#corinthian

THE SANDMAN UNIVERSE: NIGHTMARE COUNTRY #5

Written by JAMES TYNION IV

Art by LISANDRO ESTHERREN and AARON CAMPBELL

Cover by REIKO MURAKAMI

Variant cover by AARON CAMPBELL

1:25 variant cover by SAM WOLFE CONNELLY

$3.99 US | 32 pages | Variant $4.99 US (card stock)

ON SALE 8/9/22

When Madison Flynn first crossed paths with the Corinthian, and saw his true nature, she reacted with astonishment and wonder, not fear. Across all his lifetimes, she was one of the only living things to ever see him that way. And now she will learn what a terrible mistake that was.

Khirbet edh-Dharih

Jordan

100 CE

22x16 m

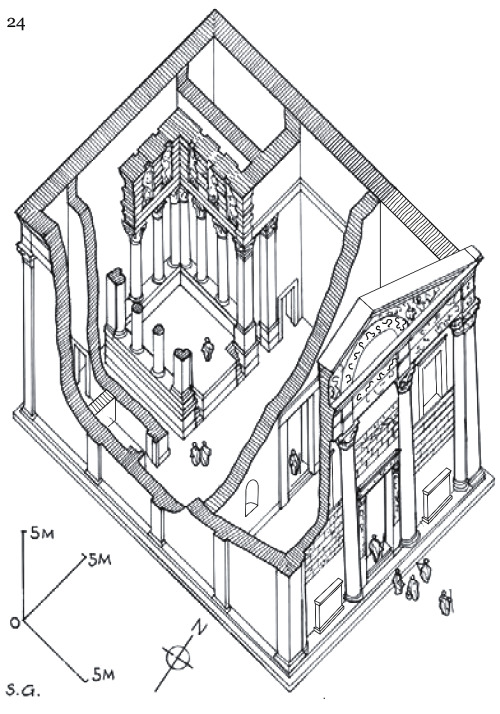

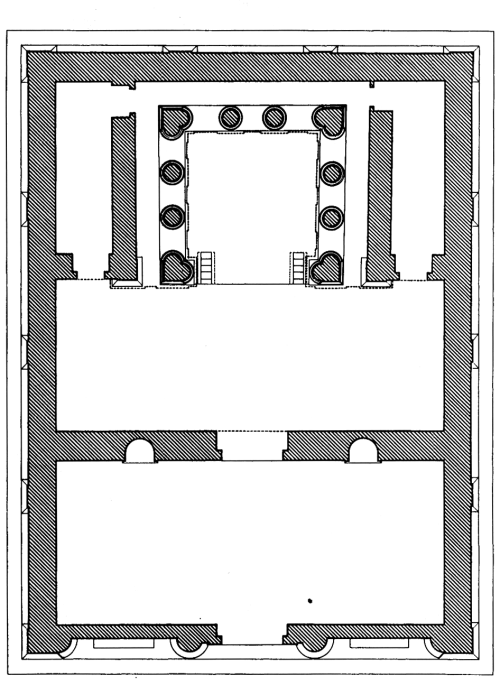

Dharih’s Nabataean settlement can be roughly dated to around 100 CE. It flourished during a period of prosperity in times of the Roman annexation of the Nabataean Kingdom.

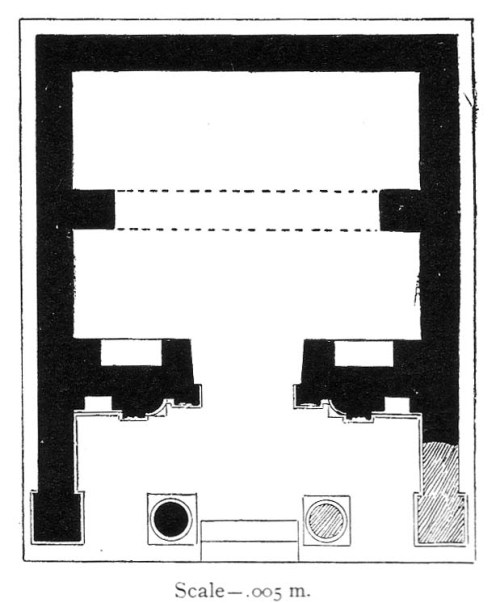

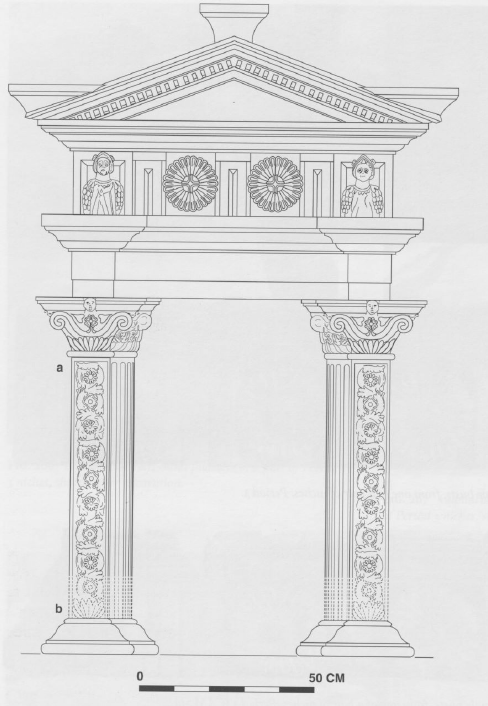

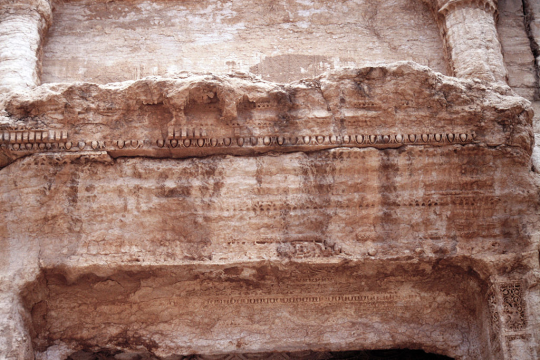

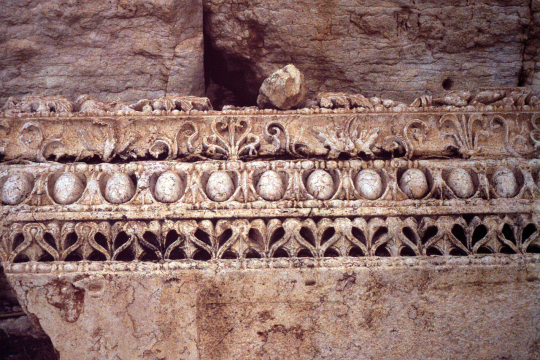

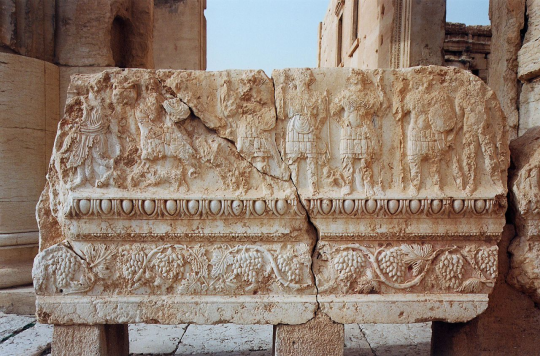

The temple (22 m x 16 m) consists of an unroofed vestibule to the south which opens to an almost square complex to the north, with a cultic platform in its center. The façade facing south was 15 meters high. It had two protruding pedestals that used to host statues on each side of the entrance door, and two large windows above them. The architrave was decorated with carved vines and animals, and had Medusa heads at the corners. The frieze above displayed figures of the Zodiac alternating with winged Victories, and the triangular pediment, sea centaurs crowned by flying Victories. Standing eagles guarded the central figures. While several of the mentioned figures can be seen at the Jordan Museum, the central couple of gods, Dushara and al-‘Uzza, can only be guessed from fragments.

The columned podium (7 x 7 m, height 1.40 m) in the center is accessed through two narrow stairways in the front. In the central slab of its pavement is a rectangular hole flanked by two small circular ones. Beneath the slab, a stone basin was found. The excavators interpret this as a system for sticking a betyl, and collecting the offering liquid after the ritual libations. It is not clear if this would have been wine, oil, or even blood. In a later phase, further two betyl holes were added in diagonal, which indicates a cult of a triad of gods.

A narrow U-shaped corridor surrounds the podium on three sides to circumambulate it in ritual processions. The hallway also gives access to two crypts situated under the platform and to the corner rooms. The northeast one encloses a staircase that used to lead to a terraced roof, and the two on the northwest side have large wall cupboards.

It is assumed that the craftsmen of the Dharih temple were the same who decorated the temple on the peak of Jabal et-Tannur.

Post link

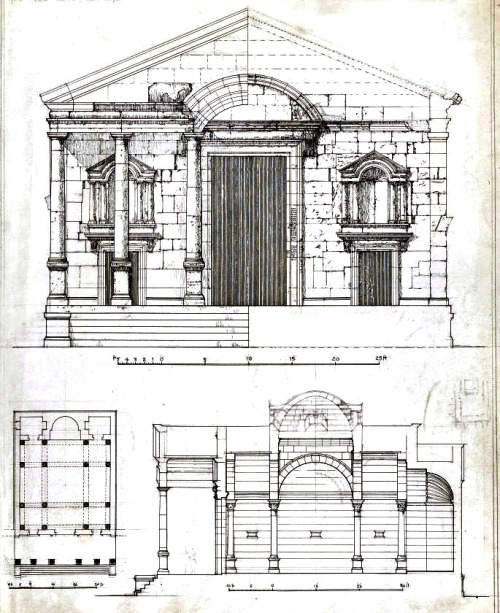

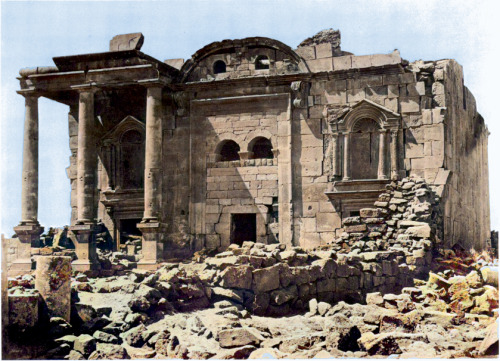

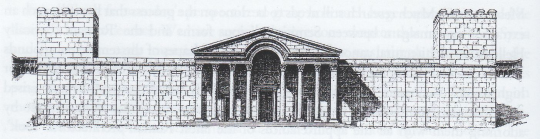

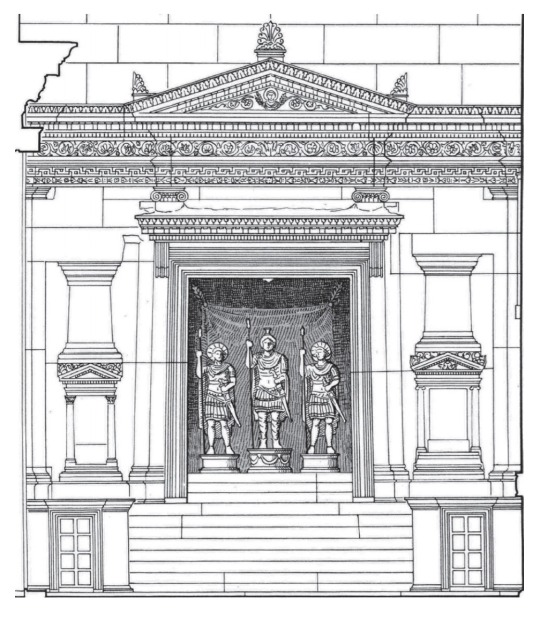

“The Praetorium”

Phaena (Al-Masmiyah), Trachon, Syria

160–169 CE

24.8 x 16.4 m

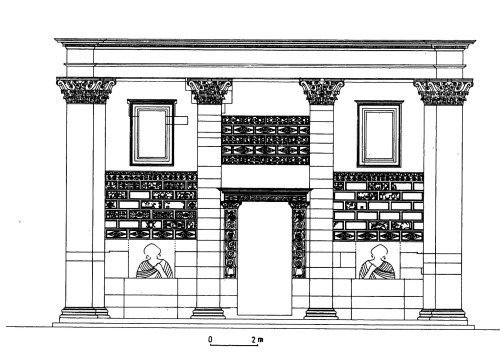

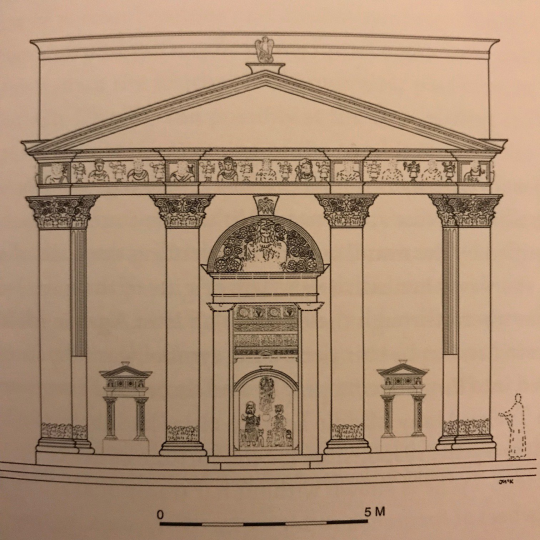

Along with the Roman temple dedicated to Tyche in nearby al-Sanamayn, the Praetorium of al-Masmiyah is the only Roman temple in the Levant that contains niches for statues in the cella. This unique feature in Roman architecture was likely inspired by pre-Roman architecture, particularly the temple of Baal-Shamin in the Syrian Desert town of Palmyra or in various Arabian cities.

The Praetorium was situated atop a podium in a temenos surrounded by colonnades and was constructed by the commander of the Third Gallic Legion between 160–169 CE during the reign of the Roman emperors Aurelius Antoninus and Lucius Aurelius Verus. It was relatively small, measuring 24.8 x 16.4 meters. It has a rectangular ground plan with a semi-circular apse that projects onto one side of the building opposite of the doorway. Both sides of the doorway contained niches reserved for statues. The interior space consisted of a single room, which was the naos, and measured 15.09 x 13.78 meters.

The Praetorium was formerly topped by a square domed roof, likely a cloister vault, which had since collapsed. The roof is supported by four free-standing columns fixed at the inner angles of cross-vaulted arches, which together form a Greek cross. On the opposite end of each columns stood a half-column, making for a total of four main columns, eight half-columns, and four quarter columns (situated at each corner) inside the naos. The arches sit on lintels that span the space between the outer wall and the columns supporting the roof. There were six niches against the walls that were reserved for the placement of statues and in the center of them was the main space, the adyton, used to hold the main statue of the pagan cult. The adyton was topped by a conch-shaped half-dome. The building had two windows, a rare feature in Classical pagan temples, and a total of three entryways. Of the entry ways, there was a principal central doorway that was higher and broader than the two side-doors.

that was constructed by the commander of the Third Gallic Legion between 160–169 CE during the reign of the Roman emperors Aurelius Antoninus and Lucius Aurelius Verus.

Sources:1

Post link

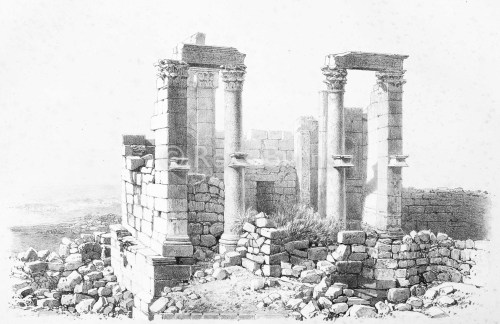

Temple C (Kalybe of Kanatha)

Kanatha (Qanawat), Hauran, Syria

2-3rd century CE

The Temple was a square structure, whose entrance façade, was made of of a four-pillar propylon, nestled between corner pillars facing north. This array, resembling the distyle in antis is quite rare in classical architecture. The four column had corbels designed for placing statues at about half their height. This decorative element is also quite rare in classical architecture, and is found only in a few sites in Syria. The space between the two main pillars in is greater than the spaces between the side pillars and it carried a Syrian gable, with its curve towards an arch is still visible.

The two long east and west walls of the temple were smooth. They stand behind the pilasters of the propylon and connect to the south wall of the temple, i.e. to a wall in the center of which is the apse. The southern wall, that is, the wall in front of the entrance, was designed as having a semicircular apse with adjacent rectangular rooms on both sides. Both rooms opened to the north, that is, towards the inner space of the temple.

Inside the rounded wall of the apse were three ornate niches, rounded in the outline, which were arranged symmetrically: a niche with a larger opening in the center and next to it smaller niches. The inner space of the temple, which is located between the apse wall and the propylon at the entrance, and between the two long walls wasn’t roofed. Entering the temple through the Syrian gable- crowned propylon, one would find himself standing in a rectangular plaza that stretched in front of the two-story wall with a semi-circular niche in the center, covered by a half-dome in which the emperor’s statue stood.

A Kalybe (κάλὑβη) is a type of temple found in the Roman East dating from the first century and after. They were intended to serve as a public facade or stage-setting, solely for the display of statuary.They were essentially stage-sets for ritual enacted in front of them. The kalybe has been associated with the Imperial Cult.

below: remains of geometric wall painting on western conch of adyton

Post link

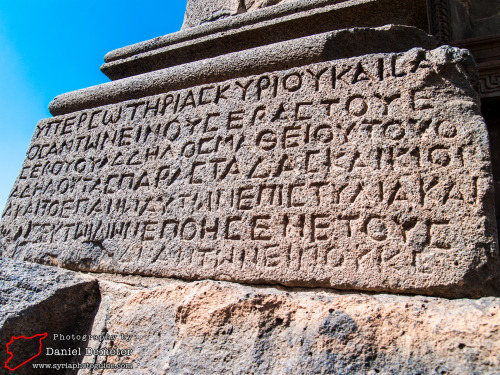

South Temple of Atil

Atil, Hauran, Syria

151 CE

This small town contains two almost identically designed Roman temples, delicately fashioned from the local basalt stone. The south Temple stems from the Antonine period (151 CE) the second or North Temple (probably dedicated to the Nabataean deity, Theandrites) was built in 211–212 CE.

The southern temple is better preserved, while the northern temple has been incorporated into a modern house and tomb. Both have attractively decorated facades with fine detail.

Closeup of the Greek inscription at Atil, Syria. The inscription dates the construction of the temple to the 14th year of the reign of Antoninius Pius (151 CE).

Post link

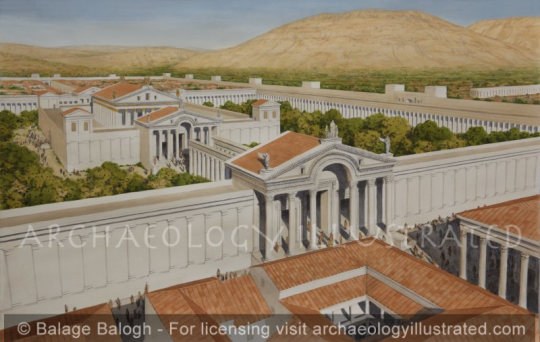

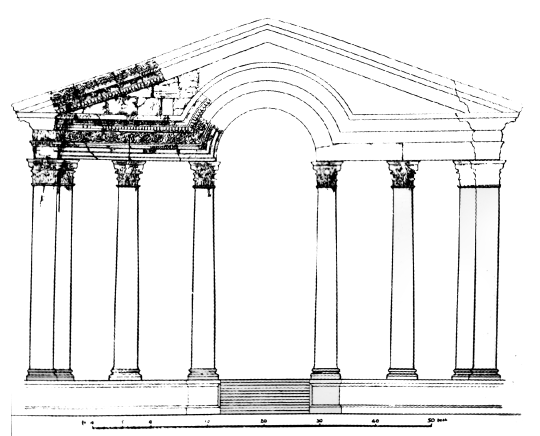

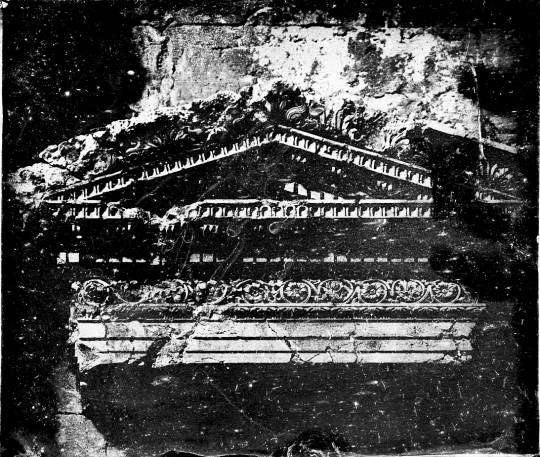

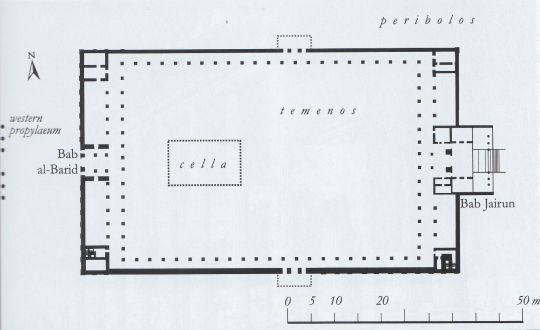

Temple of Jupiter

Damscus, Syria

1st century BCE - 3

Damascus was the capital of the Aramaean state Aram-Damascus during the Iron Age. The Arameans of western Syria followed the cult of Hadad-Ramman, the god of thunderstorms and rain, and erected a temple dedicated to him at the site of the present-day Umayyad Mosque. It is not known exactly how the temple looked, but it is believed to have followed the traditional Semitic-Canaanite architectural form, resembling the Temple of Jerusalem. The site likely consisted of a walled courtyard, a small chamber for worship, and a tower-like structure typically symbolizing the “high place” of storm gods, in this case Hadad.

The Temple of Hadad-Ramman continued to serve a central role in the city, and when the Romans conquered Damascus in 64 BCE. The Romans believed that each site (mountain, river, wood, etc.) had its own deities (genius loci); this approach led them to accept the beliefs of the countries they conquered; in the case they assimilated Hadad with their own god of thunder, Jupiter, and Hadad became Jupiter Damascenus (of Damascus)

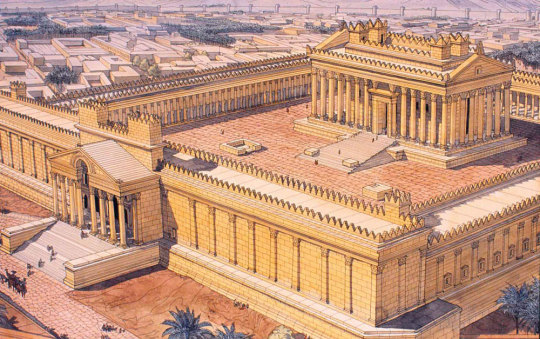

Thus, they engaged in a project to reconfigure and expand the temple under the direction of Damascus-born architect Apollodorus, who created and executed the new design. The symmetry and dimensions of the new Greco-Roman Temple of Jupiter impressed the local population. With the exception of the much increased scale of the building, most of its original Semitic design was preserved; the walled courtyard was largely left intact. In the center of the courtyard stood the cella, an image of the god which followers would honor. There was one tower at each of courtyard’s four corners. The towers were used for rituals in line with ancient Semitic religious traditions where sacrifices were made on high places.

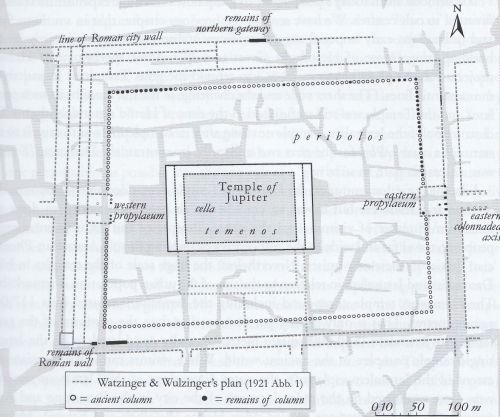

The importance of religion in the Greek-Roman world was not very significant; it is difficult to remember the name of a high priest in Greek or Roman history; at most the names of a clairvoyant such as Tiresias or an augur (a priest who interpreted the will of the gods) such as Calchas come to mind. Religion played a much greater role in Egypt and in the Near East; this may explain the size of the Temple to Jupiter in Damascus, which is enormous when compared to that of the whole town. It was preceded by two propylaea (entrances) which led to the peribolos, a high wall which surrounded the temenos, the sacred space where the actual temple was located.

The sheer size of the compound suggests that the religious hierarchy of the temple, sponsored by the Romans, wielded major influence in the city’s affairs. The Roman temple, which later became the center of the Imperial cult of Jupiter, was intended to serve as a response to the Jewish temple in Jerusalem. Instead of being dedicated to one god, the Roman temple combined (interpretatio graeca) all of the gods affiliated with heaven that were worshipped in the region such as Hadad, Ba'al-Shamin and Dushara, into the “supreme-heavenly-astral Zeus”. The Temple of Jupiter would attain further additions during the early period of Roman rule of the city, mostly initiated by high priests who collected contributions from the wealthy citizens of Damascus. The inner court, or temenos is believed to have been completed soon after the end of Augustus’ reign in 14 CE. This was surrounded by an outer court, or peribolos which included a market, and was built in stages as funds permitted, and completed in the middle of the first century CE. At this time the eastern gateway or propylaeum was first built. This main gateway was later expanded during the reign of Septimius Severus (r. 193–211 CE). By the 4th century CE, the temple was especially renowned for its size and beauty. It was separated from the city by two sets of walls. The first, wider wall spanned a wide area that included a market, and the second wall surrounded the actual sanctuary of Jupiter. It was the largest temple in Roman Syria.

Southern entrance

Eastern Propylon

General ruins:

Sources:

Post link

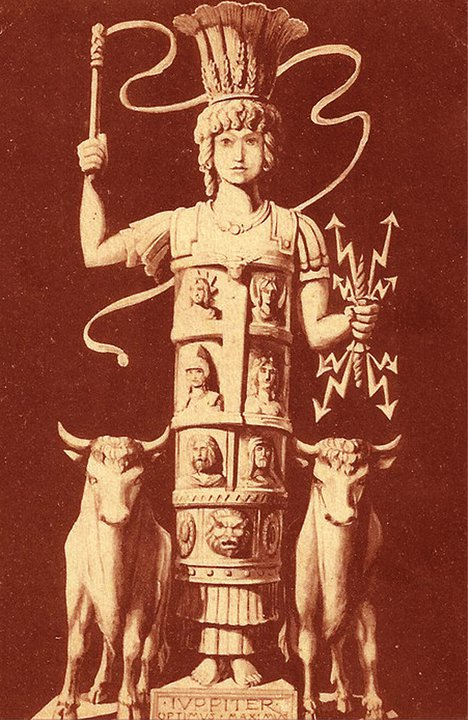

Khirbet et-Tannur

Jordan

2nd century BCE - 4th century CE

The Nabataean temple ruins atop of Jabal et-Tannur overlook the confluence of Wadi al-Hasa and Wadi La‘aban north of the modern town of Tafila. From the 2nd century BC through to the middle of the 4th century CE the sanctuary was an important pilgrimage place for the Nabataeans to worship, and celebrate seasonal rituals and banquets. With no spring for water supply, it was not a permanent settlement. It functioned in connection with the neighboring village and temple of Khirbet edh-Dharih, some 7 km south on the old caravan route coming from the capital city of Petra.

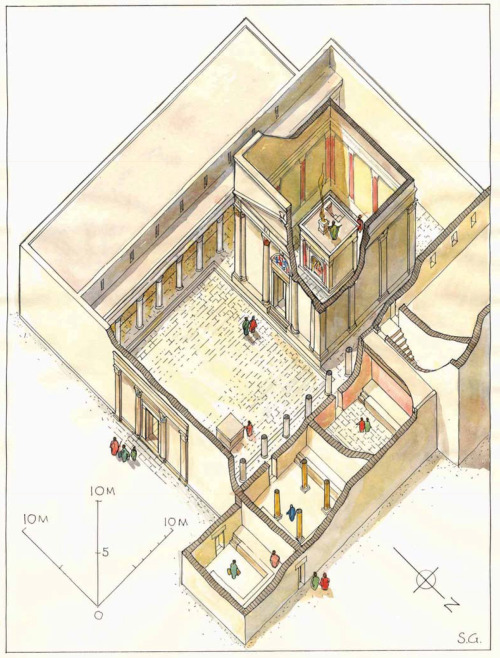

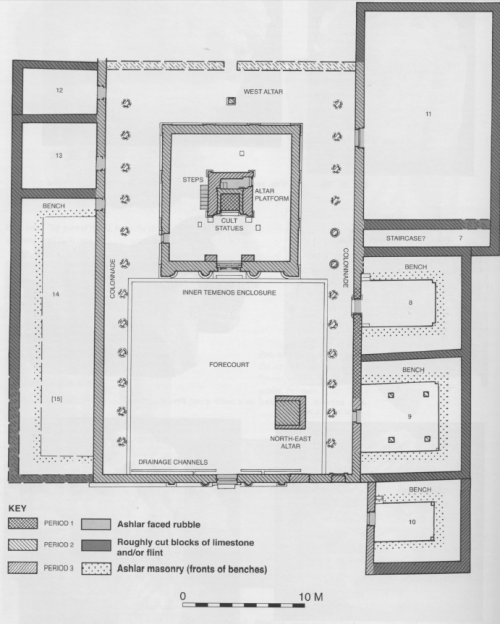

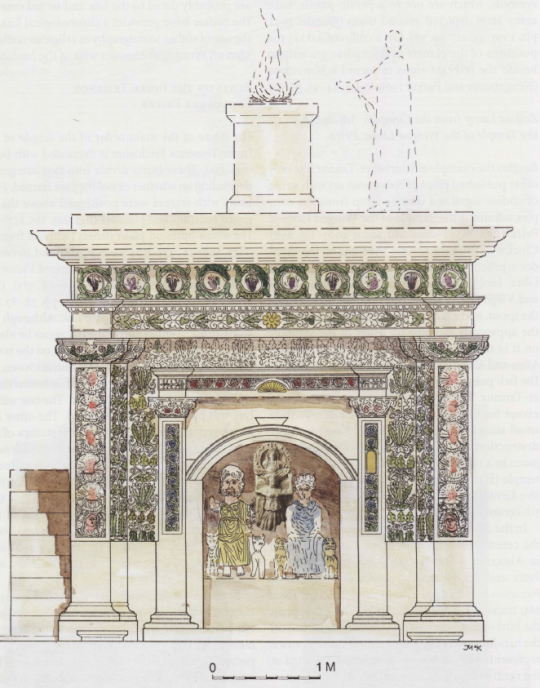

The sanctuary consisted of a temenos (temple enclosure), with a forecourt and roofed colonnaded walkways on the north and south sides connecting to rooms equipped with benches on three sides, called triclinium for resting and ritual banqueting.

The eastern façade of the inner temenos was also richly decorated. The famous relief known as the Vegetation Goddess, veiled by leaves and framed by flowers with an eagle above her comes from a semi-circular pediment over the main portal. Both sculptures are today on display at the Jordan Museum in Amman. Scholars suggest to see in her the goddess of the nearby spring of La‘aban. An inscription found on site dated 8 or 7 BC mentions building works dedicated by the guardian of this spring. After 2000 years, this name lives on in the name Wadi La‘aban, the river bed connecting Khirbet et-Tannur and Khirbet edh-Dharih.

The inner temenos (sacred area) was an unroofed square enclosure (ca. 10 x 10 m) with an altar platform in the center that had a frontal niche to host the cult statues of the main god and goddess. A male cult figure holding a lightning bolt and flanked by bull calves was found during excavations, probably the supreme god Dushara with attributes and iconography adopted by the Nabataeans from neighbor cultures. From the goddess Allat only one foot and a part of her lion throne were found. Placed between them might have been the zodiac ring encircling a bust of a Tyche, carried by a winged Victory (Nike), another one of the famous discoveries at Khirbet et-Tannur. The upper zodiac piece is in the collection of the Cincinnati Art Museum, USA, together with the main cult statues. The sculptures date from the main construction phase of the first half of the 2nd century CE. The altar niche was surrounded by an elaborate decoration including busts also representing zodiac signs, from which two have survived: the personification of Pisces (in Amman) and Virgo (in Cincinnati).

A staircase led to the altar’s roof, where a sacred flame was lit and animal sacrifices were burnt. Incense, grains and offering cakes were burnt as offerings on either side of the altar niche, and on smaller free-standing altars scattered around the site as well.

The east-west axis alignment of the sanctuary ensured that the rising sun would illuminate the altar niche during the spring and autumn equinoxes, when special rituals and celebrations took place to ensure agricultural abundance. The remains of ceramic lamps with nozzles on several levels suggest night-time processions and rituals to worship zodiacal deities appearing in the starry sky.

Post link

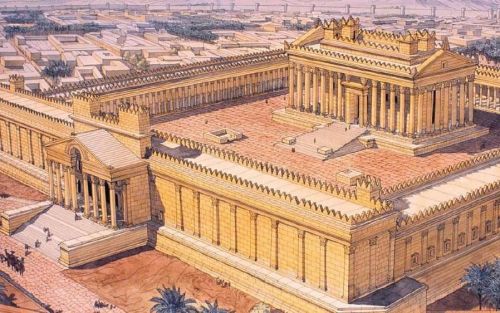

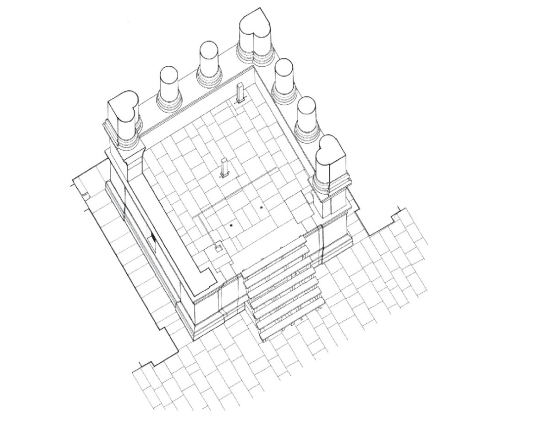

Temple of Bel (3D)

Palmyra (Tadmor),Syria

32 CE

Part I (exterior) || Part II (interior) || Part III (surrounding precinct)

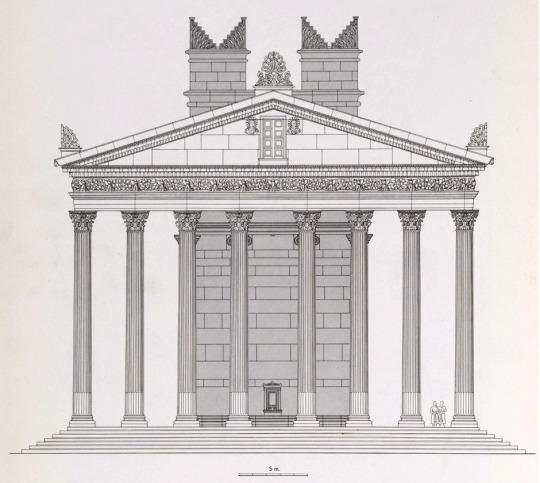

The Temple of Bel (Baal) was a temple located in Palmyra, and consecrated to the Mesopotamian god Bel, worshipped at Palmyra in triad with the lunar god Aglibol and the sun god Yarhibol, who together formed the center of religious life in Palmyra.

The temple was built on a tell with stratification indicating human occupation that goes back to the third millennium BCE. The area was occupied in pre-Roman periods with a former temple that is usually referred to as “the first temple of Bel” and “the Hellenistic temple”. The walls of the temenos and propylaea were constructed in the late first and the first half of the second century CE. The names of three Greeks who worked on the construction of the temple of Bel are known through inscriptions, including a probably Greek architect named Alexandras (Greek: Αλεξάνδρας). However, many Palmyrenes adopted Greco-Roman names and native citizens with the name Alexander are attested in the city.

A discussion of its architectural features demonstrates both the plurality of artistic and architectural styles in the ancient Mediterranean, and the numerous cultures that frequently overlapped and inter-mixed there. Although an inscription attests to the temple’s dedication in 32 CE, its completion was gradual with major architectural elements added over the course of the first and second centuries.

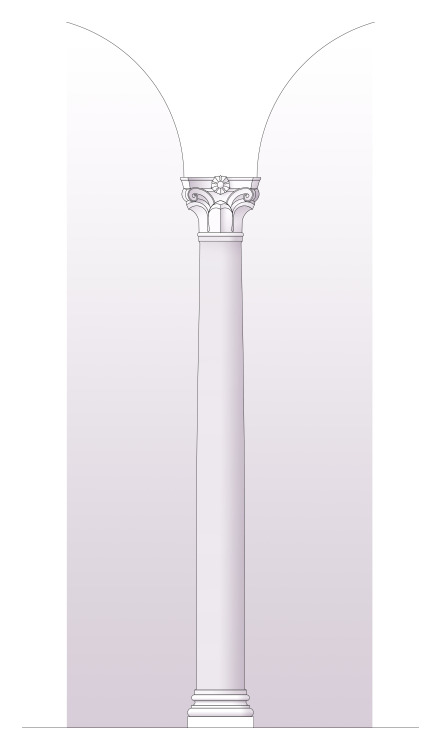

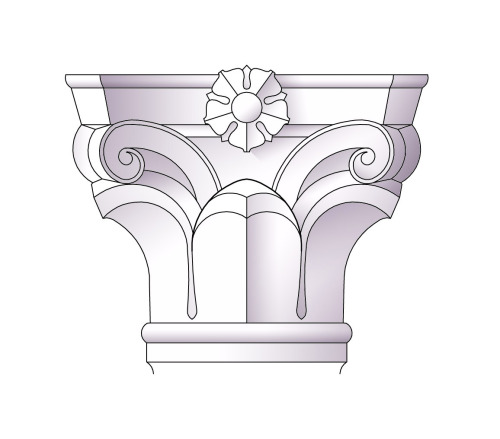

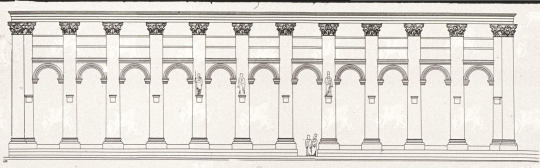

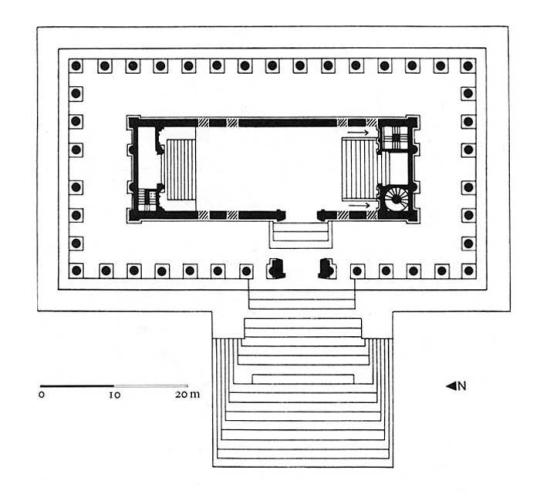

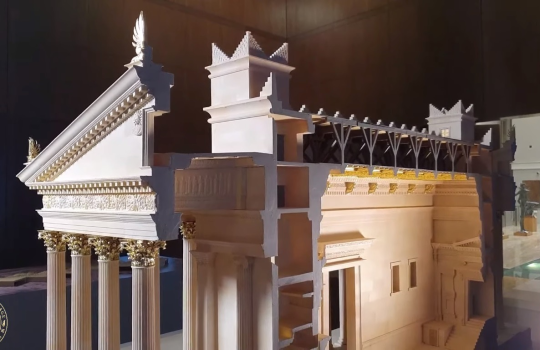

The organization of the temple’s ground plan derive from the traditions of eastern ritual architecture, including independent shrines for distinct divinities and, notably, the bent-axis approach to the cult (i.e. the architecture requires the celebrant to enter the temple and turn 90 degrees in order to view the offering table and cult area). The architectural elements employed in the temple’s elevation however, derive from the Graeco-Roman canon, including the use of the Corinthian order as well as various architectural elements of that adorn the frieze course and roofline .In its outward appearance, the temple seems to derive from the canon of Hellenistic Greek architecture .The temple itself sits within a bounded, architectural precinct measuring approximately 205 meters per side. This precinct, surrounded by a portico (a colonnaded entryway), encloses the temple of Bel as well as other cult buildings. The temple itself has a very deep foundation that supports a stepped platform. At the level of the stylobate (the platform atop the steps) the area measures 55 x 30 meters and the cella (the inner chamber of the temple that held the cult statue), stands over 14 meters in height and measures 39.45 x 13.86 meters.

Palmyra’s remarkable 2,000-year-old Temple of Bel was demolished in an atrocious crime against mankind and history in August 2015 by the Islamic militant group ISIS. (post-destruction 3D)

Fragments in the courtyard

Temple of Bel (3D)

Palmyra (Tadmor), Syria

32 CE

Part I (exterior) || Part II(interior) || Part III (surrounding precinct)

The Temple of Bel (Baal) was a temple located in Palmyra and consecrated to the Mesopotamian god Bel, worshipped at Palmyra in a triad with the lunar god Aglibol and the sun god Yarhibol, who together formed the center of religious life in Palmyra.

A discussion of its architectural features demonstrates both the plurality of artistic and architectural styles in the ancient Mediterranean and the numerous cultures that frequently overlapped and inter-mixed there. Although an inscription attests to the temple’s dedication in 32 CE, its completion was gradual with major architectural elements added over the course of the first and second centuries.

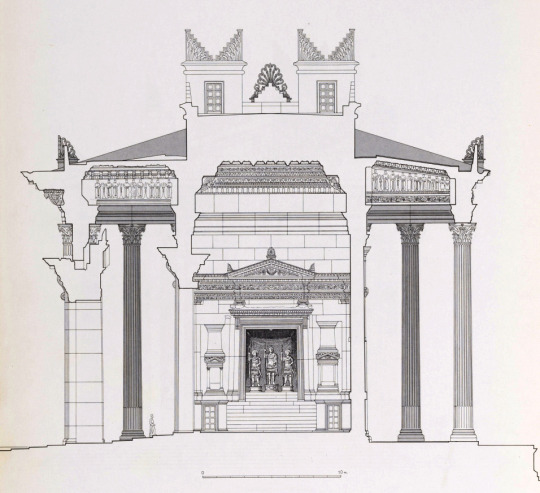

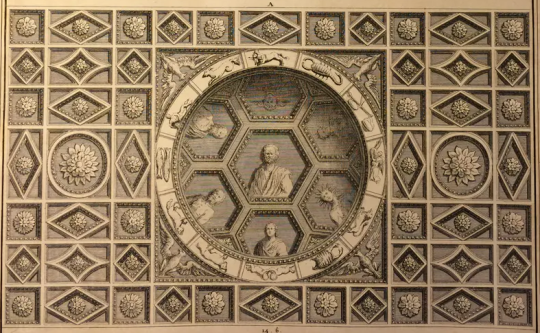

The cella is designed according to the Near Eastern tradition of the bent-axis approach and incorporates two separate shrines (thalamoi). A ramp and central stair, with an off-center doorway, grants access to the cella. The columnar arrangement is pseduoperipteral (free-standing columns at the porch with engaged columns on the sides and back) and includes an arrangement of 8 x 15 (height = 15.81 meters) fluted, Corinthian columns. The cella also has exterior Ionic half-columns at each of its ends. Merlons (crenellations) crowded the roof and the ceilings were coffered. From masons’ marks and graffiti found on the site, it seems that there were craftspeople of various background, including Greeks and Romans alongside the Palmyrenes.

Both the North and the South chambers had monolithic ceilings. The Northern chamber’s ceiling highlighted seven planets surrounded by twelve zodiac carvings as well as a camel procession, a veiled women, and what is believed to be Makkabel, the god of fertility.

Palmyra’s remarkable 2,000-year-old Temple of Bel was demolished in an atrocious crime against mankind and history in August 2015 by the Islamic militant group ISIS. (post-destruction 3D)

North adyton (3D)

South Adyton (3D)

Art

Temple of Bel (3D)

Palmyra (Tadmor), Syria

32 CE

Part I (exterior) || Part II (interior) || Part III (surrounding precinct)

The Temple of Bel (Baal) was a temple located in Palmyra, and consecrated to the Mesopotamian god Bel, worshipped at Palmyra in triad with the lunar god Aglibol and the sun god Yarhibol, who together formed the center of religious life in Palmyra.

The temple was built on a tell with stratification indicating human occupation that goes back to the third millennium BCE. The area was occupied in pre-Roman periods with a former temple that is usually referred to as “the first temple of Bel” and “the Hellenistic temple”. The walls of the temenos and propylaea were constructed in the late first and the first half of the second century CE. The names of three Greeks who worked on the construction of the temple of Bel are known through inscriptions, including a probably Greek architect named Alexandras (Greek: Αλεξάνδρας). However, many Palmyrenes adopted Greco-Roman names and native citizens with the name Alexander are attested in the city.

A discussion of its architectural features demonstrates both the plurality of artistic and architectural styles in the ancient Mediterranean, and the numerous cultures that frequently overlapped and inter-mixed there. Although an inscription attests to the temple’s dedication in 32 CE, its completion was gradual with major architectural elements added over the course of the first and second centuries.

The organization of the temple’s ground plan derive from the traditions of eastern ritual architecture, including independent shrines for distinct divinities and, notably, the bent-axis approach to the cult (i.e. the architecture requires the celebrant to enter the temple and turn 90 degrees in order to view the offering table and cult area). The architectural elements employed in the temple’s elevation however, derive from the Graeco-Roman canon, including the use of the Corinthian order as well as various architectural elements of that adorn the frieze course and roofline.In its outward appearance, the temple seems to derive from the canon of Hellenistic Greek architecture.The temple itself sits within a bounded, architectural precinct measuring approximately 205 meters per side. This precinct, surrounded by a portico (a colonnaded entryway), encloses the temple of Bel as well as other cult buildings. The temple itself has a very deep foundation that supports a stepped platform. At the level of the stylobate (the platform atop the steps) the area measures 55 x 30 meters and the cella (the inner chamber of the temple that held the cult statue), stands over 14 meters in height and measures 39.45 x 13.86 meters.

The cella was lit by two pairs of windows cut high in the two long walls. In three corners of the building stairwells could be found that led up to rooftop terraces. In the court there were the remains of a basin, an altar, a dining hall, and a building with niches. And in the northwest corner lay a ramp along which sacrificial animals were led into the temple area. There were three monumental gateways, of which the entry was through the west gate.

Palmyra’s remarkable 2,000-year-old Temple of Bel was demolished in an atrocious crime against mankind and history in August 2015 by the Islamic militant group ISIS. (post-destruction 3D)

Main gate

North side

Art from the sanctuary

Post link

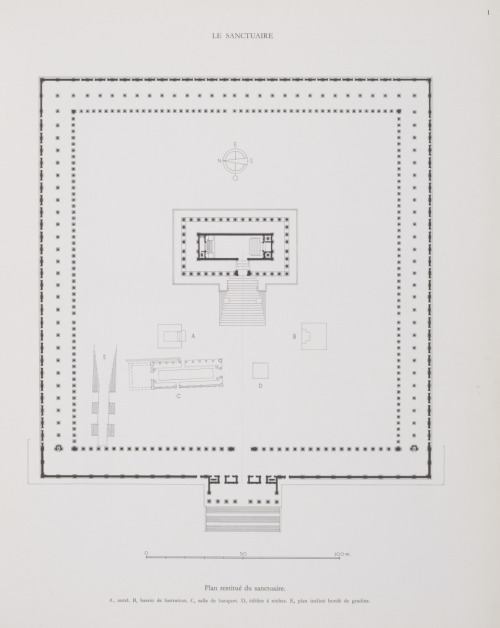

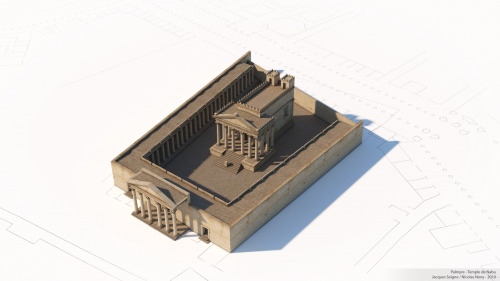

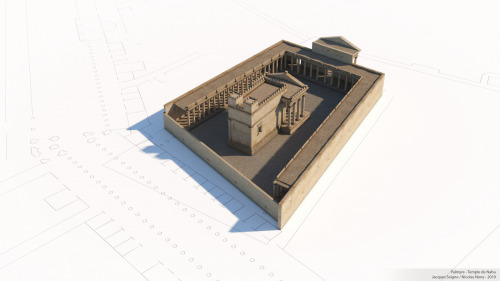

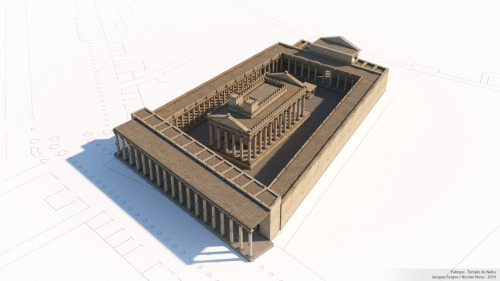

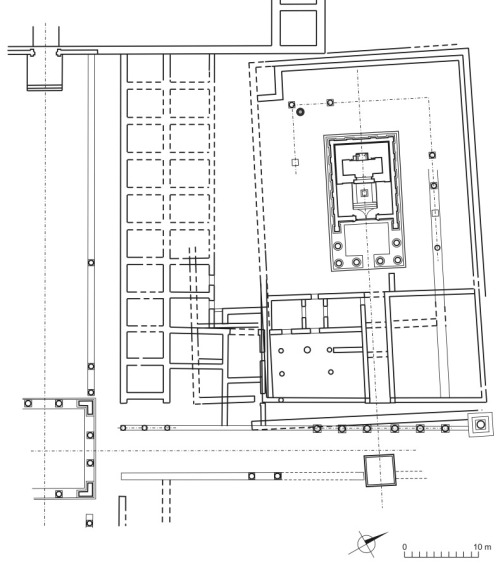

Temple of Nabu

Palmyra (Tadmor), Syria

2nd century CE

The temple was a Corinthian Hexastyle Peripteral temple dedicated to Mesopotamian god of wisdom and writing, and was Eastern in its plan; the outer enclosure’s propylaea led to a 20-by-9-metre podium through a portico of which the bases of the columns survives. The peristyle cella opened onto an outdoor altar.

The temple is characterized by its eastern style and architectural and cultural features which still exist at the site, according to Assaf.

He clarified that there are three entrances towards the long street and a main entrance in the southern side, surrounded by corridors and columns with Corinthian crowns with decorations on either side and three rooms directly connected to the inner hallway, which leads to a courtyard with a temple in center.

Post link

Temple of Allat

Palmyra (Tadmor), Syria

1st century CE

The sanctuary of Allat included a temple which is clearly younger than the temenos itself. The same is true of the temple of Ba῾alshamin, and the two are very similar to each other, even if that of Allat is preserved only in its lower courses. Both are prostyle of Roman type with a Corinthian porch of four columns in front and two intercolumnia deep, facing East, both are articulated on three other sides with pilasters, both stand on low podiums and had plain pediments in front and back.

The Lion of Al-lāt is statue that adorned the Temple, of a lion holding a crouching gazelle, was made from limestone ashlars in the early first century CE and measured 3.5 m (11 ft) in height, weighing 15 tonnes. The lion was regarded as the consort of Al-lāt. The gazelle symbolized Al-lāt’s tender and loving traits, as bloodshed was not permitted under penalty of Al-lāt’s retaliation. The lion’s left paw had a partially damaged Palmyrene inscription which reads: tbrk ʾ[lt] (Al-lāt will bless) mn dy lʾyšd (whoever will not shed) dm ʿl ḥgbʾ (blood in the sanctuary).

The temple of Allat can be dated from the internal evidence of two incomplete inscriptions as having been built in CE 148 or slightly later, barely twenty years or so after the cella of Ba῾alshamin. It is also clear that the same families were involved in the two sanctuaries. The fragmentary text from the doorway of Allat mentions two buildings: “this naos” and “the old hamana”. The latter term is Aramaic and applies to some sort of shrine. Here, for the first time, it can be ascribed with practical certainty to material remains.

These remains consist of the foundations of a small rectangular building, broader than it is deep (7.35 through 5.50 m), with very thick walls around a narrow room, barely large enough for the door wings to open inwards. This shrine has been piously preserved within the second century temple in such a way that the new walls enclose the old, leaving between them a space averaging only 6 cm wide. Stone of a different kind was used in each case. As the floor of the old building was laid practically on the ancient ground level, and as it continued to be used, the internal level of the new temple was lower than expected: the front columns set on a bench around the porch and the floor of the cella a few steps down from the porch.

The foundations of the new building also go deeper into the ground, which would have been no easy affair: they would have had to undermine the old shrine partly while keeping it intact at all costs. The cella is thus nothing more than a box containing the ancient tabernacle which remained in use as the adyton, the inner sanctum and seat of the goddess. This is apparently the only known case of such survival in Syria: usually, the adyton is built together with the temple, even if it may take the aspect of an independent building, as the two adytons of Bel, or incorporate some elements taken from the older phase, as in the case of Ba῾alshamin.

The exterior changed radically and became Classical in inspiration, Hellenistic for Bel, Vitruvian for the other two. In each case, however, these Corinthian temples were meant to impress the viewer and proclaim their belonging to the modern Roman world, but they were just a disguise. All three keep in different ways the memory of smaller, simpler tabernacles dedicated to the same godheads in the same places, but only the temple of Allat actually preserved its predecessor intact.

As the hamana of Allat remained complete, it would be pointless to roof the new cella above it. Indeed, there are good reasons to believe that the place was left open: not only has an outlet been arranged for rainwater, but more importantly, the pre-existing altar was left in front of the tabernacle but inside the temple, standing on a stone pavement not linked to either building; it could be used only if open to the sky. On the other hand, the porch should have been covered in the normal way. The narrow room inside the primitive shrine could not have any windows, as its walls are over 2 m thick. It was closed with two-winged doors which, when opened, revealed a statue inside a niche.

We have recovered several fragments of the framing, consisting of jambs covered with vine-scrolls and of a lintel featuring a spread eagle. The slab on which the statue was placed is preserved in place and bears a series of grooves and mortises suggesting a graphic restoration. This is possible thanks to several small replicas of the enthroned goddess, seated between two lions and holding a long sceptre. The statue was probably not of one piece but composite, and could perhaps have been moved from the throne to be carried in processions.

This is in sharp contrast to rituals that we can envisage for the relief images of other temples. But then, the idol of Allat was much older than the appearance of frontality in the art of Palmyra, and with it the possibility to represent the gods on a flat surface offered for viewing and veneration in other temples. Dated monuments allow us to fix the advent of frontality in the brackets between 15 and 30 CE. For its part, the idol of Allat (called “Lady of the House”), was offered by a certain Mattanai, being an ancestor of someone who mentioned the fact five generations later in 115 CE. This would bring back the original foundation to about 50 BCE at the latest (Gawlikowski 1990: 101–108).

By the same token, the first shrine of Allat becomes the oldest known in Palmyra and the first of which some remains are still in place. Another inscription found nearby mentions a hamana built in 31/30 BCE for the solar god Shamash. A square foundation 4 m to the side is still to be seen there, exactly on the axis of the Allat temple. It could have once contained a small inner room and the inscription could once have been placed in its wall, though we cannot establish this with absolute certainty. Another similar foundation was found a few years ago very close to the Allat temple. Possibly, the original temenos contained several such chapels, each for a different god. The Vitruvian cella had intruded in its midst about 150 CE without changing the character of the cult and scrupulously keeping the old installations in place.

The temple of Allat was destroyed twice: it was sacked once in 272 by the Roman troops of the emperor Aurelian and again, definitely, by a Christian mob at the end of the fourth century. In the meantime, the sanctuary remained in use within the limits of a legionary camp for over a century. One may imagine that access to it was restricted as far as the civilian population was concerned. The temple’s interior was radically changed during this time. Indeed, the old tabernacle contained within the cella had been destroyed together with the statue on the first occasion, while the walls of the cella seem to have remained intact.

At any rate, a restoration effort occurred very soon afterwards. Instead of trying to rebuild the shrine, its foundations were left in place and covered with a kind of platform including some sculptured fragments, which were thus piously preserved. We could recover some votive reliefs of the first to third centuries and some elements of the niche once framing the seated statue of the goddess. The cult image itself had to be replaced. Four short columns were brought in and set up in front of the masonry preserving the broken remains to support roofing in the form of a square canopy or perhaps a shelter from wall to wall over the whole ruin of the primitive shrine.

Under the canopy a new statue was fixed. Fallen and broken during the second sack, it has survived for the most part and could be reassembled. The statue is a second century copy of a statue of Athena, executed in Pentelic marble. It is clear that the original was Athenian and conceived in the circle of Pheidias. It has replaced an old and venerable, but no doubt primitive statue, and this in a time right after a military disaster and economic collapse. It could hardly be imported from Greece in these conditions, but could rather have embellished some profane public building in the city before receiving divine honours in the restored temple. The late restoration was probably an initiative of a Roman legionary legate under Aurelian, who wanted to reconcile the destitute local goddess, seeing in her no doubt Minerva, one of the standard Roman army cults. If so, the statue does not provide evidence for the cult of Allat, but is rather one of a series of Classical marbles imported to Palmyra for adornment of public buildings.

Post link

Giocondo Albertolli 1798. Illustration of a Corinthian Capital. Collection of the Cooper Hewitt.

#Built Beauty

Post link

The Shadow by Edmund Blair Leighton

The Shadow is based on the Greek myth of Debutades, a Corinthian girl who drew the portrait of her beloved on the wall of her bed-chamber by tracing the outline of his shadowcast by the lamp-light on the night before he departed for war. Leighton changed the setting for the drama to the battlements of a medieval castle, below which the young crusader’s ships are waiting.

“As God is my witness, I’ll never be hungry again.”

Margaret Mitchell, Gone With The Wind

I found all three! Belmont definitely likes its Corinthian columns that’s for sure. I had a much harder time finding the Doric columns. I found the Corinthian columns in front of McWhorter Hall, the Ionic columns in front of Inman Hall, and the Doric columns on the patio of the law building. We’ve got some good columns here at belmont, but it wouldn’t hurt to have a little more column diversity if you ask me.

Post link