#catalysts

Novel use of NMR sheds light on easy-to-make electropolymerized catalysts

In the world of catalytic reactions, polymers created through electropolymerization are attracting renewed attention. A group of Chinese researchers recently provided the first detailed characterization of the electrochemical properties of polyaniline and polyaspartic acid (PASP) thin films. In AIP Advances, the team used a wide range of tests to characterize the polymers, especially their capacity for catalyzing the oxidation of popularly used materials, hydroquinone and catechol.

This new paper marks one of the first pairings of standard electrochemical tests with nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis in such an application. “Because these materials can be easily prepared in an electric field and are cost-effective and environmentally friendly, we think they have the potential to be widely used,” said Shuo-Hui Cao, an author on the paper.

Although PASP has shown excellent electrocatalytic responses to biological molecules, newer areas of inquiry have explored the material’s ability to lower the oxidational potential in oxidation-reduction reactions. Reducing the oxidation potential is key for finding further uses for two materials used extensively as raw materials and synthetic intermediates in pharmaceuticals, hydroquinone and catechol.

Post link

Light makes Rice U. catalyst more effective: Halas lab details plasmonic effect that allows catalyst to work at lower energy

Rice University nanoscientists have demonstrated a new catalyst that can convert ammonia into hydrogen fuel at ambient pressure using only light energy, mainly due to a plasmonic effect that makes the catalyst more efficient.

[…]

A study from Rice’s Laboratory for Nanophotonics (LANP) in this week’s issue of Science describes the new catalytic nanoparticles, which are made mostly of copper with trace amounts of ruthenium metal. Tests showed the catalyst benefited from a light-induced electronic process that significantly lowered the “activation barrier,” or minimum energy needed, for the ruthenium to break apart ammonia molecules.

The research comes as governments and industry are investing billions of dollars to develop infrastructure and markets for carbon-free liquid ammonia fuel that will not contribute to greenhouse warming. But the researchers say the plasmonic effect could have implications beyond the “ammonia economy.”

Post link

Researchers uncover basics of common industrial catalytic processes

Catalysts are used in a wide variety of industrial processes around the world in everything from the production of medicines, fertilizers, plastics, and other household products to the processing of fossil fuels.

They speed up chemical reactions with the aim of minimizing energy usage. But while they are critically important, catalysts have often been developed through trial and error or tradition rather than through scientific principles.

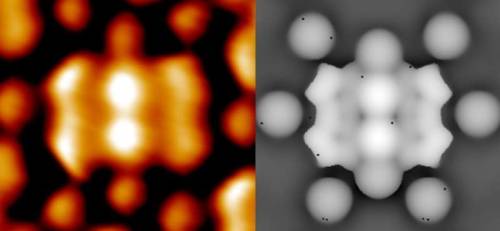

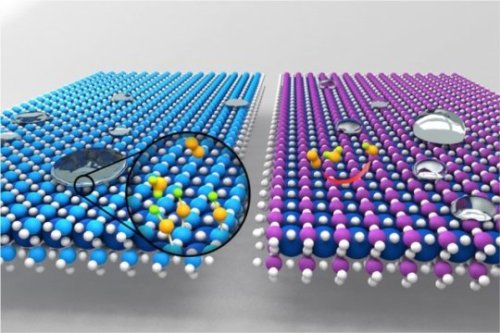

Using a combination of microscopy and spectroscopy to get real-world imagery as well as sophisticated theoretical calculations, Washington State University researchers collaborated with Prof. Junfa Zhu from the University of Science and Technology of China to unravel an underlying mechanism of a catalytic reaction at the atomic level.

The work, published in the journal of the American Chemical Society, JACS, improves fundamental understanding of reactions that could someday lead to more efficient industrial processes.

Post link

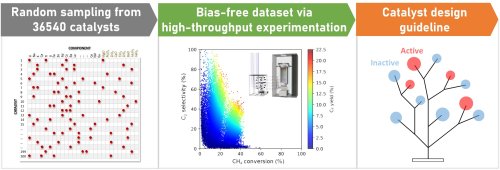

Thanks to machine learning, the future of catalyst research is now

To date, research in the field of combinatorial catalysts has relied on serendipitous discoveries of catalyst combinations. Now, scientists from Japan have streamlined a protocol that combines random sampling, high-throughput experimentation, and data science to identify synergistic combinations of catalysts. With this breakthrough, the researchers hope to remove the limits placed on research by relying on chance discoveries and have their new protocol used more often in catalyst informatics.

Catalysts, or their combinations, are compounds that significantly lower the energy required to drive chemical reactions to completion. In the field of combinatorial catalyst design, the requirement of synergy—where one component of a catalyst complements another—and the elimination of ineffective or detrimental combinations are key considerations. However, so far, combinatorial catalysts have been designed using biased data or trial-and-error, or serendipitous discoveries of combinations that worked. A group of researchers from Japan has now sought to change this trend by trying to devise a repeatable protocol that relied on a screening instrument and software-based analysis.

Post link

Producing ammonia through electrochemical processes could reduce carbon dioxide emissions

Ammonia is commonly used in fertilizer because it has the highest nitrogen content of commercial fertilizers, making it essential for crop production. However, two carbon dioxide molecules are made for every molecule of ammonia produced, contributing to excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

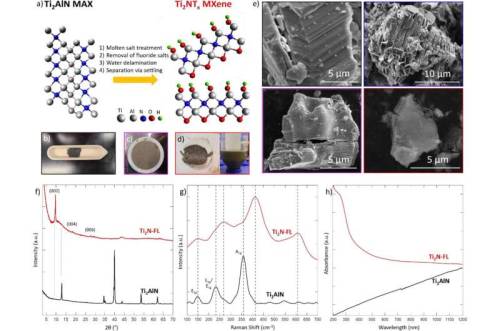

A team from the Artie McFerrin Department of Chemical Engineering at Texas A&M University consisting of Dr. Abdoulaye Djire, assistant professor, and graduate student Denis Johnson, has furthered a method to produce ammonia through electrochemical processes, helping to reduce carbon emissions. This research aims to replace the Haber-Bosch thermochemical process with an electrochemical process that is more sustainable and safer for the environment.

The researchers recently published their findings in Scientific Reports.

Since the early 1900s, the Haber-Bosch process has been used to produce ammonia. This process works by reacting atmospheric nitrogen with hydrogen gas. A downside of the Haber-Bosch process is that it requires high pressure and high temperature, leaving a large energy footprint. The method also requires hydrogen feedstock, which is derived from nonrenewable resources. It is not sustainable and has negative implications on the environment, expediting the need for new and environmentally friendly processes.

Post link

New strategy to control distribution of acid sites in zeolites

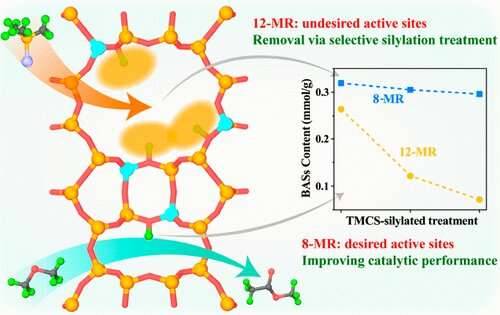

Zeolites are one of the shape-selective catalysts. The characteristics of zeolites, which come from the structural confinement on the molecular dimensions, are crucial for shape-selective catalysis.

The catalytical acid sites at different positions of zeolites show a distinct confinement effect for reactant molecules, especially reflected in mordenite (MOR) zeolite catalyzing dimethyl ether (DME) carbonylation reaction.

Recently, a research team led by Prof. Liu Zhongmin from the Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) developed a new strategy to preferentially remove the acid sites in the 12-membered ring (12-MR) channels of MOR zeolite by a trimethylchlorosilane (TMCS) silylation treatment, which could improve the performance of DME carbonylation.

This study was published in ACS Catalysis on April 1.

Post link

‘Nano-reactor’ created for the production of hydrogen biofuel

Combining bacterial genes, virus shell creates a highly efficient, renewable material used in generating power from water

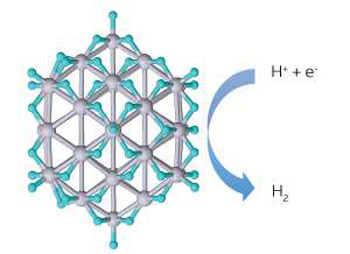

Scientists at Indiana University have created a highly efficient biomaterial that catalyzes the formation of hydrogen – one half of the “holy grail” of splitting H2O to make hydrogen and oxygen for fueling cheap and efficient cars that run on water.

A modified enzyme that gains strength from being protected within the protein shell – or “capsid” – of a bacterial virus, this new material is 150 times more efficient than the unaltered form of the enzyme.

The process of creating the material was recently reported in “Self-assembling biomolecular catalysts for hydrogen production” in the journalNature Chemistry.

“Essentially, we’ve taken a virus’s ability to self-assemble myriad genetic building blocks and incorporated a very fragile and sensitive enzyme with the remarkable property of taking in protons and spitting out hydrogen gas,” said Trevor Douglas, the Earl Blough Professor of Chemistry in the IU Bloomington College of Arts and Sciences’ Department of Chemistry, who led the study. “The end result is a virus-like particle that behaves the same as a highly sophisticated material that catalyzes the production of hydrogen.”

Post link

Eco-friendly composite catalyst and ultrasound removes pollutants from water

The research team of Dr. Jae-woo Choi and Dr. Kyung-won Jung of the Korea Institute of Science and Technology’s (KIST, president: Byung-gwon Lee) Water Cycle Research Center announced that it has developed a wastewater treatment process that uses a common agricultural byproduct to effectively remove pollutants and environmental hormones, which are known to be endocrine disruptors.

The sewage and wastewater that are inevitably produced at any industrial worksite often contain large quantities of pollutants and environmental hormones (endocrine disruptors). Because environmental hormones do not break down easily, they can have a significant negative effect on not only the environment but also the human body. To prevent this, a means of removing environmental hormones is required.

The performance of the catalyst that is currently being used to process sewage and wastewater drops significantly with time. Because high efficiency is difficult to achieve given the conditions, the biggest disadvantage of the existing process is the high cost involved. Furthermore, the research done thus far has mostly focused on the development of single-substance catalysts and the enhancement of their performance. Little research has been done on the development of eco-friendly nanocomposite catalysts that are capable of removing environmental hormones from sewage and wastewater.

The KIST research team, led by Dr. Jae-woo Choi and Dr. Kyung-won Jung, utilized biochar, which is eco-friendly and made from agricultural byproducts, to develop a wastewater treatment process that effectively removes pollutants and environmental hormones. The team used rice hulls, which are discarded during rice harvesting, to create a biochar** that is both eco-friendly and economical. The surface of the biochar was coated with nano-sized manganese dioxide to create a nanocomposite. The high efficiency and low cost of the biochar-nanocomposite catalyst is based on the combination of the advantages of the biochar and manganese dioxide.

A*STAR scientists have used first-principles computer simulations to explain why small platinum nanoparticles are less effective catalysts than larger ones.

Platinum nanoparticles are used in the catalysis of many reactions, including the important hydrogen evolution reaction used in fuel cells and for separating water into oxygen and hydrogen. Improved effectiveness of platinum nanoparticles to catalyze this reaction had been experimentally shown with decreasing nanoparticle size until it fell below about 3 nm. There was no clear explanation for why catalytic activity was reduced at this scale.

Post link

Catalysts are extremely important in variety of fields of industry, especially in energy sector. However, nowadays they are mostly made from platinum – one of the scarcest metals in the Earth’s crust. This means that production of them is rather expensive and difficult. But now scientists a…

A new fabrication technique that produces platinum hollow nanocages with ultra-thin walls could dramatically reduce the amount of the costly metal needed to provide catalytic activity in such applications as fuel cells. A transmission electron microscope image shows a typical sample of platinum…

MIT Scientists Overcome a Major Bottleneck in Carbon Dioxide Conversion

Study reveals why some attempts to convert the greenhouse gas into fuel have failed, and offers possible solutions.

If researchers could find a way to chemically convert carbon dioxide into fuels or other products, they might make a major dent in greenhouse gas emissions. But many such processes that have seemed promising in the lab haven’t performed as expected in scaled-up formats that would be suitable for use with a power plant or other emissions sources.

Now, researchers at MIT have identified, quantified, and modeled a major reason for poor performance in such conversion systems. The culprit turns out to be a local depletion of the carbon dioxide gas right next to the electrodes being used to catalyze the conversion. The problem can be alleviated, the team found, by simply pulsing the current off and on at specific intervals, allowing time for the gas to build back up to the needed levels next to the electrode.

Post link

How to look for a few good catalysts

Two key physical phenomena take place at the surfaces of materials: catalysis and wetting. A catalyst enhances the rate of chemical reactions; wetting refers to how liquids spread across a surface.

Now researchers at MIT and other institutions have found that these two processes, which had been considered unrelated, are in fact closely linked. The discovery could make it easier to find new catalysts for particular applications, among other potential benefits.

“What’s really exciting is that we’ve been able to connect atomic-level interactions of water and oxides on the surface to macroscopic measurements of wetting, whether a surface is hydrophobic or hydrophilic, and connect that directly with catalytic properties,” says Yang Shao-Horn, the W.M. Keck Professor of Energy at MIT and a senior author of a paper describing the findings in the Journal of Physical Chemistry C. The research focused on a class of oxides called perovskites that are of interest for applications such as gas sensing, water purification, batteries, and fuel cells.

Since determining a surface’s wettability is “trivially easy,” says senior author Kripa Varanasi, an associate professor of mechanical engineering, that determination can now be used to predict a material’s suitability as a catalyst. Since researchers tend to specialize in either wettability or catalysis, this produces a framework for researchers in both fields to work together to advance understanding, says Varanasi, whose research focuses primarily on wettability; Shao-Horn is an expert on catalytic reactions.

Post link

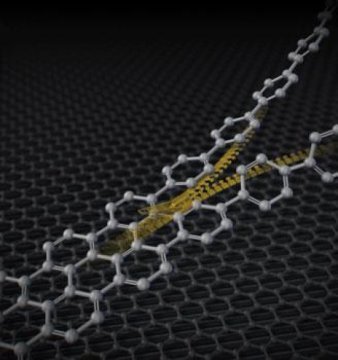

‘Zipping-up’ rings to make nanographenes

A fast and efficient method for graphene nanoribbon synthesis

Nanographenes are attracting wide interest from many researchers as a powerful candidate for the next generation of carbon materials due to their unique electric properties. Scientists at Nagoya University have now developed a fast way to form nanographenes in a controlled fashion. This simple and powerful method for nanographene synthesis could help generate a range of novel optoelectronic materials, such as organic electroluminescent displays and solar cells.

Nagoya, Japan – A group of chemists of the JST-ERATO Itami Molecular Nanocarbon Project and the Institute of Transformative Bio-Molecules (ITbM) of Nagoya University, and their colleagues have developed a simple and powerful method to synthesize nanographenes. This new approach, recently described in the journal Science, is expected to lead to significant progress in organic synthesis, materials science and catalytic chemistry.

Nanographenes, one-dimensional nanometer-wide strips of graphene, are molecules composed of benzene units. Nanographenes are attracting interest as a powerful candidate for next generation materials, including optoelectronic materials, due to their unique electric characteristics. These properties of nanographenes depend mainly on their width, length and edge structures. Thus, efficient methods to access structurally controlled nanographenes is highly desirable.

Post link

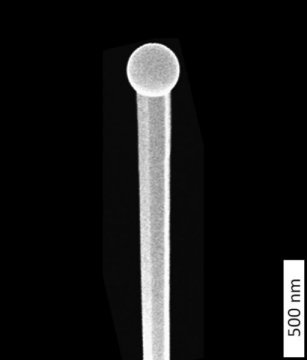

Scientists observe nanowires as they grow

X-ray experiments reveal exact details of self-catalyzed growth for the first time

At DESY’s X-ray source PETRA III, scientists have followed the growth of tiny wires of gallium arsenide live. Their observations reveal exact details of the growth process responsible for the evolving shape and crystal structure of the crystalline nanowires. The findings also provide new approaches to tailoring nanowires with desired properties for specific applications. The scientists, headed by Philipp Schroth of the University of Siegen and the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), present their findings in the journal Nano Letters. The semiconductor gallium arsenide (GaAs) is widely used, for instance in infrared remote controls, the high-frequency components of mobile phones and for converting electrical signals into light for fibre optical transmission, as well as in solar panels for deployment in spacecraft.

To fabricate the wires, the scientists employed a procedure known as the self-catalysed Vapour-Liquid-Solid (VLS) method, in which tiny droplets of liquid gallium are first deposited on a silicon crystal at a temperature of around 600 degrees Celsius. Beams of gallium atoms and arsenic molecules are then directed at the wafer, where they are adsorpted and dissolve in the gallium droplets. After some time, the crystalline nanowires begin to form below the droplets, whereby the droplets are gradually pushed upwards. In this process, the gallium droplets act as catalysts for the longitudinal growth of the wires. “Although this process is already quite well established, it has not been possible until now to specifically control the crystal structure of the nanowires produced by it. To achieve this, we first need to understand the details of how the wires grow,” emphasises co-author Ludwig Feigl from KIT.

Post link

Research uncovers mechanism behind water-splitting catalyst

Caltech researchers have made a discovery that they say could lead to the economically viable production of solar fuels in the next few years.

For years, solar-fuel research has focused on developing catalysts that can split water into hydrogen and oxygen using only sunlight. The resulting hydrogen fuel could be used to power motor vehicles, electrical plants, and fuel cells. Since the only thing produced by burning hydrogen is water, no carbon pollution is added to the atmosphere.

In 2014, researchers in the lab of Harry Gray, Caltech’s Arnold O. Beckman Professor of Chemistry, developed a water-splitting catalyst made of layers of nickel and iron. However, no one was entirely sure how it worked. Many researchers hypothesized that the nickel layers, and not the iron atoms, were responsible for the water-splitting ability of the catalyst (and others like it).

To find out for sure, Bryan Hunter (PhD ‘17), a former fellow at the Resnick Institute, and his colleagues in Gray’s lab created an experimental setup that starved the catalyst of water. “When you take away some of the water, the reaction slows down, and you are able to take a picture of what’s happening during the reaction,” he says.

Post link

Infrared lasers reveal unprecedented details in surface scattering of methane

When molecules interact with solid surfaces, a whole range of dynamic processes can take place. These are of enormous interest in the context of catalytic reactions, e.g. the conversion of natural gas into hydrogen that can then be used to generate clean electricity.

Specifically, the interaction of methanemolecules with catalyst surface such as nickel is of interest if we are to gain a detailed and meaningful understanding of the process on a molecular level. But studying scattering dynamics of polyatomic molecules such as methane has been challenging because current detection techniques are unable to resolve all the quantum states of the scattered molecules.

The lab of Rainer Beck at EPFL has now used novel infrared laser techniques to study methane scattering on a nickel surface for the first time with full quantum-state resolution. Quantum-state resolved techniques have contributed much to our understanding of surface-scattering dynamics, but the innovation here was that the EPFL team was able to extend such studies to methane by combining infrared lasers with a cryogenic bolometer: a highly sensitive heat detector cooled to 1.8 K that can pick up the kinetic and internal energy of the incoming methane molecules.

Post link

From greenhouse gases to plastics: New catalyst for recycling carbon dioxide discovered

Imagine if we could take CO2, that most notorious of greenhouse gases, and convert it into something useful. Something like plastic, for example. The positive effects could be dramatic, both diverting CO2 from the atmosphere and reducing the need for fossil fuels to make products.

A group of researchers, led by the University of Toronto Ted Sargent group, just published results that bring this possibility a lot closer.

Using the Canadian Light Source and a new technique exclusive to the facility, they were able to pinpoint the conditions that convert CO2 to ethylene most efficiently. Ethylene, in turn, is used to make polyethylene—the most common plastic used today—whose annual global production is around 80 million tonnes.

“This experiment could not have been performed anywhere else in the world, and we are thrilled with the results” says U of T Ph.D. student Phil De Luna, the lead researcher on this project.

Post link

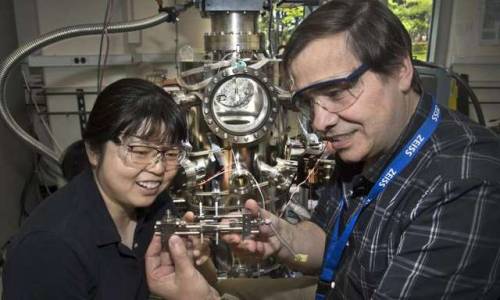

New efficient, low-temperature catalyst for hydrogen production

Scientists have developed a new low-temperature catalyst for producing high-purity hydrogen gas while simultaneously using up carbon monoxide (CO). The discovery-described in a paper set to publish online in the journal Science on Thursday, June 22, 2017-could improve the performance of fuel cells that run on hydrogen fuel but can be poisoned by CO.

“Thiscatalyst produces a purer form of hydrogen to feed into the fuel cell,” said José Rodriguez, a chemist at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory. Rodriguez and colleagues in Brookhaven’s Chemistry Division-Ping Liu and Wenqian Xu-were among the team of scientists who helped to characterize the structural and mechanistic details of the catalyst, which was synthesized and tested by collaborators at Peking University in an effort led by Chemistry Professor Ding Ma.

Because the catalyst operates at low temperature and low pressure to convert water (H2O) and carbon monoxide (CO) to hydrogen gas (H2) and carbon dioxide (CO2), it could also lower the cost of running this so-called “water gas shift” reaction.

“With low temperature and pressure, the energy consumption will be lower and the experimental setup will be less expensive and easier to use in small settings, like fuel cells for cars,” Rodriguez said.

Post link

Aluminum “Octopods” – Shape Matters for Light-Activated Nanocatalysts

Study: Pointed tips on aluminum ‘octopods’ increase catalytic reactivity.

Points matter when designing nanoparticles that drive important chemical reactions using the power of light.

Researchers at Rice University’s Laboratory for Nanophotonics (LANP) have long known that a nanoparticle’s shape affects how it interacts with light, and their latest study shows how shape affects a particle’s ability to use light to catalyze important chemical reactions.

In a comparative study, LANP graduate students Lin Yuan and Minhan Lou and their colleagues studied aluminum nanoparticles with identical optical properties but different shapes. The most rounded had 14 sides and 24 blunt points. Another was cube-shaped, with six sides and eight 90-degree corners. The third, which the team dubbed “octopod,” also had six sides, but each of its eight corners ended in a pointed tip.

Post link