#gabriel garcia marquez

Our story sounds different every time my mother tells it.—Aglaja Veteranyi, Why the Child Is Cooking in the Polenta

My literary fathers tend to stick around. The late Gabriel Garcia Marquez lived a long, wild life, even if it ended in unjust and heartbreaking—yet poetic, inevitable—dementia. My literary mothers die untimely and tragic deaths.

Unless, of course, they’re Toni Morrison. But Toni is mother to us all; I can’t claim her for myself. She is the grand matriarch who refuses to lay down with every single word.

Yes, I have many mothers, but still I am waiting on my mother to come back for me. You—some of you few unlucky orphans—know this feeling. Having many literary mothers is a little like being raised by wolves. Having many mothers means you still nurse when the first mother looks away. Or when her body is scavenged by lesser animals, many of them inside of her.

My literary mother Angela Carter wrote her final novel after being diagnosed with cancer. Leaving behind a small son and husband, she still made a party of words. She wanted us to remember “What a joy it is to dance and sing!” In fact Wise Children—full of birthdays and babies and twins and magic and Shakespeare and Carnival—ends in incest between a seventy-five-year-old and her hundred-year-old uncle. What a way to go out, Angela. Mom, white-wine drunk again.

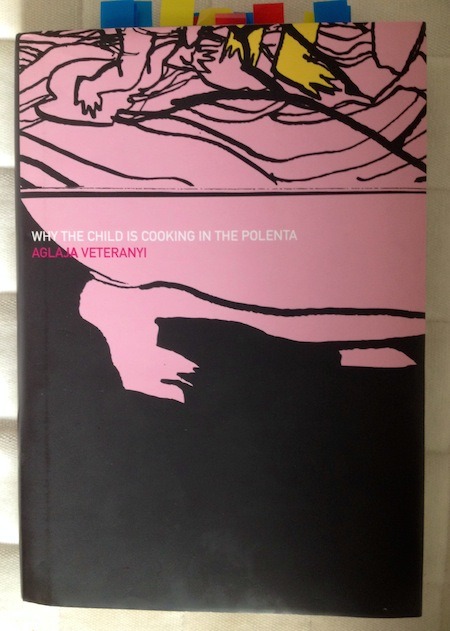

But I want to tell you today about my mother Aglaja Veteranyi, whom you probably never heard of, and who drowned herself in 2002 in Lake Zurich. A Swiss writer of Romanian origin, Veteranyi was part of a touring circus. Her stepfather was a clown and her mother an acrobat. She, herself, was made to juggle and dance. This is the subject of the novel Why the Child Is Cooking in the Polenta, which she published before she took her own life (other works were released posthumously).

My mother Aglaja is a child, herself. My mother is waiting for her own mother to return, because she has been abandoned at an orphanage. My mother Aglaja feels that “home is nowhere, betrayal is everywhere,” (195). She yearns for her mother’s polenta, which, in her native Romanian, mamaliga, translates roughly to “mother’s home cooking,” (197). Yet some part of her fighting for survival knows that to eat mamaliga is to eat poison. This, too, is how I know Aglaja is my mother.

The family was not Rom, but they were wanderers and outcasts, having fled poverty, austerity, and an illiterate Romanian dictator in 1967. The child narrator in Polenta feels dislocated because “Here [in this new place] everybody has warm water in their bathroom and a refrigerator in their heart,” (123). She understands that God is sad because he, too, is a foreigner. “Out of love for poor suffering humanity, God will eat polenta. He’s a foreigner himself, traveling from country to country. He’s sad because he has to start out on a long journey again,” (178).

WithPolenta, there is no dilution of Aglaja’s experience. Vincent Kling notes in his exquisite afterward, having had the vision to translate the work into English, that she is never detached. He explains that Aglaja’s voice offers the “adult retrospective viewpoint but at the same time the child’s passage through successive stages of awareness.” Every line is touching, funny, or pained. Everything is true. Always, she is with us.

I want to tell you about Aglaja Veteranyi because I read Polenta in a single sitting. I read this book looking up at Aglaja and thinking, how will I ever wear your clothes? I read this book thinking, Are you My Mother? I read this book thinking, You Can Be Nobody’s Mother. I read this and stopped every few sentences to write something. I read this believing that everybody should read this. I read this and felt afraid. I read this and thought of all those stories of the old witch who fattens children up to eat them. I read this and felt rage at not knowing the good-enough mother. I read this and thought how you can make a mother out of words. I read this and mourned because words are not always enough, not always. I read this and could not stop reading. I read this and knew what I wanted to be. I read this and knew where I came from. I read this and wanted to share my mother with you, so she could be your mother, too.

My father died of absence. My mother lives in helplessness. My sister is only my father’s daughter. I’ve grown up little by little. And I don’t want any children.—Aglaja Veteranyi

Recommended reading: Why the Child is Cooking in the Polenta, Aglaja Verteranyi, Dalkey Archive Press

EXTRA-SPECIAL JULY BONUS: Annie shares her smartypants annotations, saying “I am getting really intrigued by how people map texts (their own and others).”

We agree, and if you’ve any annotations or other visual media to share of your own literary mother (suggestions: altars to said idol, drawings, fan letters, collages, elaborate napkin notes, unsent sexts, autographs, marginalia, hair lockets, hair shirts, star maps, or assorted ephemera), send ‘em in, with or without an essay- we may add it as a regular feature!

Annie Liontas’ debut novel, LET ME EXPLAIN YOU, is forthcoming from Scribner in 2015. She is the recent recipient of a grant from the Barbara Deming Memorial Fund to conduct research in Trinidad for her newest work BADEYE, which also received Honorary Mention in the 2013 Dana Awards. Annie will be attending the 2014 Disquiet International Literary Program in Lisbon, Portugal on an Editor’s Choice Fellowship. Her story “Two Planes in Love” was selected as runner-up in BOMB Magazine’s 2013 Fiction Prize Contest and was published by BOMB in December. Other stories and poems have appeared in Ninth Letter,Night Train, and Lit. She graduated from Syracuse University’s MFA Program, where she was awarded the Creative Writing Department Fellowship and a 2013 Summer Fellowship. In 2003 and 2000 she received the Edna N. Herzberg Prize in Fiction at Rutgers University. Annie served as Editor-in-Chief of SALT HILL from 2012-2013. She co-hosts the TireFire Reading Series in Philly.

Es verdad!

Alcuni fumano, altri bevono, altri si drogano e altri si innamorano.

Ognuno si uccide a modo suo.

Cem Anos de Solidão - Gabriel Garcia Marquéz

Nunca soube responder quando me perguntam qual é o meu filme favorito ou a minha banda preferida, mas o mesmo não acontece com os livros. Quando por algum motivo se torna necessário eleger o livro da minha vida, tenho a resposta na ponta da língua: Cem Anos de Solidão, do Gabriel García Márquez.

A primeira coisa que acontece quando começamos a ler este livro é deixarmos de respirar. Desde a primeira frase, uma das mais célebres da história literária, [“Muitos anos depois, diante do pelotão de fuzilamento, o coronel Aureliano Buendía haveria de recordar aquela tarde remota em que o pai o levou a conhecer o gelo.”] que somos arrastados por um turbilhão de acontecimentos mágicos, sangrentos e escandalosos também, que giram em torno de uma família na qual os nomes se repetem geração após geração e com a qual viajamos para a frente e para trás no tempo, de forma tão fluída e tão rápida, que ficamos com o cérebro a doer ao tentarmos não perder o fio à meada. A segunda é que não conseguimos parar de ler, só mais um parágrafo, só mais uma página, só mais um capítulo, … Já estamos dentro do turbilhão!

Precisamente para não perder o fio à meada, sempre que leio este livro vou desenhando uma árvore genealógica, adicionando as personagens à medida que elas surgem no livro, ligando-as entre si pelas ligações familiares, amorosas e incestuosas (até ao nascimento do último Aureliano, que veio ao mundo com um rabo de porco, tal como avisava a lenda). Tenho a primeira árvore genealógica que desenhei da primeira vez que li o livro na sua última folha, mas nunca lá vou espreitar o resultado final, gosto de ir (re)descobrindo, aos poucos, a família e a sua história.

O livro Cem Anos de Solidão impressionou-me pela forma como descreve tão bem os desencontros e os escândalos das famílias (quem os não tem), o vazio da guerra sempre presente e a solidão enquanto única resposta possível perante certas crueldades da vida… E a forma como a vida anda sempre aos círculos, avós, pais, filhos, netos e tios, são iguais em nome e nas suas atitudes durante a vida. “…tudo o que neles estava escrito era irrepetível desde sempre e para sempre, porque as estirpes condenadas a cem anos de solidão não tinham uma segunda oportunidade sobre a Terra.” E não é a isso que estamos condenados todos, ao esquecimento, para sempre?

Aconselho a leitura de Cem Anos de Solidão não uma vez na vida, mas sim muitas vezes ao longo da vida! É um livro realmente especial, difícil de explicar por palavras. O melhor mesmo é lê-lo e deixar-se levar pela história.

Obrigada Mário pelo projeto Book Loving Girls! <3

Sónia Costa - 14 de Agosto de 2017

Post link

Con su terrible sentido práctico, ella no podía entender el negocio del coronel, que cambiaba los pescaditos por monedas de oro, y luego convertía las monedas de oro en pescaditos, y así sucesivamente, de modo que tenía que trabajar cada vez más a medida que más vendía, para satisfacer un círculo vicioso exasperante. En realidad, lo que le interesaba a él no era el negocio sino el trabajo. Le hacía falta tanta concentración para engarzar las escamas, incrustar minúsculos rubíes en los ojos, laminar agallas y montar timones, que no le quedaba un solo vacío para llenarlo con la desilusión de la guerra. Tan absorbente era la atención que le exigía el preciosismo de su artesanía, que en poco tiempo envejeció más que en todos los años de guerra, y la posición le torció la espina dorsal y la milimetría le desgastó la vista, pero la concentración implacable lo premió con la paz del espíritu.

Gabriel García Márquez,100 años de soledad.

“Distance isn’t the problem. We humans are the problem, that don’t know how to love without touching, without seeing or without hearing. Love is felt with the heart, not the body.”

Gabriel Garcia Márquez

Con el tiempo todo pasa. He visto, con algo de pasciencia, a lo inolvidable volverse olvido, y a lo impredecible sobrar.

Dark Letters

“Que te rompan el corazón está bien, al final a todos nos gusta armar rompecabezas… pero que se lleve las piezas, eso sí es jodido”.

Charles Bukowski.

Ahora estoy de regreso.

Llevé lo que la ola, para romperse, lleva

—sal, espuma y estruendo—,

y toqué con mis manos una

criatura viva;

el silencio.

Heme aquí suspirando

como el que ama y

se acuerda y está lejos.

“Nostalgia”, Rosario Castellanos

“Si en nombre del amor debo restringir mi libertad de expresión, bloquear mis pensamientos y sentimientos legítimos o decir lo que no pienso para no afectar el equilibrio de la relación o para no crear "malestar” en el otro, mi vínculo estará regido por el sometimiento y la prohibición. No busques encadenarte a un corazón, prefiere volar con quien elijas hacia un horizonte común".

Walter Riso

Es posible que, como apuntó Virginia Woolf en un cuento, el lenguaje no sea más que una frágil y agujereada red por la que se escapa, furtivo, el sentido. Por eso el silencio es tan poderoso: nos rodeamos de quien sabe interpretar nuestros silencios y adivina en ellos su sentido…

Eclipse solar de 1991 en Chiapas, por Antonio Turok.

“Se puede amar perfectamente sin que ame el otro. Es una cuestión de soledad. Por ese motivo es que en el amor siempre sobran las demandas de uno hacia el otro. Este es su gran defecto, pedirle siempre algo al otro, mientras que el estado de pasión entre dos o tres personas permite una comunicación intensa”.

Michel Foucault

Gabriel García Márquez, Love in the Time of Cholera (1985)

translated Edith Grossman (1988)

Fermina Daza was horrified when she heard the boat’s horn with her good ear, but by the second day of anisette she could hear better with both of them. She discovered that roses were more fragrant than before, that the birds sang at dawn much better than before, and that God had created a manatee and placed it on the bank at Tamalameque just so it could awaken her. The Captain heard it, had the boat change course, and at last they saw the enormous matron nursing the baby that she held in her arms. Neither Florentino nor Fermina was aware of how well they understood each other: she helped him to take his enemas, she got up before he did to brush the false teeth he kept in a glass while he slept, and she solved the problem of her misplaced spectacles, for she could use his for reading and mending. When she awoke one morning, she saw him sewing a button on his shirt in the darkness, and she hurried to do it for him before he could say the ritual phrase about needing two wives. On the other hand, the only thing she needed from him was that he cup a pain in her back.

Florentino Ariza, for his part, began to revive old memories with a violin borrowed from the orchestra, and in half a day he could play the waltz of “The Crowned Goddess” for her, and he played it for hours until they forced him to stop. One night, for the first time in her life, Fermina Daza suddenly awoke choking on tears of sorrow, not of rage, at the memory of the old couple in the boat beaten to death by the boatman. On the other hand, the incessant rain did not affect her, and she thought too late that perhaps Paris was not as gloomy as it had seemed, that Santa Fe did not have so many funerals passing along the streets. The dream of other voyages with Florentino Ariza appeared on the horizon: mad voyages, free of trunks, free of social commitments: voyages of love.

…Contrary to what the Captain and Zenaida supposed, they no longer felt like newlyweds, and even less like belated lovers. It was as if they had leapt over the arduous calvary of conjugal life and gone straight to the heart of love. They were together in silence like an old married couple wary of life, beyond the pitfalls of passion, beyond the brutal mockery of hope and the phantoms of disillusion: beyond love. For they had lived together long enough to know that love was always love, anytime and anyplace, but it was more solid the closer it came to death.

…The Captain looked at Fermina Daza and saw on her eyelashes the first glimmer of wintry frost. Then he looked at Florentino Ariza, his invincible power, his intrepid love, and he was overwhelmed by the belated suspicion that it is life, more than death, that has no limits.

Post link

It has been one long hiatus, a lot of things happening in life took over my attention. I don’t think I need to explain myself, it is 2020 after all. But now that I am back and have new books on my shelves again that I cannot wait to devour one by one.

When this collection first reached home I was visibly suprised to notice that they were all fiction. Some weeks ago I had written this really long entry into my journal where I talked about how it was almost getting nerve wrecking for me to pick a good, fresh fiction novel again because of how choosy I had become over the years. I had transitioned to non-fiction a long time ago as I thought everyone does eventually and also, it suited my academic needs very well back then. And ever since then, other than a few short stories here and there, or some really mad popular novels that I am recommended more than a dozen times, I had hardly gone beyond the non-fiction genre. Coming back home during this pandemic I found myself in front of a stack of all fiction novellas from my preferences 6 years ago. I am embarassed to say that I immediately looked down upon them and proceeded to read a few memoirs and academic papers on my laptop instead. The fact that I ended with this stack right here shows how I did not stick to the heavy stuff like I planned to either.

I am learning about my own reading habits, with a lot of introspection involved. I am consciously trying to change a few things that I find problematic right now even if they weren’t a few years back. It is a process, and all I need is some patience and more books around me.

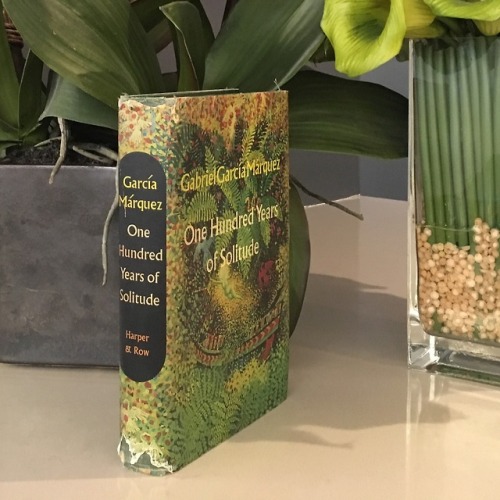

2017 favorite books

- A hundred years of solitude by Gabriel García Márquez

- Samarkand by Amin Maalouf

- Suddenly Last Summer by Tennessee Williams

- The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro

- Ken a Short Story by Yukio Mishima

- The Sellout by Paul Beatty

C’est fini !…Reste la nostalgie de le refermer…

C’était un vieux livre retrouvé dans ma bibliothèque, sans jaquette, qui s’est tout disloqué au cours de ma lecture comme les parchemins de Melquiades…

Certaines images ne peuvent s’oublier !…Les papillons jaune, les fourmis rouges, les médecins invisibles, les gamines qui faisaient l’amour pour manger, la petite fille qui mangeait de la terre, les ricochets de lumière et même les betteraves nocturnes des sources de Lérida…

“ Nul ne savait plus où commençait et où finissait la réalité”…

Post link

Úrsula on the other hand, held a bad memory of that visit, for she had entered the room just as Melquíades had carelessly broken a flask of bichloride of mercury.

“It’s the smell of the devil,” she said.

“Not at all,” Melquíades corrected her. “It has been proven that the devil has sulphuric properties and this is just a little corrosive sublimate.”

Gabriel García Márquez: One Hundred Years of Solitude

Gastón Betelli: Melquíades en sus postrimerías

Post link