#nuclear war

Dora, children at school tend not to have nuclear weapons

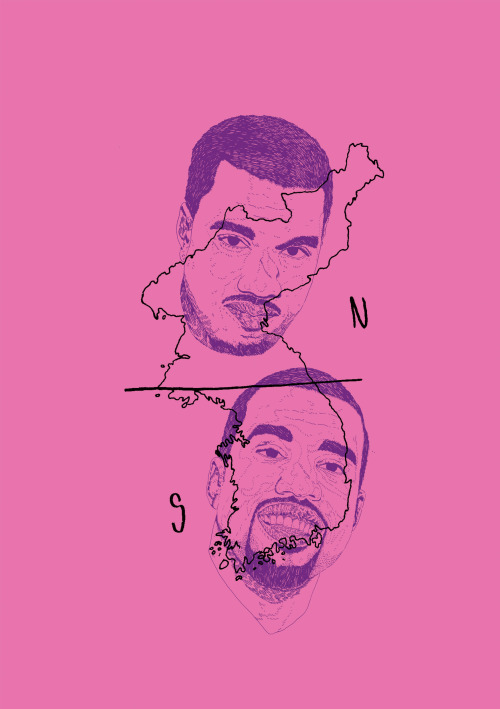

KUDZURU.NUCLEAR WAR

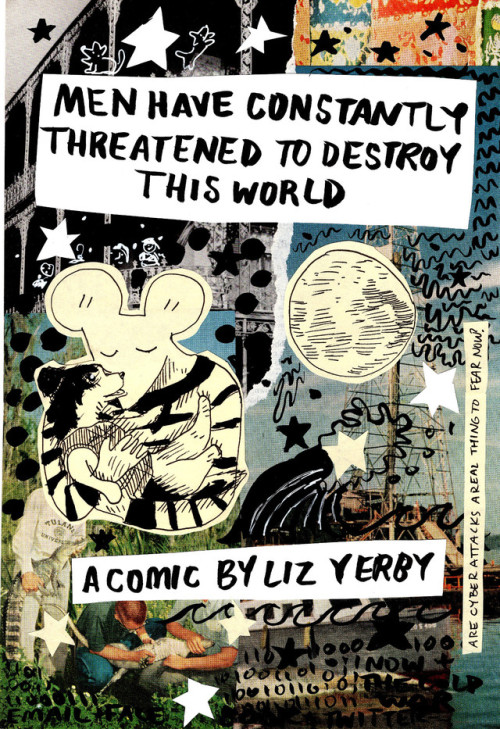

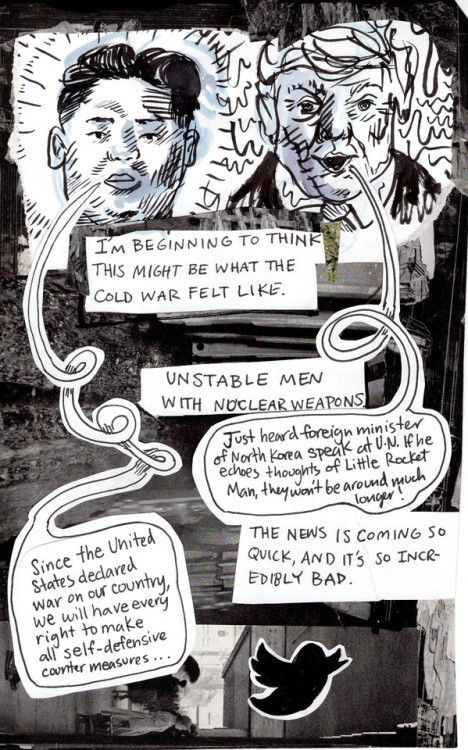

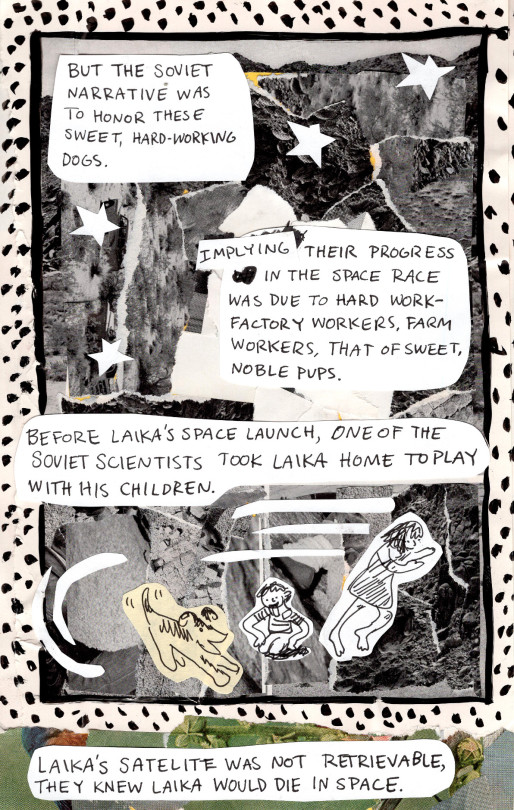

Chapter Covers

This project was drawn in 2020. There is story about little country, that was going through nuclear attack during one week. Now the events described in the pictures are felt more painful. Let there be peace.

Monday Morning Links!

* Paradoxa 32 has a cover.

* Boys don’t read enough.

* The era of high fertility is ending. Every child on their own trampoline. Police-Free Childhoods. The Seismic Generational Shift in Worldview: Millennials Seek a Nation Without God, Bible and Churches.

* Selfies, Surgeries And Self-Loathing: Inside The Facetune Epidemic.

* The Bullshit Jobs Boom.

* The empty brain. Your brain does not…

A Proposed Solution to the Ukraine War:

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine began, what was a regional conflict has become a global hybrid war with ever-greater stakes, not least the risk of nuclear war.

Perhaps the greatest danger lies in the difference of motives between parties, which is also the fundamental cause of this war: Russia seeks security, while the U.S. and its NATO allies have been using Ukraine to deny that security — to “break Russia,” in Henry Kissinger’s 2015 phrase. The U.S. does not want peace, unless it be the peace of a conquered Russia. That is why there is no obvious end to the escalations and counter-escalations. The U.S. and NATO see opportunity in the war they have been trying so hard to provoke.

The tragedy is that few people seem to understand that at the root of the Ukraine crisis is a specific strategy known as the Wolfowitz Doctrine, named after Paul Wolfowitz who, as under secretary of defense in the administration of George H. W. Bush, was one of the authors of a 1992 document that laid out a neo-conservative manifesto aimed at ensuring American dominance of world affairs following the collapse of the Soviet Union. -Writer: Greg Mello (Los Alamos Study Group)

What is the Los Alamos Study Group?

“One of the most respected and best informed anti-nuclear war groups in the world is the Los Alamos Study Group. Founded at the end of the Cold War in Los Alamos, New Mexico, where the first nuclear bombs were designed and built, the LASG’s aim of taking nuclear weapons out of foreign policy. It has won landmark environmental, civil rights and freedom of information lawsuits in the U.S., provided hundreds of top-level briefings, and played a crucial role in preventing the production of the core elements of plutonium warheads. As nuclear war threatens over Ukraine, the LASG has released this remarkable and urgent analysis of the risks and the solutions. "— John Pilger.

I fear we’ve never been closer to going nuclear says DOMINIC SANDBROOK

“Today, thanks to the escalating bloodshed in Ukraine, the planet is probably closer to nuclear conflict than at any time since the darkest days of the Cold War.

And it may not be an exaggeration to say that our future depends on a single, volatile, unpredictable and — if the rumours are to believed — increasingly sick man.

Since the first days of his attack on Ukraine, Vladimir Putin has repeatedly raised the spectre of nuclear war. He began his campaign by putting Russia’s nuclear forces on ‘special alert’ against Western intervention, and in recent days his rhetoric has reached ever more paranoid heights.

Last Wednesday, after the test of the massive new Sarmat nuclear missile, which can carry 15 warheads and reportedly wipe out an area the size of Britain, he told Russian politicians that he would be 'lightning-fast’ to use it if the West dared to meddle in Ukraine.

Other signs are equally worrying. In recent days there has been a marked change in the Kremlin’s rhetoric, casting its operation as an existential struggle against Nato and the West rather than a 'special operation’ against Ukrainian nationalists.

Russian state television, too, has become positively hysterical. Putin’s chief propagandist, Vladimir Solovyov, told millions of viewers this week that 'one Sarmat means minus one Great Britain’.

And in a truly deranged segment on Sunday evening, Channel One anchor Dmitry Kiselyov said on his prime-time news show that Moscow could wipe out Britain with a nuclear tsunami in a strike by Russia’s Poseidon underwater drone: 'Having passed over the British Isles, it will turn whatever might be left of them into a radioactive wasteland.’

Can they be serious? Are these war-crazed puppets genuinely preparing public opinion for a Russian nuclear strike? Or is this merely empty bluster, a desperate attempt to intimidate the West as Russia’s tanks stall in the spring mud? The chilling answer is that nobody really knows.

And while a surprise nuclear attack on Britain — or any major Western country — strikes me as very unlikely, many military analysts believe the Russians could be closer to breaking the nuclear taboo than at any time since the 1940s.

(…)

As early as 1954, when nuclear weapons were infinitely less destructive than they are today, the Ministry of Defence estimated that a single hydrogen bomb dropped on London would probably kill four million people.

A full-scale Soviet attack on Britain would kill nine million people straight away, and a further three million from short-term fallout. Four million more would be severely injured or disabled.

As the technology improved, the potential death toll rose. By 1983, a study by the British Medical Association suggested that a nuclear attack on Britain would kill about 33 million people. And they would be the lucky ones, since the survivors would be left to die slowly of starvation or radiation sickness in a post-apocalyptic wasteland.

(…)

So when you read the National Archives’ declassified accounts of government war games from the early 1980s, it’s striking that they often end with the Red Army surging towards the Rhine and the British Cabinet authorising a strike on a communist satellite such as Poland or Bulgaria, in order to bring the Kremlin to the negotiating table.

That tells you something. Nuclear weapons are weapons of weakness.

The price for using them is so high — not least in risking massive retaliation and the potential destruction of your own civilisation — that no vaguely sane leader would consider it unless his country was facing utter disaster.

And that, of course, brings us to Vladimir Putin. For this is precisely where he finds himself.

Two months ago, he staked his personal credibility, the future of his regime and Russia’s place in the world on the success of his Ukrainian invasion, a gamble he may well be losing.

(…)

And once the taboo was broken, where would you stop? If Putin used more nuclear weapons, would U.S. President Joe Biden issue an ultimatum? Would he authorise a strike against Russia?

And if so, where would it end? With the stakes so high, how could such a war be contained?

(…)

The other possibility, which is even more frightening, is that an angry, ailing Putin might lash out against Nato itself. In recent days he and his puppets have issued furious denunciations against countries backing Ukraine.

So what if, staring defeat in the face, he authorised a strike against a military base in the Baltic, or a Polish transport depot handling supplies to Kyiv?

Would the West cave in and impose a negotiated peace? Would our leaders do nothing? Or would they feel the need to retaliate, as our Eastern European allies would surely demand?

The truth, I suspect, is that even a 'limited’ battlefield strike might set the world on a path towards total catastrophe, leaving hundreds of millions dead and the planet ravaged beyond recovery.

'I do not think there is any such thing as a tactical nuclear weapon,’ the former U.S. Defense Secretary, General James Mattis, remarked four years ago.

'Any nuclear weapon used any time is a strategic game-changer.’

Dreadful as it may be to admit it, Mattis is right. If Vladimir Putin were to approve a nuclear strike — however limited in theory — that moment could easily be the beginning of the end.

Few of us in the West would countenance appeasement, but that might leave escalation as the only alternative.

Who knows how Joe Biden would react? And who among us can confidently say how we would react in such a terrible scenario?

(…)

But it strikes me that ever since that first test in the New Mexico desert, mankind has been enormously, and perhaps undeservedly, lucky. As a species, we have been arrogant and reckless enough to build weapons that can destroy us many times over.

We have survived several near-misses, and every time we have congratulated ourselves on our good sense. And we have forgotten that it takes only one vicious, bitter, unpredictable man to set the world on a path to utter destruction.

I repeat: it may not happen. So far, to his credit, Mr Biden has handled the Ukrainian crisis with an admirable combination of firmness and restraint.

And even somebody as drunk on his own nationalist resentments as Vladimir Putin must realise that a nuclear war would mean the end of Russian civilisation — the end of Moscow, St Petersburg and everything he and his cronies claim to revere.

Yet, like all those people who lay awake during the Cuban Missile Crisis, wondering if they would ever see tomorrow, I can’t banish a sense of dread.

And I can’t help thinking of J. Robert Oppenheimer that morning in the New Mexico desert, and those words from the Hindu scriptures: 'I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds …”

Opinion | Putin Really May Break the Nuclear Taboo in Ukraine

“Why would Vladimir Putin use tactical nuclear weapons? Why would he make such a madman move?

To change the story. To shock and destabilize his adversaries. To scare the people of North Atlantic Treaty Organization countries so they’ll force their leaders to back away. To remind the world—and Russians—that he does have military power. To avoid a massive and public military defeat. To win.

Mr. Putin talks about nuclear weapons a lot. He did it again Wednesday: In a meeting with politicians in St. Petersburg, he said if anyone intervenes in Ukraine and “creates unacceptable threats for us that are strategic in nature,” the Russian response will be “lightning fast.” He said: “We have all the tools for this that no one else can boast of having. We won’t boast about it, we’ll use them, if needed.”

He’s talked like this since the invasion. It’s a tactic: He’s trying to scare everybody. That doesn’t mean the threat is empty.

There are signs the Russians are deliberately creating a historical paper trail, as if to say they warned us. On Monday Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said the risk of nuclear conflict is “serious” and “should not be underestimated.” Earlier, Anatoly Antonov, Russia’s ambassador to Washington, sent a formal diplomatic note to the U.S. saying it was inflaming the conflict. The Washington Post got a copy. It said shipments of the “most sensitive” weapons systems to Ukraine were “adding fuel” to the conflict and could bring “unpredictable consequences.”

(…)

So let me make an argument for my anxieties: For this man, Russia can’t lose to the West. Ukraine isn’t the Mideast, a side show; it is the main event. I read him as someone who will do anything not to lose.

In October he will turn 70, and whatever his physical and mental health his life is in its fourth act. I am dubious that he will accept the idea that the signal fact of its end will be his defeat by the West. He can’t, his psychology will not allow it.

It seems to me he has become more careless, operating with a different historical consciousness. He launched a world-historic military invasion that, whatever his geostrategic aims, was shambolic—fully aggressive and confident, yet not realistically thought through. His army wasn’t up to the task. It seemed thrown together, almost haphazard, certainly not professional.

Richard Haass, president of the Council on Foreign Relations, often notes that Mr. Putin has killed all the institutions in his country, sucked the strength, independence and respectability from them, as dictators do. They take out power centers that might threaten them but might also warn them of weaknesses in their own governments. All dictatorships are ultimately self-weakening in that way. But this means Mr. Putin has no collective leadership in Russia. It’s all him. And he’s Vladimir Putin.

When I look at him I see a new nihilistic edge, not the calculating and somewhat reptilian person of the past.

(…)

No one since 1945, in spite of all the wars, has used nuclear weapons. We are in the habit, no matter what we acknowledge as a hypothetical possibility, of thinking: It still won’t happen, history will proceed as it has in the past.

But maybe not. History is full of swerves, of impossibilities that become inevitabilities.

(…)

Think more, talk less. And when you think, think dark.”

“War can be said to become ‘total’ in at least two main senses: on the one hand, in the sense most used by social scientists, that it more and more completely incorporates the whole of social life; and on the other, in the military (Clausewitzian) sense, that it increasingly becomes an ‘absolute’ struggle of life and death for states and peoples. In reality, these are but two sides of the same process. The political-economic totalisation of war both facilitates and requires the military-technological totalisation. This is why the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, which obliterated a city and threatened an era of war as total annihilation, represents a logical conclusion to a century of industrialised warfare.” (page 38)

“A great deal has been written about the links between the post-war arms race and the economy. On the one hand, it has been suggested that the alliance of the military and the industrial sectors dependent on them constitutes a military industrial complex, which dominates and directs American society in particular. C. Wright Mills’s 1956 study of The Power Elite gave great weight to military-industrial linkages within a system of power which as a whole had increasingly been centralised by military conflict and nuclear technology. Thompson argues, even more radically, that modern societies ‘do not have military-industrial complexes - they are military-industrial complexes’. For him, ‘exterminism’ is the driving force of the entire social system. On the other hand, more specifically economic analyses were put forward to suggest that Western (and, by implication, Eastern) systems were ‘arms economies’ in which arms production provided the central dynamic of the economic system as a whole. Originally developed during the Second World War and its immediate aftermath, especially Korea, as a theory of a Permanent War Economy, this was subsequently modified as it was recognised that nuclear weapons could inhibit major wars while stimulating military expenditure which had a fundamental economic effect. So the arms economy was presented as an explanation of the post-war boom.” (page 41)

“Total war becomes less total in the sense of direct social participation at the very point at which it becomes greatly more total, indeed potentially absolute, in the military sense. Thus while in one sense it is utterly correct to see the entire global social system as conditioned by total war - in exterminist terms - much of social reality apparently contradicts this insight. The economic, social, even political and ideological links between the arms race and most social life become less direct, the more sophisticated and lethally accurate nuclear weaponry becomes. The nuclear arms race has largely been conducted out of sight of society, with states deliberately eschewing even ideological, let alone practical, mobilisation. Even in the United States, by far the most obviously militarist of Western societies, militarism and related political and nationalist ideologies are far less unequivocally dominant than they were in the ‘Cold War’ of the first decade after 1945. This has a great deal to do with the fact that the function of actual war has radically altered. War cannot be recognised unequivocally even as a possible outcome of war preparation; and war, if it came, would not heighten social mobilisation as in all previous phases, but result in the most extreme demobilisation - physical destruction of the majority of society’s members.” (pages 44, 45)

“The reasons for the development of radical politics in the first two phases of total war were mainly to do with the contradictions of military participation. Both the First and Second World Wars involved total societal mobilisation. A nuclear war, however, will mobilise society as a whole only in the sense of Auschwitz, by delivering it to mass destruction. The mobilisation process proper is transferred back into the war-preparation stage: but, as we have seen, nuclear militarism is not mass militarism in the same sense. Small professional armed forces and technologically skilled work forces in the armaments industries ‘participate’ more or less directly; the mass of society participate mainly in the sense of ideological mobilisation. Even this ideological mobilisation, as an active process, is limited to periods of relative crisis in international relations and the arms race.” (page 103)

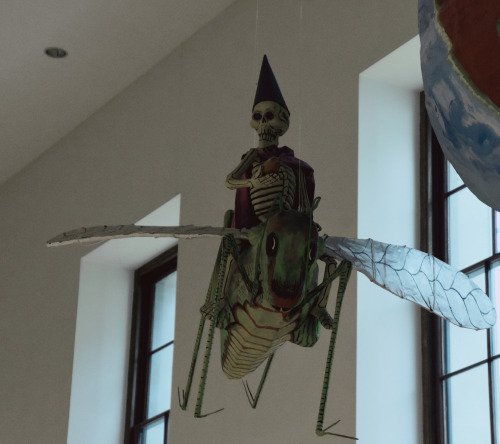

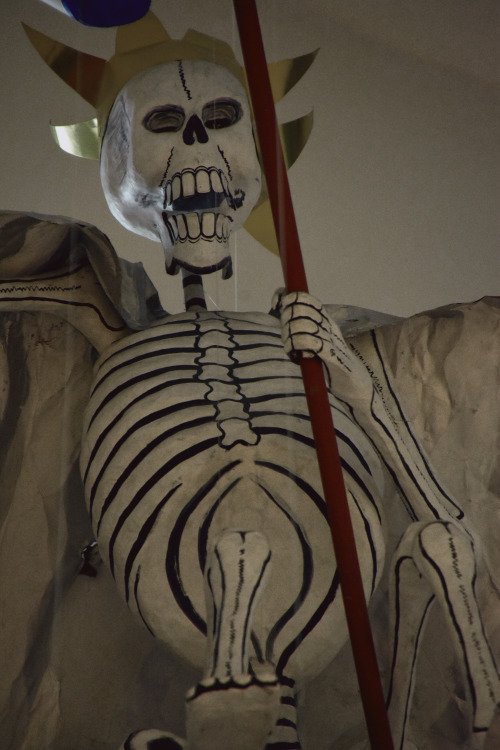

Models of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (Mexico 1980 Linares Family) fly high at the British Museum- London England

Post link

when Skynet launches the missiles AI risk deniers will really be like, “well that’s impressive, but it doesn’t have an internal conscious experience or qualia, it’s just executing an algorithm”

Even a very simple Dead Hand-style system could cause an unintended nuclear launch in the right combination of circumstances, but conceiving of that as “AI risk” that should be addressed by solving an “AI alignment problem” seems unlikely to lead to an effective solution.

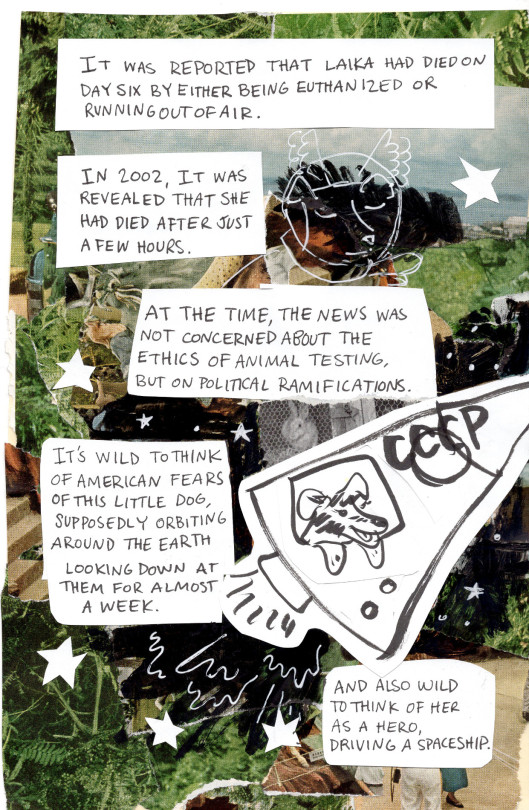

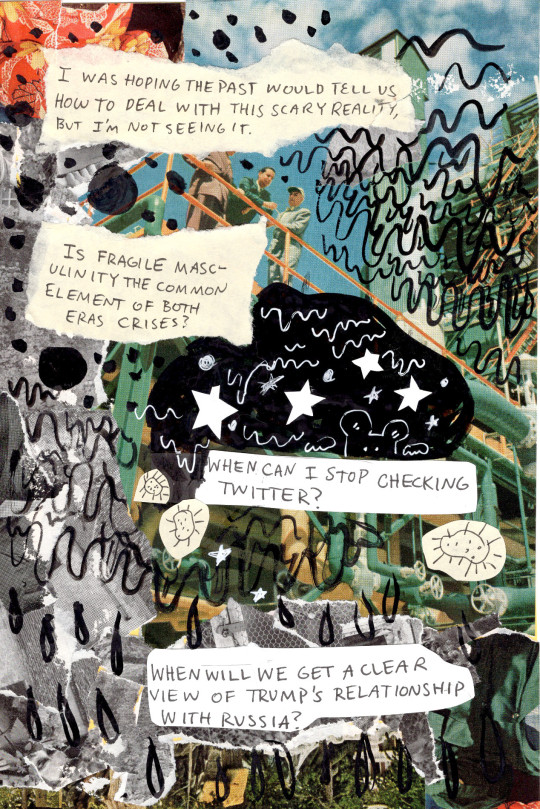

Paranoia Girls: Page Twenty-Four

(Dedicated 2 Prince)

Pictures: Yunico Uchiyama

Words: Patrick Macias

Translation / Coordination: Marie Iida

May u live 2 see the dawn

Post link