#self help

it’s okay for you to have trouble believing in yourself - as long as you keep trying to get there, i’ll believe in you for the both of us

please try your hardest to not bottle everything up today

it’s okay to cry

there is nothing wrong with asking for help or depending on people sometimes - its okay to ask for support. you’re not alone.

try your best to not blame yourself, not everything is your fault

try your hardest to eat something today if you can - no matter how much just eat something

something different for today: try your best to fill in the blank with something positive - i am _________.

be proud of yourself

try your best to not go out of your way to just please others - do it for yourself

try your best to do what makes you happy today - if you don’t know what that is right now, that’s fine. you have time to find it, just keep trying your hardest please.

What Does It Mean To Think Catastrophically & Mindfulness Techniques To Help Overcome It

Catastrophic thinking is a type of irrational thinking, which is very common in people who suffer from anxiety disorders such as social anxiety disorder, avoidant personality disorder, generalised anxiety disorder, OCD, panic attacks and PTSD. This type of thinking usually has continuous thoughts about the future in a very negative way. These thoughts are usually what I call ‘What if?’ thoughts, and its these types of thoughts that lead to fear, dread, worry and distress. The main reason why many people with anxiety think this way is because they have a severe phobia of the unknown and what will happen to them in the future.

Psychologically speaking, these thoughts are just in our imagination from stored images from previous experiences such as traumas from our past. This is called fragmentation. After witnessing a trauma, our brains store the experience into images, which will be placed into our subconscious mind. This is the reason why some thoughts may come up and not make any sense to you or the people around you at all. Sometimes these distressing thoughts can come up in dreams and that is why many patients with PTSD and C-PTSD often have nightmares and night terrors.

However, there is a way of overcoming and healing from this dysfunctional type of thinking. Living in the present moment is the best way to heal from catastrophic thinking. This is because it gets you in tune with what is going on right now, at this moment in time - not yesterday, not tomorrow or in five or ten years from now. Knowing that you or your loved ones are completely safe at this very moment is a very good tool to use to stop disastrous thinking. Being here in the present, listening to your breath and being mindful of your thoughts and feelings will help with any kind of anxiety disorder.

As someone who has suffered from severe anxiety in the past, I have realised from my own experience that a lot of it stems from a lack of trust towards ourselves and others. When we lack trust, we start looking for reassurance and whether not we are making the right decision or not, and continuously ask for advice leading to frustration and even more doubt. This is why learning and allowing yourself to fully surrender and let go in a state of anxiety is important part of the healing process. I have previously written about trust and surrender here on this blog, if you want to read those.

Anxiety Visualisation Exercise

Close your eyes and imagine yourself sitting in the eye of a storm, the calm centre that lies behind the chaos that is going around it. You see pieces of debris floating around of all different sizes, which represent the thoughts you carry with you. Observe them and look at what they are showing to you, like you are watching a movie. You know that you are completely safe and serene in this eye of a storm and you know that it will not hurt you. Suddenly, you begin to see the storm move swiftly across, taking all of your negative thoughts with it. You feel a sense of deep peace and emotional freedom, like someone has taken a heavy bag off of your shoulders. You stand up and begin to walk towards the sun that is shining in between the clouds smiling, feeling liberated and full of joy. When you have finished this visualisation exercise, open your eyes.

If you liked this post, please share and like it with all of your friends or to someone who needs a little bit more love and support right now!

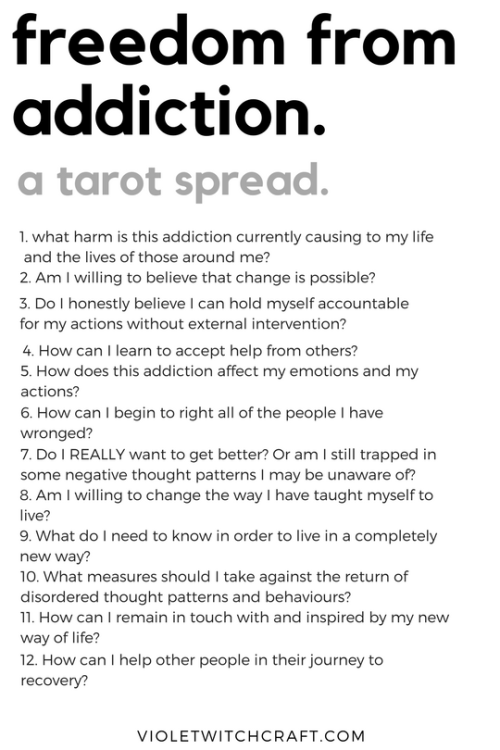

Hi Tumblr! As you might have gathered from my awful upload schedule I am a person who struggles from a large number of addictions, ranging from drugs to something as mundane as the validation of a lover. I wanted to show you a tarot method I have developed to identify when I am going off the deep end in hopes that it might bring some things to the surface of your life that you may have been avoiding.

It goes without saying that this is not a replacement for treatment and that if you suffer from any addiction no matter how embarrassing you think it might be, you need and deserve the help of others.

I’m going to try to take my own advice more often these days and I hope you do too. :)

Post link

Though it was published in 1960 as a self-help book, Maxwell Maltz’s Psycho-Cybernetics is the combination of two powerful psychological ideas. The first is that of the “self-image”, which has become well-known with the advent of cognitive behavioural therapy as well as the broader self-esteem movement. The second is the idea of the human mind as a cybernetic system. “Cybernetics” originally referred to the circuitry of guided ballistic missiles, whose navigational systems consisted of a target and positive and negative feedback mechanisms to keep in on course. In the human analogy, the goal is in response to a need or desire, and the positive and negative feedback mechanisms are our positive and negative emotions. Finally, Maltz thinks of creative imagination as the tool than can be used to influence both of the former systems to the user’s benefit and well-being. This essay will provide a summary of these main ideas and their consequences.

The idea of the self-image or self-concept might be familiar to the reader. It states that you can’t exceed the limitations you place on yourself mentally—that you believe to be true of yourself. According to theorists, the self-image prescribes the “area of the possible”. A narrow view of yourself will limit what you can do in practice, whereas an open view may allow you to excel and discover new things about yourself. What is the self-image exactly? Maltz cites the psychologist Prescott Lecky, who thought of the personality as a system of ideas that must above all else be consistent. The “ego ideal”, or self-image, is the keystone of this system. All beliefs about the world hinge on beliefs about the self. Apart from physical limitations, all limits or possibilities stem from this complex. According to Maltz, this is why plenty of “positive thinking” psychology doesn’t work. These techniques try to change a person’s thinking about their situation or environment, attacking the periphery rather than the center. As such, the changes can’t persist.

Maltz personally encountered the power of the self-image in his clinical practice as a plastic surgeon. Clients would come to him asking him to fix their disfigurements, which they believed were ruining their lives in one way or another. However, the vast inconsistency in the way that these clients responded to surgery alerted him to the psychological dynamics at play. Some clients would come to him with scars or abnormalities; some with perfectly normal and even handsome features, which they nonetheless saw as robbing them of happiness. The difference after surgery was even more striking. Some clients would seem completely transformed in terms of their personality. Some would stay exactly the same; and some would even insist that Maltz hadn’t touched a single thing with his scalpel. In addition, shame or pride about a physical feature was not universal but depended on the context. A scar across the cheek destroyed an American salesman’s confidence, but was a status symbol in the underground sabre-dueling rings in Germany at the time. This indicated to Maltz that the essential factor wasn’t the reality of a person’s appearance, but their beliefs about their appearance, and what those beliefs meant for their self-image.

This ties into a larger discussion on the power of belief in psychology. Our modern scientific-materialist ethos might influence us to believe that we naturally think in terms of what is factual and real, but it’s more correct to say that we think and act based on what we believe to be true. Belief is not a late-stage function in behaviour: Though beliefs may be derived from higher cognitive processes like reasoning, they go to form the basis of our perceptual and emotional experience. For example, you might think that the fight-or-flight reflex acts pre-consciously to real things in the environment, regardless of ideas or beliefs. But if a man encounters a bear in the woods so that his blood starts pumping and his muscles jolt into action—but the bear is actually an actor in a bear-suit—then clearly the nervous system is reacting to the idea of a bear rather than a real life-threatening situation.

The decisive influence of belief over behaviour, including subconscious or automatic behaviour, is also apparent in the twin suggestion-based phenomena of hypnosis and placebo. Under hypnosis, a weightlifter can be made to exceed their normal lifting capacity or struggle to lift a pencil. A person told that they are standing in the arctic may shiver genuinely. There are plenty of weird results to be had by suggesting an idea under the state of hypnosis. However, Maltz argues that there is no fundamental difference between behaviour under hypnosis and normal behaviour. They both simply consist of acting on what is believed to be true about oneself or the environment. In fact, in the process of changing beliefs about yourself—changing the self-image—it might be more correct to say that it’s a matter of de-hypnotizing yourself from false beliefs, provided that the new image is closer to reality. In placebo, which is the most-studied medical phenomenon and the biggest thorn in the side of pharmaceuticals, a sugar pill can have dramatic effects on a person’s somatic or mental health provided they believe they’re taking a functional, novel medicine. Most market drugs barely manage to exceed the effect produced by placebo, if at all.

The second main idea presented in Psycho-Cybernetics is that of the mind as a cybernetic system. It’s theorized that other animals also operate under the same principle. They have a goal in mind— “get food, get water, copulate”—and positive and negative emotions—gratification and lack—to motivate them and let them know how close they are to the goal. We can surmise that they have this much since the limbic system or “emotional brain” is largely conserved between humans and other mammals. However, Maltz argues that while this animal system is dictated by instinctual goals and basic needs, we have a greater capacity to consciously set new, complex goals. Indeed, the prefrontal cortex, which is enormous in humans compared to other mammals, is the seat of planning and executive decision-making (meaning its activity can influence and override other parts of the nervous system). Cybernetics comes from the Greek word meaning “steersman”, and in this theory the conscious mind is the steersman of the whole organism.

What significance does this have for the self-help domain? If the nervous system is a cybernetic system, then at least a significant portion of our positive and negative emotion is felt in relation to a goal. Happy feelings indicate we’re moving closer to our imagined destination, and sadness, anxiety, and anger tell us that we are off-course. But how many of us know what are goals are? They tend to be muddled, uncertain, or seemingly non-existent. Even worse, Maltz suggests that most people are oriented towards negative goals—towards failure. According to his take on cybernetic theory, our job as an “ego consciousness” is to submit goals to our automatic systems that then carry it out. This can be illustrated in a task as simple as picking up an object. The amount of muscle fibres and the pattern of contraction is huge and complex, but it is all taken care of subconsciously. We only need to target the object with our will—plan the broad strokes of the movement in our imagination—and the automatic systems take care of the rest. When we worry incessantly and picture our future failings and shortcomings, we are inadvertently orienting our nervous system towards this destination. What we expect to happen, what we believe will happen, will most likely happen: The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy.

Maltz offers advice on how to handle this system. For one thing, while anxiety has its uses, and was surely essential to our ancestors who had to be cautious in dangerous environments, our over-use of it manifests mostly as inhibition and failure-drive. Instead of being consumed by negative things that might happen, focus on a positive outcome. Orient yourself towards a goal that you believe will make you happy and fulfilled. Much of the fulfillment will come from incremental progress towards it, since according to the cybernetic theory, positive emotions are the positive feedback system—the “You’re on the right course” signal—but you’ll simultaneously be making progress towards a better situation. Of course, “happiness” is not the not the only—or even the recommended—goal. Any undertaking will work in the same way, whether the goal is chosen out of want, responsibility, or necessity. Picturing success and making progress towards it becomes a primary source of contentment and meaning, and picturing success rather than failure will simply make that outcome more likely.

There is also the question of how to handle the negative feedback system. In a cybernetic system, negative feedback is used to indicate error— “You’re off course”—and once the system corrects the error, it’s over. The errors are not stored in memory. Only the right course is stored so that it can be repeated later. You can observe this in infants learning to move or speak. Random, inarticulate movements are refined into the smooth, automatic movements we spoke of earlier, as the baby gropes around and moves its limbs in a trial-and-error fashion until it figures out the desired pattern. Babbling is also thought to be the expression of all possible phonetic sounds, which are narrowed down to suit what becomes the child’s mother tongue. What this is saying is that a negative experience is to be learnt from, once, and then the associated memory can be forgotten. If a bad memory persists for a long time, it might indicate that it hasn’t been used to “correct the course”. Unfortunately, some experiences can be so painful that it’s easier to push them down whenever they’re recalled. But they may dissipate if they’re taken for what they’re worth: a lesson for the future.

Another recommendation by Maltz is to use relaxation to your advantage. Armed with the knowledge that conscious-you is linked to a complex automatic mechanism, you can optimize it by simply not messing with it. Maltz cites the great American psychologist William James among others as offering the wisdom that once a goal is set and the die are cast, there is no more use in worrying. Reflecting on your actions as you’re doing them has an inhibiting and distracting effect. Anxiety clogs the gears and confuses the system. Therefore, developing a habit of relaxation, in whatever way suits you, is for the best. This might sound similar to the Taoist principle of Wu Wei, which translates to “not doing”, but more accurately means “not doing with undue effort” or “acting effortlessly”.

Maltz relates these two ideas, the self-image and the cybernetic Man, by arguing that they are both subject to modification and control by humanity’s most innovative faculty: the creative imagination. Along with our materialistic belief that our accurate perception of reality drives behaviour, we also consider our ideas and beliefs to be derived from reality. The sum of our experiences from childhood to date convince us of who we are now, and we believe that this self-image is accurate. However, from Freud onwards we’ve come to know that the line between memory and fantasy is blurred. Memories are to a large extent something that we create rather than record, and with each recollection a memory changes to suit preoccupations in the present. Though features of our self-image may have their basis in past failures or admonishments from authority figures, our self-image also has a role in how memories are recorded and reproduced. This is how a person who thinks they get nothing but misfortune doesn’t recognize good luck when it comes their way, or how someone who sees themselves as a victim is always the victim of their situation. It’s also similar to the idea of “confirmation bias”, where a person only registers or perceives what they already believe.

However, Maltz claims that we can use this blurred line between memory and fantasy, between belief and reality, to our advantage. Though nasty habits of belief or an unfortunately poor self-image can be deeply-instantiated and hard to get rid of, it’s possible through the use of imagination. Maltz argues that recollection and imagination are such similar mechanisms that our nervous system can’t tell the difference between something that is experienced and something vividly imagined. In the same way that our beliefs are abstractions from experience, we can change beliefs or create new ones by spending some time imagining ourselves, our environment, or our futures in a new light. Imagining a new self-image will instantiate it in your automatic system over time. This process doesn’t have to be equivalent with “positive delusion”. Maltz notes that most people under-sell themselves by default, and have poorer self-concepts than is realistic. Besides, trying to align value judgements with “reality” is an inherently confused affair. It usually consists of people trying to measure up to an idealized cultural standard. Maltz cites a handful of studies to illustrate the arbitrariness of the inferiority complex, including one where good students performed much worse, and experienced far more stress, when told (wrongly) that the average completion time of an exam they were given was much lower than was actually possible. Therefore, this process of achieving a reasonable self-image through prolonged imagination is what Maltz refers to as “de-hypnotizing yourself from false beliefs”.

You can also use imagination to adjust your mood at any time. By stopping to imagine a scenario in which you feel content and relaxed, you’ll feel these emotions in the present. Then, you can just stay in that emotional state and re-enter the reverie whenever you need to refresh it or escape stress. While this may sound like a cheap trick, or another instance of positive delusion, consider that worrying—which we love to do in great amounts—is the same thing with the opposite valence. You picture a negative situation and it stresses you out for an indefinite amount of time! Emotions flare up and persist. Therefore, you can modulate them by delaying negative reactions or inducing positive emotions through imagination. This is where Stoic influence comes through in Maltz’s book. And indeed, he refers to Marcus Aurelius’ claim that “Nowhere, either with more quiet or more freedom from trouble, does a man retire than into his own soul, particularly when he has within him such thoughts that by looking into them he is immediately in perfect tranquility…”.

Imagination is also the function by which we set complex goals for ourselves, intertwining it with cybernetic theory. We have already discussed how clear, positive visualisation bears differently on our automatic mechanisms than anxious, muddled imaginings. There is not much to add on this front. A cybernetic system is properly ordered when it has a target, and a positive target is going to bring more rewards than a negative one.

In this essay, I have summarized what I take to be the three main ideas in Maxwell Maltz’s Psycho-Cybernetics: The self-image and the broader influence of belief over behaviour, the human nervous system as a cybernetic mechanism, and the ways in which creative imagination can modulate both of these systems. I think the self-help value of these ideas is immense, and might as well be the beginning and end of the self-help field. Most self-help books I’ve observed or explored seem to have content that appears insightful at first, but is quickly forgotten. In distilling out the psychological ideas that made Psycho-Cybernetics great, I’ve hoped to help people remember the insights by focusing on core principles and elaborating a framework rather than a method. There are plenty of methods to be found in the original book, but I think there is just as much benefit in incorporating these ideas into everyday life in one’s own personalized way.

Works cited:

Maltz, Maxwell. Psycho-cybernetics: A New Way to Get More Living Out of Life. N. Hollywood, Calif: Wilshire Book, 1976. Print.

Happy Pub Day to Start Now: Because That Meaningful Job Is Out There, Just Waiting For You by Reynold Levy! This book will help you think about your future creatively and prepare for it resourcefully.

Purchase from these retailers!

Amazon:https://amzn.to/3a5X6mN

Indiebound:http://bit.ly/2TuTe8G

Post link

realizing i spend too much time worrying about embarrassment. i don’t know something? that’s okay. i haven’t seen that movie or know about that book? that’s okay. i do something that makes my life easier that people consider the “lazy way”? that’s okay. i like this harmless thing people think is “cringe”? that’s totally okay. it’s a waste of energy to criticize myself because of the judgement i anticipate from others.

don’t mistake people being rude and judgement for constructive criticism. life is too short to be concerned with rude assumptions that don’t truly say anything about you or your character.

being sensitive doesn’t make you over sensitive. it’s okay to feel and to react.

i sometimes forget there aren’t official rules for what you have to know as an adult. don’t need to read the latest ny times bestseller, don’t need to know the differences between wines, don’t need to have seen all the cult classic movies, don’t need to have endless crazy fun college stories. i know not everyone feels this pressure, but as i’m getting older, sometimes it feels like i have to fake knowing certain experiences. and i really don’t.

You are an undiscovered miracle.

You are not who you think you are.

You are smarter, stronger, and more brave than you think you really are.

Give yourself a chance to surprise yourself and the world.

You have a lot of undiscovered greatness inside of you.

So believe in yourself and be confident, for you can shine brighter and achieve higher.