiting for some good word or the winning numbers. Waiting for a sign or wonder, some signal from our dear dead that the dead still care. We are gladdened when they do the outstanding things, when they arise from their graves or fall through their caskets or speak to us in our waking dreams. It pleases us no end, as if the dead still cared, had agendas, were yet alive.

But the sad and well-known fact of the matter is that most of us will stay in our caskets and be dead a long time, and that our urns and graves will never make a sound. Our reason and requiems, our headstones or High Masses, will neither get us in nor keep us out of heaven. The meaning of our lives, and the memories of them, belong to the living, just as our funerals do. Whatever beings the dead have now, they have by the living’s faith alone.

And the rituals we devise to conduct the living and beloved and the dead from one status to another have less to do with performance than with meaning. In a world where “dysfunctional” has become the operative adjective, a body that has ceased to work has, it would seem, few useful applications … a person who has ceased to be is as compelling a prospect as it was when the Neanderthal first dug holes for his dead, shaping the questions we still shape in the face of death: “Is that all there is?” “What does it mean?” “Why is it cold?” “Can it happen to me?”

The bodies of the newly dead are not debris nor remnant, nor are they entirely icon or essence. They are, rather, changelings, incubates, hatchlings of a new reality that bear our names and dates, our image and likenesses, as surely in the eyes and ears of our children and grandchildren as did word of our birth in the ears of our parents and their parents. It is wise to treat such new things tenderly, carefully, with honor.

…the meaning of life is connected, inextricably, to the meaning of death; that mourning is a romance in reverse, and if you love, you grieve and there are no exceptions – only those who do it well and those who don’t.

The thing about the new toilet is that it removes the evidence in such a hurry. The flush toilet, more than any single invention, has “civilized” us in a way that religion and law could never accomplish. No more the morning office of the chamber pot or outhouse, where sights and sounds and odors and reminded us of the corruptibility of flesh. Since Crapper’s marvelous inventions, we need only pull the lever behind us and the evidence disappears, a kind of rapture that that removes the nuisance”

This is also why the funerals held in my funeral parlor lack an essential manifest – the connection of the baby born to the marriage made to the deaths we grieve in the life of a family. I have no weddings or baptisms in the funeral home and the folks that pay me have maybe los sight of the obvious connection between the life and the death of us. And how the rituals by which we mark the things that only happen to us once, birth and death, or maybe twice in the case of marriage, carry the same emotional mail – a message of loss and gain, love and grief, things changed utterly.

And just as bringing the crapper indoors has made feces an embarrassment, pushing the dead and dying out has made death one.

We parent the way we were parented.

When we bury the old, we bury the known past, the past we imagine sometimes better than it was, but the past all the same a portion of which we inhabited. Memory is the overwhelming theme, the eventual comfort.

But burying infants, we bury the future, unwieldy and unknown, full of promise and possibilities, outcomes punctuated by our rosy hopes. The grief has no borders, no limits, no known ends, and the little infant graves that edge the corners and fencerows of every cemetery are never quite big enough to contain that grief. Some sadnesses are permanent. Dead babies do not give us memories. They give us dreams.

And I would never charge more than the wholesale cost of the casket and throw in our services free of charge with the hope in my heart that God would, in turn, spare me the hollowing grief of these parents.

The poor cousin of fear is anger. It is the rage that rises in us when our children do not look both ways before running into busy streets. Or take to heart the free advice we’re always serving up to keep them from pitfalls and problems. … It is the war we wage against those facts of life over which we have no power, none at all. It makes for heroes and histrionics but it s no way to raise children.

And there were mornings I’d awaken heroic and angry, hungover and enraged at the uncontrollable facts of my life: the constant demands of my business, the loneliness of my bed, the damaged goods my children seemed.

War rages in the usual places, hunger whittles through whole populations. Plagues decimate the culture and the sub-cultures. The dead are everywhere. In such a world it is hard to work up sympathy for a white man with tenure, the lion’s share of his pension left, visitation rights, his health, his job.

Heartbreak is an invisible affliction. No limp comes with it, no evident scar. No sticker is issued that guarantees good parking or easy access. The heart is broken all the same. The soul festers. The wound, untreated, can be terminal.

Thus we regard funerals and the ones who direct them with the same grim ambivalence as those who deliver us of hemorrhoids and boils and bowel impactions – Thanks, we wince or grin at the offer, but no thanks.

As always, the anomalies prove the rule

And there are elements of the revered clergy who have come to the enlightenment that, better than baptisms or marriages, funerals press the noses of the faithful against the windows of their faith. Vision and insight are often coincidental with demise. Death is the moment when the chips are down. That moment of truth when the truth we die makes relevant the claims of our prophets and apostles. Faith is not required to sing in the choir, for bake sales or building drives; to usher or deacon or elder or priest. Faith is for the time of our dying and the time of dying of the ones we love.

But only by faith do the dead arise and walk among us or speak to us in our soul’s dark nights.

Faith is for the heartbroken, the embittered, the doubting, and the dead. And funerals are the venues at which such folks gather.

Most of the known world could not be paid enough to embalm a neighbor on Christmas or stand with an old widower at his wife’s open casket or talk with a leukemic mother about her fears for her children about to be motherless. The ones who last in this work are the ones who believe what they do is not only good for business, and the bottom line, but good, after everything, for the species

Eastern though has always favored fire as a purifier

And for every home made memorable by death, dozens are made memorable by the lives that were led there utterly unscrutinized by the wider world – lives lived out at a pace quickened only by the ordinary triumphs of daily life: good gladiolas, the well-shoveled walk, the mortgage payments made, the kids through college. Or by the ordinary failures: the bad marriage, the broken water main, trouble with the tax man, the sons and daughters who never call. We know our neighbors and our neighbors’ business here. It is the blessing and the curse of the small place. It is getting better lately, and getting worse.

But somehow, memories of the dead seemed more accessible, the dead themselves not so estranged.

I often think about this schizophrenia, how we are drawn to the dead and yet abhor them, how grief places them on pedestals and buries them in graves or burns the evidence, how we love and hate them all at once; how the same dead man is both saint and sonovabitch, how ‘the dead’ are frightening but our dead are dear. I think funerals and graveyards seek to mend these fences and bridge these gaps between our fears and fond feelings, between the sickness and the sadness it variously awakens in us, between the weeping and dancing we are driven to at the news of someone’s dying. The man who said that all deaths diminish me was talking about the knowledge at the edges of every obit that it was not me and someday will be.

…I have come to believe that what he sensed as a baby, what he knew as a boy, what he knows as a man is that we die. On this account he is absolutely right. If his wariness seems acute, intense, at times neurotic, it could just as easily be called a gift. Perhaps he sees the ghost in the mirror. Or feels the chill in every touch. Perhaps he hears the imp more clearly. Or sniffs the rotting with the sweet.

I had this theory. It was based loosely on the unremarkable observation that the hold are always looking back with longing while the young, with the same longing, look ahead. One man remembers that the other imagined. … My theory held that we could calculate the precise midpoint of life by an application of these none too ponderous truths. And knowing the precise midpoint would, of course, give me the Thing Most Unknown: the day I would die. Knowing the middle, the end could be known. It was algebra: x’s and equal signs, a’s plus b’s.

If the past is a province the aged revisit and the future is one that the child dreams, birth and death are the oceans that bound them. And midlife is the moment between them, that frontier when it seems as if we could go either way, when our view is as good on either side. We are filled less with longing than with wonder. We fear less and worry more. These are only a few of the symptoms. The old write memoirs, the young do resumes. In midlife we keep a kind of diary that always begins with a discussion of the weather.

The present is where we live, equidistant from our birth and death.

There is about midlife, a kind of balance, equilibrium – neither pushed by youth nor shoved by age: we float, momentarily released from the gravity of time. We see our history and future clearly. We sleep well, dream in all tenses, wake ready and able.

Walking upright between the past and future, a tightrope walk across our times, became, for me, a way of living: trying to maintain a balance between the competing gravities of birth and death, hope and regret, sex and mortality, love and grief, all those opposites or nearly opposites that become, after a while, the rocks and hard places, synonymous forces between which we navigate, like salmon balanced in the current, damned sometimes if we do or don’t.

Unwilling to let go or get out of the way or let Nature take its course, we lobby for more and more ‘options.’ Thus, what has always seemed offensive about suicide – that it seemed to subvert Nature’s intention, or God’s intentions, whomever’s in charge – is rendered acceptable, indeed, preferable, at the other end of life, by the user-friendly doctrines of Control and Choice (as in birth control and reproductive choice), which seem to suggest that, when we can, we should play God or fool Mother Nature.

More subtle and more troubling are the truths that wars have been waged for greed and glory rather than humanitarian causes, abortion has been used in the service of sexist, racist, and classist agendas, and euthanasia has been, at times, the thin veil over genocide, abuse, neglect, and homicide. All of our “choices” have not been good ones.

Thus, the great divisions of the last half century and the next half century seem based on the contemplation of Life and Death: when one becomes the other and under whose agency. The advance of our technology is coincidental with the loss of our appetite for ethical questions that ought to attend the implications of these new powers. We have blurred the borders between being and ceasing to be by a technology that can tell us How It Works but not What It Means. Nor do we trust our instincts anymore. If we sense something is Wrong, we are embarrassed to say so, just as we are when we sense it is Right. In the name of diversity, any idea is regarded as worthy as any other; any nonsense is entitled to a forum, a full hearing, and equal time. Reality is customized to fit the person or the situation. There is yourreality and myreality, the truth as they see it, but what is real and true for us all eludes us. We frame our personal questions in terms of the legal and illegal, politically correct or incorrect, function or dysfunction how it impacts our self-esteem, or puts us in touch with our feelings, or bodes for the next election or millage vote or how the markets will respond.

Perhaps it is our natureto die, not our right. Maybe we have the abilityto kill, to make thing dead, even ourselves, but we haven’t the right. And when we exercise that ability, in the name of God (as we have done in war), or of Justice (as we have done with capital punishment), or of Choice (as we have with abortion), we should have the good sense to recognize it for what it isn’t: enlightenment, civilization, progress, mercy. Nor is it an inalienable right. It is, rather, a shame, a sadness, a peril from which no congress’s legislation, no churchman’s dispensation, no public opinion or conventional wisdom can ever deliver us. For if we live in a world where birth is suspect, where the value of life is relative, and death is welcomed and well regarded we live in a world vastly more shameful, abundantly sadder, and ever more perilous than all the primitive generations of our species before us who were sufficiently civilized to fill with wonder at the birth of new life, dance with the living, and weep for the dead.

Is a suicide less a killing than a homicide? When the killer and the one killed are one and the same, does it mitigate the offense of killing?

The absence of outrage is an outrage itself.

Where abortion is available on demand, should we really expect to moderate or regulate assisted suicide?

Where choice is enshrined we must suffer the choices. Where life is sacred we must suffer life.

“The slippery-slope argument!” someone always says – as if to name it is to nullify it. As if things don’t go from bad to worse. As if gravity did not exist. Most of us just want to keep our balance”

But if we are not to be a burden to our children, then to whom? The government? The church? The taxpayers? Whom? Were they not a burden to us – our children? And didn’t the management of that burden make us feel alive and loved and helpful and capable?

In even the best of caskets, it never all fits – all that we’d like to bury in them: the hurt and forgiveness, the anger and pain, the praise and thanksgiving, the emptiness and exaltations, the untidy feelings when someone dies. So I conduct this business very carefully because, in the years since I’ve been here, when someone dies, they never call Jessica or the News Hound.They call me.

Quotes from The Undertaking by Thomas Lynch

“Si vous voulez voir la nature belle et vierge comme une fiancée, allez là par un jour de printemps ; si vous voulez calmer les plaies saignantes de votre cœur, revenez-y par les derniers jours de l'automne ; au printemps, l'amour y bat des ailes à plein ciel, en automne on y songe à ceux qui ne sont plus.”

Le Lys dans la vallée, Honoré de Balzac 1835

Post link