#fun facts

The 1970s: A Decade of Change

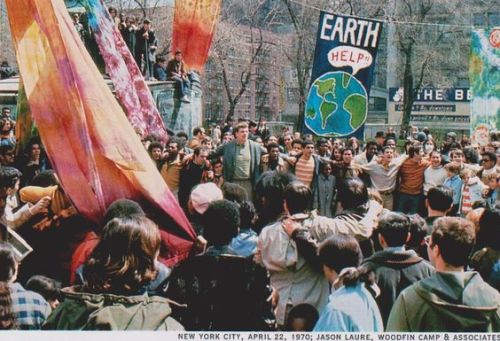

1. Earth Day 1970, New York City. National Geographic

2. Highway picnic during the Oil Crisis, 1973

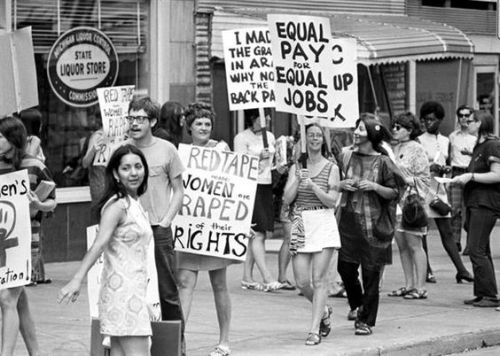

3. Women protest for equal pay, Detroit, 1970

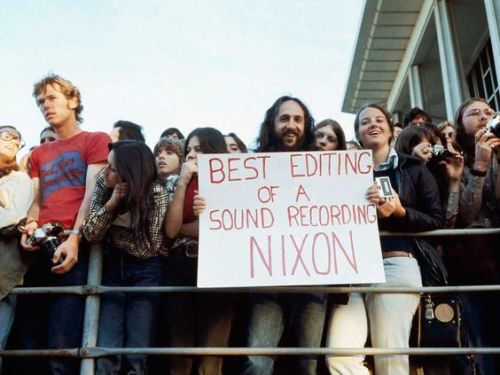

4. A spectator holds up a sign at the Academy Awards, 1974

5. Kent State Shootings, 1970

6. Protesters on Ireland’s Bloody Sunday, 1972

7. Sammy Davis Jr. performs for members of the 1st Cavalry Division, Vietnam, 1972

8. Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsberg at Jack Kerouac’s grave, Edson Cemetery, Lowell, Mass. 1975. Ken Regan

Post link

limerence

A quote from Lynn Willmott’s 2012 book, Love and Limerence: Harness the Limbicbrain, describeslimerence as ”an involuntary potentially inspiring state of adoration and attachment to a limerent object (LO) involving intrusive and obsessive thoughts, feelings and behaviors from euphoria to despair, contingent on perceived emotional reciprocation.”

The term was coined by psychologist Dorothy Tennov to concisely point to a concept she had discovered during some of her studies in 1960s. She used it first in a book written in 1979 entitled Love and Limerence: The Experience of Being in Love.

Limerence differs from love by being a state of unhealthy obsession, a “compulsory longing for another person,” as put by Albert Wakin at Sacred Heart University.

I was hoping to find some etymology on the word, but it looks like it was arbitrarily created by Tennov. The morphemic ending -encedenotes the word as describing a state of being, although limer-doesn’t have any historical meaning of its own.

Still, I think it’s an interesting word.

euouae

Euouae’sclaim to fame is as the longest word in the English language which is composed entirely of vowels.

It actually came to be as a mneumonic device in medieval music. There is a portion of the Gloria Patri which is “Seculorum Amen,” and it occurs frequently in the hymn. If you notice, euouaeis the string of vowels pulled directly out of the words: SeculorumAmen.

Instead of writing out the entire phrase every time, music writers would leave euouaeunderneath the notes to indicate to the choir what they were expected to sing.

As described in A General History of the Science and Practice of Music by John Hawkins in 1853: "a word, or rather a compages of letters, that requires but little explanation, being nothing more than the vowels contained in the words Seculorum Amen; and which whenever it occurs, as it does almost in every page of the antiphonary, is meant as a direction for singing those words to the notes of the Euouae.“

ladybug

I wasn’t quite intending for this post to be so involved, but I happened upon an article which said that in Welsh, you can call ladybugs buwch goch cwta, which translates to English as “little red cow,” which I think is absolutely adorable.

buwch: from the Middle Welsh buchmeaning cow, ultimately a derivative of the Proto-Indo-European root gwou-, meaning cattle

goch: a mutation of the adjective coch,from the Latin coccummeaning “scarlet, berry, dye or dyed red,” from the Ancient Greek term κόκκος kokkos, which is a “grain, seed or the color scarlet”

cwta(I’ve also seen it spelled gota), means “short or little,” and is supposedly borrowed from a Middle English term which meant “to cut down”

It turns out, though, that the name for these beetles is actually quite complicated in a lot of European based languages.

First, to look at the taxonomic family name coccinellidae.This comes from the Latin coccineusmeaning “coloured scarlet,” a term which you can also see in the Welsh, it is the same root from which we get coccumand eventually goch.There are a few other descendants of this term in nearby languages as well, like the French coccinelleand the Italian coccinella.

However, obviously, that’s not where we get the English name ladybug.In Old English, they were called lady cows (again a nod to the Welsh), in which cowwas a comment on it’s spotted wings and ladywas in reference to the Virgin Mary. The seven black dots displayed on its back were believed to have been symbolic of her seven sorrows as are described in Christian scripture.

Although English uses the more ambiguous lady, many languages have retained the Mary portion in the modern name, like Catalan marieta, Danish mariehøne(literally “Mary chicken”) and German Marienkäfer(literally “Mary beetle.”)

I have absolutely no idea what chickens have to do with anything, but good job Danish, I like it.

melancholy

I’m not quite sure why, but I tend to use this word quite frequently. I feel as though sadisn’t quite broad enough to encompass the “dispirited depression” I find in melancholy.In Old English, the word more exclusively referred to an illness associated with too much black bile in one’s body, a substance which was believed to have been secreted by the spleen.

The contemporary emotional meaning appeared in the Middle English as melancolie,a direct borrowing from the Old French, which was adopted from the Ancient Greek melankholía.This word is a compound of the two terms μέλας melas “black, dark, murky,” and χολή khole“bile.”

Interestingly, although this literal translation for the Greek is “black bile,” which we can see resurfaces in the English traditions, it was used more closely to the way we use melancholynow, as “atrabilious, gloomy.”

To circle back to a previous note, we can trace back μέλας a little further to the Proto-Indo-European root mel,meaning “to grind, hit,” but also “dark, dirty.” The other half, χολή, can be attributed to ghel, meaning “gold, flourish, pale green, shine.” Although it has this seemingly pleasant definition, it is cited as being the ancestor for many languages’ terms for “bile, gall, fury, rage, disease, etc.”

fancy

Fancy,in the adjective sense of pressed linens, champagne and marble, feels less interesting than the verb varieties: “to believe, to visualize or interpret as,” and my favorite, “to like or have a fancy.” I think the sound of fancyingsomeone is sweet, like you consider them as being of a special elegance and loveliness.

What I quite like about this word is that it is apparently a contraction of the word fantasy.Around the 15th century, it was originally spelled fantsy, specifically adopting the meanings of “whim, inclination.” Our current definitions of “fine, elegant,” appeared later.

The Middle English fantasy (also spelled fantasye), came from the Old French fantasie,from the Latin phantasia, meaning “a notion, phantasm, appearance, perception.” The root Greek was the term φαντασία phantasía,a derivative of the verb φαίνω phaínō,which is “to make visible, to bring to light, to cause to appear.” You might notice its similarities to the related word for “light,” φῶς phôs,from which we get other English words like photograph,photon, etc.

Ultimately, these are all attributed to the Proto-Indo-European root bheh-or sometimes bha-,meaning “to shine.”

aurora

“A luminous phenomenon that consists of streamers or arches of light appearing in the upper atmosphere of a planet’s magnetic polar regions and is caused by the emission of light from atoms excited by electrons accelerated along the planet’s magnetic field lines” - Merriam Webster Dictionary

I’m sure to someone with a different degree, this makes sense, but I interpret aurorato mean exclusively, “pretty northern lights.”

The English comes from the Latin word Aurora,the name of the Roman goddess of dawn. She is called the daughter of Hyperion and Euryphaessa, who assisted in bringing the sun to shine in the mornings.

The Proto-Indo-European root is au̯es-, meaning “to shine, gold, morning, etc.” Interestingly, this also birthed the Greek word Ἠώς Ēṓs,a parallel of the Latin word, and the Greek name for the same deity. From ἠώς, we have eastandEaster,both of which make sense. The dawn rises in the east, and the word Easter is a derivative of a Germanic goddess of the dawn.

The Moirai, or Fates, are the three goddesses of the Greek pantheon who determine the path of human destiny. With such a role, they are considered both goddesses of birth and of death, arriving when a person is born to assign them their fate, and again when they die to end it.

The oldest stories called them one collective power of Fate, namely Aisa:

Aisa - Αἶσα, the abstract concept of “fate,” related to the verb αἰτέω aitéō, which is “to ask, crave, demand, beg for”

However, in later accounts the three individual deities were separated, each performing a certain function, to form the trio of the Moirai:

Moirai - Μοῖρα, from the Ancient Greek μοῖρα moîra, “part, portion, destiny,” the verb form is μείρομαι meíromai, which means “to receive as your portion, to accept fate,” possibly from the Proto-Indo-European root smer-meaning alternately, “to remember, care for” and “allotment or assignment”

In Theogeny of Hesiod, they’re called both the children of Zeus and Themis, but also daughters of Nyx, the night:

“Also she [Nyx] bare the Destinies and ruthless avenging Fates, Clotho and Lachesis and Atropos, who give men at their birth both evil and good to have, and they pursue the transgressions of men and of gods: and these goddesses never cease from their dread anger until they punish the sinner with a sore penalty.”

Clotho - Κλωθώ, from the Ancient Greek verb κλώθω klótho,which is literally “to spin (as in wool or cotton), twist by spinning;” the youngest fate and the spinner of the thread of life

Lachesis - Λάχεσις, related to the Ancient Greek verb λαγχάνω lankhánō,which means “I obtain, receive by drawing lots, assigned to a post by lot,” the root for which may be the noun λάχος lákhos,“lot, destiny, fate;” the second fate, measurer of the thread of life

Atropos - Ἄτροπος, literally meaning “unchangeable,” compounds the prefix ἀ- a-(”gives it’s host the opposite of the usual definition, similar to English un-, as in wisetounwise”) and the verb τρέπω trépō,which is “I turn,” likely from the Proto-Indo-European root trep-, “to turn or bow one’s head (possibly out of shame);” the eldest fate, bearing the sharp shears which sever the threads of life, also known as “inevitable”

efflorescence

I can’t quite put my finger on it, but I love words ending in -escence. It makes the whole thing feel ethereal and oddly immaterial.

For example, we have the word efflorescence,meaning “blooming, apt to effloresce, being in flower.” It’s borrowed in its entirety from the French, which is itself from the Latin efflorescere, “to bloom, flourish.” The Latin is a compound of the prefix ex- “out of” andflorescere “to blossom,” from the Latin noun flos, “flower.”

The Proto-Indo-European root for flosis apparently *bhel, which means “to thrive or bloom.” Interestingly, it may be a variant of another form with the same spelling meaning “to blow or swell.” Regardless, this seems to be the ancestor whence such words as flora, flourish, bloom etc, as well as Irish bláth “flower,” and Old English blowan “flower.”

caricia

Although we have the Englishcaress, I personally like the sound of the Spanishcaricia much better. It feels more intimate somehow?

The romantic root for both of these is the Italiancarezza (interestingly, the English is a layer removed, coming through the Frenchcaresse).Carezza, meaning “caress or pet” is from the Italian nouncaro, which is “dear, beloved, precious, sweetheart” or alternately, “expensive.” The -ezza is a sort of nominalizing suffix. The Latin predecessor iscarus of the same meaning.

Depending on the source, the Proto-Indo-European root is written as either-kehor-ka, “to desire or to wish.”Cherish is another sweet word from the same PIE.

aisling

Aisling is in my opinion, a beautiful word which exists in both English and its native Irish. In English (IPA: ˈæʃlɪŋ, aehsh - ling),aisling refers to a poem which includes a dramatic illustration of a dream or vision. More specifically, it refers to a form of Irish poetry which was sometimes used for political ends in the 17th and 18th centuries.

It is a direct borrowing from the Irish aisling(IPA: aʃlʲɪɲ),which more broadly translates to “dream or vision.” This comes from the old Irishformaislinge of the same definition.

Another version of the word I really like is the nounaislingeach, which is a combination of the verb form ofaisling meaning “to see in a dream or vision, and the nominal suffix -ach, which comes together to create “visionary or daydreamer.”

Although the word is spelled in many different ways (púca, pooka, pwwka, etc), I’ll look specifically at the púca form. In Irish folklore, a púca is a shapeshifting goblin which can choose it’s form as it pleases. Some of the more famous stories involve them appearing as a black horse with glowing, golden eyes. However, they might also be seen in the shape of a dog, rabbit, or perhaps an elderly man. They’re particularly mischievous creatures and are usually encountered at night.

Púca comes from the Old Irish púca, which means “goblin or sprite.” This is probably from the Old English pūca, “spirit or demon.” A proposed Proto-Germanic root is pūkô, from the Proto-Indo-European spāug-, meaning “brilliance, spectre.”

Another theory ties it to the Indo-European root beuwhich relates to “puffing, swelling.” This evolved into terms for “swelling, growths, blisters, mucus,” and from here into Old English for “demons, parasites, bugs.”

Despite being now quite archaic, there is an English cognate for púca, which ispuck, a clear derivative of the Old English.Puck is used as “a mischievous fairy or sprite;” you might recognize it also as the name of Shakespeare’s infamous A Midsummer Night’s Dreamcharacter.

amatorculist

It is listed in A New Universal Technical Etymological and Pronouncing Dictionary of the English Language by John Craig, 1854 as:

AMATORCULIST, a-ma-tor'ku-list, s. (amatorculus, Lat.) A little pitiful insignificant lover; a pretender to affection.

As stated, it’s a close borrowing from the Latindiminutive phrase amatorculus, which means literally “little lover.” A Latin Dictionary by Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short adds the note, “a little, sorry lover.” It is a compound of the nounamator “lover, someone who loves,” and the suffix -culus, which creates the diminutive sense, like a familiar or pet name.

Amator is the noun actor of the verbamare, which means “to love.” Interestingly, this is actually also the word we borrowed both the French and English cognatesamateur from. Although we sometimes useamateur in English in a sort of derogatory way, the original meaning is purely taken from the Latin: “a lover of something, someone who does something for the sake of enjoyment.”

I’ve just about never been able to spell this word correctly, I always want to put ana in place of the finale. The word comes from the Middle English forms simeterie,cymytory, and cimitere, which began to be spelled with cem- around the 15th century. The words came through French from the Latin coemeterium, which originated the meaning of “burial ground for the dead.”

The Greek κοιμητήριον koimētḗrion, was more or less free of the sense of mortality and meant simply “sleeping chamber” or “dorm.” Interestingly, it derived from two verbs, κοιμάω koimáōand κεῖμαι keîmai. The first meant “to put to sleep,” while the second meant “to lie.” The morbid connotation seems to have been stronger in this second verb κεῖμαι, which had a variety of interpretations including, “to lie asleep, idle,” “to lie sick or wounded,” “to lie dead, “ and “to lie neglected or unburied.”

Before this particular linguistic thread arrived in English, though, the Old English word for burial ground was licburg, a construction using the noun lic, which meant “corpse, dead body.” They may have also used lictun, which comprised of lic “corpse” + tun “enclosure, yard.”

cordial

An adjective meaning “characterized by pleasantness, friendliness, sincerity, or comfort, reviving.” The original, but now obsolete definition was “something relating to the heart;” this has since been transferred onto the word cardiac, leavingcordial with the specifically figurative and whimsical sentiments.

Both the English cordial, and its identical French cognate come from the Latincordialis, which is itself from the Latincor, meaning “heart or soul/spirit.” The possible Proto-Indo-European root is *kerd, “heart,” from which we get many modern words like French cœur and Spanish corazón.

Another English definition forcordial is the less common noun version referring to “a liqueur or sweet tasting medicine.” This is from the 1600s, which I think makes some sense relating to its adjective form as something that revives, invigorates or comforts.

ineffable

Perhaps at the moment best associated with Good Omens,ineffable is an adjective first used in the 14th century meaning “unspeakable, incapable of being expressed with words.” It comes from the Latinineffabilis, which comprises the morphemesin “not” + effort “to utter, say” + bilis “able to be or do.” The Latin was a little less grandiose in meaning, and described things which were “unutterable or unpronounceable.”

Interestingly, the Latin verbeffort which appears inineffabilis is actually a compound of the prefixex meaning “out, away, through or up,” andfor which is the word for “to say, talk, speak.”

kiss

Though Middle English had the meaning of a reciprocal kiss, the Old English wordcyssanwas defined as a “touch of the lips, in reverence or respect.” The English likely comes from the Proto-Germanic *kussijanaor*kussjan, a word compiled of*kussaz, meaning “kiss,” and the suffix *jana. Cognates include the Swedishkyssa, the German küssen and the Gothickukjan.

Although beyond this there is not an agreed upon root for Indo-European languages, there is typically a supposedly onomatopoeic *ku sound, which exists in Greek and Sanskrit as well. This is not always the case though, as in the instance of Latin suāviārī (meaning “to kiss,” but related to suāvis meaning “sweet, pleasant, delicious,”) and bāsium, (ancestor of Spanishbesar, and meaning “kiss, particularly of the hand”).

Koios - Κοῖος, possibly from the Ancient Greek ποῖος poios, an interrogative adjective for “of what kind, which;” the titan of intelligence and the north pole

Kreios - Κρεῖος, the Greek word for ram, relating him to the constellation Aries; the titan of the south

Kronos - Κρόνος, said to be the same as χρόνοςkhronos, which was both the Ancient Greek for “time, period, term,” and the name of the personified deity of time in Greek mythology; the titan who destroyed his father Ouranos and came to rule during the so named Golden Age of the cosmos, Cicero explained the story of Kronos consuming his children after their birth to be allegorical to the manner in which time devours the years and matter of ages past

Hyperion - Ὑπερίων, a compound of the Ancient Greek ὑπέρhuper, meaning “above, over, across,” and -ῑ́ων -ion, a masculine patronymic suffix. ὑπέρmay have come from the Proto-Indo-European root upér of the same definition, the interpretation being: “him who goes to or regards from above;” the titan of heavenly light, fathered Eos the dawn, Helios the sun and Selene the moon, associated with the east

Iapetos - Ἰαπετός, from the Ancient Greek for the piercer or wounder, meaning “javelin” in modern Greek; the titan of mortality and mortal life, associated with the west

Mnemosyne - Mνημοσύνη, probably another form of μνήμη mneme, meaning “memory,” from the verb μνάομαι mnaomai, which is “to be mindful of, to remember,” derived from the PIE *men-, “to think;” the titan of memory and remembrance, the mother of the muses

Oceanos - Ὠκεανός, possibly of a non-Indo-European, pre-Greek linguistic origin; the eldest titan, represented the river, ocean, and heavens which were believed to have risen and set into his waters

Phoebe - Φοίβη, the feminine form of the masculine ΦοῖβοςPhoibos, a name meaning “pure, bright, radiant,” possibly from the PIE root *bʰeigʷ-, meaning “ to shine, clear;” the titan of prophetic radiance, often either confused with or connected to Artemis and Selene

Rhea - Ῥέα, of uncertain etymology, possibly connected to ἔρα éra, meaning “earth, ground,” which might connect the name to the PIE root *er, also “earth.” sometimes connected to the Ancient Greek ῥόα rhóa, the word for “pomegranate” or ῥέωrheo, which is “to flow;” the titan of fertility and motherhood, mother of the gods

Tethys - Τηθύς, possibly from the Ancient Greek τήθη thethe, meaning “grandmother;” the titan of fresh water, mother of the oceanids

Theia - Θεία, probably meaning “aunt,” though she is also called Euryphaessa, a compound of the words εὐρύς eurus, “wide,” and φάος phaos, meaning light as both literal “daylight or shine,” and the metaphoric “light of joy, delight, victory, etc;” the titan of shining light, metal or jewels, mother of the sun, moon and dawn

Themis - Θέμις, the Ancient Greek word for “law, order, custom,” possibly connected to the PIE root*dheh, meaning “to do, put or place;” the titan of divine law and order, the mother of the moirai and horae, or the fates and seasons

Wretch derives from the Old English nounwræcca, meaning “stranger, exile,” not unrelated to the verbwreccan, “to drive out, punish.” The Germanic root whence it came,*wrakjan, “someone pursued, exile,” is interestingly also related to the Old Saxonwrekkio and to the Old High Germanreccho, “person banished, adventurer.” From this branch, we get the modern GermanRecke, which has the much more powerful and positive connotation of “warrior.”

Also related to (but not directly derived from) the Old English wreccan is the modern Englishwreak, as in, to wreak havoc. Oddly enough, the two wordswreakandwretch semantically make some sense together: their respective Proto-Germanic roots mean “to drive out or pursue” (*wrekanan) and “one pursued” (*wrakjan).

An aside: I had the idea to research this word after I recently reread Frankenstein by Mary Shelley, where it occurs 66 times. I suppose that’s not overmuch, but it definitely wormed its way into my brain.

Virgo: It’s likely that the holiday season isn’t your thing, and it can be hard for Virgo’s to appreciate and really experience the Sagittarian goodness at this time. Happiness can be being able to complain in peace, and this could certainly be something you do a lot of this season.

Aries:Sagittarius may try to take you down a notch and put you in your place, and you’re going to thank those lucky stars for the opportunity. You’ve probably been burning the candle at both ends all year long, and Sagittarius is going to come and mellow you out, getting you on the right foot for next year.